Behind the scenes

We began our story-making process using another research project as a jumping-off point. In another course, we explored the detection and analysis of informal settlements in Northern Chile through satellite imagery. We wanted to invert our perspective and work with the topic of informality from the perspective of experiencing life in camps and navigating the formal and informal first-hand.

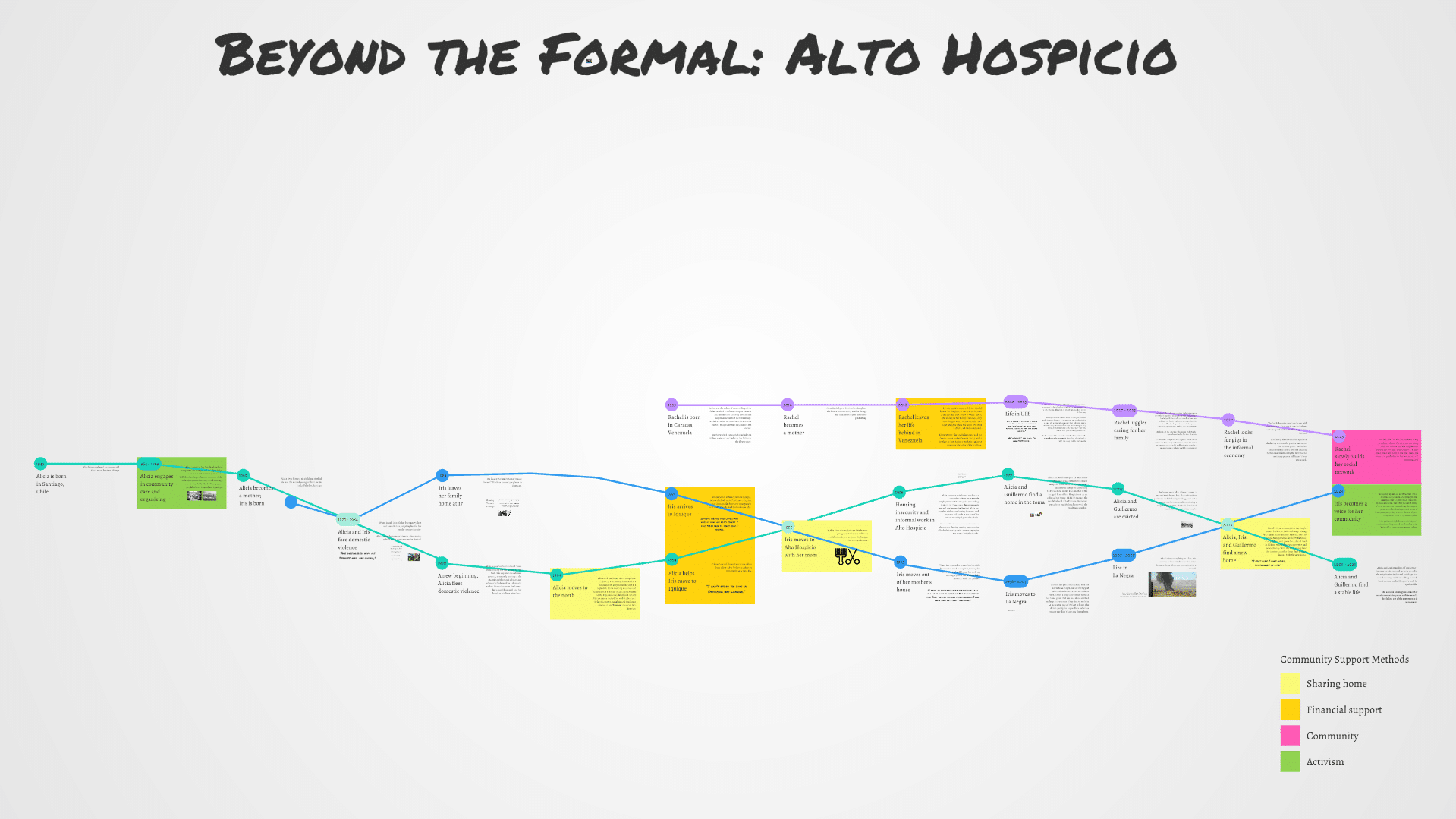

We grounded our work in two documents that talked about personal experiences in the campamentos of Alto Hospicio. Three stories were taken from interviews conducted by Alfredo Rodríguez and Paula Rodríguez Matta in 2023, and used key moments in the story as opportunities to add background on structural issues that cause these conditions. These three individuals highlight periods of struggle and triumph throughout their life journeys, but in various points come together as a community.

We then researched on the history of Chilean social housing and housing deficit. We based our knowledge on two papers, created a timeline of it, to then create links between the three personas and the coutry’s history.

Based on the stories, we set out to highlight the varying strategies camp residents employed to build communities, find stable living conditions, and work towards dignified housing. Chile’s infamous adoption of neoliberal policies during the Pinochet regime had long-lasting impacts on the country, and it was interesting structural environment from which to compare these forms of grassroots resistance.

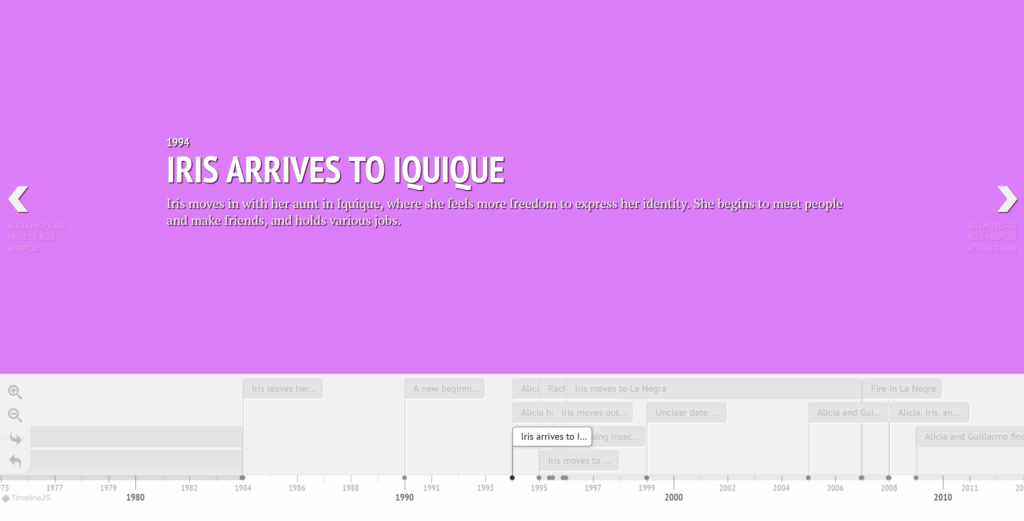

Originally, we began to form our narrative as a timeline, telling the chronological paths of each of the women. We soon found that timelines didn’t adequately represent the important moments of connections between the women, and it wasn’t easy to understand the broader picture or commonalities among the different narratives. We then decided to switch to using the timeline as a form of structuring the personal narratives but jumping in and out and subverting chronological storytelling to dynamically tell the stories of these three women and the story of inhabiting informal settlements as an inherently political act. By adding in details on policies and rights that created the conditions in the stories, we create the comparison between the structural decisions that communities must overcome in their search for dignified housing.

We decided it would be best to switch tools, so we chose Prezi because it allowed us to create a timeline with time jumps, better aligning with the narrative we wanted to convey. We started with rough drafts ni Miro outlining how we envisioned the storyline unfolding, and from there, we developed the final version.

The story

This story includes both positive and negative events. On the negative side, we see instances of discrimination, evictions, scams, and a government that neglects its people. On the positive side, the community overcomes these challenges through mutual support, such as sharing housing, offering financial help, fostering a sense of community, and engaging in activism.

Community Support Methods

Sharing a home

Financial support

Community

Activism

Systemic Challenges

Abandoning Government

Scams

Discrimination

Opression

Since the 19th century, Chile has transitioned from a predominantly rural society to an urbanized one, reaching nearly 90% urbanization by the 2002 Census. This process has been accompanied by a long and difficult history of housing policies attempting to address the growing demand from an increasingly urban population.

From early efforts such as the 1906 Law on Workers’ Housing, inspired by European models, to the later establishment of public institutions aimed at financing and regulating housing, the state’s role has evolved. Yet, throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, the most vulnerable sectors have consistently been overlooked.

The failure to meet housing needs can be traced to a combination of underfunded public initiatives, overreliance on the private sector through insufficient incentives, and a neoliberal framework that gained dominance during the military dictatorship. This model shifted responsibility to individuals through savings requirements, provided one-time subsidies without structural support, and neglected integrated urban planning. Even efforts in democratic periods often maintained the same framework, prioritizing quantity over quality and cost-efficiency over livability.

Despite various reforms, these approaches have never fully addressed the housing crisis in all its complexity, and to this day, thousands of Chileans remain without access to dignified, secure, and well-located homes.

Between 1964 and 1969, Alicia emerged as a grassroots activist in Santiago, Chile, where she co-founded a maternal care center in Lo Valledor and took part in collective efforts to formalize Población La Pincoya. Her work highlights the intersection of community care and political struggle, as residents, often led by women, mobilized through land occupations to demand housing rights and challenge state neglect in marginalized urban areas.

Between 1970 and 1984, Alicia and her daughter Iris endured ongoing domestic violence rooted in sexism and transphobia. Iris’s father frequently assaulted her, targeting her gender-nonconformity, while Alicia, who described him as “sexist and unloving,” did what she could to protect Iris, sometimes hiding her in closets or under the bed. Their experience reflects broader systemic failures in protecting trans youth and women from violence within the household. In Chile, legal protections for trans children and adolescents have only recently begun to emerge.

In 1994, Iris decided to leave Santiago, a city where she no longer felt safe or welcome. She called her mother, Alicia, for help. Without hesitation, Alicia bought her a bus ticket to Iquique, allowing Iris to seek refuge with an aunt in the north. This act of care was not only maternal but deeply political; Alicia’s support enabled Iris to leave an urban environment marked by exclusion, and to begin rebuilding her life in a place where she felt more free to express her gender identity and seek employment.

In 2018, Rachel migrated from Venezuela to Chile as an act of economic survival, seeking to support her family by helping her father pay off debts. This decision came at a high personal cost: she had to leave her young daughter behind in Caracas, entrusting her to the care of her parents. Upon arriving in Chile, Rachel began working for her father’s relatives with the initial intention of staying only a few months. However, her trajectory shifted when she met and fell in love with Roberto, a Bolivian migrant. A year later, the couple had a son and relocated to Antofagasta, where they moved in with a brother-in-law, and Roberto took a job in a mining company alongside some of his siblings. Rachel’s story reflects the difficult trade-offs migrant women often face where providing for one’s family means enduring separation and precarity in unfamiliar territories.

In 2005, Alicia and Guillermo were evicted from their home after the bank foreclosed on their mortgage. Guillermo, who had vision problems and limited literacy, intended to take out a loan to expand their home but unknowingly signed a mortgage agreement. After missing a few payments, they lost the house. This incident is not isolated but emblematic of Chile’s post-dictatorship housing model, which shifted risk onto individuals while offering little to no institutional support. Vulnerable families, especially the ones with limited education, health, or financial literacy were left to navigate complex systems alone. Without adequate guidance, many fell victim to predatory lending practices that reinforced cycles of exclusion, effectively punishing the poor for structural failures beyond their control.

Between 2007 and 2008, Iris lost the home she had built in La Negra due to a devastating fire. With everything destroyed, she returned to live with her mother in La Tortuga before later moving in with a friend, a move that reflects both the fragility of self-built housing and the recurring instability faced by those living in precarious urban peripheries.

In 2008, after being evicted, taking with them all the material they had used to expand their previous home. With Alicia, they paid 300.000 pesos for a plot of land in El Boro, where there was no water and no electricity, and with the little money that the bank returned to them, their friends helped build the new home. Despite their persistent individual efforts, precarity resurfaced. Their situation underscores how systemic failures in housing policy are often reframed as personal shortcomings, pushing families back into informality while absolving the state of responsibility.

In 2023, mutual support between Iris and Rachel becomes a foundation for both women’s resilience and growth. Since she struggles to build social ties in the camp and feels isolated from her in-laws, Rachel finds companionship and purpose by helping Iris in her leadership work. In turn, Iris offers Rachel guidance, inclusion, and a sense of belonging. Iris herself has become a powerful voice for her community, advocating for dignified housing and representing her neighbors in the municipality. Their relationship illustrates how solidarity among women, particularly in contexts of informality and marginalization, becomes a vital force for survival and collective empowerment.

Residents’ daily lives unfold within a complex web of relationships, where the boundaries between formal and informal spaces, both in housing and work are blurred. Residents dynamically combine various life strategies.

Nowdays, the informal settlements seem to have made some progress in terms of infrastructure and political power. But despite various reforms, these approaches have never fully addressed the housing crisis in all its complexity, and to this day, thousands of Chileans remain without access to dignified, secure, and well-located homes.

For more details and to get an immersive experience through this story, you can visit the timeline in this link:

https://prezi.com/view/XxeRWQuH7AmgDJBE48L0

Takeaways

The main challenge of this work lied in the filtering of the data we collected to create a coherent and easier to follow narrative. With more time to develop the story, we would further hone the contextualization of structural elements of neoliberal housing policies, perhaps emphasizing in some points the impacts these had and strengthening the connection between these and the experiences of the women. We might also highlight other common threads throughout the stories, emphasizing moments where the women face similar precarities, those based on their identities, their housing status, or the labor they perform (both paid and unpaid).

This crash course in crafting stories highlighted different ways of telling stories, how to think of protagonists and antagonists, various ways of sequencing the narrative (employing flashbacks and jumping to the future), and thinking of the right ways of visual representation (moving from maps to timelines to diagrams).