Reclaiming Mobility and Public Life in the Urban Fabric of Maré

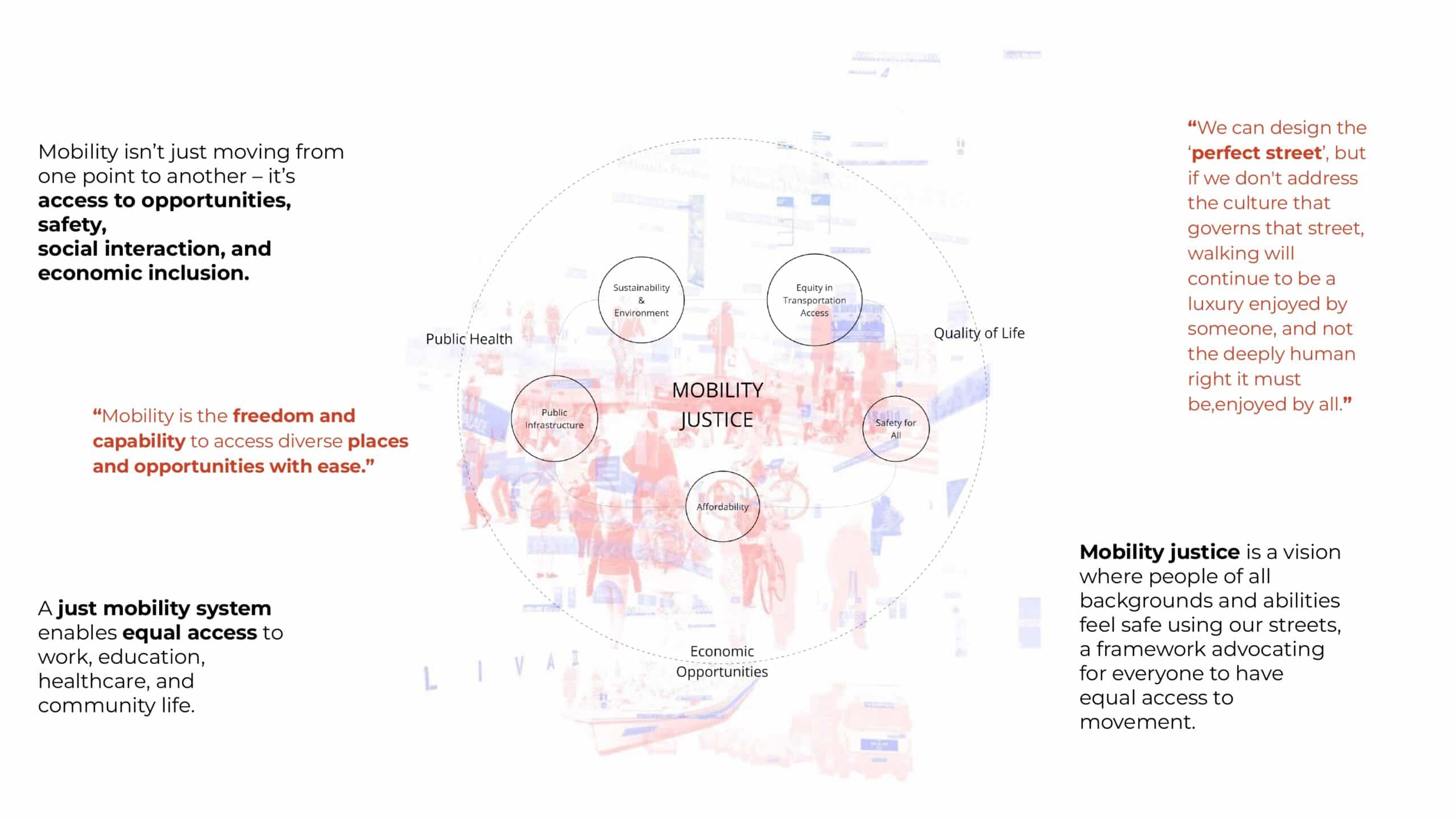

Mobility is not just about infrastructure—it’s about equity, safety, and cultural recognition. In Maré, the challenge was never the lack of roads but the absence of safe, inclusive, and dignified routes for movement. Our approach reframes streets as more than transit corridors—they are spaces of belonging, memory, and community power. By working with the existing dynamics of the territory, we reimagined mobility through the lens of lived experience.

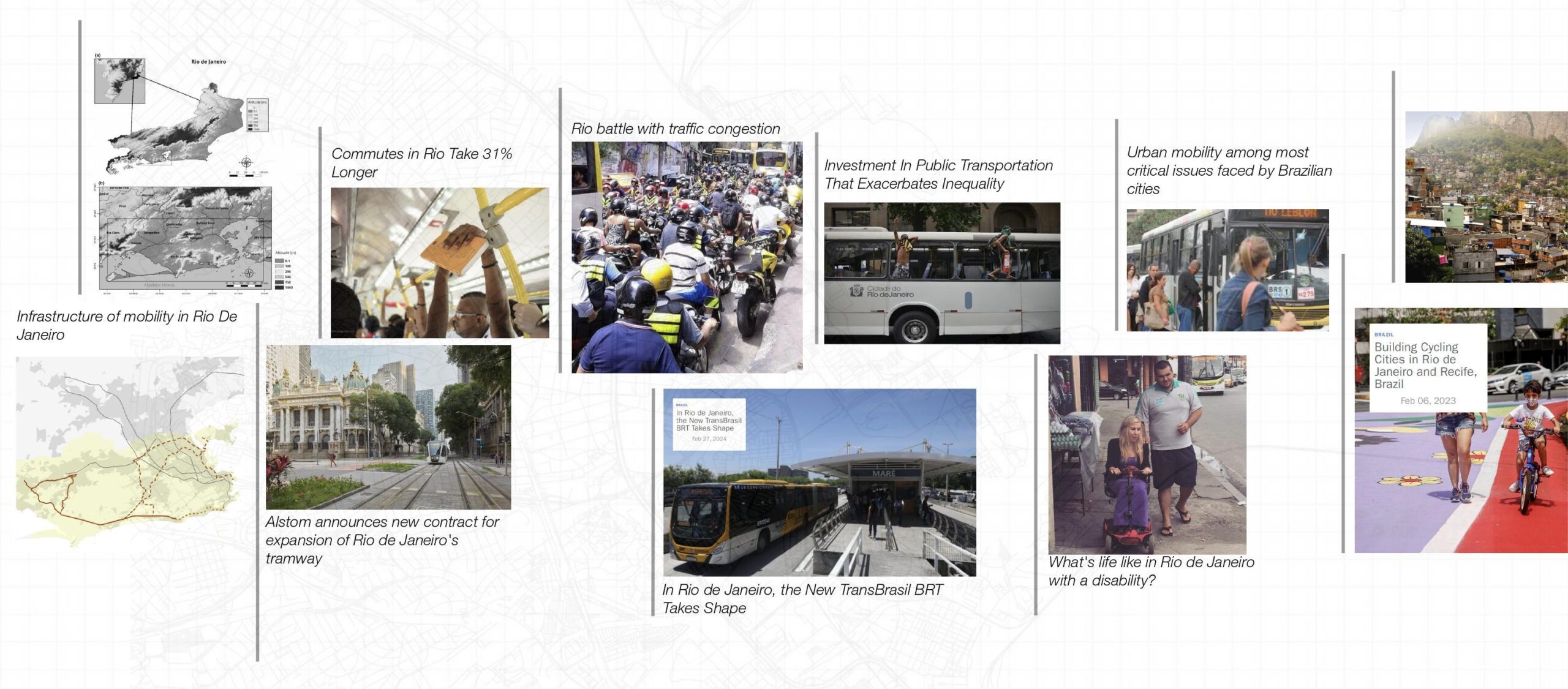

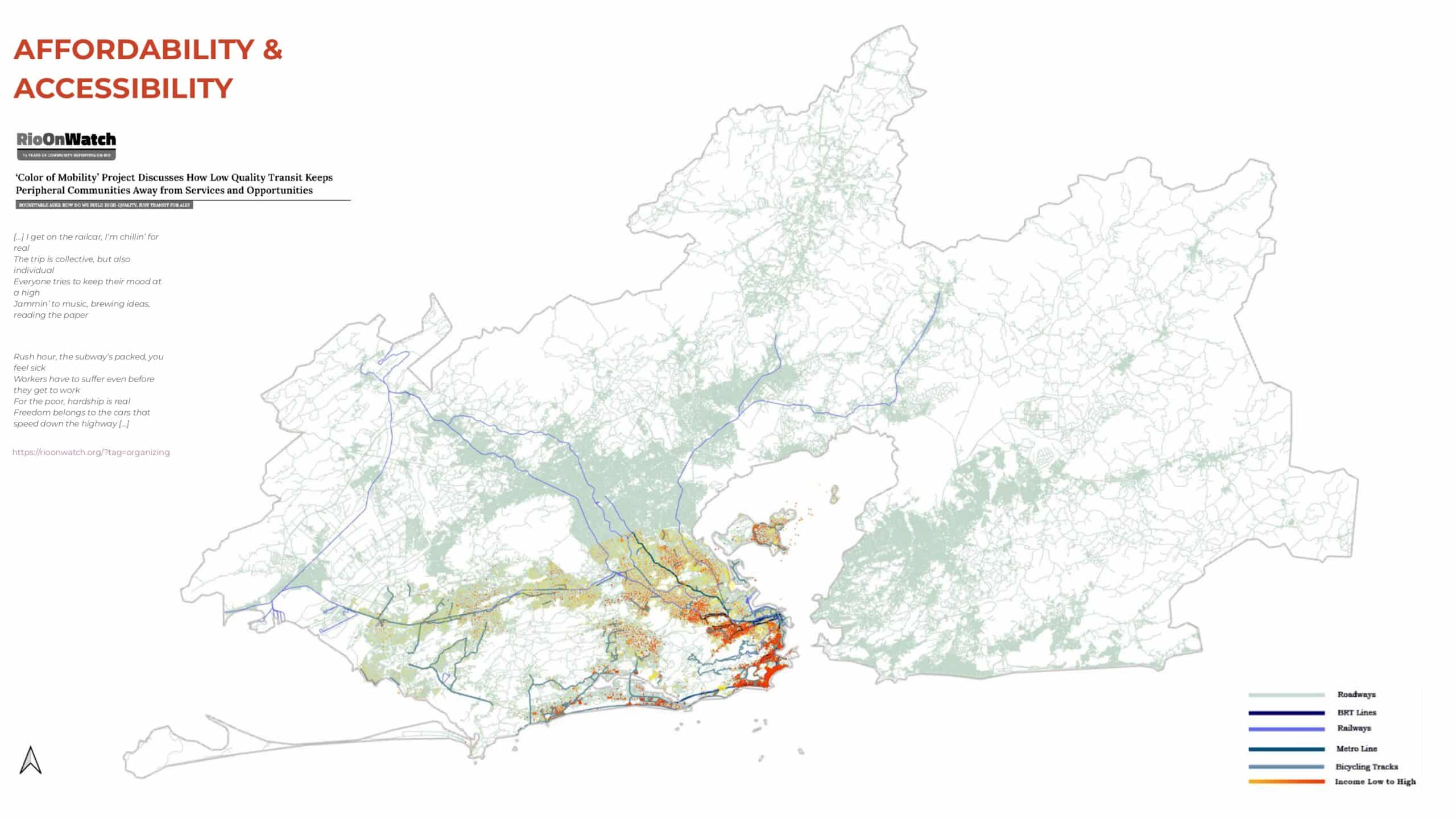

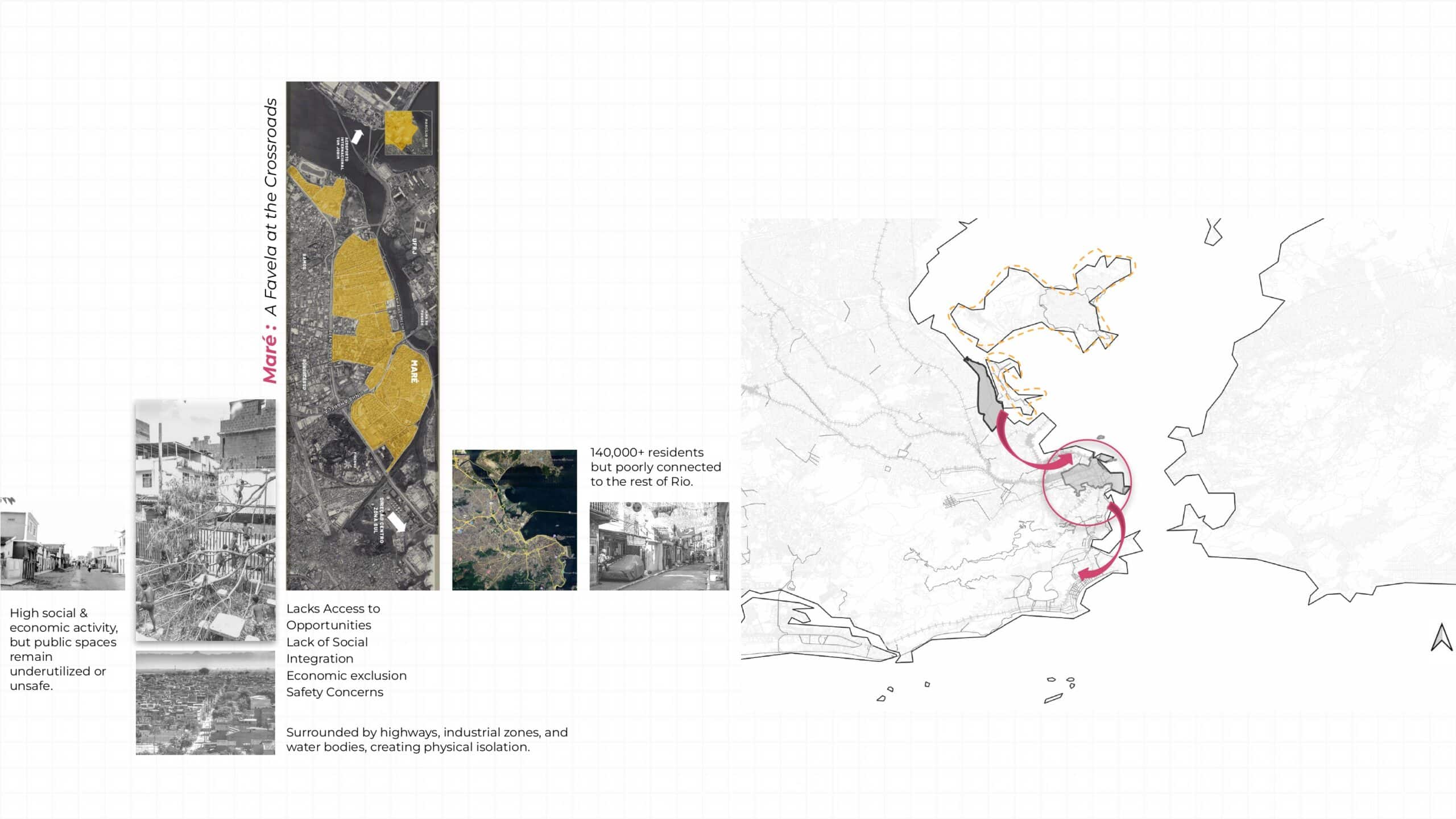

Mobility in Rio de Janeiro is a landscape of stark contrasts—between sleek new transit corridors and neglected informal neighborhoods, between fast cars on expressways and residents walking long, unsafe routes on foot. While the city has invested in projects like the BRT and tram systems, these upgrades rarely reach the peripheries where they’re most needed.

For many, daily commutes are long, expensive, and physically exhausting. Informal solutions, mototaxis, vwalking—fill the gaps left by formal planning. But these systems, though vital, remain unrecognized and unsupported. In Rio, mobility isn’t just unequal—it’s deeply shaped by race, class, and geography. And this inequality isn’t just about how people move—it’s about who is allowed to move with dignity.

Rio faces severe traffic congestion, poor accessibility, and deep mobility inequality.

Public investments like the BRT and tram often exclude informal areas like favelas.

And while much is said about congestion and infrastructure, there’s little conversation about the people who are left out those who wait longer, walk further, and feel unsafe.

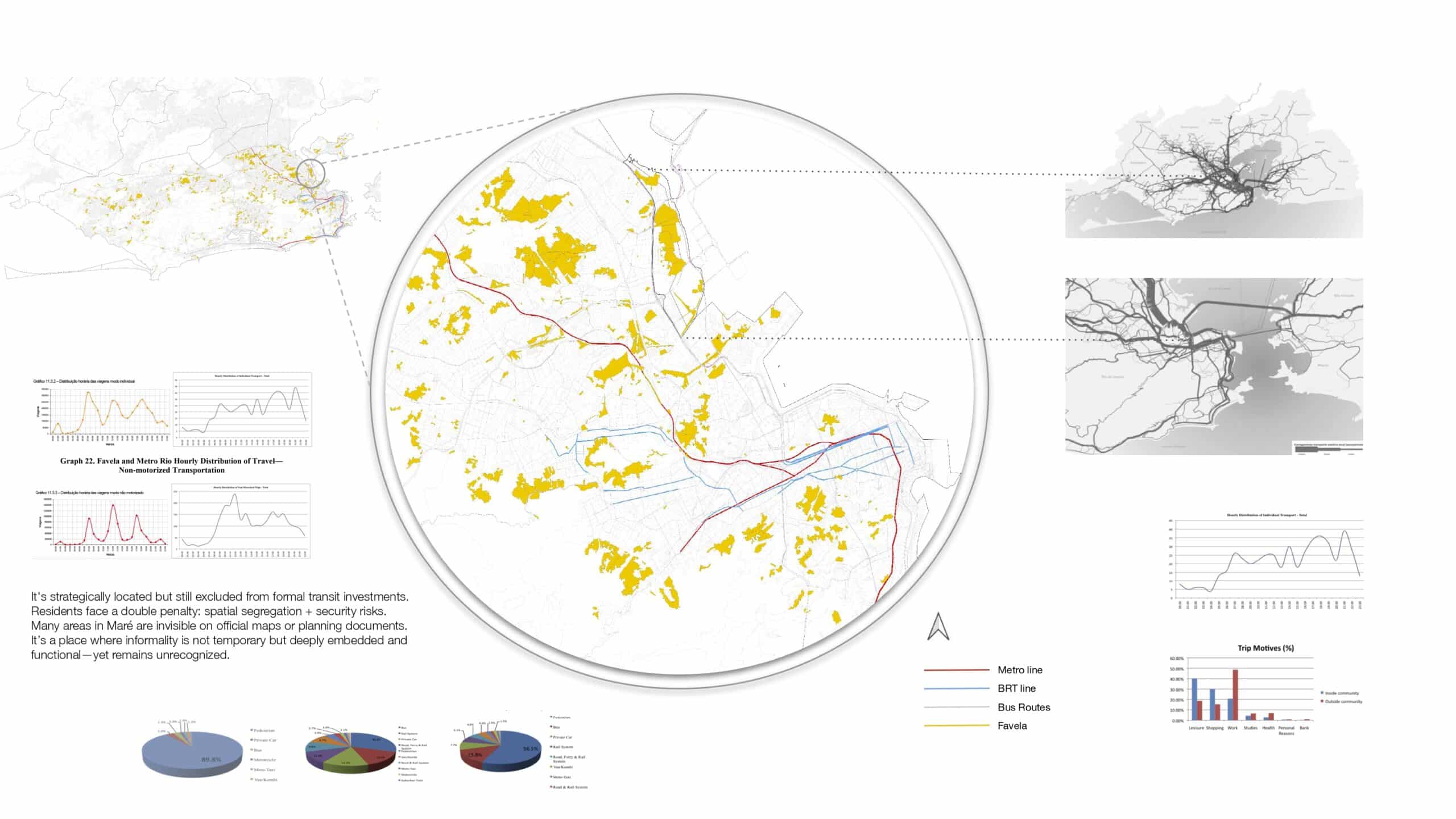

Even though favelas are surrounded by metro and bus routes, they remain disconnected.

In planning documents, many areas—like Maré—are invisible.

This exclusion leads to spatial segregation and insecurity, reinforcing cycles of poverty and marginalization.

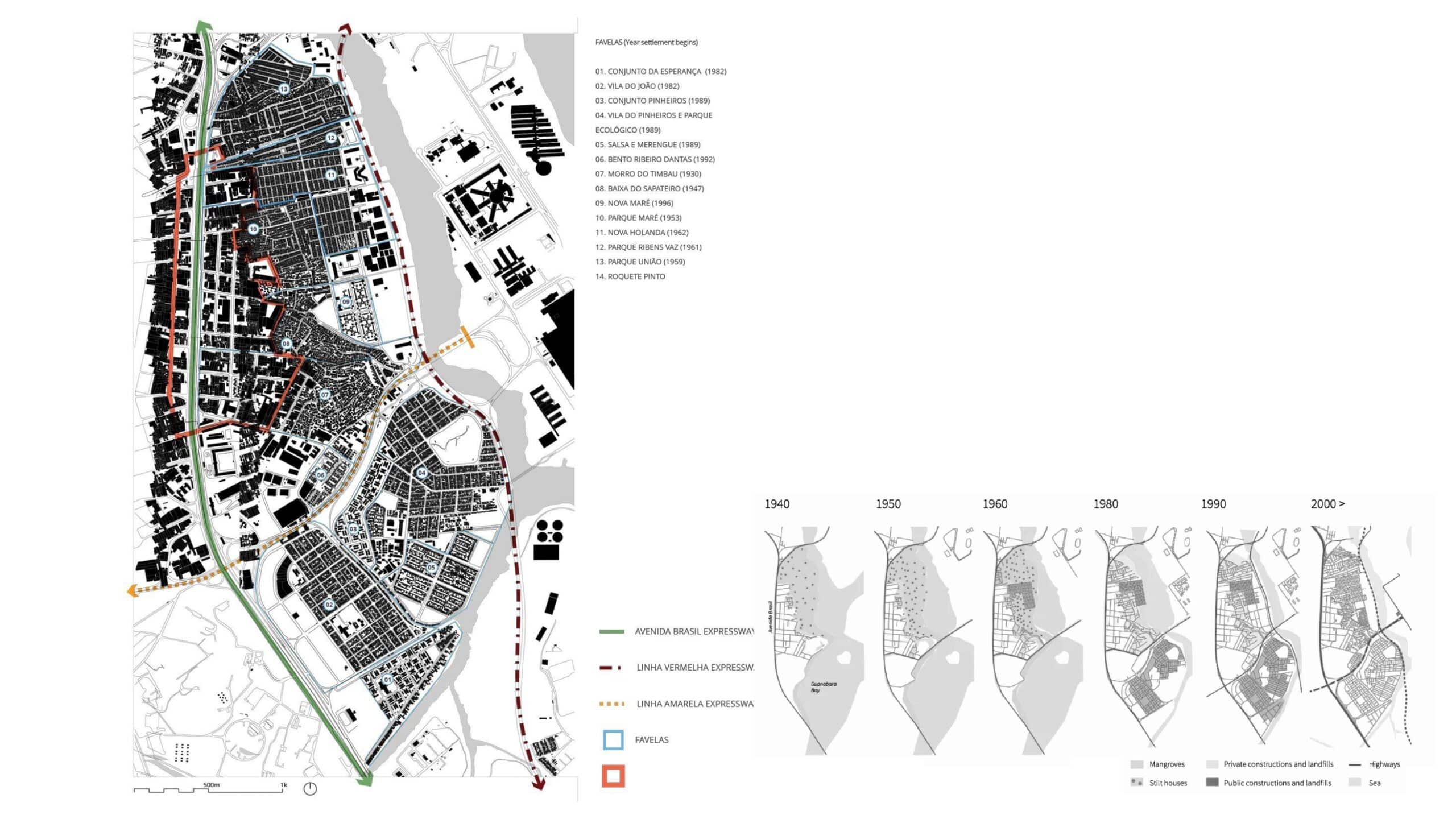

Despite being strategically located at the intersection of key highways and close to formal transit lines, Maré experiences extreme physical and social isolation. Its 140,000+ residents face daily challenges of unsafe streets, long commutes, and unreliable public transport. We chose Maré not only for its scale and complexity, but because it represents so many favelas in Rio—resilient, vibrant, and full of life, yet consistently excluded from urban planning. Addressing mobility in Maré means confronting the structural inequalities of the city, and reimagining streets as tools for justice, connection, and care.

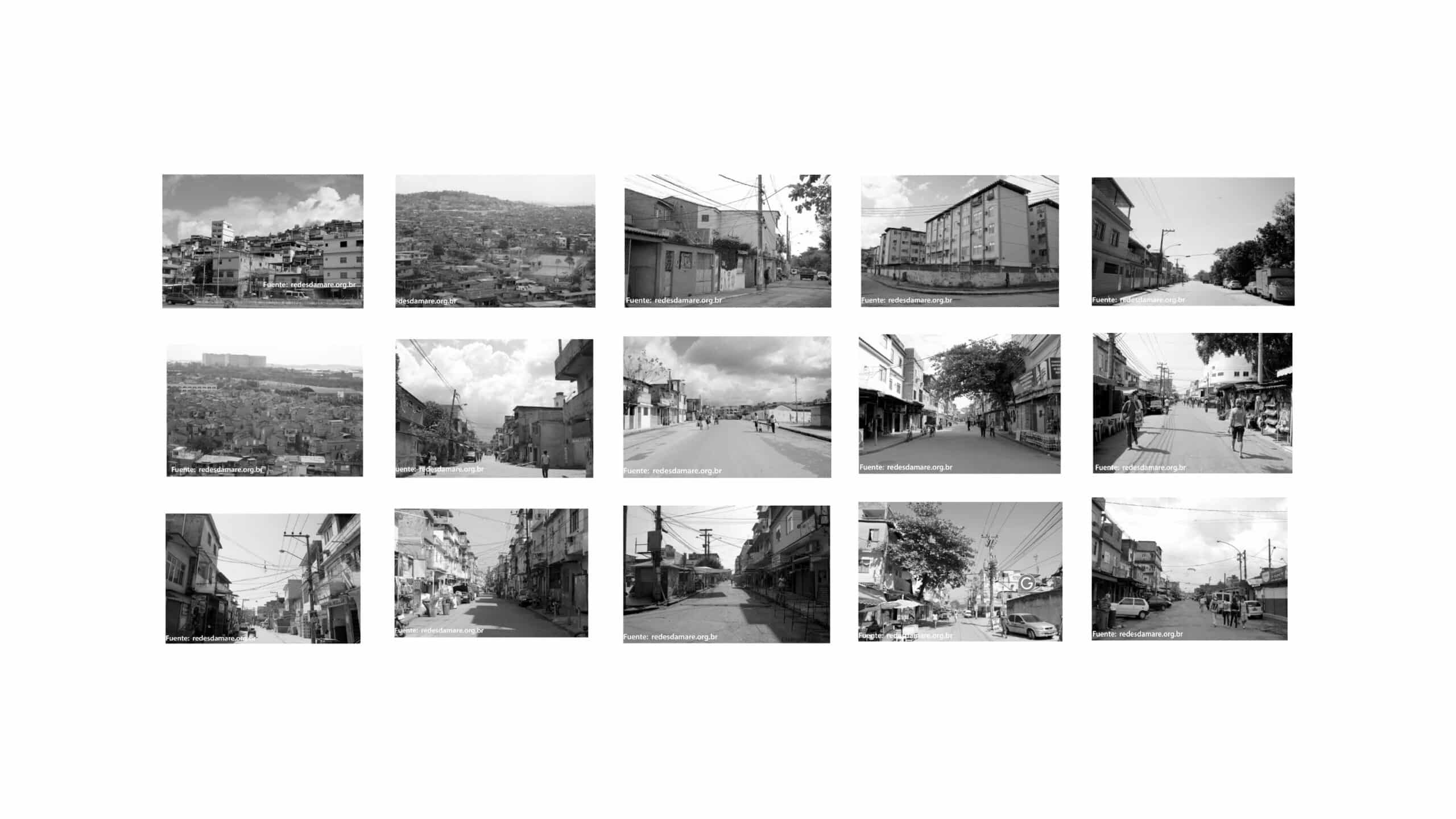

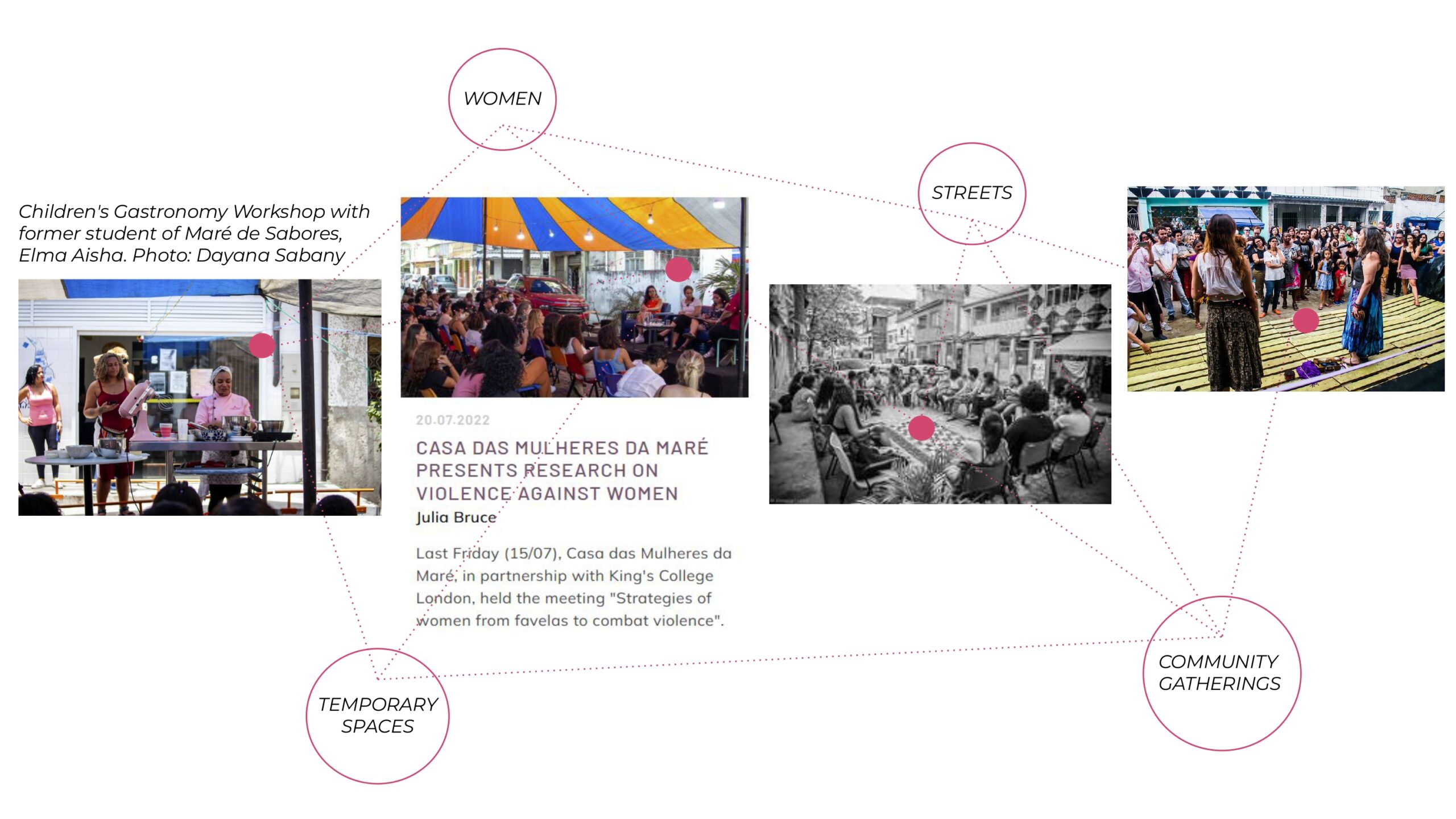

Maré’s people are mostly women, young, and Black or brown. Most have lived here all their lives.

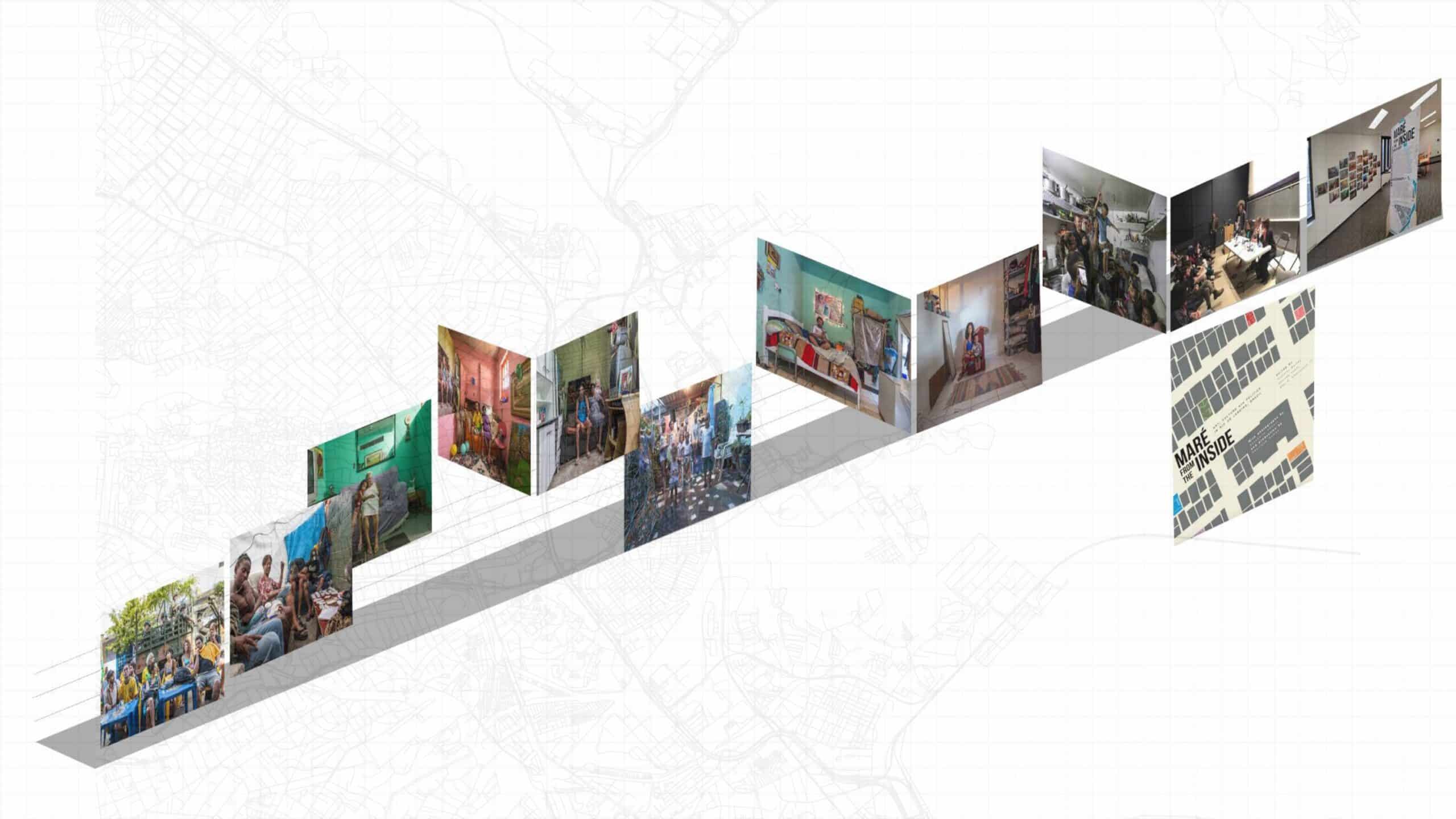

This isn’t a transient community—it’s a rooted one. With local businesses, schools, churches, social programs, and a rich cultural identity.

We’re not designing for ‘users’—we’re designing with and for neighbors, vendors, children, mothers, and elders.

Maré’s streets are shaped by a mix of neglect, informality, and control. Frequent police operations create fear. Infrastructure is poor or absent. But people still occupy the streets. They gather, sell, walk, wait, talk. The question is—can we turn these contested streets into safe, shared spaces of belonging?

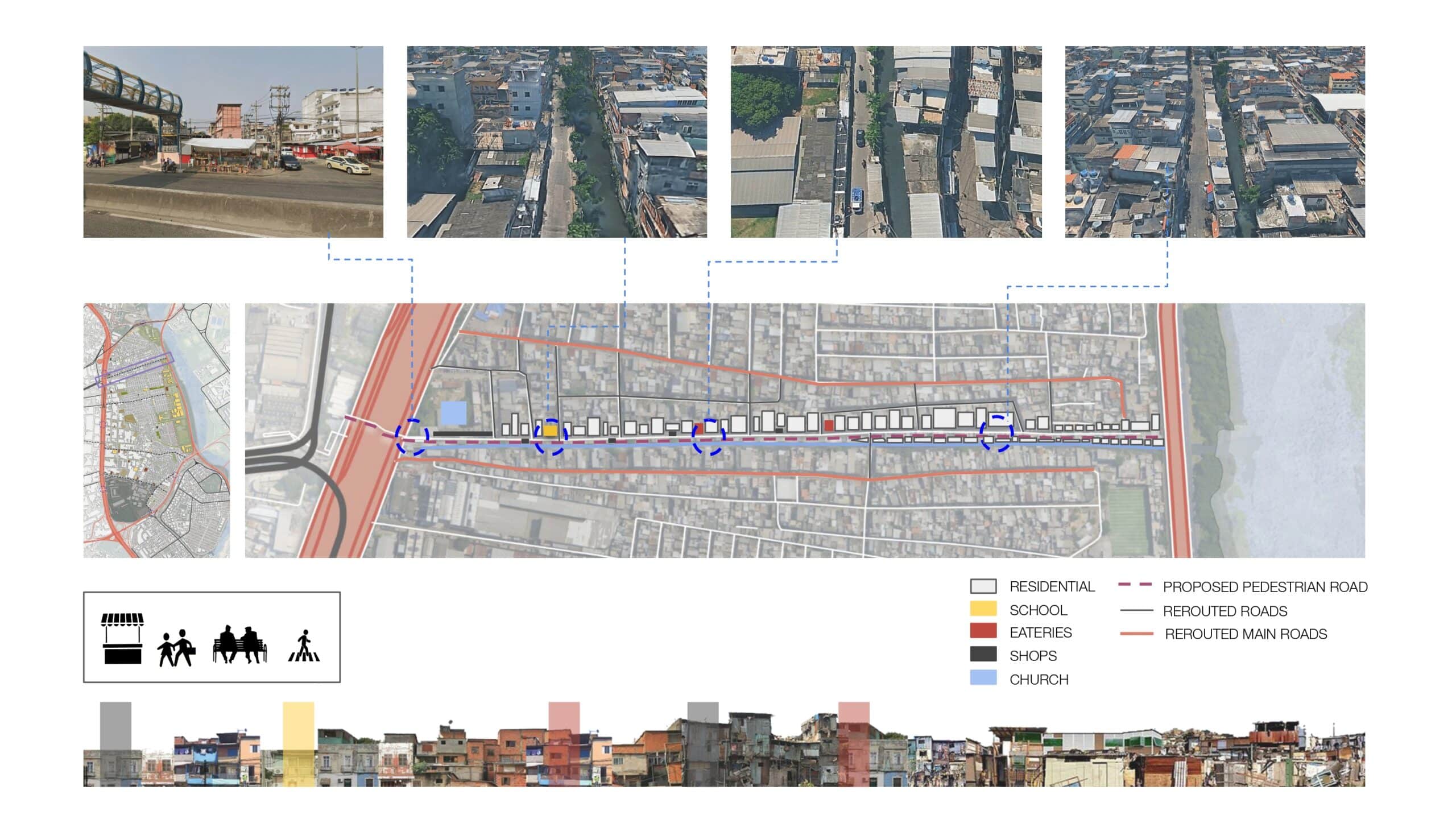

As we moved forward in our design process, we came across a very helpful workshop report conducted by ITDP, which gave us grounded insight into Maré’s public spaces and everyday mobility challenges. This helped us understand how people actually use space and what barriers they face—both physical and social. We considered these findings as key guidance for our interventions. Starting from that, we began to map Maré not just as a block of disconnected favelas, but as a system with incredible potential. We located the major existing infrastructure—BRT stations, schools, churches, NGOs, parks, and underused factory sites—marking them as key points of intervention.

Our goal at the territorial scale is to reconnect Maré with the larger city—creating safe, clear passages to major roads beyond the highways and overcoming the physical barriers that isolate it. At the community scale, we identified the large roads that people already use—and instead of redesigning from scratch, we worked with them. These roads become connectors—shaped by use and programmed through flexible, responsive design. We also proposed to reactivate the edges of these streets—introducing tree cover, lighting, signage, and public seating to enhance safety and comfort. These layers, added over time, shift the character of the street from just movement to meaning.

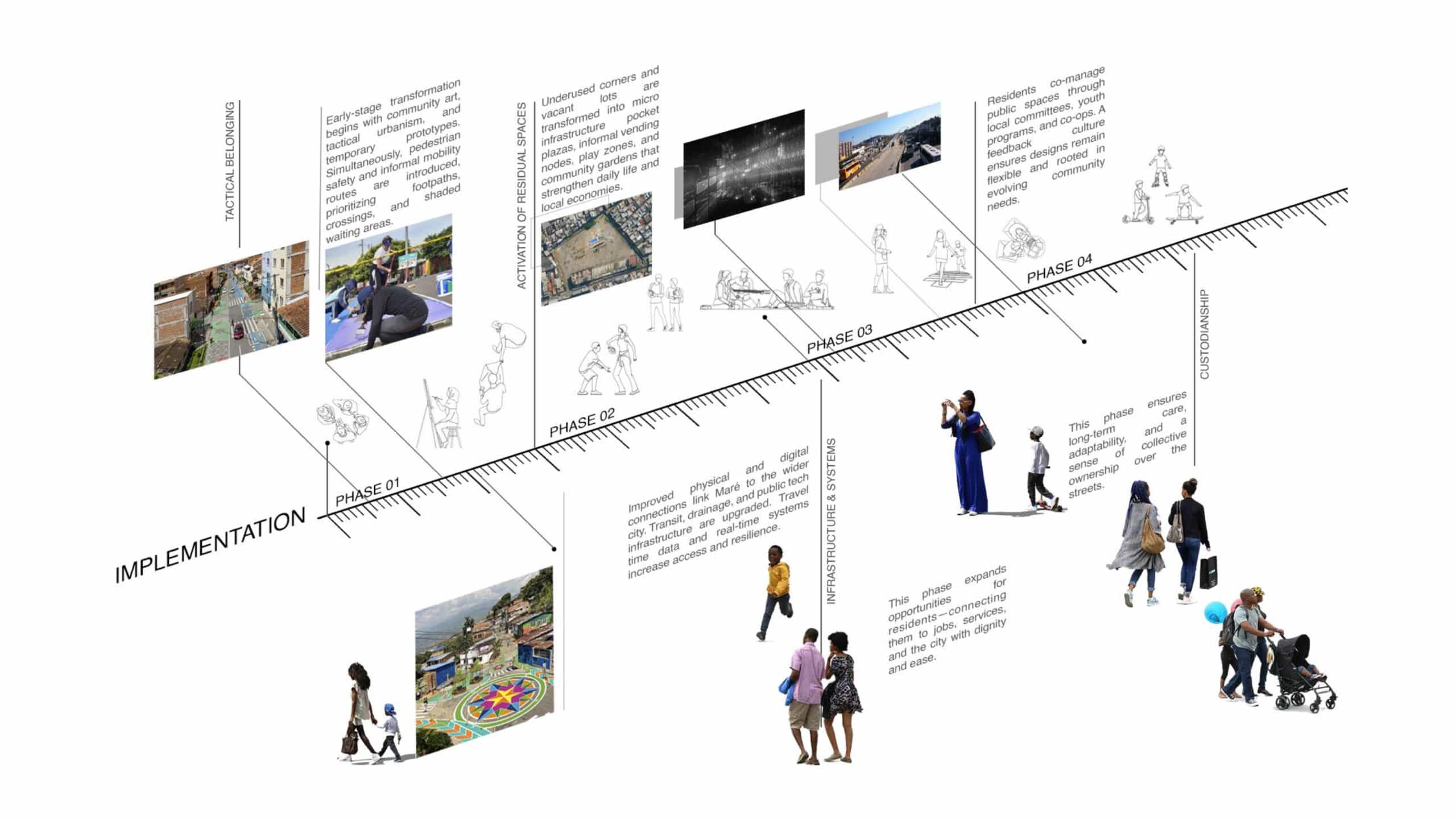

To bring this to life, we broke it down into four clear phases:

- Tactical Phase – where the community takes ownership. Local artists and residents begin by painting lines to define pedestrian zones, adding markings, planting boxes, and collectively deciding where trees, benches, or crossings should be. It’s fast, low-cost, and most importantly—community-led.

- Reactivation Phase – this focuses on transforming residual spaces, such as abandoned plots or canal edges, into active public spaces. These become micro-hubs—hosting everything from markets to learning spaces and cultural events, supporting both economic and social life.

- Infrastructure Phase – here we improve both physical and digital connections—introducing better signage, lighting, slow mobility infrastructure, and improving links between local transport and city-wide networks.

- Custodianship Phase – the long-term vision where residents co-manage these public spaces through youth programs, community workshops, and local caretaking groups. It’s about ensuring the changes are not just implemented—but sustained.

In our zoomed-in site, we focused on a canal-side street, which today faces many issues—poor sanitation, no proper walking space, no seating, and an overall sense of neglect.

But this street is surrounded by key everyday functions: a school, a mall, restaurants, kiosks, shops—it’s full of potential.

We began by identifying the ‘heartbeat’ of the place—what’s already happening here. In the next image, you’ll see how we imagine the tactical phase beginning: people marking safe paths, drawing lines, planting boxes, and reclaiming the street from its current harshness.

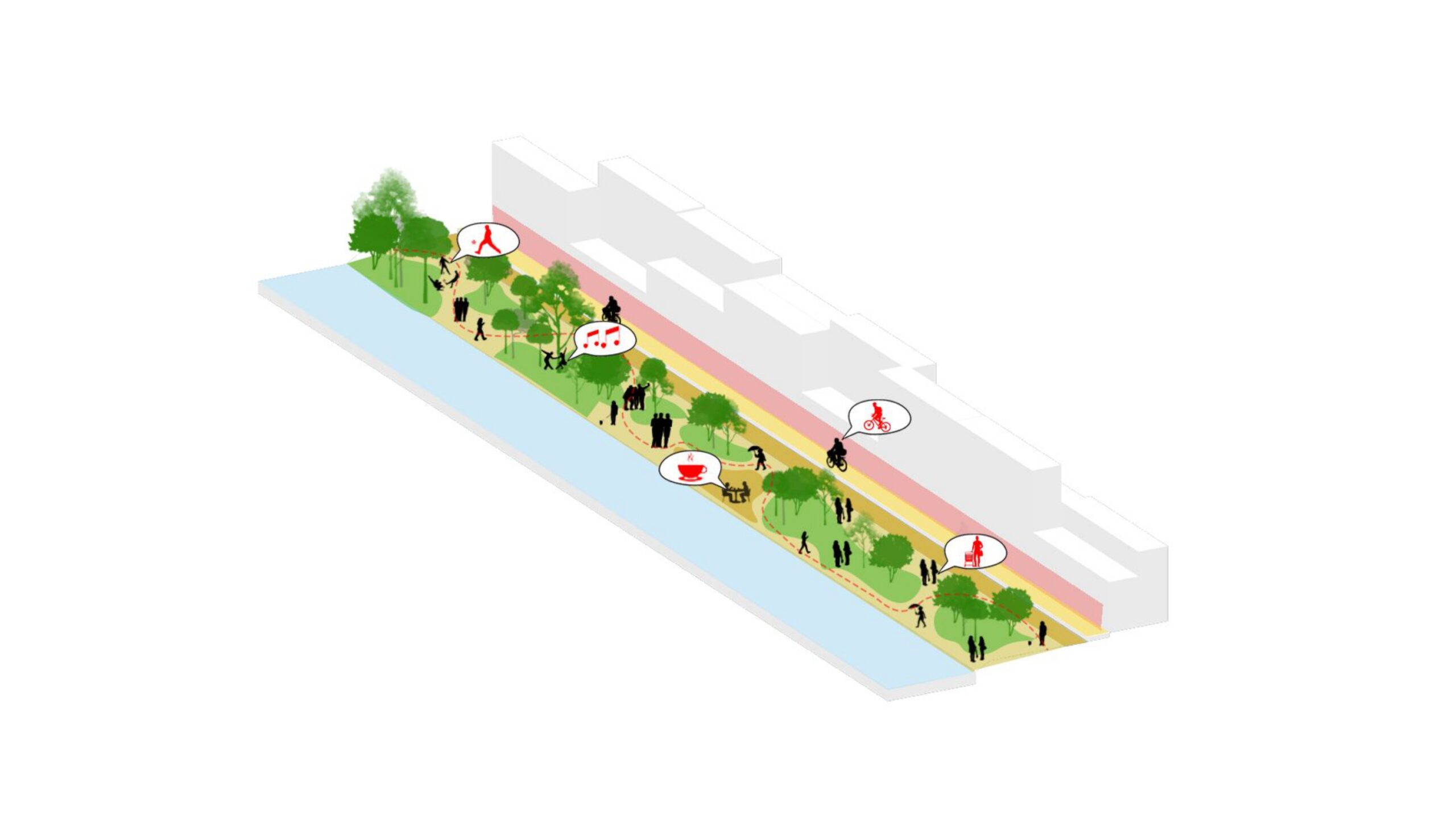

As the process evolves, infrastructure slowly starts to appear—better paving, lighting, trees, shaded spaces, flexible kiosks. And over time, this street can host markets, outdoor classrooms, play areas, or seating zones—based on the community’s evolving needs.

What emerges is a layered vision for the future: where youth programs manage public spaces, women feel safe walking at night, and informal vendors become integral to the public realm. The street transforms from a space of fear to a space of care. By working across territorial and community scales, we aim to create a mobility network that doesn’t just connect people physically—but reconnects them socially, economically, and emotionally.

This is the future we imagine: A street where a child can safely walk to school. A grandmother can sit under a tree while waiting. A local vendor can sell without fear. Where people stop to talk, rest, perform, or celebrate. These renders show how a once-disconnected, unsafe space becomes an artery of belonging—stitched into the larger vision of the masterplan: Intermodal hubs that integrate formal and informal transit; Residual space reprogramming; A local economy powered by street life; A network of streets that center care, culture, and safety.

This is Streets of Belonging—and it starts with the people who walk them every day.