“The vernacular has always embodied a kind of instinctive ecological intelligence — evolving over time with a sensitivity to resources, energy, and context.” – Dr. Ahmet Eyüce

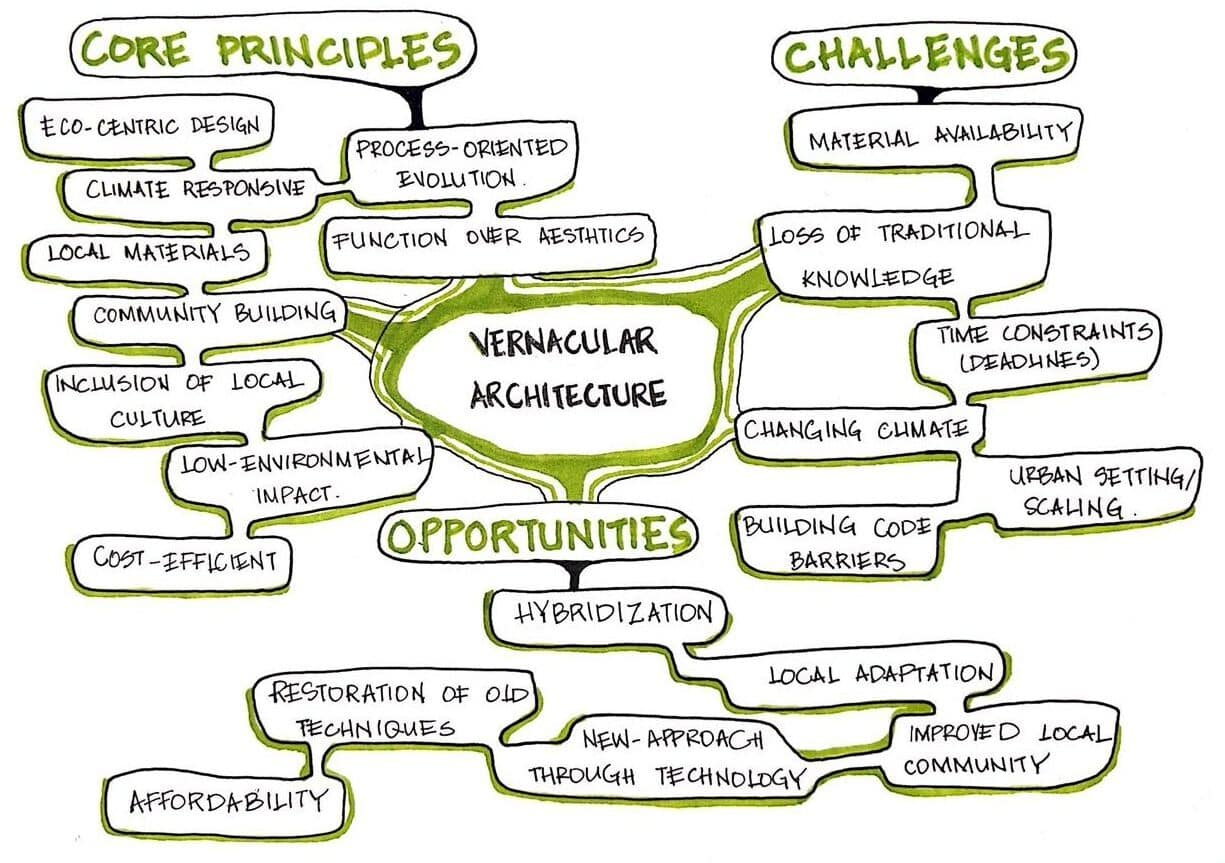

As architecture continues to scale upward, streamline processes, and globalize its language, I find myself drawn to the quiet wisdom of vernacular architecture — the kind that emerges from the land, the climate, the people. It is in many ways the foundation for many architectural forms that are followed currently. Many principles that we now talk about about in sustainable and ecological design such as passive strategies, climate responsive, material efficiency were all deeply rooted in vernacular traditions long before these concepts became part of current architectural theory today.

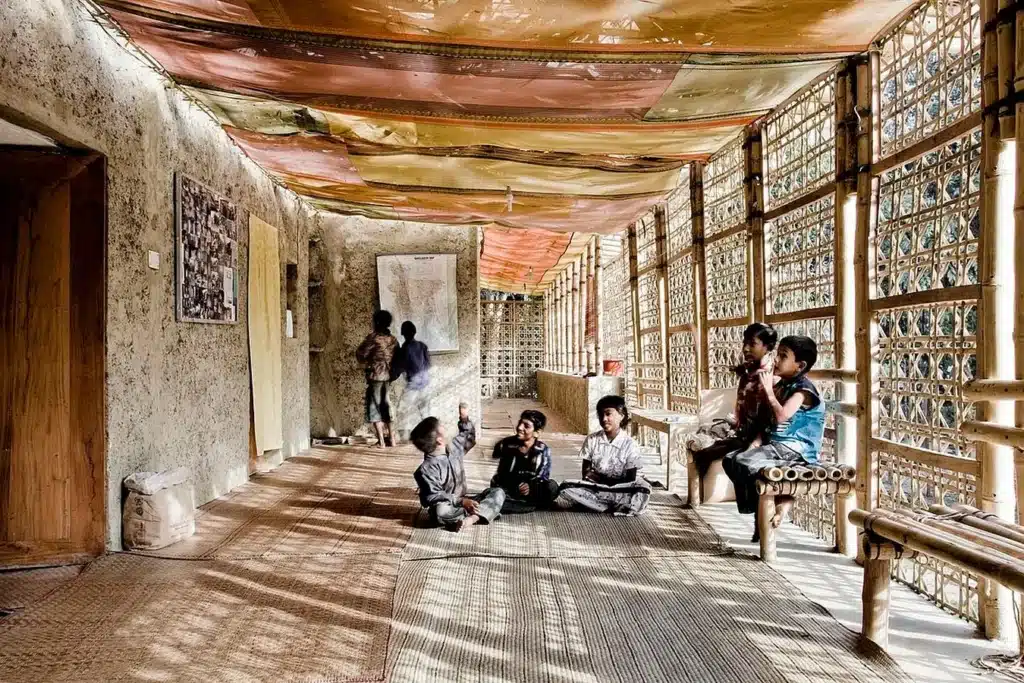

What resonated most deeply was the way these architectural forms are not the work of individual designers, but the accumulated knowledge of entire communities, passed through generations — a form of architectural “common sense” that modern systems often ignore in favor of novelty or speed. We speak of climate-responsive architecture today, yet vernacular builders instinctively knew how to orient a home for shade and breeze, how to choose materials that breathe, and how to build with the land rather than against it. Eyüce also emphasizes on process-oriented thinking that it is not only the final built form that matters, but the slow, collective evolution behind it — shaped by trial, error, and continuous adaptation.

I found myself drawn to the quiet contrast of the simplicity of form and the complexity of reasoning behind these structures. They may appear humble, but they hold powerful lessons on efficiency, longevity, and environmental awareness. They invite us to slow down, to listen — not just to users, but to materials, climate, and place. I also reflected on the disconnect between tradition and modernity with barriers to integrating vernacular logic into modern urban design: regulations, economic systems, and the loss of craft and the dominance of industrialized aesthetics. But instead of a limitation, this gap can be seen as a design opportunity.

In relation to other areas like Adaptation and Mitigation, vernacular architecture very well aligns to their principles. Vernacular buildings were shaped in direct response to the local climate and environment and have been adapting to the challenges through time of design. Hence, these design strategies can allow communities to adapt to environmental conditions long before for the need of mitigation measures.

In conclusion I would say vernacular architecture isn’t just about the past — it’s a path forward. A rooted, conscious progress that reminds us we can still build in ways that truly belong to their surroundings- relearning how to build like we belong.