The Power of Community-Built Cities: Looking into a Bottom Up Approach

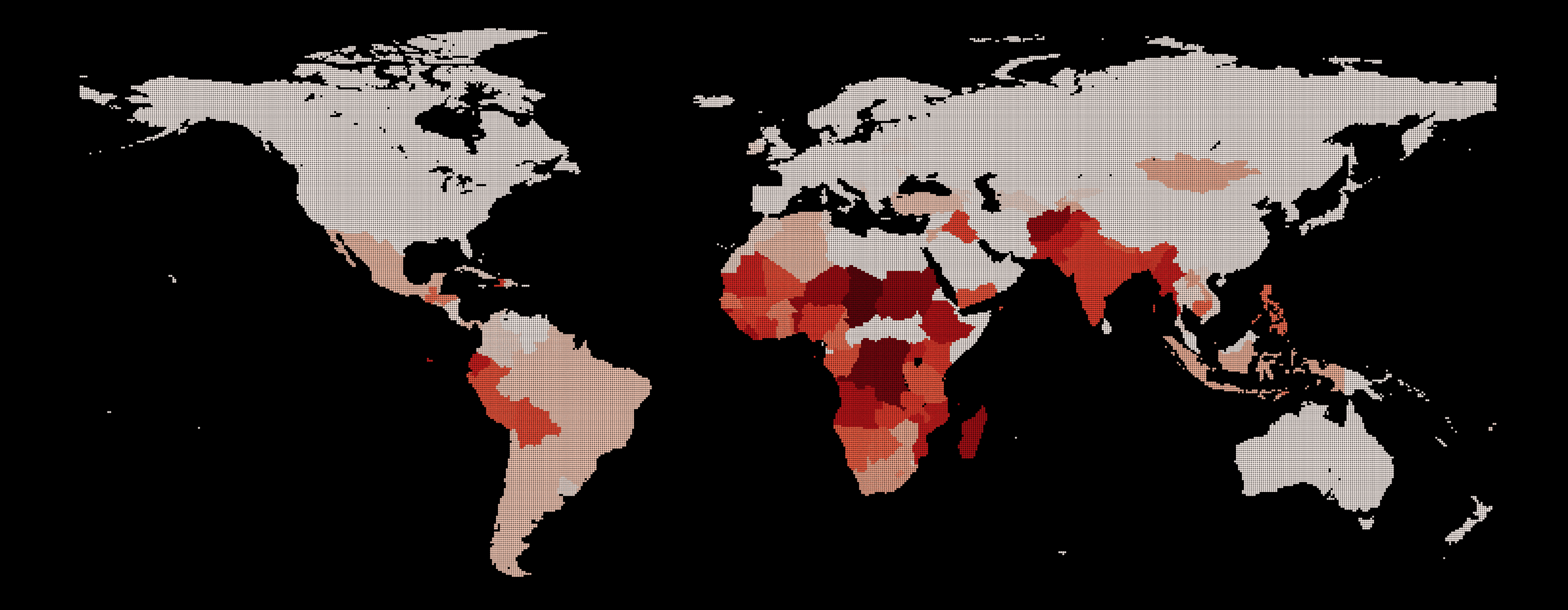

Over 1.1 billion people live in what are often labeled as ‘informal settlements.’ Despite the vast scale and human impact of this issue, these communities remain largely overlooked in policy and investment decisions. This neglect may stem, in part, from the terminology itself: labels like ‘slum’ or ‘informal’ can obscure the complexity, resilience, and legitimacy of these urban spaces, reinforcing their marginalization.

The Weight of a Word: “Informal”

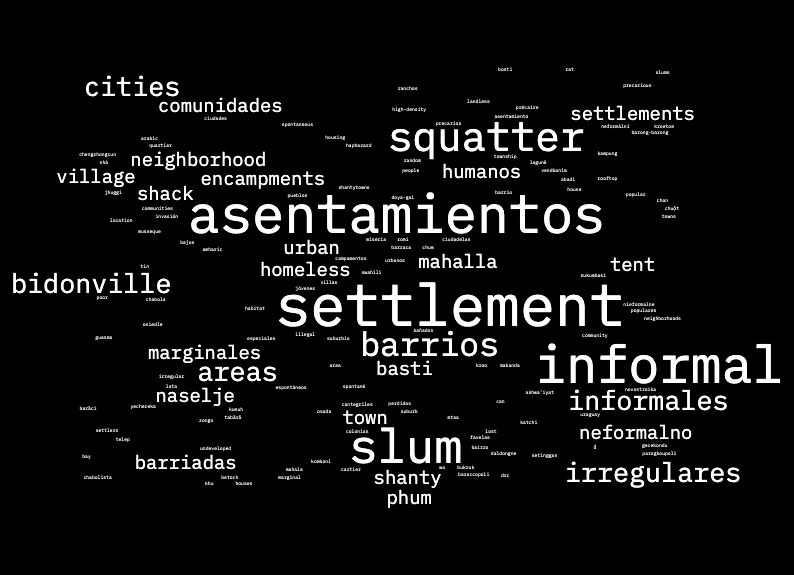

Names like slum, shantytown, bidonville, or favelas are more than just descriptive terms for informal housing, they are deeply loaded with social, political, and historical meanings. The word cloud visually demonstrates how a wide range of labels are used across different regions, languages, and cultural contexts. While these terms may arise from local vernaculars (asentamientos, colonias, barrios marginales, basti, etc.), their use in media, academia, and policy often reinforces a division between “formal” and “informal,” “modern” and “backward,” “clean” and “dirty,” “legal” and “illegal.”

These naming conventions contribute to a process of othering, where communities are framed as outside the norm or undeserving of the same rights and resources. For example, in Chile, the distinction between Campamentos and Tomas reflects not only the technical status of the land occupation but also influences how these communities are treated by authorities and perceived by the public. Campamentos may receive some recognition and eventual support, while Tomas are often criminalized, reinforcing stigmas and marginalization.

What is “Informal?”

Land Tenure

In most cases, informal settlement dwellers do not have ownwership over their land.

Adequate Infrastructure

Informal areas often lack basic services such as clean water, sanitation, electricity, and waste management and form without the help of public planning.

Compliance with Regulations

Informal housing is often built without regulatory measures from local government due to its self made formation.

Public Services

Access or lack thereof public services is one aspect that separates formal from informal settlements.

Stories of Self-made Cities

Case Studies of Notable Informal Settlements

Neza | Mexico City, Mexico

Neza began developing in the 1940s and 1950s on the dry bed of Lake Texcoco, as migrants from across Mexico settled the area in search of affordable land and opportunity. Initially built without formal infrastructure, it grew rapidly through self-constructed housing and informal urbanization. Today, it is home to over 1.1 million people, having transformed from one of Latin America’s largest slums into a fully urbanized municipality on the edge of Mexico City.

Housing

Residents constructed their own homes, often starting with temporary materials and gradually upgrading them into permanent structures through incremental building.

Community Planning

Power and road paving came after years of collective mobilization and negotiation with government bodies, a classic example of “urban citizenship in action.”

Water & Sanitation

Communities organized to bring in water trucks, dig makeshift drains, and eventually lobby for state investment in piped water and sewerage.

Education & Healthcare

Over time, Neza gained public schools, clinics, and cultural centers, many championed by resident committees and neighborhood associations.

Most Notable Achievement: Political Power

An influential site for the mass politics movement from residents starting with their payment strike in 1969. Perhaps one of their biggest achievements came in the 1980s–90s, Neza residents began winning local elections, giving them direct control over urban planning and budgeting, transforming it into a fully incorporated, functioning city.

Dharavi | Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Dharavi began developing in the late 1800s during British colonial rule, initially as a fishing village that expanded with waves of internal migrants. Today, it is home to an estimated 700,000 to over 1 million people, making it one of the most densely populated areas in the world.

Housing

Most structures are self-built, often upgraded over time from temporary shelters to permanent, multi-story homes, a form of incremental architecture.

Community Planning

Groups like SPARC and the NSDF have partnered with residents to conduct surveys, mapping, and upgrading projects that feed into policy discussions and planning.

Water & Sanitation

Residents and local organizations have led small-scale drainage improvements where government systems were absent.

Education & Healthcare

Local NGOs have established schools, clinics, and community centers, creating access where formal services were limited.

Most Notable Achievement: Economic Infrastructure

Dharavi hosts an estimated 20,000+ informal businesses, from leather goods to pottery, contributing over $1 billion annually to Mumbai’s economy. This economic engine grew without formal recognition or infrastructure, proving the capacity of informal settlements to generate wealth, employment, and services at scale. Despite these exports, most residents still live in poverty as the wages they earn on these goods are low.

Rio de Janiero, Brazil

Rocinha began forming in the early 20th century, when rural migrants from Brazil’s northeast settled on the steep hillsides of Rio de Janeiro in search of work and opportunity. Initially informal and self-built, the community grew rapidly alongside the city’s urban expansion. Today, Rocinha is home to an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 residents, making it one of the largest and most well-known favelas in Brazil and a success story in developing infrastructure in a favela.

Housing

Housing infrastructure has been built incrementally by residents themselves, transforming informal, self-constructed homes over time into multi-story brick buildings through collective labor, local knowledge, and community adaptation.

Community Planning: Sankofa Museum of Rocinha

The Sankofa Museum is a community-led initiative in Rocinha that reclaims the area’s deeper history, highlighting its Indigenous Tamoio roots and challenging dominant narratives about the city. By reframing the favela’s origin story, the organization exposes historical injustices while celebrating the creativity, resilience, and power of its residents. Through counter-narratives and alternative learning practices, Sankofa fosters a deeper understanding of community-led transformation and resistance.

Water & Sanitation: Rocinha without Borders

a community-led platform that fosters inclusive dialogue between residents, authorities, and external stakeholders. Through regular meetings and active engagement, it has built a strong network of urban thinkers rooted in the favela. One key success was mobilizing against a proposed cable car project, which residents argued would cause unnecessary evictions and shift focus away from essential services like water, sanitation, and hygiene.

Education & Healthcare

Education and healthcare in Rocinha exist through a fragile blend of state provision, community action, and non-profit support, with residents continually filling the gaps left by public systems through solidarity and grassroots solutions.

Most Notable Achievement: Community Activism

Rocinha has a long and vibrant history of activism, rooted in community resistance, cultural pride, and the fight for basic rights. Residents have consistently organized to demand infrastructure, challenge harmful urban policies, and assert their place within the city. From grassroots health initiatives to urban planning debates, Rocinha has become a symbol of collective action and the power of self-determination in Brazil’s urban landscape.

Orangi Town | Karachi, Pakistan

Orangi Town began taking shape in the 1960s as a peripheral settlement for low-income migrants arriving in Karachi, particularly after the partition of British India and the later influx following the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. Lacking formal urban planning or state support, residents built the area themselves over time. Today, Orangi is home to an estimated 2.4 million people, making it one of the largest informal settlements in the world.

Success in low cost infrastructure: Orangi Pilot Project

Since the 1980s, residents built over 8,000+ small-scale sewerage systems, covering more than 15,000 lanes.

One of the most notable achievements is the community-led sanitation system. This was done with minimal government support and often funded by residents themselves

Beyond “Informal”

The comparison between informal and formal settlements should extend beyond conventional metrics such as land area, population density, building infrastructure, and access to water and electricity. A comprehensive assessment must also consider indicators of healthy living, including neighborhood connectivity, levels of environmental pollution, carbon emissions, and the quantity and management of both consumed resources and generated waste. Such an integrated approach enables a more nuanced understanding of urban inequality and sustainability across different settlement typologies.

Factors to study further before naming any settlement:

- Carbon emission

- Waste produced

- Neighborhood connectivity

- Social and mental health factor

- Pollution

Naming is Power

Despite all of these infrastructure updates needed for formality are all of these communities still considered ‘informal,’ or ‘slums’. Infrastructure updates are not all that communities need, they need support and recognition to make larger changes.

“State power is reproduced through the capacity to construct and reconstruct categories of legitimacy and illegitimacy”

p.149 Ananya Roy, Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning. Journal of the American Planning Association

As urbanist Ananya Roy reminds us, “State power is reproduced through the capacity to construct and reconstruct categories of legitimacy and illegitimacy.” The words we use, slum, informal, illegal, don’t just describe. They authorize or exclude, often without ever acknowledging the people behind the place. When we label entire neighborhoods as “informal,” we are not just identifying their planning status, we are signaling their position in a hierarchy of value, access, and rights.

What if we flipped the script? What if we recognized these communities not by what they lack, but by what they build?