Accidental Sustainability [Noun]

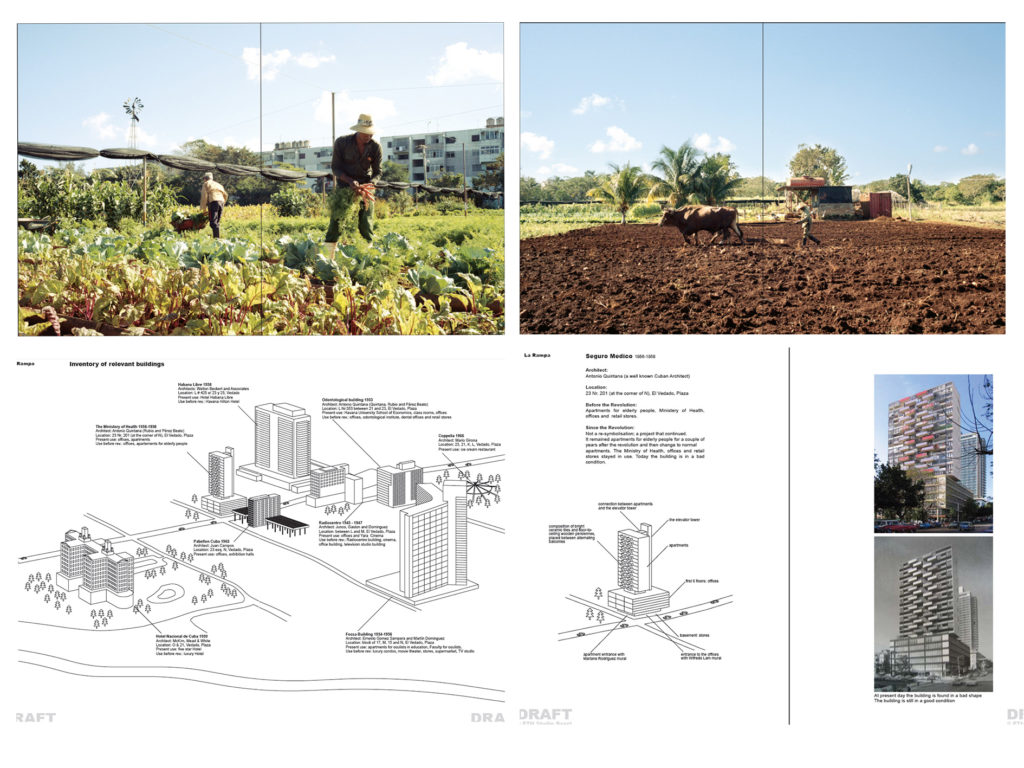

In the mid-1990s, Cuba experienced economic depression and a collective food crisis after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In this ‘Special Period’ , the lack of capital and resources necessitated preserving and maximizing the island’s natural resources. It led to the introduction of organic agriculture. The citizens also started sharing and reusing materials, such as automobiles and apartment buildings. What started as a necessary survival strategy for the Cubans has now evolved into a rich culture of repair and reuse.

Orlando Inclán, an architect and planner with the Office of the City Historian in Havana, calls this an ‘accidental sustainability’, “borne of necessity”.

Since 2000, urban agriculture has become a permanent type of land use in Havana’s master plan. This recognition has paved the way for a more critical, integrated, and perhaps effective future role for agriculture in the city.

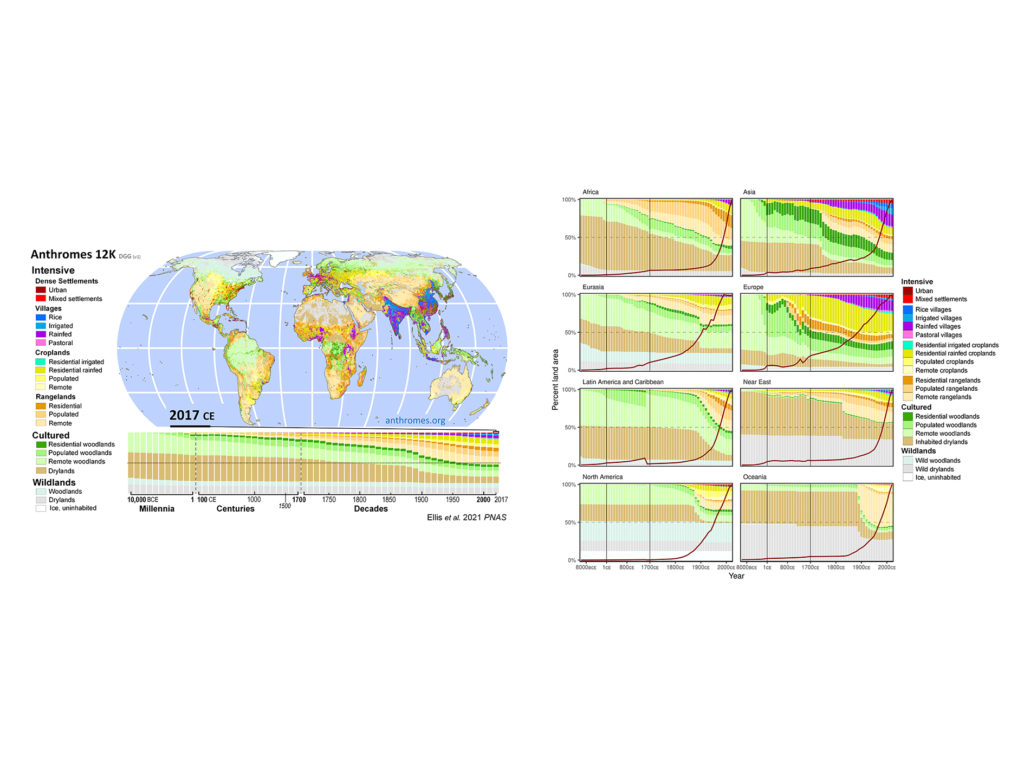

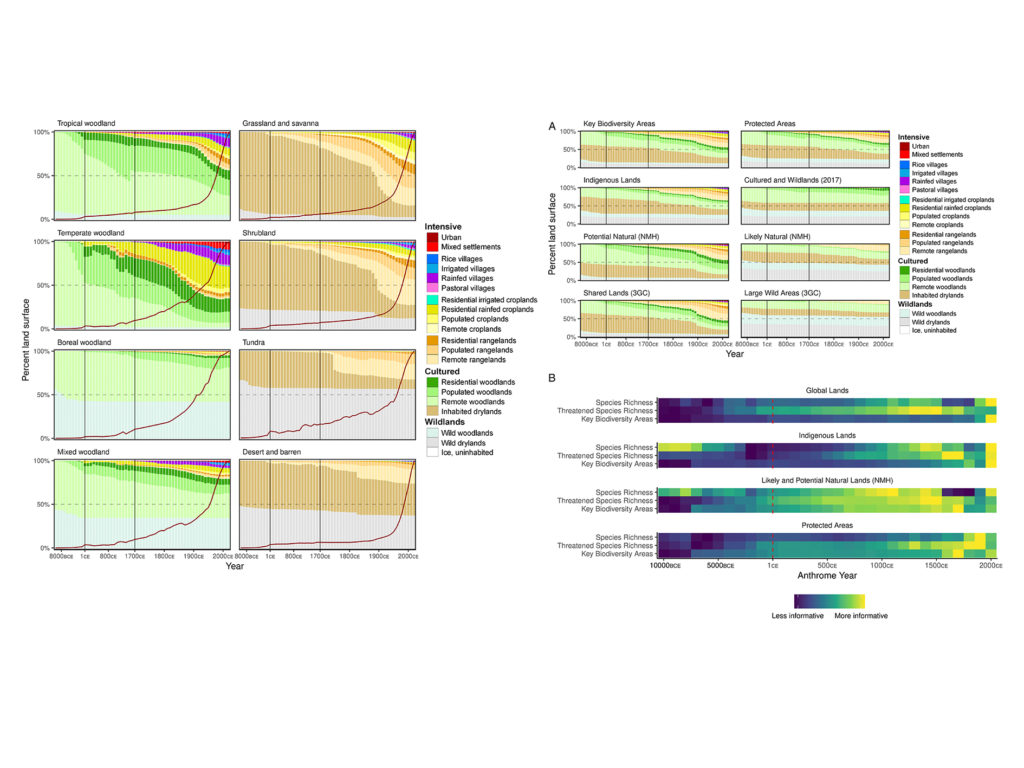

Anthromes, Anthropogenic biomes [Noun]

Anthromes are the global ecological patterns shaped by direct human interactions with ecosystems. Also known as “human biomes”, anthromes are “anthropogenic biomes”, a term coined in a 2008 publication (Putting People in the Map: Anthropogenic Biomes of the World) by Erle Ellis and Navin Ramankutty. Anthropogenic biomes describe the terrestrial biosphere in its contemporary, human-altered form, offering a new way forward for ecological research and education.

Deep Ecology [Noun]

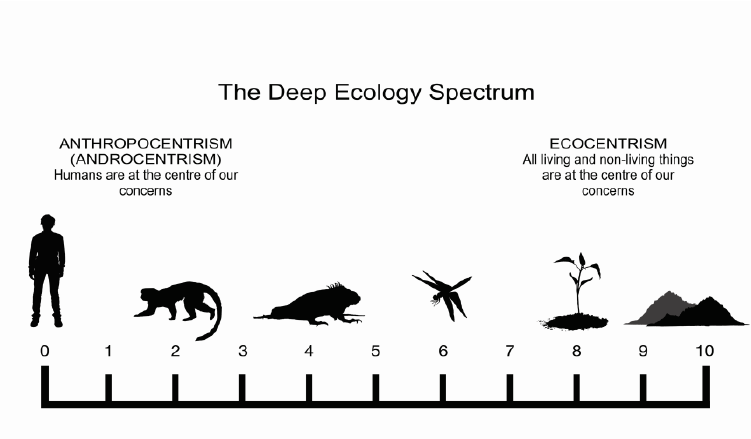

Norwegian philosopher, Arne Næss started the deep ecology movement in 1972. Deep ecology is an environmental philosophy that promotes the inherent worth of all living beings regardless of their instrumental utility to human needs. Deep ecology’s core principle is the belief that the living environment as a whole should be respected and regarded as having certain basic moral and legal rights to live and flourish, independent of its instrumental benefits for human use.

In 1985, Bill Devall and George Sessions summed up their understanding of the concept of deep ecology with eight tenets of deep ecology. They are intrinsic value, diversity, vital needs, population, human interference, policy changes, quality of life, and obligation of action.

Extractivism [Noun]

Extractivism is the removal of large quantities of raw or natural materials, particularly for export with minimal processing. The concept emerged in the late 1900s (as extractivismo) to describe resource appropriation for export in Latin America.

In Extraction and Extractivism, the authors (Durante et al, 2021) describe extractivism as “a particular way of thinking and the properties and practices organized towards the goal of maximizing benefit through extraction, which brings in its wake violence and destruction.”

Frugality [Noun]

The concept of Frugality is defined as “a central and distinctive feature of a sustainable lifestyle warranting reduced consumption and thereby reduced impact of behavioral practices on the ‘availability and renewability of natural resources’.”

Lastovicka et al. (1999) defined frugality early on as a “lifestyle trait reflecting disciplined acquisition and resourcefulness in product and service use.

Common techniques of frugality include reduction of waste, seeking efficiency, defying expensive social norms, embracing cost-free options and staying well-informed about local circumstances and market and product/service realities.

Landscape Ecosophy [Noun]

The term ecosophy was coined in 1973 by Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss, founder of the deep ecology movement. He connotes ecosophy as “a philosophy of harmony with nature or ecological balance.”

Felix Guattari describes ecosophy as “the combination of the three ecologies (the environment, social relations, and human subjectivity) that the individual role – and especially the perception of subjective dynamics that command actions–becomes vital for ecological urbanism.”

In the article Towards a landscape ecosophy, the authors Gonzalo Salazar and Daniela Jalabert have mentioned: “A landscape ecosophy also demands “placing” or “localizing” ecological urbanism. This is to say, to plan and design the city and its relationship with a major landscape based on socio-cultural capacities, ecological limits and personal subjectivities of the various actors within the system.”

Lo-TEK [Noun]

Lo—TEK, an acronym for (Lo-)tech + (T)raditional (E)cological (K)nowledge

Julia Watson defines Lo-TEK as “a design movement to rebuild an understanding of indigenous philosophy and vernacular architecture that generates sustainable, climate-resilient infrastructures.”

TEK is “a field of study in anthropology defined as a cumulative body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs, handed down through generations by traditional songs, origin stories, and everyday life.”

While indigenous technologies have been considered primitive, they are based on complex ecological relationships. These technologies are born of symbiotic relationships with our environment that are powered by nature. They provide multiple ecosystem services such as increasing biodiversity, food production, flood mitigation, bioremediation and carbon sequestration.

Urban Political Ecology [Noun]

The origins of the term ‘urban political ecology’ can be traced to an essay by Erik Swyngedouw, published in 1996.

Urban political ecology (UPE) is “a geographic approach geared toward understanding the ways in which political, economic, and ecological processes work together to transform cities and the lives of the people who live in them.” It seeks to understand how urban environments are created, who takes decisions regarding the urban environment, how are decisions made and who benefits from these decisions. UPE “also seeks to imagine more just and sustainable political-economic systems, as well as democratic systems that ensure a more equal distribution of power in society.”

Roger Kiel, in his paper Urban Political Ecology, elaborates on the origins and the components of urban political ecology as follows:

“The urban is a complex, multiscale and multidimensional process where the general and specific aspects of the human condition meet. (Lefebvre, H., late 1960s)”

“The political is constituted by distributional and systemic inequities in the socioeconomic order that underlies the societal relationships with nature both worldwide (North/South) and locally (environmental justice). The much discussed shift from government to governance has brought into sharper relief nonstate actors in urban and environmental governance (Gibbs and Jonas, (2000).”

The ecology comes from Marxist with “the notion of “metabolism” and concerns itself with the “interwoven knots of social process, material metabolism and spatial form that go into the formation of contemporary urban socio natural landscapes” (Swyngedouw and Heynen, 2003, p. 906).”