New economic models offer opportunities to create just, sustainable, and vibrant systems in the face of climate crises, social inequality, and profit-seeking cultures. Over the course of the Emerging Economies series, various experts shared novel frameworks for exchanging goods and knowledge, how these can and have been implemented, and their impacts.

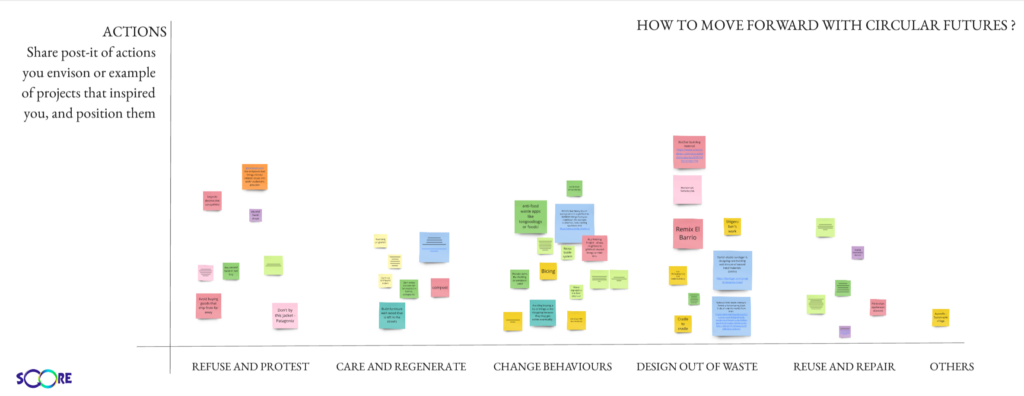

Marion Real spoke with the course to explain how circular economies can be created and maintained. Circular economies are those where economic outputs are recycled as future inputs. Beyond changes in production, these require changes in society in order to scale, for example to slow down consumption. Different strategies that can set the foundation for a successful circular economy include change in behaviors, repairing damaged products, design out of waste, and actively calling for policy change.

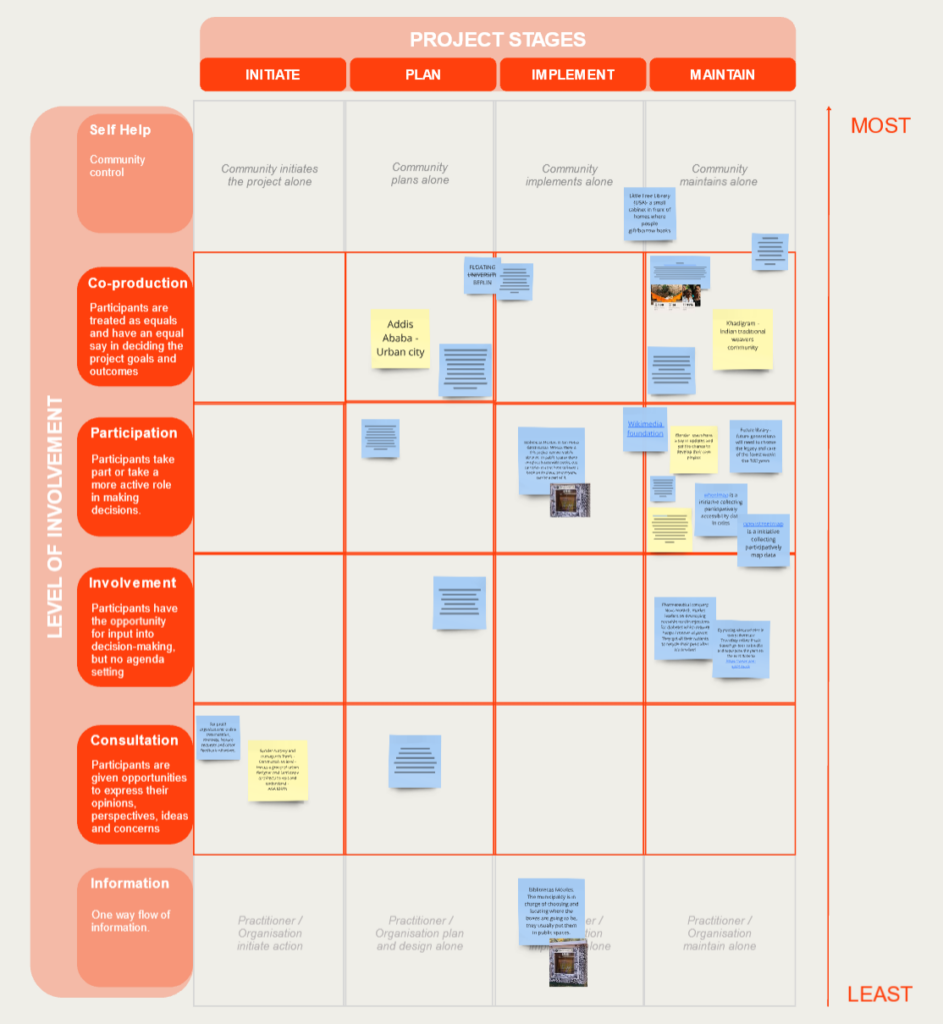

Jessica Guy introduced the ideas of distributed economies and mass collaboration, which go beyond spatial distribution towards distributing control and value more equitably across communities or networks. This framework pushes for open access to knowledge, one memorable idea being that they prioritize “free software as in ‘free speech,’ not ‘free beer.'” Having full access to tools is crucial, as being able to understand how something works and how to fix it is critical to truly having agency over a tool. As designers, it is crucial to evaluate how we engage with end users and examine to build collective responsibility. At the systemic scale, decentralized economies, democratized resources, and large-scale collaboration can be used to define an alternative to current economic systems.

Alessandra Schmidt discussed social entrepreneurship and impact economies, in which social and ecological outcomes are prioritized over profit-maximization. Social entrepreneurship considers negative externalities and considers new modes of business that emphasize broader social impacts. Within this model, solidarity economies emerge with a focus on social justice and community resilience. In this way, the private sector, particularly social impact enterprises, can have a role in driving urban change.

Case studies of regenerative economies and social sustainability projects were introduced by Milena Juarez. These centered on the DIDO (data-in-data-out) model, in which local production is prioritized and only knowledge is exchanged. Fab Cities contribute to regenerative economies as they focus on DIDO frameworks. Other projects mentioned included CENTRINNO, a reclamation of industrial heritage and push towards a DIDO system, and urban mining analysis as a way to recover materials from defunct buildings. In shifting towards a regenerative economy, Juarez argued how designers and makers can play a key role through their skills and perspectives in fostering equity and empowering residents in cities.

Shifting towards an nature-based approach, Jonathan Minchin presented on ecological interactions and the economies of nature. Current technologies give us new methods to retrieve and analyze the natural world, identifying patterns and signals that before were hidden before. This new layer of data can help us optimize our dependency on natural outputs, allowing us to better design based on the needs of the situation to avoid over-extraction/overproduction. This kind of framework complicates the idea of economies of scale and allows us to work towards economies of local scale or appropriate technology, customizing material needs to local environments. Finally, while designing for local conditions will produce more ecologically viable outcomes, self-sufficiency does not imply isolation. Because an ecology cannot be isolated, the impacts of this shift will stretch cross regions.

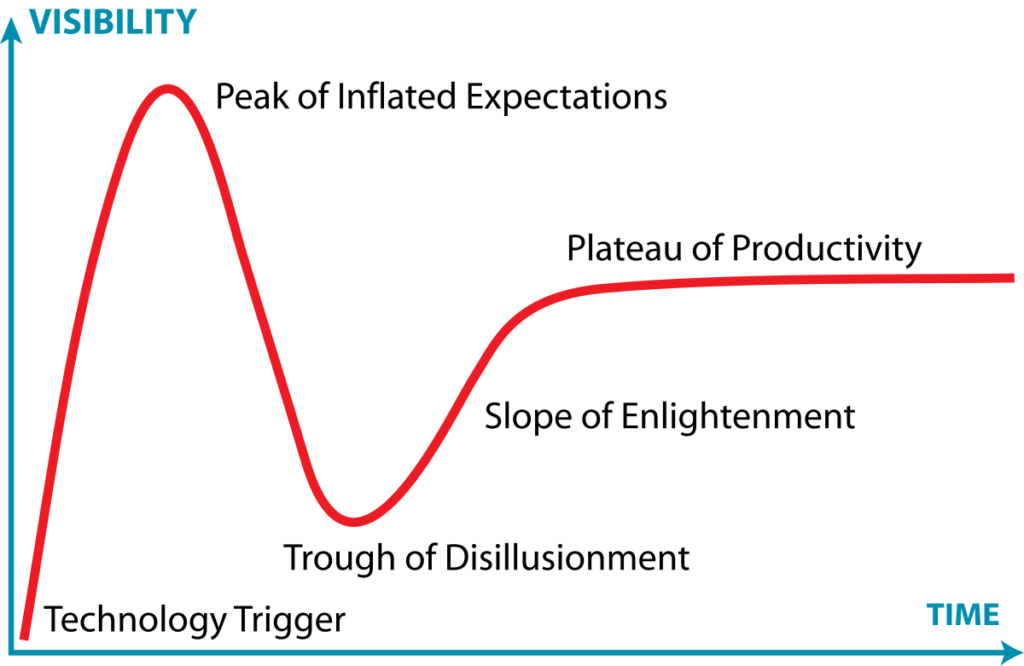

Albert Cañigueral closed the course with a discussion on the future of work as we see an increase in the capacities and usage of artificial intelligence. While AI offers the opportunity to reduce the physical effort or menial summarizing/transcription tasks, many jobs more workers fear the eventual obsolescence of their jobs by AI. Indeed, AI has an interesting paradox that the more one uses it, the more the machine extracts your own knowledge/skills as it is constantly learning, a process called reinforced learning from human feedback (RLHF). Despite these fears, the promises of AI can be extremely deceptive. Already, rushed AI implementation has lead to costly mistakes.

As seen through the Gartner Hype Cycle diagram, sometimes, emerging technologies often undergo inflated expectations before facing disillusionment, and eventually reaching a middle ground of productivity after more of the public better understands the technology. In this way, AI might now be reaching its trough of disillusionment, but that does not mean that there aren’t productive ways to leverage it. According to Ethan Mollick, four rules to guide AI engagement are:

- Always invite AI to the table

- Be the human in the loop

- Treat AI like a person (but tell it what kind of person it is)

- Assume it’s the worst AI you will ever use

Using these rules, AI can be an effective tool (and we start shifting away from viewing it as a subject). Responsible and considered AI use can offer us the opportunity to rethink our business processes, much like many of the other frameworks discussed over the course of the term. These models and strategies provide a powerful toolkit to make our inputs appropriate, make our processes fair, and produce value at the local and global scale beyond the traditional “products in, trash out” models.