An intelligent living system as the last decision you will ever make.

Abstract

This project explores Technology and Artificial Intelligence (AI) and their impact on architecture and urban living. Based on complexity theory, ecology, and AI discourse, it frames architecture as an adaptive, self-organizing system rather than a static object. The case study is Barcelona, a dense city constrained by geography and facing housing shortages and gentrification. Focusing on the Gràcia district, the project identifies blind walls from uneven redevelopment as spatial opportunities. The proposal envisions a 2070 optional housing system, Decisionless, where AI forces movement and program through movable pods, prioritizing wellness and social interaction.

Technology and AI

Introduction

We stand in late 2025. Technology and Artificial Intelligence (AI) have already moved beyond theoretical concepts and started affecting our everyday lives. We are witnessing a fundamental shift in basic human activities—altering the way we walk through our cities, the way we approach our work and the way we think and process information.

Over the next four and a half decades, these technologies will evolve from influencing our lives to defining our environment. We anticipate an exponential acceleration in how urban infrastructure, housing, and daily life adapt to autonomous systems and algorithmic living.

Theoretical Analysis

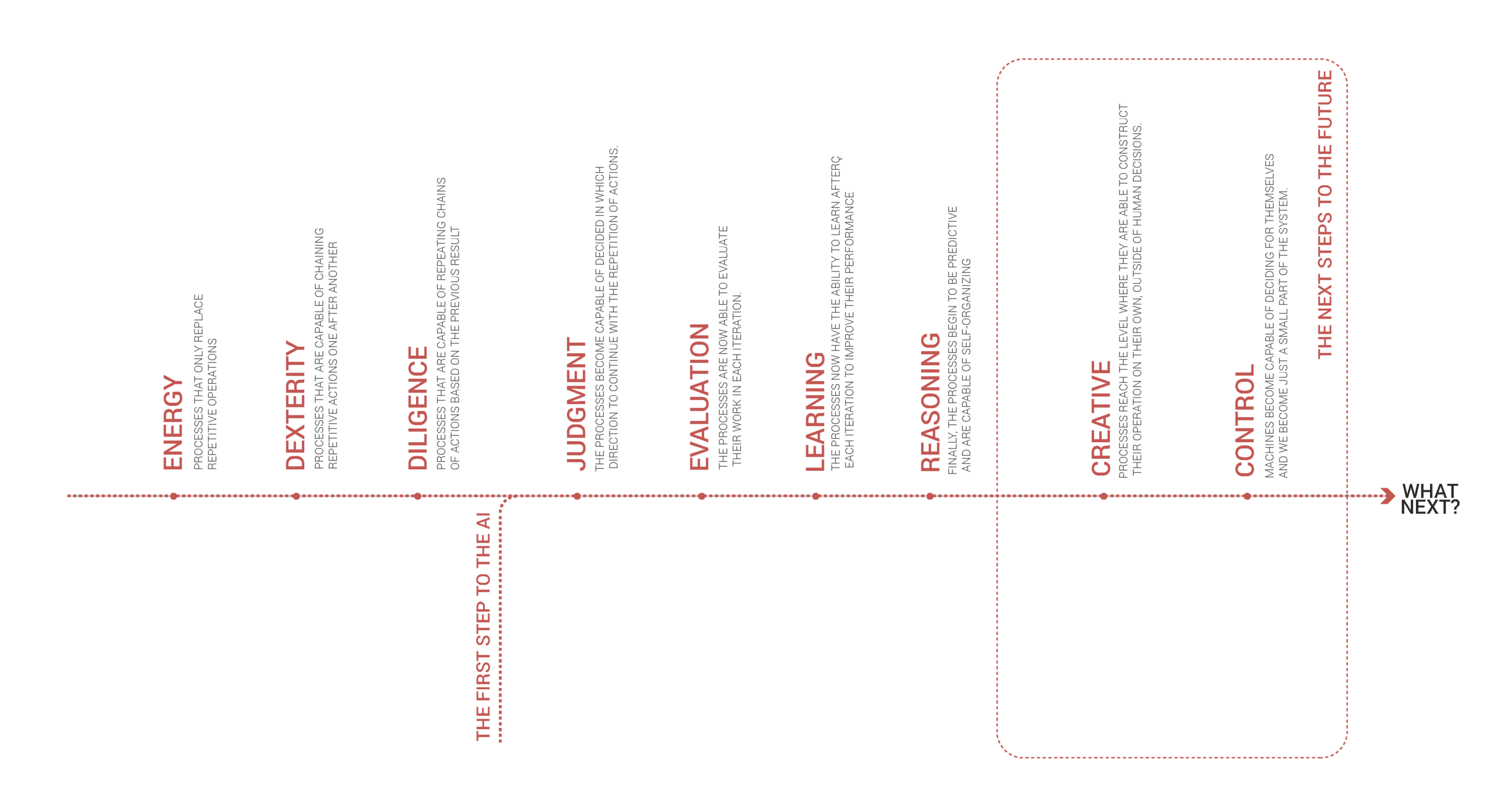

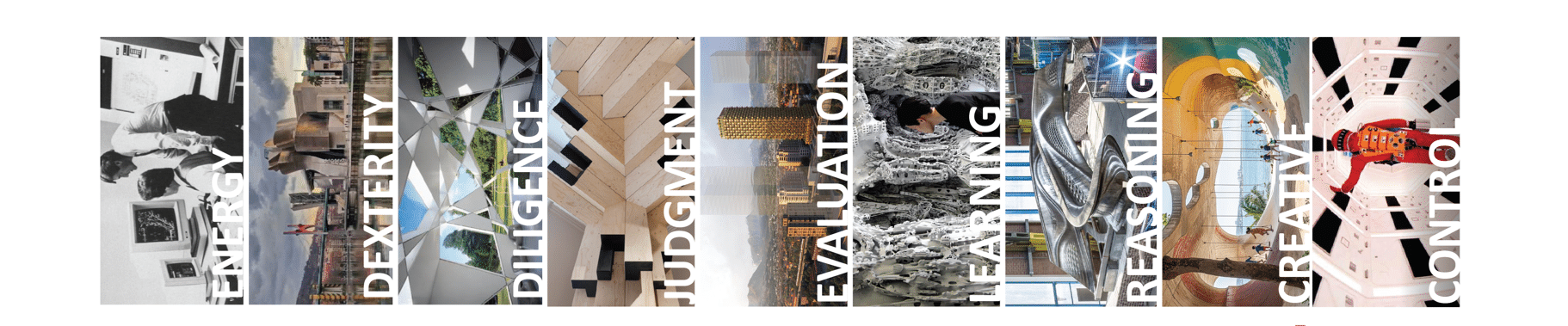

Our research began with a thorough investigation of the scientific literature regarding the emergence of AI throughout time and its effects on the system.

Our research investigates the evolution of AI and its impact on systems, drawing from Fritjof Capra’s “The Web of Life,” which advocates a synthesis of biology, ecology, and systems thinking. Capra introduces the concept of autopoiesis, demonstrating that living systems and human organizations exhibit similar self-organizing patterns, promoting an ecological design paradigm in architecture. Aranda and Lasch’s “Tooling” examines the relationship between natural processes and algorithmic design, highlighting the function of architects as programmers rather than mere creators, thereby promoting a transition towards parametricism and digital fabrication. Barker and Dong’s research on “A Representation Language for a Prototype CAD Tool for Intelligent Rooms” introduces hybrid representation languages and semantic layers, enhancing the dynamism of architectural models and laying groundwork for AI-driven Building Information Behavior (BIB).

“Spiraling produces a shape unlike any other because it is seldom exprerienced as geometry, but rather as energy.”

-Aranda, Benjamin & Lasch, Chris. (2005), Tooling, Pamphlet Architecture No. 27.

Kurzweil’s “The Singularity Is Near” predicts technological advancements leading to a blend of biology and technology, coining the term technological singularity. Terzidis discusses algorithmic versus parametric design, positioning algorithms as new architectural expressions. Žižek critiques green capitalism “In Examined Life,” advocating for an architecture that embraces entropy, while Pauli’s “The Blue Economy” envisions architecture mimicking natural ecosystems. Tegmark in “Life 3.0” calls for ethical governance alongside AI development, and Morton challenges conventional ecological perceptions in “Ecology Without Nature,” promoting a design aesthetic that appreciates ambiguity.

Alkhansari’s journal article suggests a broader conception of architectural flexibility, seeing it as a complex, adaptive characteristic. Wooldridge tracks AI’s development from symbolic to deep learning, urging designers to foster algorithmic literacy. Cañigueral highlights the impact of the digital age on work structures, advocating for flexible architecture that supports diverse employment models.

In computer science, AI is defined as the study and development of intelligent agents (…) In general, the term is applied when a machine mimics the cognitive functions associated with being human.

Matias del Campo & Neil Leach (2022), Machine Hallucinations: Architecture and Artificial Intelligence

Leach’s recent work “Architecture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence” explores the transformative impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on architectural practice, suggesting that while AI will not replace architects, it will significantly alter their roles towards curating generative processes. He differentiates between weak and strong AI, addressing ethical issues such as authorship and algorithmic bias. Leach posits that AI fosters a new design paradigm that shares creative responsibility between humans and machines. He reviews modern tools like GANs and deep neural networks for aesthetic exploration and predicts a future architecture characterized by collaboration, adaptability, and co-intelligence, where designs evolve through experiential learning.

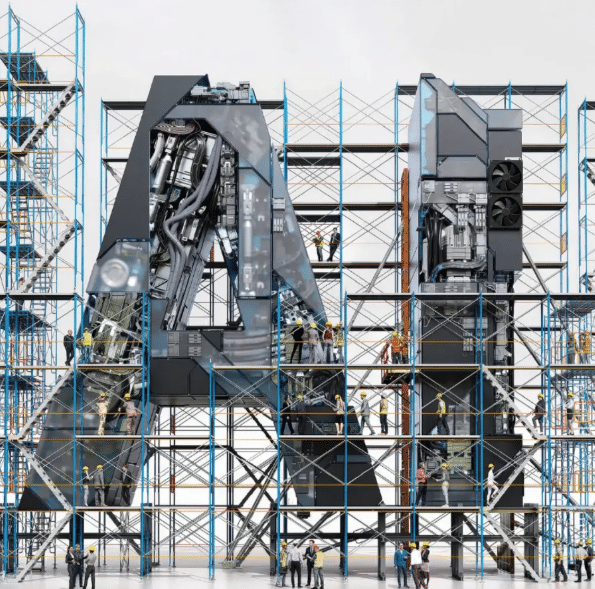

“Each order of automation is tied to the human attribute that is being replaced by either mechanizing or automating it by the machine.”

-Amber and Amber, (1962), Yardstick for automation.

The State of the Art

Digital twins are virtual replicas of physical systems that utilize real-time data for simulation, monitoring, and performance optimization, facilitating predictive analysis and informed decision-making in multiple industries.

Modular robots made of voxels —tiny units that transmit power, data, and force— capable of autonomously connecting to build structures or even replicate themselves. No wires, just structure.

(Figure AI, 2022).

Figure AI is an artificial intelligence robotics company that developed a robot to work essentially in dangerous tasks. The robot is currently able to understand natural language, reason, and move fluidly.

(We Ride & Renault Group, 2024).

Barcelona’s autonomous bus is a self-driving vehicle designed for urban transport wich can navigate, detect obstacles, and interact with traffic systems, offering safe and efficient mobility in real-world conditions.

CREATIVE

The tools are capable of finding new ways to work to our benefit and follow our decisions.

CONTROL

The tools decide how to function, even if it’s not the best for us as humans.

The city of Barcelona

Introduction

Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia and Spain’s second-largest city, is a highly sought-after living destination, noted for its opportunities, creativity, and quality of life. As of 2024, the population reached 1,686,208, reflecting significant demographic growth. The city’s evolution into a dense, attractive urban center is influenced by architectural innovation and urban transformation while facing geographical constraints from the Mediterranean Sea and surrounding mountains and rivers. This limited space underscores the significance of every new resident and development. A key concern is the sustainability of Barcelona’s growth and its ability to maintain its distinct identity amid ongoing change.

Demographics and Growth

“Barcelona’s population has surpassed 1.73 million as of January 1, 2025. The city added nearly 30,000 new residents over the past year, reaching its highest population total since 1985.”

-CatalanNews, (2025),Barcelona reaches 1.73m residents, highest figure in 40 years.

Barcelona’s population dynamics over the past century illustrate significant transformations. In the early 20th century, the population was just over 500,000, peaking at nearly 1.9 million in 1979 before declining. By 2024, the population rebounded to approximately 1.686 million, with early 2025 estimates showing 1.73 million, the highest in four decades. The city, covering only 101 square kilometers, has one of Europe’s densest populations, with high movement and activity within its urban space.

“According to data from the INE Padrón statistics, most of the foreign residents in Barcelona come from the US, Asia, Africa, and Oceania.”

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). (2024).

“The average age stands at 44.4 years old, with more women than men in the city.”

Barcelona.Cat (2025), Barcelona’s population stabilises at 1.7 million people

“If we compare the more than 40,000 new inhabitants who arrived in 2024 with just a few more of 1 thousand new homes that began construction that same year, it’s easy to see that this growth is not enough.”

Historical map during the years

Researching the area of Barcelona and studying it’s map, we separated in historic timelines starting from late 19th century, when the population of began to increase rapidly, due to the implementation of Cerdà Plan, approved in 1859 and the construction of the first houses, single family mansions and continuing up to the 21st century.

Starting from 1890, Barcelona was one of the most important cities in Spain, due to the industrial sector, especially in manufacturing and textiles, which relied heavily on marine trade. The port was synchronized after industrial expansion in the 19th century.

New Cerdà blocks were constructed in 1903 to connect the old city to new areas, and the Eixample district began to grow.

In 1936 the Spanish war begins and the port was a strategic military and supply site. This conflict that ended in 1939 halted economic growth and led to heavy damage to infrastructure, including parts of the harbor, but yet it didn’t affect Eixample, the area we are investigating.

In 1956, the pattern of Cerda blocks reappears in some areas, expanded the area of Eixample in the area that we now called Sagrada Familia and new informal housing techniques started to appear in order to resident people that came to live to Barcelona.

In 1976, the post-franco era the city began to reconnect with its coastline, leading to future urban and post renewal projects.

In 1992, it’s one of the most important years in Barcelona due to the Olympics. The whole city transformed rapidly in order to host millions of people coming all over the world. The old industrial port area was redeveloped into Port Olímpic, beaches were restored, and the Port Vell (Old Port) became a leisure and tourism hub.

In 2004, the port of Barcelona became one of the Mediterranean’s busiest container ports. Surge in cruise tourism; new logistics zones developed in Zona Franca.

In 2010, due to the global crisis, it remained a global city, but also one of Europe’s busiest cruise ports.

In 2025, the port of Barcelona is among the top 10 European ports by volume and a leading cruise destination. It’s now central to the city’s “Blue Economy” strategy. The city emphasizes sustainability, digitalization, and tourism management. Barcelona is the second-largest city in Spain, but ranks fifth in Europe for its urban area population, which is around 5.7 million people. Globally, the city’s urban area is ranked around 70th in the world by population.

Problematic Analysis

Barcelona’s success as a vibrant international city has led to severe urban tensions, most notably around housing affordability and gentrification. Housing is now the top concern for residents—surpassing safety and tourism in municipal surveys—as the gap between supply and demand continues to widen (Catalan News). Despite periodic increases in construction, the city has consistently failed to deliver enough new homes. Catalonia faces an estimated annual shortfall of around 10,000 housing units, with Barcelona particularly constrained by restrictive planning frameworks, limited land availability, and high land costs (El País).

Gentrification has significantly reshaped many central neighborhoods. Long-term residents—often lower-income households—have been displaced as investment, tourism, and speculative development drive up rents and property values. Areas such as Sant Pere, Santa Caterina, La Ribera, El Raval, and Barceloneta have become spots where redevelopment has altered the social and economic fabric of daily life (Barcelona.cat). The problem is intensified by large-scale speculative luxury projects—more than 600 reported in 2024—and by the city’s limited supply of social housing, which represents less than 2% of total housing stock, far below European averages (ARA.cat).

“Barcelona’s global success has produced a deep housing crisis, as constrained supply, speculative development, and tourism-driven demand displace long-term residents, deepen inequality, and threaten the city’s social diversity unless planning and housing policy are fundamentally rethought”

-Catalan News; El País; Barcelona.cat; ARA.cat.

These housing pressures intersect with broader urban and social challenges. Rising rents, near-zero vacancy rates, and a shrinking supply of affordable homes have pushed many residents to relocate to surrounding metropolitan municipalities in search of more attainable housing. At the same time, inner-city neighborhoods increasingly cater to wealthier newcomers or short-term tourist accommodation, further eroding residential stability.

Barcelona now stands at a critical crossroads. Its density, economic vitality, and global appeal offer significant opportunities, but they also intensify structural inequalities. Housing costs continue to outpace incomes, while climate stress, rising energy prices, and energy poverty deepen social vulnerability. Without faster planning approvals, stronger regulation of speculative activity, expanded public and social housing, and more innovative approaches to density and land use, the city risks a long-term loss of affordability and social diversity. Leveraging data-driven planning tools and redefining how density is delivered will be essential to ensuring resilient, inclusive urban living for Barcelona’s future.

The area of Gracia

The historical maps of Barcelona reveal that Gràcia existed before the Cerdà blocks—a small village (Vila) beyond the city’s boundaries, whose traces remain visible today.

Unlike the Eixample, Gràcia kept its irregular street network, creating a unique urban fabric where village structures coexist within a large city. This made it a desirable area for new residents, while locals have preserved the neighborhood’s identity, often making it difficult for newcomers to fully integrate.

Today, Gràcia has about 50,670 residents and covers 0.512 square miles. Its high density reflects sustained urban vitality, while surrounding sectors like el Farró show how peripheral areas gradually integrated into the city grid while keeping local character. Gràcia remains a key case study in urban planning, showing how historic settlements can adapt within expanding cities while balancing heritage and modern needs.

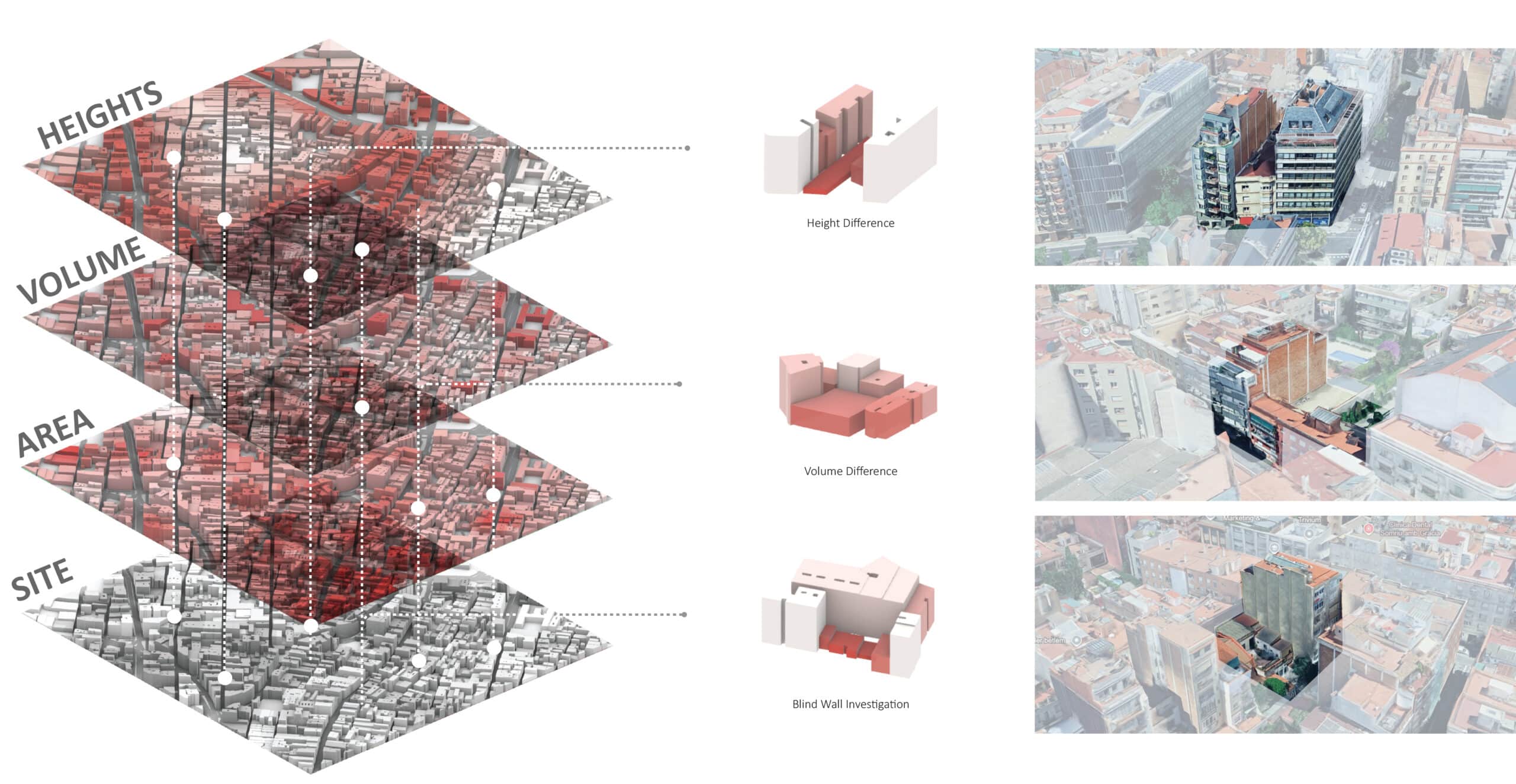

The Blind Walls of Gracia

Our interest in investigating the Gràcia neighborhood began with our existing data, as it is one of the oldest areas near the city of Barcelona. In contrast to the structured Eixample district, separated by the major Diagonal road, Gràcia offers a more irregular and organic urban fabric. Exploring the area firsthand, we became aware of a strikingly unpleasant element: the blind walls.

Due to the high demand for housing in Gràcia, some older buildings have been demolished to make way for new residential developments. This has created abrupt height differences between structures, resulting in blank walls that cannot be addressed without demolishing neighboring buildings as well.

We saw this as an opportunity to develop our project. Instead of following the traditional vertical approach, our proposal seeks to expand along the axis of these blind walls.

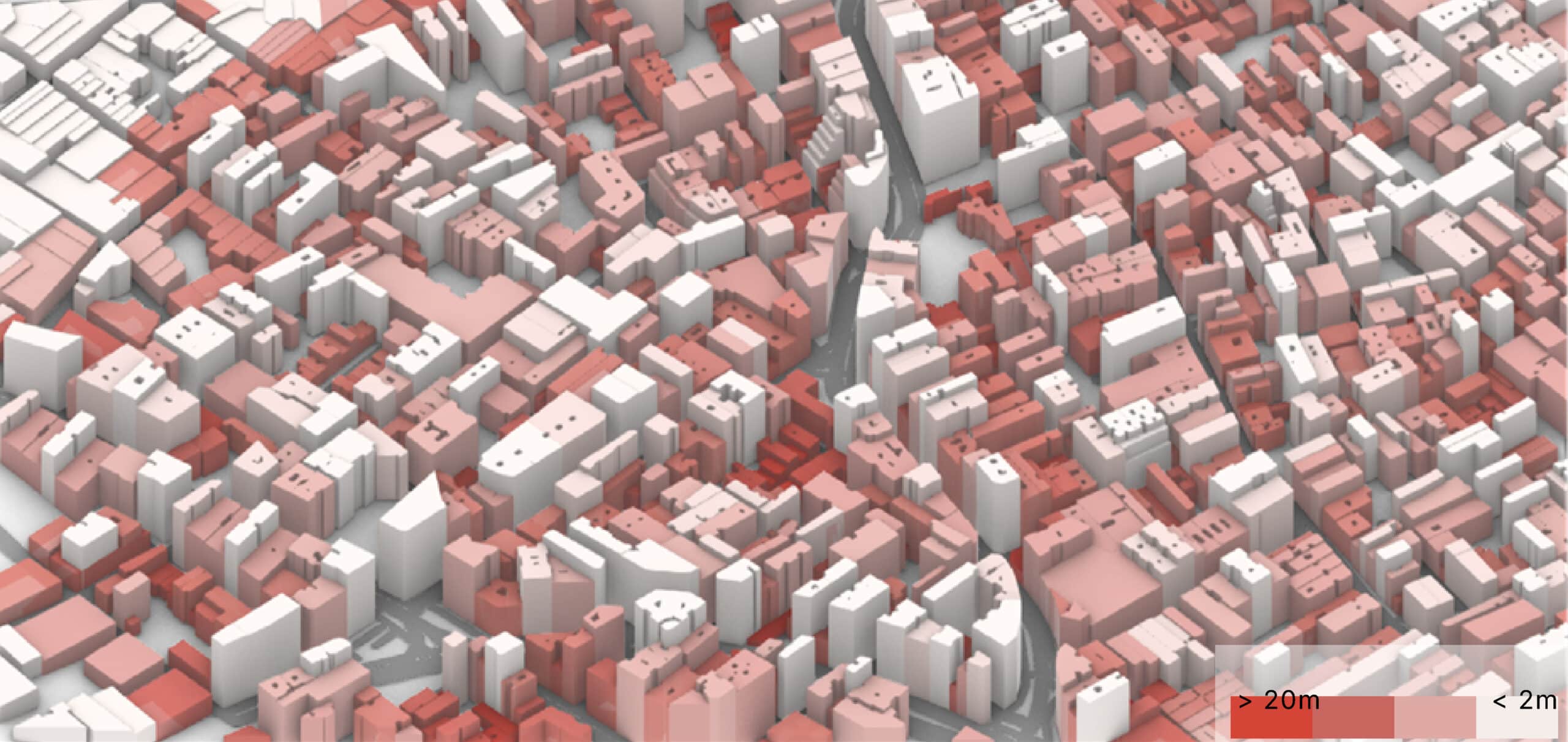

Site Morphological Study

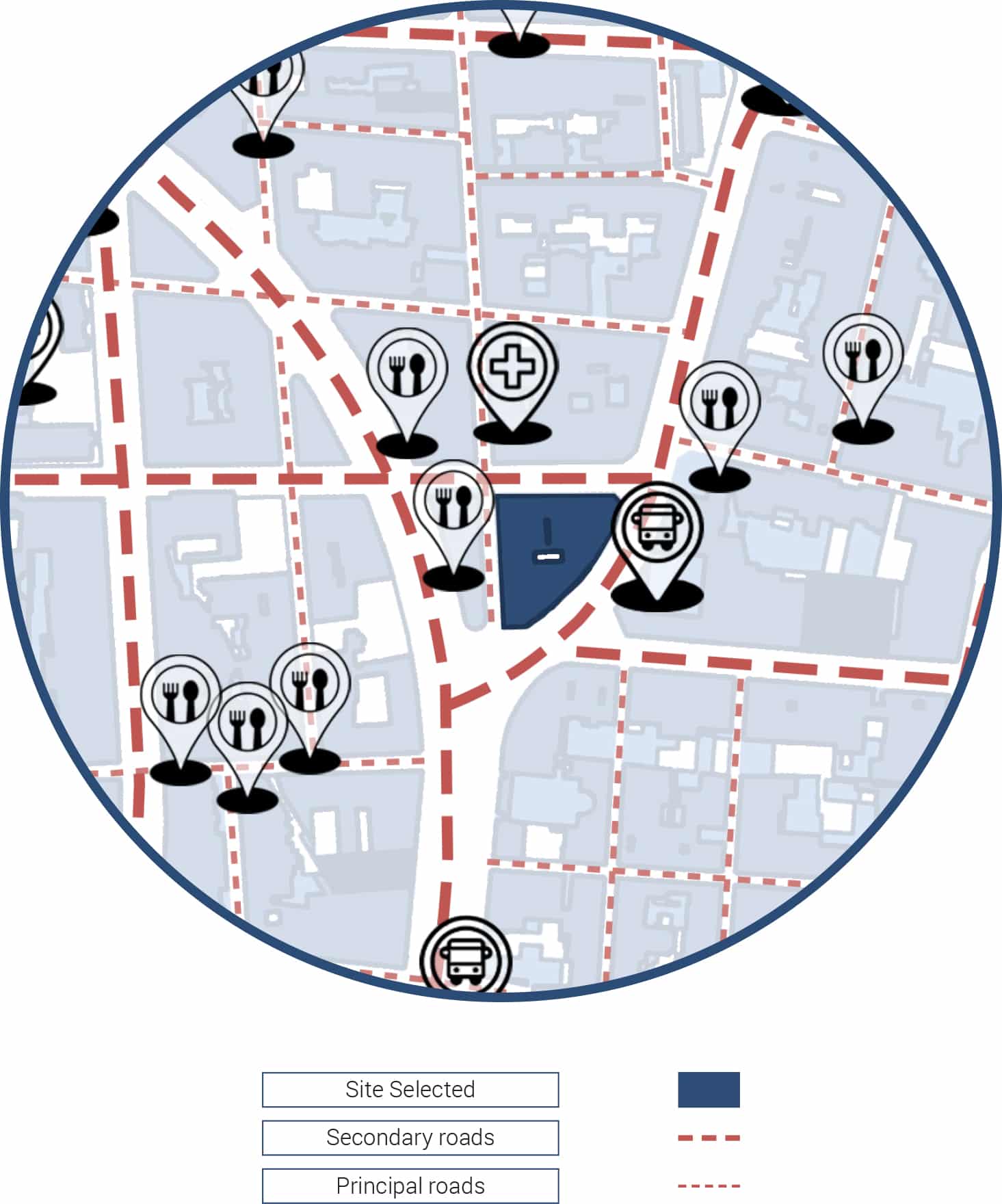

Our investigation of the selected site began with an analysis of the Gracia district. The selected area was analyzed through the examination of variations in building heights within the preferred site blocks, the dimensions of the blocks themselves, and the surrounding services and amenities present in the immediate context.

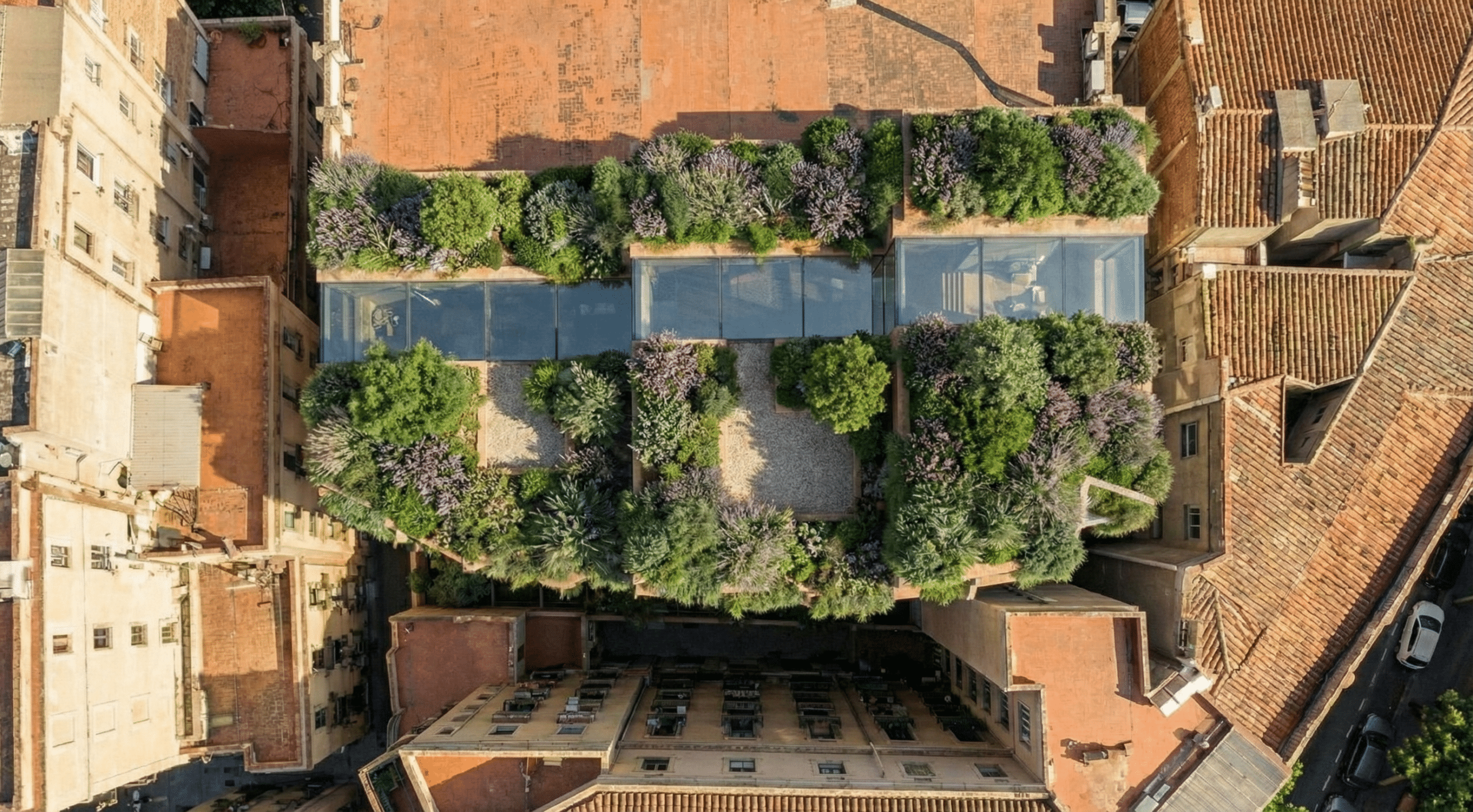

The site that we took as an opportunity to start our project is located in the L’Avinguda de la Riera de Cassoles area, a sub-neighbourhood of the Gràcia district, are located in a dense, low-rise, and culturally active area. The area features compact streets, plazas, and mixed uses, making it ideal for analyzing density and liveability in Barcelona. It is quieter than tourist-heavy Gràcia cores, making it suitable for new housing typologies that cater to everyday residents, migrants, and changing household forms.

System Design

Our interest in investigating the Gràcia neighborhood began with our existing data, as it is one of the oldest areas near the city of Barcelona. In contrast to the structured Eixample district, separated by the major Diagonal road, Gràcia offers a more irregular and organic urban fabric. Exploring the area firsthand, we became aware of a strikingly unpleasant element: the blind walls.

Due to the high demand for housing in Gràcia, some older buildings have been demolished to make way for new residential developments. This has created abrupt height differences between structures, resulting in blank walls that cannot be addressed without demolishing neighboring buildings as well.

We saw this as an opportunity to develop our project. Instead of following the traditional vertical approach, our proposal seeks to expand along the axis of these blind walls, transforming them from obstacles into design opportunities.

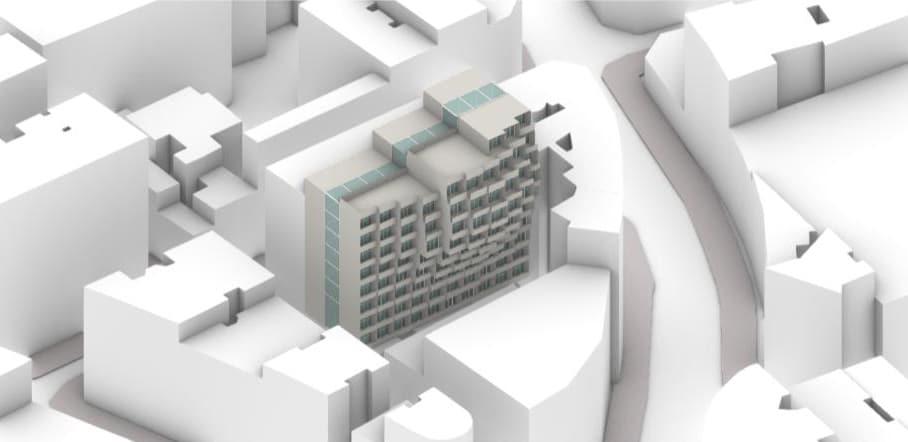

The proposal envisions solutions for Barcelona in 2070, addressing future technological and urban realities while reimagining Ildefons Cerdà’s Eixample blocks. Originally designed in 1860 to improve the industrial city’s physical conditions through geometric layout promoting hygiene and light, the contemporary challenge has shifted from physical ailments to mental health issues stemming from a hyper-accelerated society dominated by Artificial Intelligence (AI).

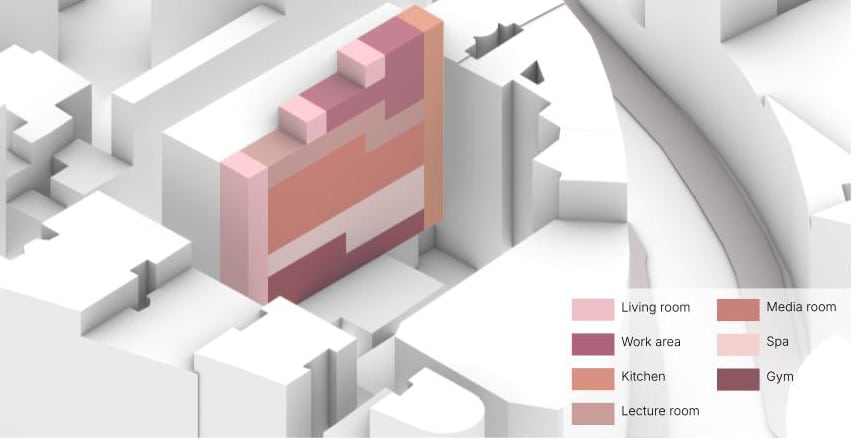

This Movable Pod is the way of transition. It is a minimalist void designed to reset the resident’s mind between activities. Inside, there are no controls and no choices. The resident enters, and the AI navigates the deliver them, or even forces them seamlessly to their next required destination—whether it be the gym, the kitchen, the library etc.

This is Decisionless, an optional housing system that emphasizes wellness and personal development. Residents move in the space using kinetic pods, reinforcing the idea that true wellbeing may be achieved through thoughtful infrastructure rather than ownership. This approach aims not just to create a more functional city but to foster an improved human experience.

(diagram by Author, 2025).

The proposed system targets the “blind walls” of the Gracia district, introducing a metabolic infrastructure aimed at healing urban scars. It highlights the control exerted over residents who own nothing, as their lives are dictated by AI. The innovative core of this concept is AI governance, which prioritizes enforced actions over personal choice. This system effectively reduces decision-making burdens by ensuring that individuals are guided toward their aspirations. For instance, those wishing to enhance their painting skills are physically moved to the creative space, while others that want to work out are forced to go to the gym.

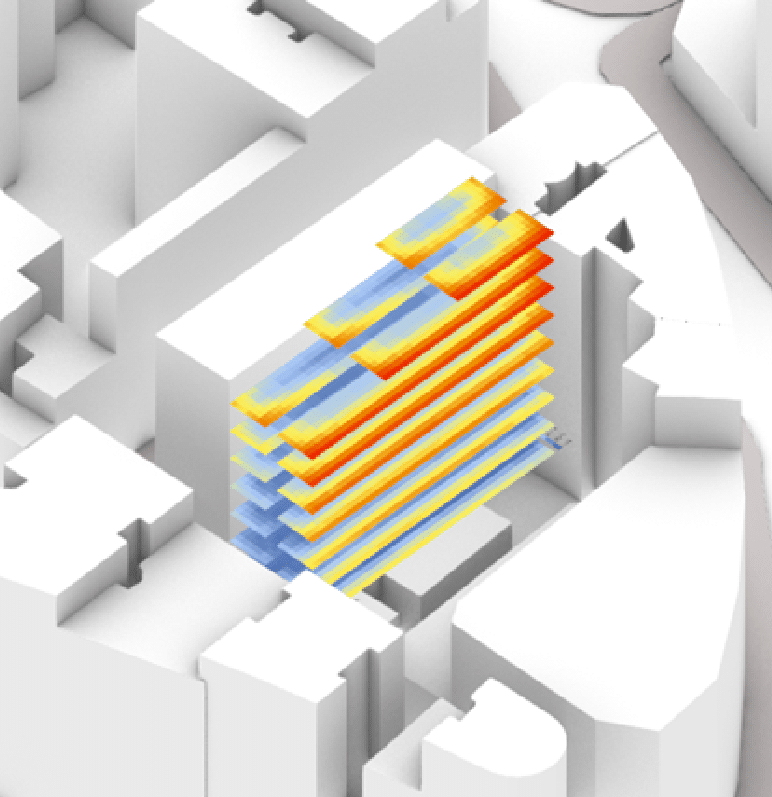

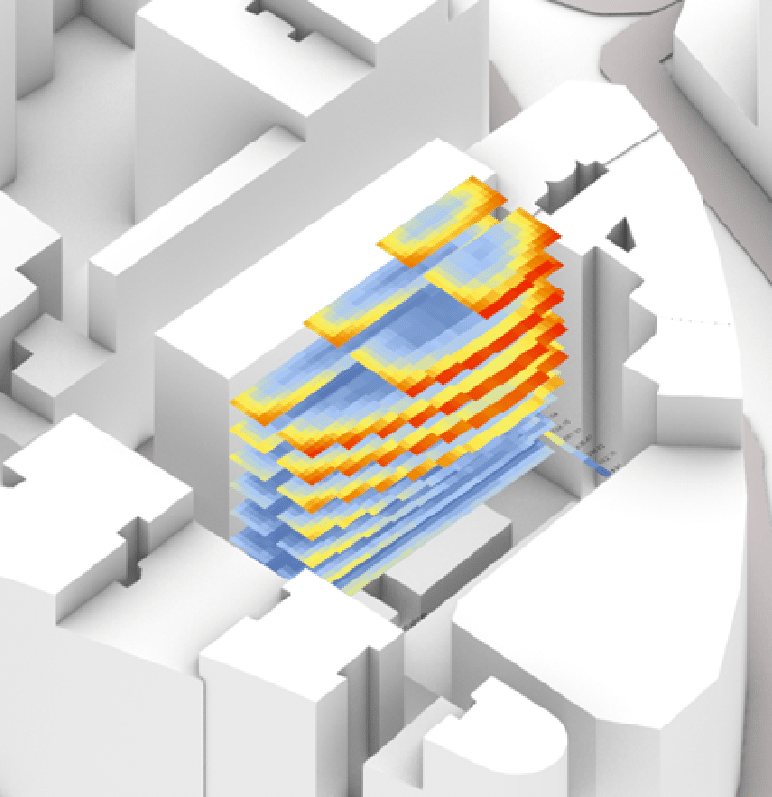

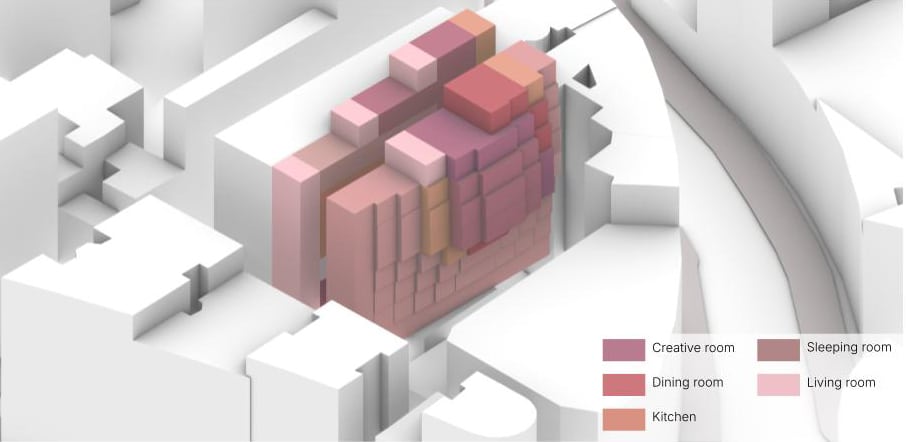

Design Process

The design process emerged from a zoning approach, with the intention of creating a repeatable system. This was seen as an opportunity to rethink conventional vertical organization. The proposal expands along the axis of the blind walls, transforming what are typically considered limitations into generators of architectural form.

The activities were arranged according to the perceived requirements of the system. The system consists of a service zone integrated along the blind walls, a gap that accommodates the movement of the movable pod, and additional services located in the exterior core, which are essential to the overall building system.

The Decisionless Project