Cairo, Egypt’s vibrant capital, exemplifies rapid urbanization in the Arab world. The city’s growth presents multifaceted challenges, from housing to transportation, reflecting modern urban planning complexities. This project explores Cairo’s development strategies, linking them to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 11: “Sustainable Cities and Communities.” By examining Cairo’s case, we gain insights into how global goals translate into local realities, balancing growth, sustainability, and inclusivity.

Cairo is the largest city in the Arab world and the capital of Egypt. It is located in the northeastern part of the country, positioned strategically along the northern section of the Nile River. This position has historically provided fertile land to the city, yet rapid urbanization has led to environmental degradation and loss of green spaces.

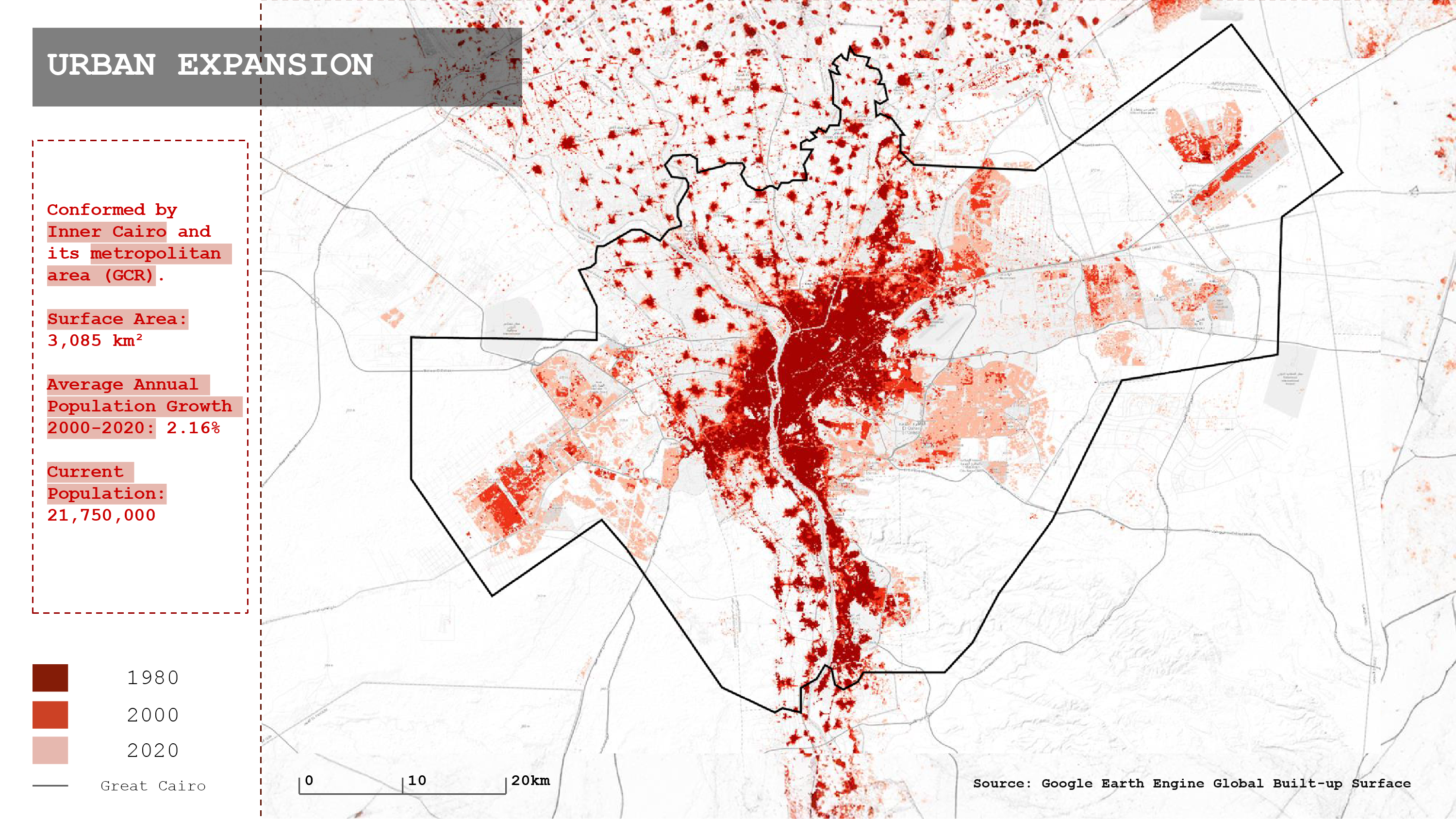

The metropolitan area of Cairo (referred as Greater Cairo Region – GCR) encompasses multiple governorates (Cairo, Giza, Qalioubiya), with governance primarily coordinated at the national level. It covers an area of 3.085 km² and has evidenced an average annual growth rate of 2.16% between 2000 and 2020, reaching a current population of 21.75 million.

Its population has been expanding with a differential spread showing a highest concentration in the center of the city, and new less dense agglomerations in the periphery.

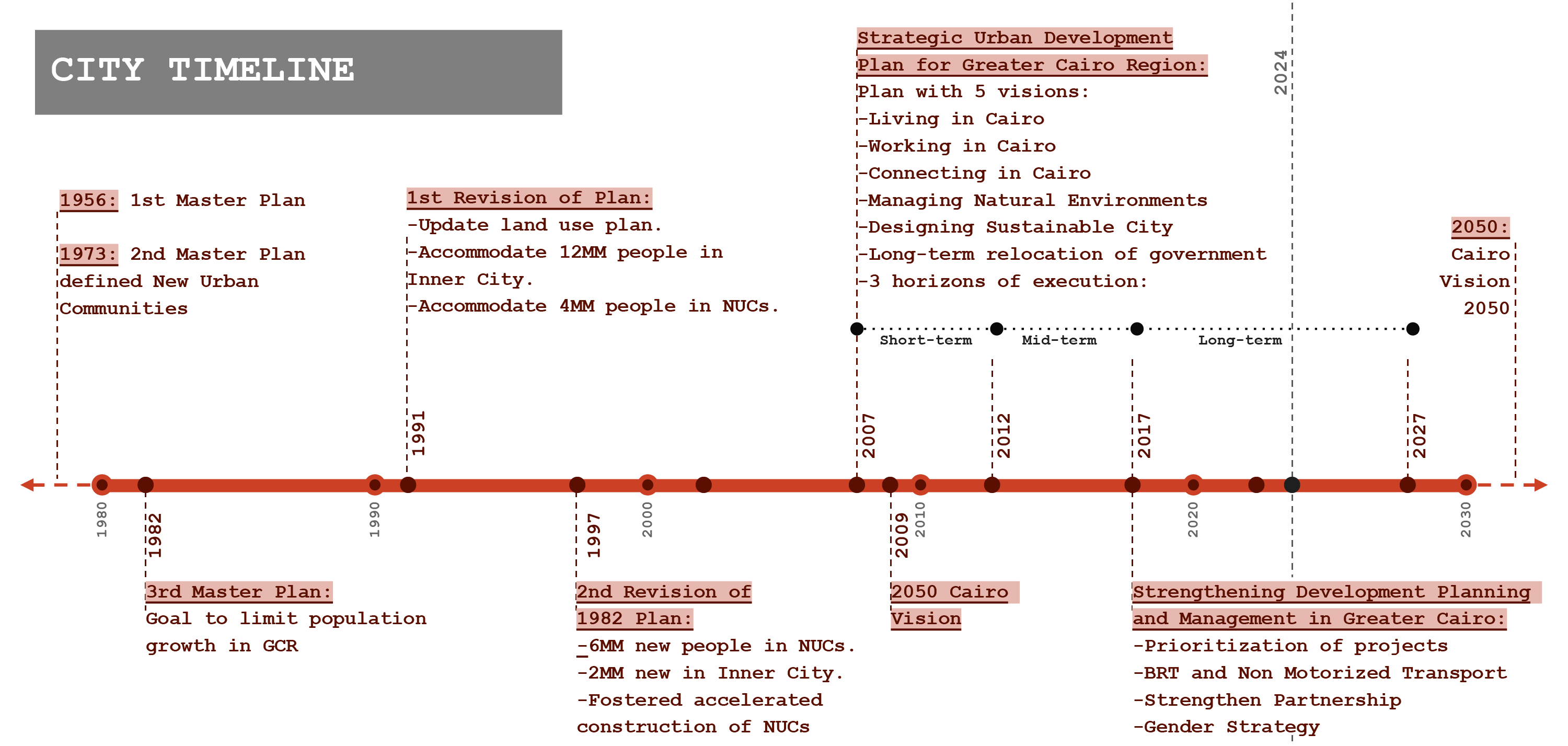

Cairo’s first urban plan dates back to 1956, with subsequent plans focusing on long-term decentralization since the 1970’s. The concept “New Urban Communities” (NUCs) was first coined in the 1973 Master Plan for the city, representing the new Dessert Cities that were to be developed in the periphery of the preexisting Inner Cairo. This decentralization objective: has been a key goal of these plans has been to distribute Cairo’s population and development, alleviating pressure on the inner city.

The current Master Plan of the city was established in 2007 with a short, mid and long-term vision for Cairo for 2027. This includes the ideal of a metropolitan Transport Master plan that would connect the Inner City with the new Dessert Communities. Nevertheless, even since its design it showed a lack of internal communications within the NUCs.

Cairo’s land-use plan emphasizes developing new urban communities (NUCs) like 6th of October City and New Cairo to reduce congestion. However, these desert cities fail to accommodate residents effectively, lacking mixed-use functions and creating inequalities:

- Housing in NUCs is often unaffordable.

- Commuters rely heavily on private vehicles.

- Informal modes of transport fill gaps, underscoring the need for integrated solutions.

This masterplan, as well as all its previous versions were developed and fostered by the General Organization for Physical Planning – GOPP, a national entity. Although it encompasses an integral view of the different Regional Centers and Governorates, it leads to question the role of regional and local entities in the leadership of the metropolitan plans.

By doing a review of the 2007 masterplan, it is possible to identify three (3) main objectives:

- The urgency of developing an inclusive urban development

- The urgency of enhancing housing conditions and ensuring its inclusive for all

- The urgency of developing a sustainable transport network for connecting the entire metropolitan area

These problematics unmask the inequalities behind the differential densification of the city, that materialize as different spatial urban typologies: i) a dense center for the most vulnerable, and ii) car-centric dessert cities for the more wealthy.

Through a of the Sustainable Development Goals, its Targets and Indicators, these issues can be directly linked to four (4) of the targets proposed by the UN Agenda:

- Target 10.2: Promote universal social, economic and political inclusion

- Target 11.1: Ensure safe and affordable housing

- Target 11.2: Ensure affordable and sustainable transport systems

- Target 11.3: Develop an inclusive and sustainable urbanization

Target 11.1: Informal neighborhoods

In Egypt, informal settlements, or “ashwa’iyat,” are urban areas developed without official approval. They typically feature unauthorized construction on agricultural or state-owned land, lack basic infrastructure and services, and have densely populated, poorly constructed buildings. Residents often face legal insecurity, discouraging investment and leading to marginalization. These settlements pose significant challenges for urban planners, necessitating strategies to legalize land tenure, improve infrastructure, and integrate these neighborhoods into Cairo’s urban fabric.

Patterns of Urbanization:

High Urban Density: Cairo’s dense population has led to informal settlements in city centers, highlighting housing and infrastructure challenges.

Target 11.3: Differential Densification

Polycentric Expansion: New cities are being built both within and beyond Cairo’s perimeters. However, many still depend heavily on the inner city, challenging the notion of true polycentrism.

Target 10.2: Differential Housing Price

Social Inclusion: Cairo’s urban development has not sufficiently prioritized social inclusion, leading to disparities in living standards between different areas and communities.

Data availability even shows a biased approach to mapping housing, as it was only available for the eastern part of GCR.

Target 11.2: Transport Accessibility

Localizing SDGs: Worth the Effort?

There is just one target and indicator oriented to measure public transport accessibility. It could be useful to also quantify other externalities such as time spent in private vehicle trips, time spent in congestion, or multimodal character of the transport network.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a global framework, but Cairo’s multifaceted challenges, especially in transportation, indicate that SDGs alone may not address all local needs.

Bottom-Up Approach: Ground Projects

Bottom-Up Actionable Solutions:

Grassroots initiatives, including self-built commercial spaces and community-led projects, contribute to local solutions, though they require support and formal recognition.

Financing Actionable Solutions:

Funding for Cairo’s urban initiatives comes from various sources, including government budgets, international aid, and private investments, which need to be coordinated effectively.

Stakeholders’ Ecosystem for Bottom-Up Solutions:

Collaboration between local businesses, residents, academia, NGOs, and government entities helps to address urban challenges, but this ecosystem needs stronger integration.

Top-Down and Bottom-Up Need Each Other:

Integrating Cairo’s formal and informal mobility systems is crucial for a cohesive transportation strategy, exemplifying how top-down and bottom-up approaches must work together.

Lessons Learned

- SDG Data Collection: Cairo’s urban dynamics require coordinated efforts between local and national entities, with consistent reporting for SDG progress.

- SDGs as Synergy Tools: The SDGs harmonize urban policies, promoting sustainable development in housing, transport, and infrastructure.

- Master Plan as a Citizens’ Platform: Cairo’s master plan offers a platform for citizen engagement and participation to address urban challenges.

- Master Plan Development: The GOPP’s top-down approach develops Cairo’s master plan, with limited representation of informal settlements, needing better inclusion.

- Master Plan Governance: The GOPP governs the master plan, overseeing regional and local institutions.

- Master Plan Impact Evaluation: GOPP evaluates the master plan’s impact, though mechanisms for monitoring relocations and success are unclear.

- Master Plan Flexibility: The plan must adapt to evolving urban challenges, balancing long-term goals with immediate needs.

- New Narratives: Cairo’s development emphasizes balanced growth, sustainable solutions, and integrated approaches.

- Change of Perspective: Cairo’s planning must balance immediate challenges and long-term goals, promoting sustainable growth, social inclusion, and equitable resource distribution.

- Non-affordable Housing: Housing in NUCs is often unattainable for many residents.

- Inequalities in Housing Allocation: Disparities between inner-city and suburban housing reflect inequalities in access and allocation.

- Dependence on Private Transport: Commuters rely heavily on private vehicles to travel between NUCs and the inner city.

- Informal Modes of Public Transport: Informal modes, such as microbuses and tuk-tuks, fill gaps in the formal transport system, yet highlight the need for integrated solutions. The Metropolitan Transportation Plan shows an intention of enhancing public transport, but it does not involve these informal modes of transport that are currently attending the demand that the formal system fails to satisfy.