In this term’s Digital Cultures course, we studied the interrelationships between society, culture, and digital technologies, exploring their nexus today and in the futures.

The beginning of the course set the context on designing in a polycrisis. From a western perspective, polycrises are difficult to understand as they require people to go beyond a national perspective towards a planetary scale. Our dominant economic model pushes extractivism in search of endless economic growth, running on fossil fuels, mining, and cheap labor. Optimistic attempts to use design to change oppressive systems do not go far enough. Human-centered design, for example, emphasizes that everything must be useful, comfortable, efficient, consumable, abstracting humans to workers and consumers. In this context, artificial intelligence has been developed as a tool that uses algorithm-based technologies to solve complex tasks that previously required human thinking. It does so with varying levels of autonomy and assigns risks and works to minimize them. But because it runs on the inputs and values of society today, even the most “objective” AI tool has bias.

This context matters because the impacts of digital cultures extend beyond the digital realm. We studied the materiality of digital cultures, an aspect that is often overlooked because “the digital” seemingly occupies no physical space. Critical data center studies offer a framework for understanding the material supply chain behind big data, the water demands, the labor that is required and the conditions and compensation of this labor, the energy consumption, and the resulting heat and waste that is produced.

Technology is not only changing the landscape, but also our perceptions on time. Gustavo Nogueira visited IAAC to give a guest lecture, sharing how temporal changes happen from different perspectives. For users, technical acceleration, exemplified by instantaneous responses and real-time updates, has accelerated social change, and this in turn has accelerated the pace of life. It is easy to feel trapped in this self-perpetuating cycle of acceleration, and even feel stuck in the past as deterministic outdated data reinforces outdated norms and bias. Disentangling ourselves from this phenomenon involves responding to it in new ways: slowing down. Nogueira proposed different frameworks for understanding time and our place within it, from thinking of time as a torus with the past and present constantly producing various futures, to the Bakongo cosmogram, thinking about time in a cyclical manner, mapping it onto the parts of the day.

By examining meanings, metaphors, algorithms, and power, we began to uncover different myths about technologies that can cloud thinking about alternatives. One particularly potent example was the different metaphors ascribed to data, explored in “Data is the New ‘_’” by Sara M. Watson. Data can be thought of a resource or byproduct, described as raw or cleansed. What would it mean to think of data as a mirror, as a practice, a footprint or shadow of ourselves? Could reshaping different metaphors about technology better equip society to protect our data and design our systems?

But we did not stop at examining how we think about technology. Technology is also shaping what we we think. An exploration of the realities of digital cultures revealed how misinformation and ideas of truth are shifting within digital media. In some ways, humans are living in an augmented reality, where digital layers are superimposed over our direct environments, reshaping our cumulative perceptions. Though this could lead to a symbiosis of digital and analog realities, it has made way for misinformation and given rise to conspiracies, as media literacy lags to keep pace with the changing media landscape. These come at a cost, making collaborative efforts like responding to the pandemic and resolving climate change harder to accomplish.

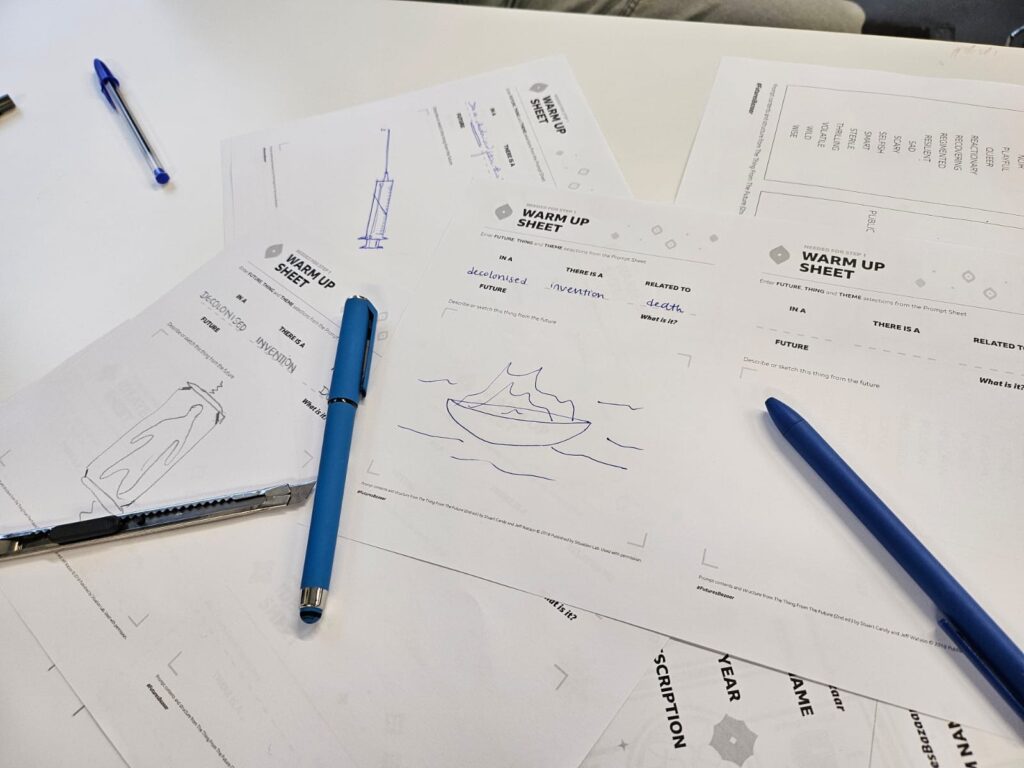

One way to leverage meaning to shape understanding and foster imagination is through critical design. Critical design uses fiction and speculative design proposals to challenge assumptions and conceptions about the role objects play in everyday life. It is product design that is not focused on commercial outcomes of physical utility, rather to inspire debate or increase awareness. The class culminated in a design fiction, where designers create tangible and provocative prototypes from possible futures to help discover the consequences of decision-making today.

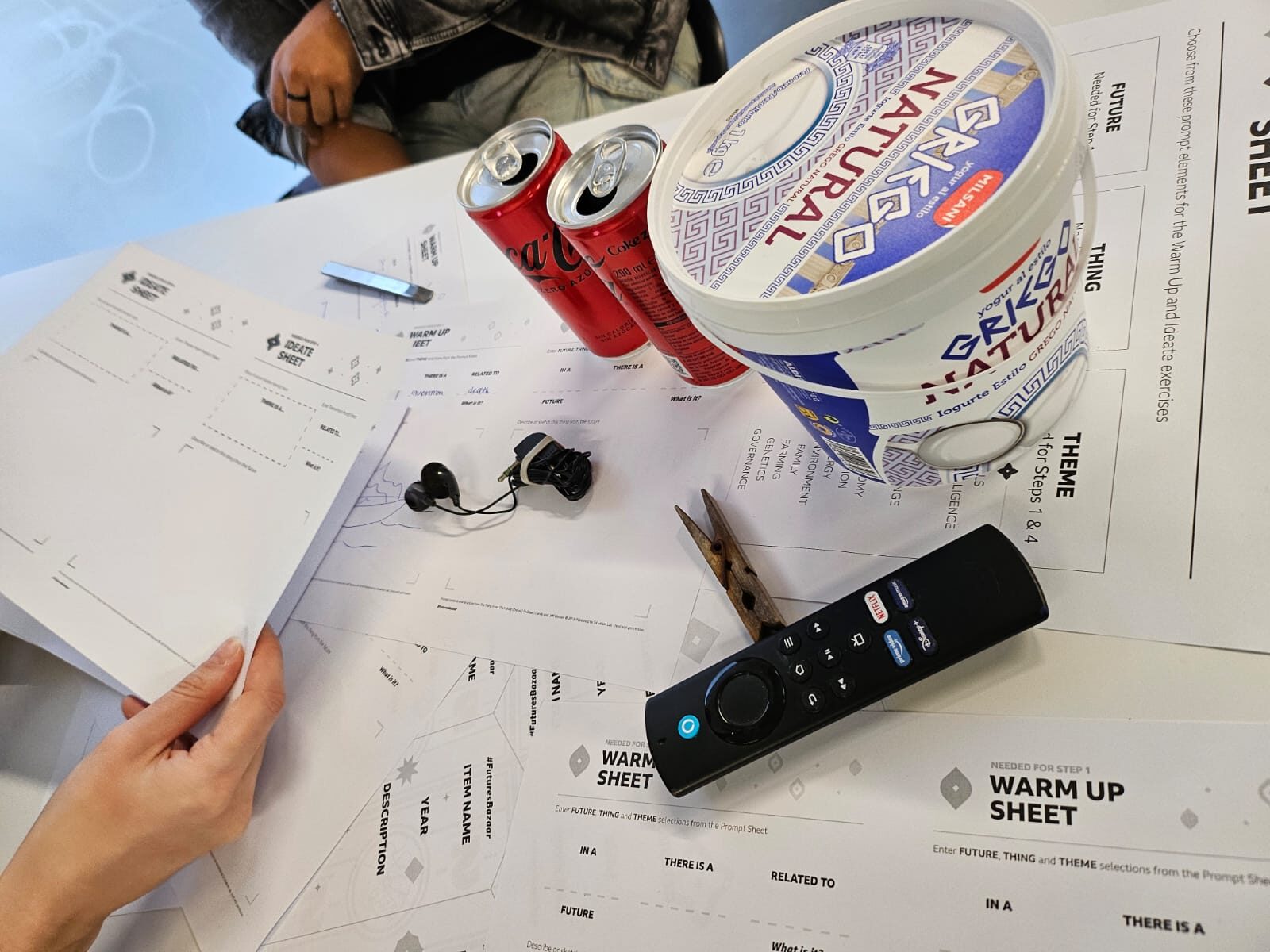

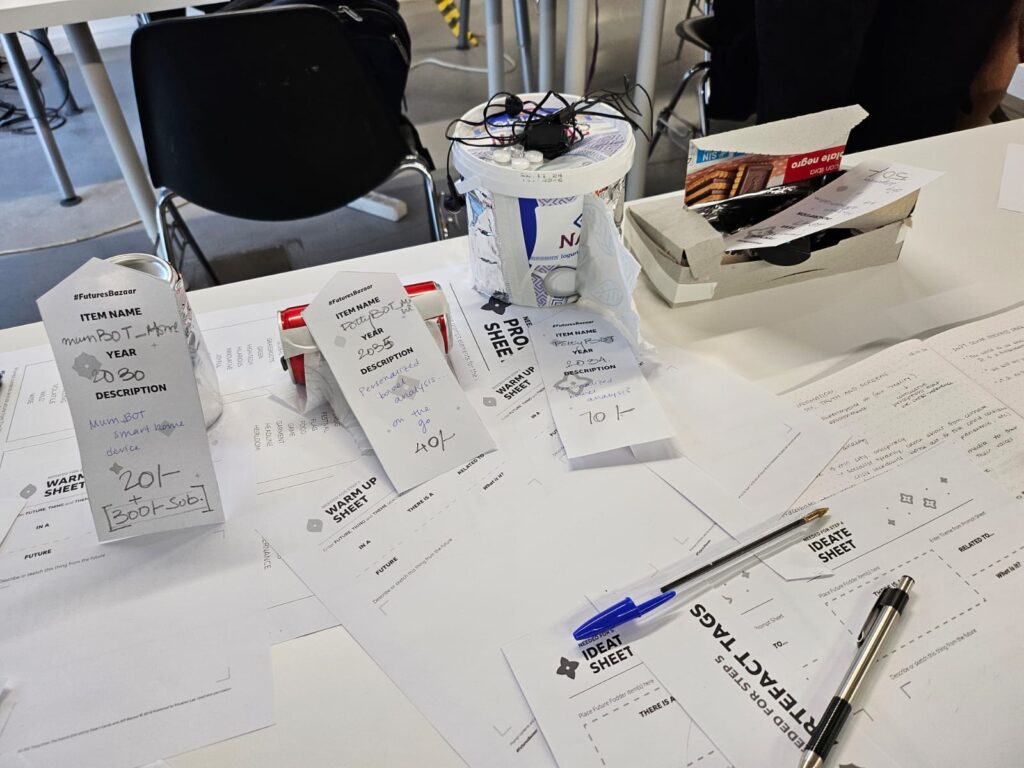

In our Bizarre Bazaar, we worked in groups to tell stories about possible futures. My group chose to focus on the futures of data privacy, authentication, and e-commerce. To set a foundation, my group created a proto-video telling the story about a woman who moved to Mumbai and signed up for a virtual assistant to help balance her busy schedule. Though helpful, the assistant, mumBOT, required intrusive amounts of data and access to social media, communication, and commercial accounts. This story followed the woman as she relied increasingly on mumBOT to maintain her friendships and run her household, until her information was stolen in a data breach. With this story as our context, my group collectively imagined different ways technology can be increasingly intrusive while offering increasingly helpful services.

We worked with household materials that were heading to the landfill and developed prototypes for imaginary products from this future. Among those we created were the Potty Bot, a machine that conducts an analysis of a person’s digestive health, the Know Me, a authentication tool that produces a chip that can be implanted on a person to avoid pesky OTM authentication or repeated biometric readings, and the mumBOT Home, a smart-home speaker for the mumBOT to better manage domestic spaces.

The Bizarre Bazaar offered an opportunity to imagine, craft, and play, finally ending in each of us taking on seller and shopper roles and purchasing future products made by classmates. The exercise gave us freedom to use our imagination, be resourceful, and think of criticism as something that can be fun or even funny. Ultimately, I came away from the digital cultures class with a more expansive view of the implications of digital technologies and with a new set of strategies and practices to adopt when examining futures and designing for them.