Emergy/?n??d?i/[Noun]

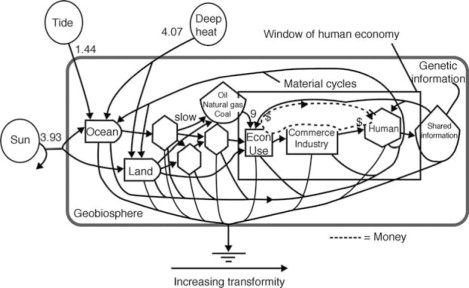

Emergy is the amount of energy consumed in direct and indirect transformations to make a product or service.

Emergy is a measure of quality differences between different forms of energy. Emergy is an expression of all the energy used in the work processes that generate a product or service in units of one type of energy. Emergy is measured in units of emjoules, a unit referring to the available energy consumed in transformations. Emergy accounts for different forms of energy and resources (e.g. sunlight, water, fossil fuels, minerals, etc.) Each form is generated by transformation processes in nature and each has a different ability to support work in natural and in human systems. The recognition of these quality differences is a key concept.

Howard T. Odum who coined the term describes “real wealth” as central to construction ecology. “Whereas money measures what people are willing to pay for products and services,” Odum and Elizabeth Odum note, “emery measures real wealth, including both work contributed by environmental systems and that contributed by humans. Money and markets function well enough on the scale and time of human lives, but are inappropriate on the smaller scales of environment and the larper scales of geology and global formation.”

Only the ecosystem science-based emergy method developed by Howard T. Odum adequately integrates key thermodynamic concepts such energy, material, system boundary, and transformation broadly enough to adequately describe building as a terrestrial process. Though construction ecology & grounded in ecosystem science, it is not reducible to natural science.

Unequal Economic Exchange[Noun]

When there is an unequal trade and exchange in world-systems which often leads to economic imbalances,with real wealth concentrated in the core and extracted from the periphery.

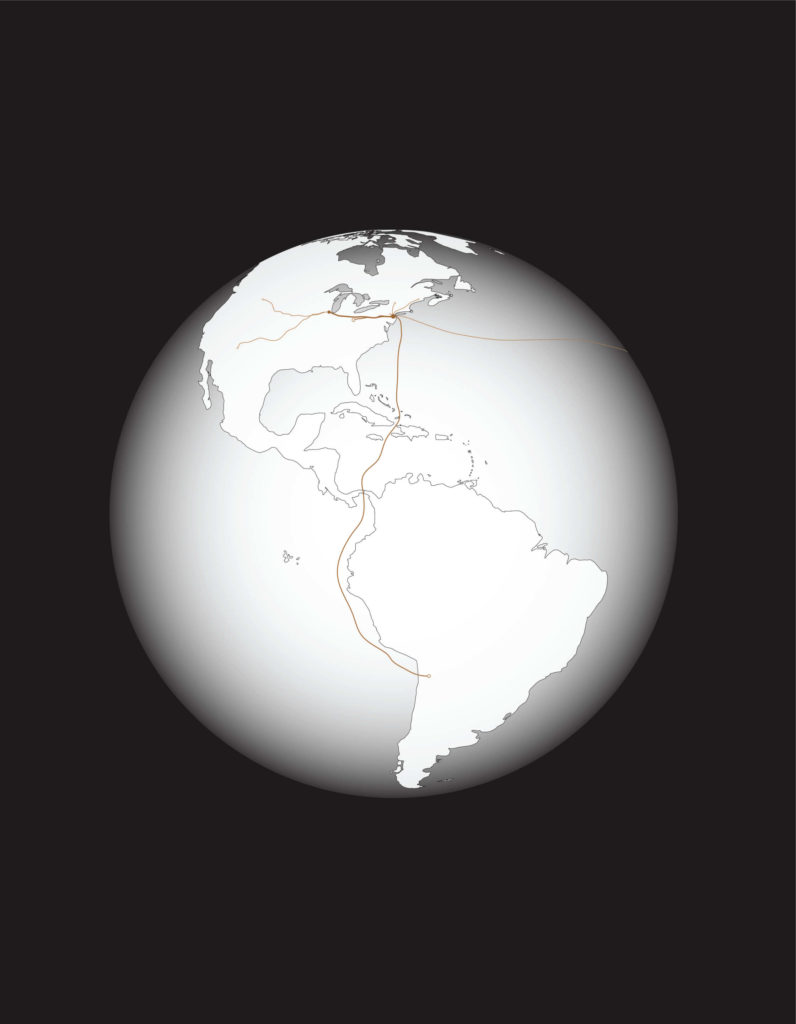

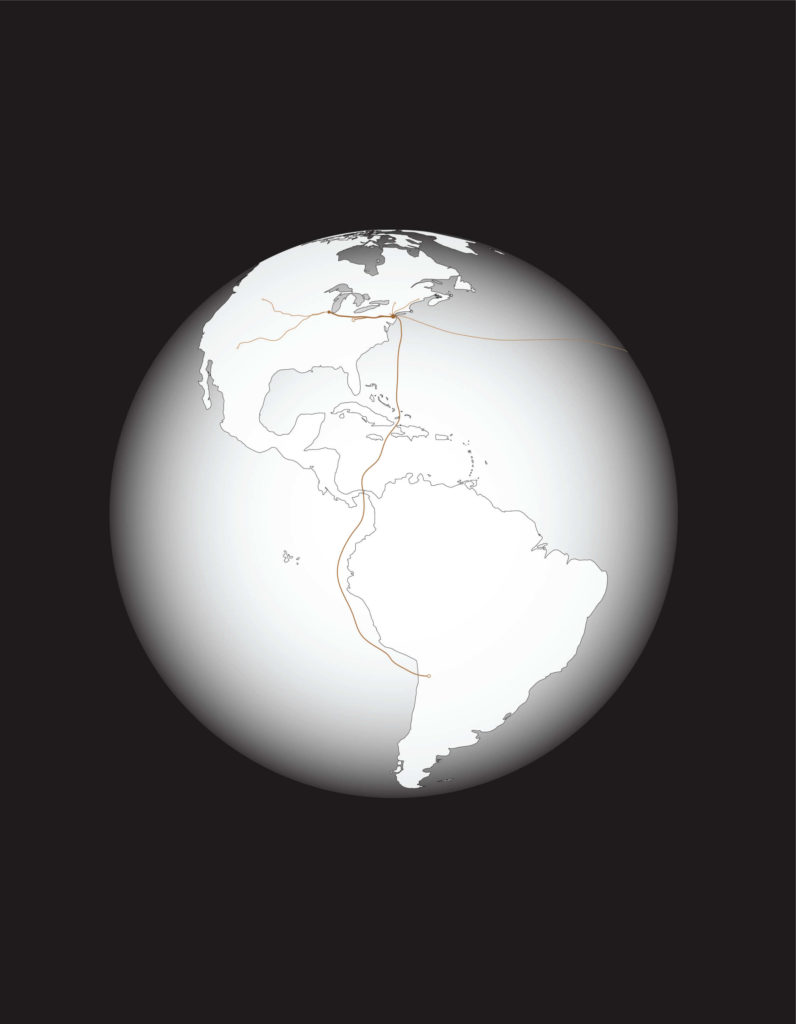

The unequal economic exchanges that tend to accumulate resources in global capitals through architecture, always at the cost of extractive hinterlands and peoples. We can describe how building in one part of the world literally displaces environmental loads to other parts. In that way, we can be newly mindful of how people and places around the world become structurally underdeveloped as global capitals become arguably overdeveloped. These unequal systems and exchanges need to be not only described but also designed before architects, engineers, ecologists, or clients hazard any claim about sustainability, resilience, or environmental justice, or contemplate any Green New Deals. Otherwise, today’s vertiginous physical and political disparities will only be perpetuated and exacerbated through our tradition of abstraction in architectural design. If we blindly follow that tradition, we will continue to make the future a colony of the present. The theory of unequal ecological exchange is pertinent to contemporary architecture because it provides specific and robust insights into the material -energy basis of buildings social and political dynamics. It offers a cogent way to foreground key dynamics of architecture that otherwise remain abstract and external to the discipline.

Moreover, it helps provide a framework for further insight into spirited debates about the separation of the social and natural sciences . As already noted, it is not sufficient to simply acknowledge that society and nature mix. How they mix—that is, specifically how human systems exchange the material and energy of ecological systems in specific ways—Is essential.

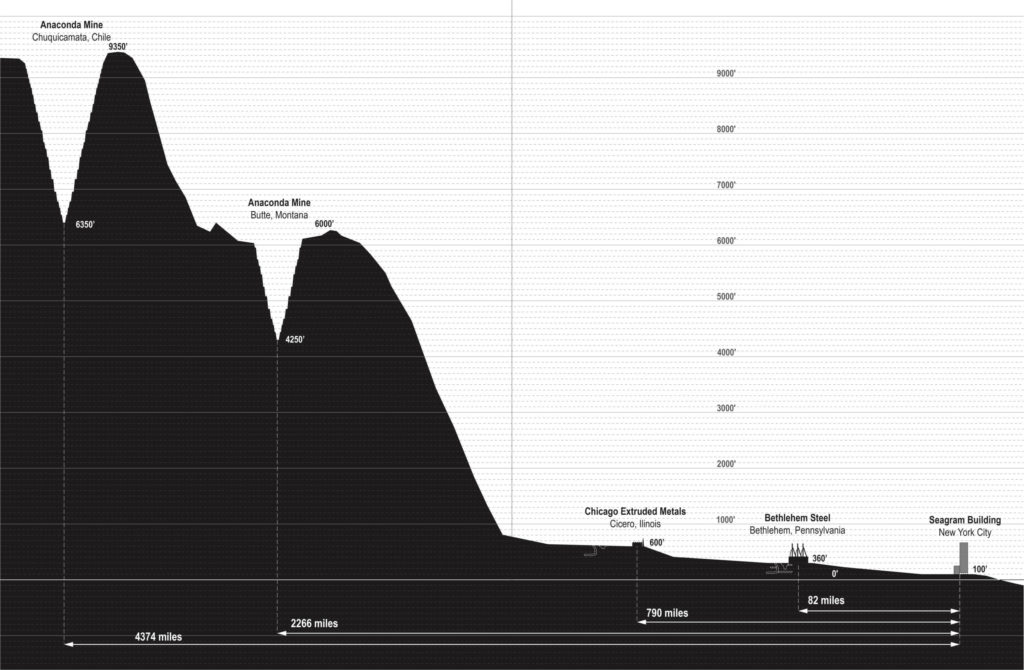

In the case of the Seagram Building, copper minerals deep in the ground below Butte, Montana and Calama, Chile, for instance, would not otherwise appear in Manhattan as a brass alloy in a corporate office building without a specific set of terrestrial exchanges. Activities that are unique to the human species organize and distribute nature in specific ways. Thus a contemporary account of architecture as a terrestrial activity would be incomplete without an account of human-generated unequal ecological exchanges.

In the book’s most effective diagram, the Seagram Building appears puny next to the mountains of resources required for its realization. (Kiel Moe/Courtesy ACTAR)

Material Geography(Noun)

Material geographies considers the geographical journeys materials have undertaken through sourcing and production. This covers aspects of local sourcing and production, but also how a globalized production system gives easy access to geographically distant resources.

‘’Each material has its specific characteristics in which we must understand it if we want to use it.In other words, no design is possible until the material with which you designare completely understand’’

Mies Van der Rohe

Material geography is essential, which involves tracing the material and energetic flows from the geological engenderment, their transformation through myriad terrestrial process, to the their extraction and harvesting, their transportation and processing, and onwards to their formatting into building materials, products, and fuels. All that is required to trace the terrestrial inputs to building. Next, questions about construction, maintenance, replacement, demolition, and disposal extend the spatial -temporal dynamics of building and un-building, Adding to the complexity of building, emergy analysis ako tracks the outputs of the system, and most importantly the feedback of the system. It asks: To what end, to what effect, do these vast terrestrial processes cohere through architectures

Material Geography[Noun]

Material geographies considers the geographical journeys materials have undertaken through sourcing and production. This covers aspects of local sourcing and production, but also how a globalized production system gives easy access to geographically distant resources.

‘’Each material has its specific characteristics in which we must understand it if we want to use it.In other words, no design is possible until the material with which you designare completely understand’’

Mies Van der Rohe

Material geography is essential, which involves tracing the material and energetic flows from the geological engenderment, their transformation through myriad terrestrial process, to the their extraction and harvesting, their transportation and processing, and onwards to their formatting into building materials, products, and fuels. All that is required to trace the terrestrial inputs to building. Next, questions about construction, maintenance, replacement, demolition, and disposal extend the spatial -temporal dynamics of building and un-building, Adding to the complexity of building, emergy analysis ako tracks the outputs of the system, and most importantly the feedback of the system. It asks: To what end, to what effect, do these vast terrestrial processes cohere through architectures.

- Unless illustrates how the Seagram Building was in actuality a hemispherical project, comprising human and material resources drawn from Chicago, Chile, and all over. (Kiel Moe/Courtesy ACTAR)