Mapping women+ safety through visibility

Introduction

Delhi, like many global cities, presents a paradox for women+ navigating its public spaces: a landscape where visibility can feel both protective and precarious. According to the National Crime Records Bureau (2022), over 14,000 crimes against women were reported in Delhi alone. Yet statistics only scratch the surface of a deeper, more complex urban condition—where perceptions of safety, not just incidence, governs women+’s freedom of movement.

This research investigates the perception of safety among women+ in Delhi, arguing that safety cannot be understood solely through crime data or infrastructure. Instead, it must be explored as a subjective, situated, and collective experience. Grounded in empirical evidence—ranging from surveys and interviews to video diaries and social media interactions, the study listens closely to women+’s lived realities: the fear of walking alone at night, the comfort of a well-lit street, or the quiet panic of crowded public transport.

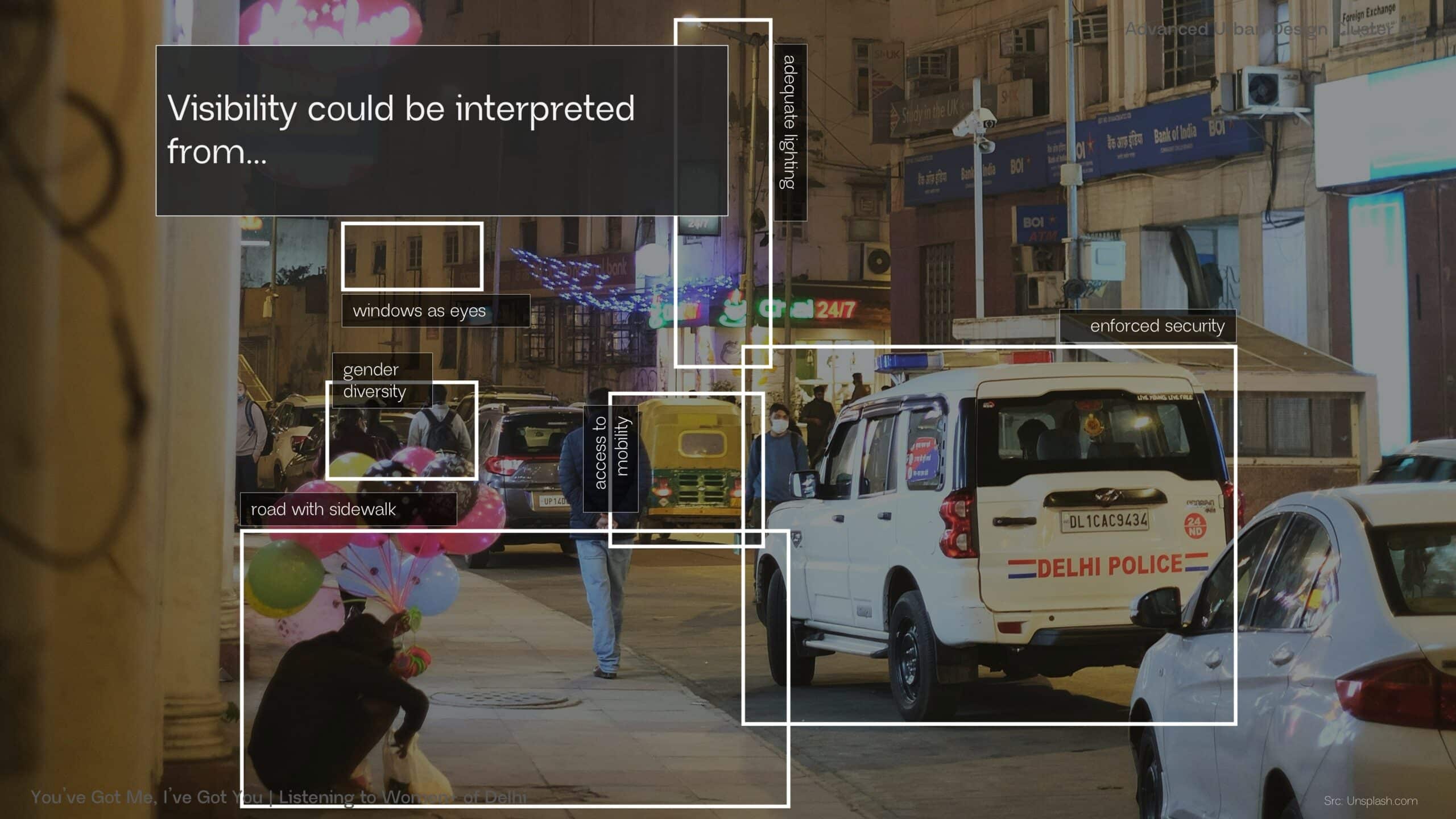

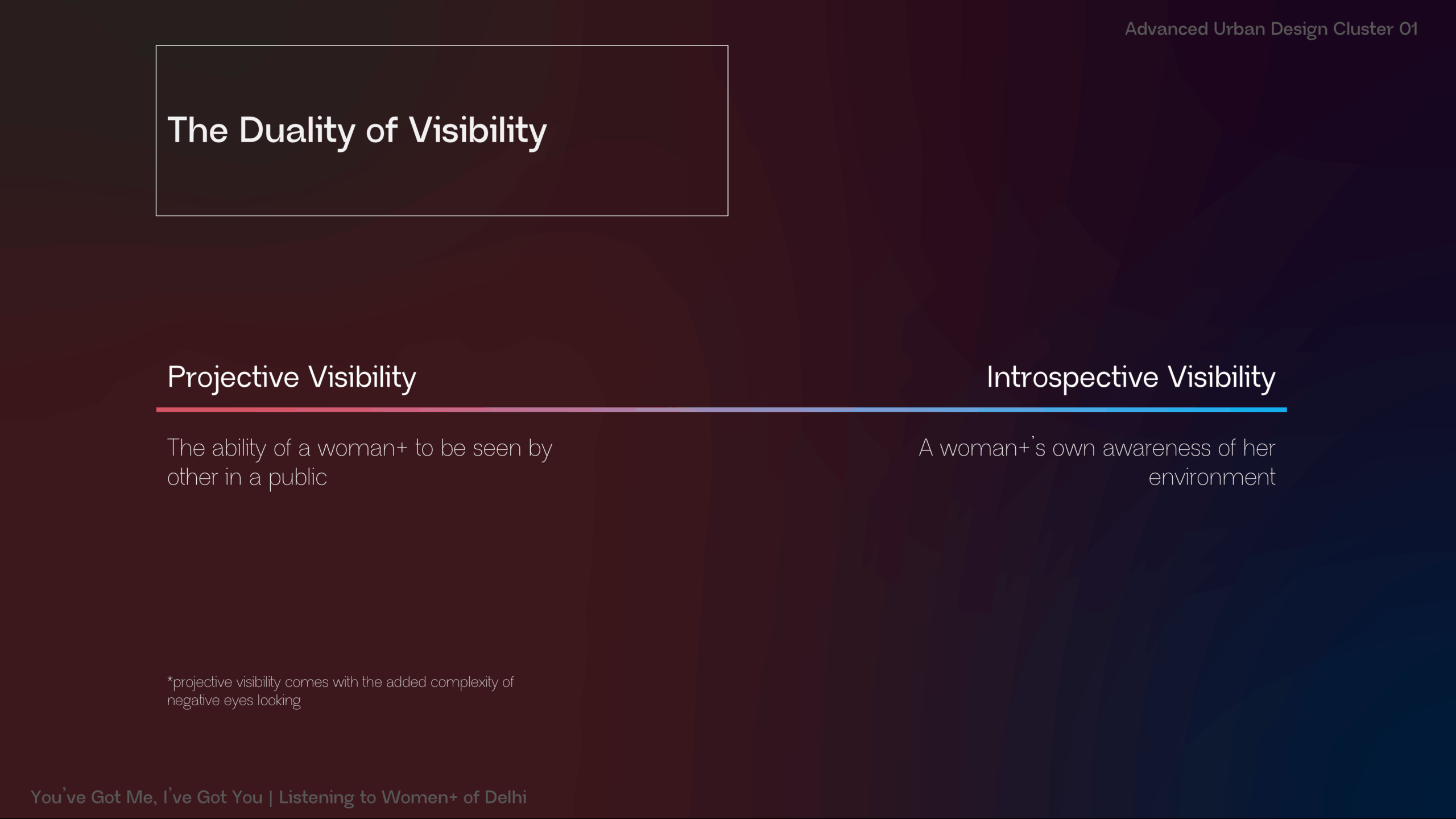

Spatial factors such as lighting, openness, people density and visibility emerge as recurring themes in shaping these perceptions. However, the research goes further to dissect the duality of visibility as both “projective” (being seen by others) and “introspective” (one’s own awareness of surroundings). This distinction becomes especially critical in understanding how women+ assess risk and safety not just reactively, but intuitively and contextually.

Through spatial mapping and qualitative assessment of key urban zones, the research highlights the limitations of existing safety audits, such as those by Safetipin, which, while rigorous, often fail to account for the emotional and communal dimensions of safety. In contrast, this study emphasizes how community presence and social legibility, what Jane Jacobs once described as “eyes on the street”, serve as intangible yet vital components of safety perceptions.

By centring women+’s voices, the study reclaims safety as a relational, embodied, and everyday urban right that is co-constructed, constantly negotiated, and deeply tied to the right to visibility, mobility, and community presence.

Research Question

Ultimately the research asks many questions, but the key research question is:

How can the evaluation of designed public spaces [through the lens of women+ safety perceptions] in Delhi, inform urban strategies that support their free and confident movement through the city?

This raises of series of sub-questions which are researched and answered in a sequence of 3 chapters.

Sub-Research Questions

- What urban characteristics most significantly influence women+ perceptions of safety in Delhi, and how do these factors impact their mobility and spatial agency?

- How can the tacit knowledge and everyday navigational choices of women+ in Delhi be surfaced and leveraged to restore their agency in urban mobility?

- What models of community-based navigation and support can enhance safety for women+ in Delhi, and how can such systems be designed to offer personalized, trust-based safety optioneering?

Chapter 01: Reading Delhi

identify key spatial factors that shape women+ sense of safety

On December 16, 2012, India witnessed one of the most heinous and shocking crimes against a young woman in Delhi. Nirbhaya—a name given to protect her identity—was a 23-year-old physiotherapy trainee who was brutally gang-raped and mutilated by six men in a moving bus before being thrown, severely injured, onto the streets of South Delhi. This incident had a nationwide impact, triggering both positive and negative societal shifts. On one hand, it led to a surge in reports of sexual harassment and gender-based crimes, as more women+ came forward to share their experiences. On the other hand, it intensified fear among women+, further restricting their freedom in urban spaces. Many began avoiding public spaces after dark, becoming hyper-aware of their surroundings while navigating the city. While similar crimes had occurred before—and continue to occur—this case became a turning point in conversations around women+ safety, reshaping how public spaces are perceived and experienced by women+ across India.

Alarming crime drifts in Delhi

India currently has 19 metropolitan cities, where most crime data related to women+ is recorded. These cities also report a higher number of complaints filed by women+ against offenders. Such complaints fall under the category of Crimes Against Women, as defined by the two primary legal frameworks governing criminal offenses: the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and Special and Local Laws (SLL).

Comptroller and Auditor General of India defines this as “[Crimes against women] includes any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life.“ According to these laws, while women+ can be victims of general crimes, this category specifically addresses offenses that target and defame women+.

Through this research and data available in the National Crime Records Bureau(NCRB), the number of reported cases across various subcategories of crimes against women+ in India’s top 5 metropolitan cities, have highlighted how women+ are not safe even the most developed cities of the country. Among them, Delhi stands out with an alarmingly high number of cases, making it a critical focus of this research. Between 2020 and 2022, 37,922 cases were reported in the capital alone. Delhi, the capital of India, has a projected population of 7.5 million spread across 700 km², resulting in a population density of approximately 10,700 people per km². Women+ make up roughly 46.27% of this population. As mentioned earlier, crimes against women+ in Delhi have reached alarming levels. From 2020 to the end of 2022, reported cases steadily increased, with the crime rate against women+ reaching approximately 400 per 100,000 women in 2022.

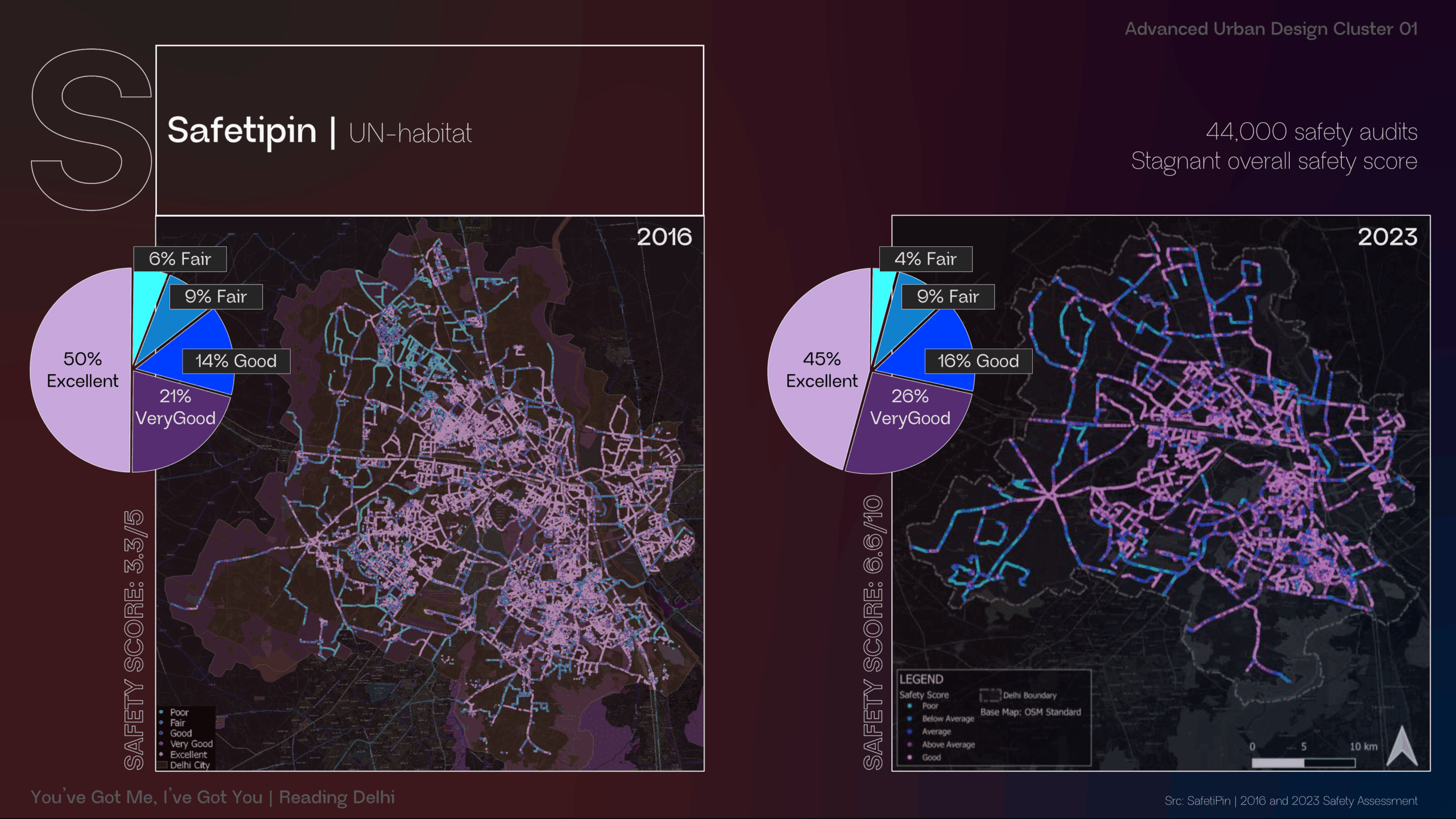

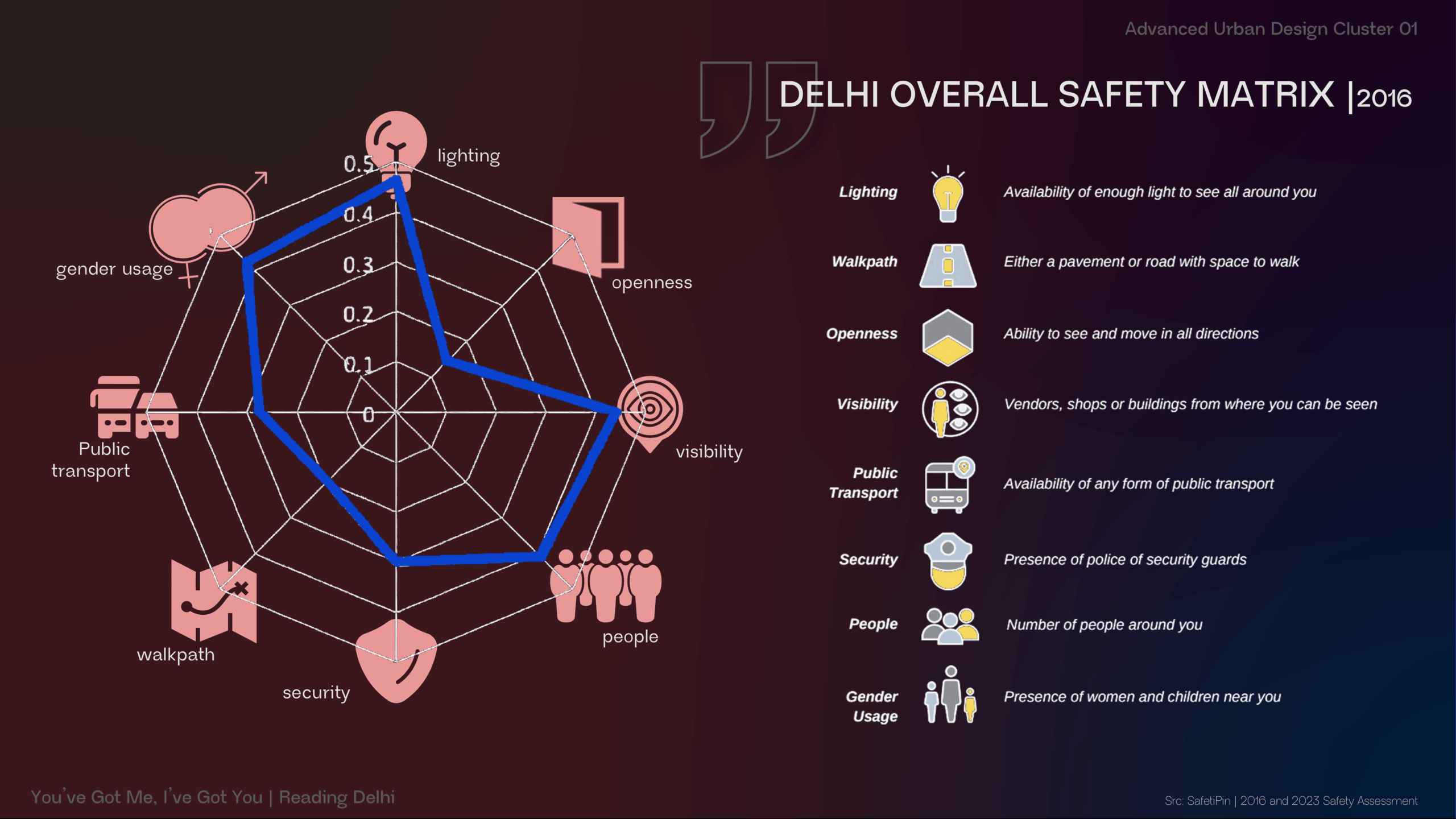

SafetiPin is a mobile app and urban technology platform developed to support safer and more inclusive cities by collecting and analysing data on the perception of safety in public spaces, especially for women and marginalized communities. Originally initiated in India and now used in over 65 cities globally, SafetiPin was developed in collaboration with organizations like UN-Habitat to integrate crowdsourced data into urban planning processes.

Delhi has been one of the key case study cities for SafetiPin, with approximately 44,000 safety audits conducted between 2016 and 2023. In 2016, Delhi received an overall safety score of 3.3 out of 5. By 2023, the score was reported as 6.6 out of 10. While this might initially suggest progress, a closer examination reveals that the overall safety in the city has remained largely stagnant over the seven-year period—the score essentially plateaued, not improved.

More critically, a deeper analysis of the data reveals a decline in the number of areas rated as ‘excellent’ in safety. Rather than expanding safe zones, the city has seen a contraction of high-rated public spaces, signaling a concerning erosion in quality, even if the average appears stable. This stagnation and decline in top-tier safety indicators underscore the limited effectiveness of existing safety interventions, and point to the need for new, community-driven approaches that go beyond infrastructure and policing to address the nuanced, lived realities of urban insecurity.

SafetiPin’s safety audits are structured around eight core parameters, developed to offer a global, comparable understanding of urban safety, particularly for women+. While these metrics serve as a strong baseline across cities, their interpretation—and relevance—must be contextualized to each urban setting. In the case of Delhi, a city marked by stark spatial and social contrasts, these parameters offer useful insights, but also reveal important limitations when divorced from lived experience.

While these parameters help quantify and map safety, they remain surface-level unless grounded in context. In Delhi, the nuances of caste, class, time of day, and social norms heavily influence how these indicators are perceived. Moreover, these eight parameters, though standardized, do not fully capture emotional, communal, or temporal experiences of (un)safety—a gap this research seeks to address through deeper listening, mapping, and collective narration of women+’s urban experiences.

Chapter 02: Listening to Women+ of Delhi

understand and utilize women+’s lived experiences to inform safer and more autonomous urban navigation

To address the limitations of standardized safety metrics and capture the subjective, emotional, and contextual layers of urban insecurity experienced by women+, an empirical research process was carried out as a core part of this study. Recognizing that parameters like lighting or security alone cannot account for how women+ actually feel and navigate spaces, the research prioritized methods that foreground lived experience and personal narratives.

The study employed a mixed-methods approach, which included surveys, video diaries, Instagram-based interactions, and semi-structured interviews. Each method was designed to elicit different facets of perception. The surveys helped quantify common triggers and safety indicators, while video diaries captured the immediate, embodied experiences of moving through the city. Instagram interactions provided a platform for informal and candid expressions, particularly among younger participants, and the interviews allowed for deeper reflection on personal and collective understandings of safety.

Together, these methods offered a layered, grounded, and diverse account of what it means to feel safe or unsafe as a woman+ in Delhi. They also revealed critical insights that are often missed in conventional audits, such as the role of emotional memory, body language, or the presence of other women as markers of comfort and confidence in public space. These rich, qualitative accounts not only challenged the adequacy of existing safety audits but also propelled the research forward. Two pivotal questions formed the backbone of this inquiry:

- “What do you avoid when you are outside for your safety?”

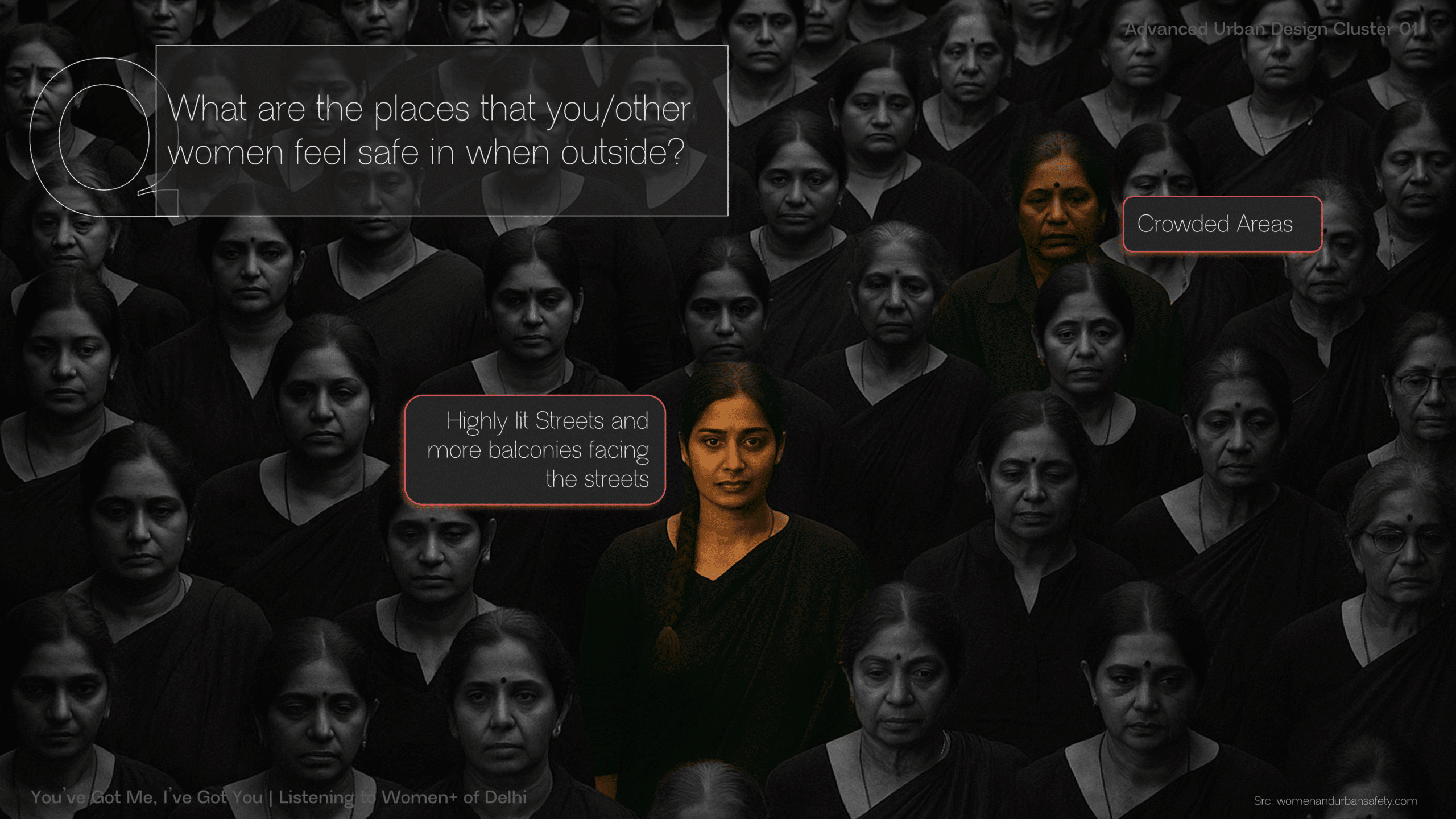

- “What are the places where you or other women feel safe when outside?”

The responses to these questions were striking in both their clarity and emotional weight. Women+ spoke of lonely stretches, poorly lit sidewalks along wide roads, and waiting outside metro stations at night as spaces they actively avoid—highlighting the interplay between physical form and social abandonment. Conversely, spaces perceived as safe were often not defined solely by design, but by their social life: crowded areas, well-lit streets, and locations with balconies or shops facing the street. These responses emphasized that safety is not just about infrastructure, but about visibility, presence, and relational awareness.

Crucially, this feedback underscored that women+ assess safety not in binary terms, but through a complex layering of spatial cues, people dynamics, and intuitive judgment. These lived insights have shaped the direction of the research, reinforcing the need for an approach that values situated knowledge and community perception as valid urban data. By centering these responses, the study moves beyond abstraction and toward a more empathetic, participatory, and feminist reading of the city.

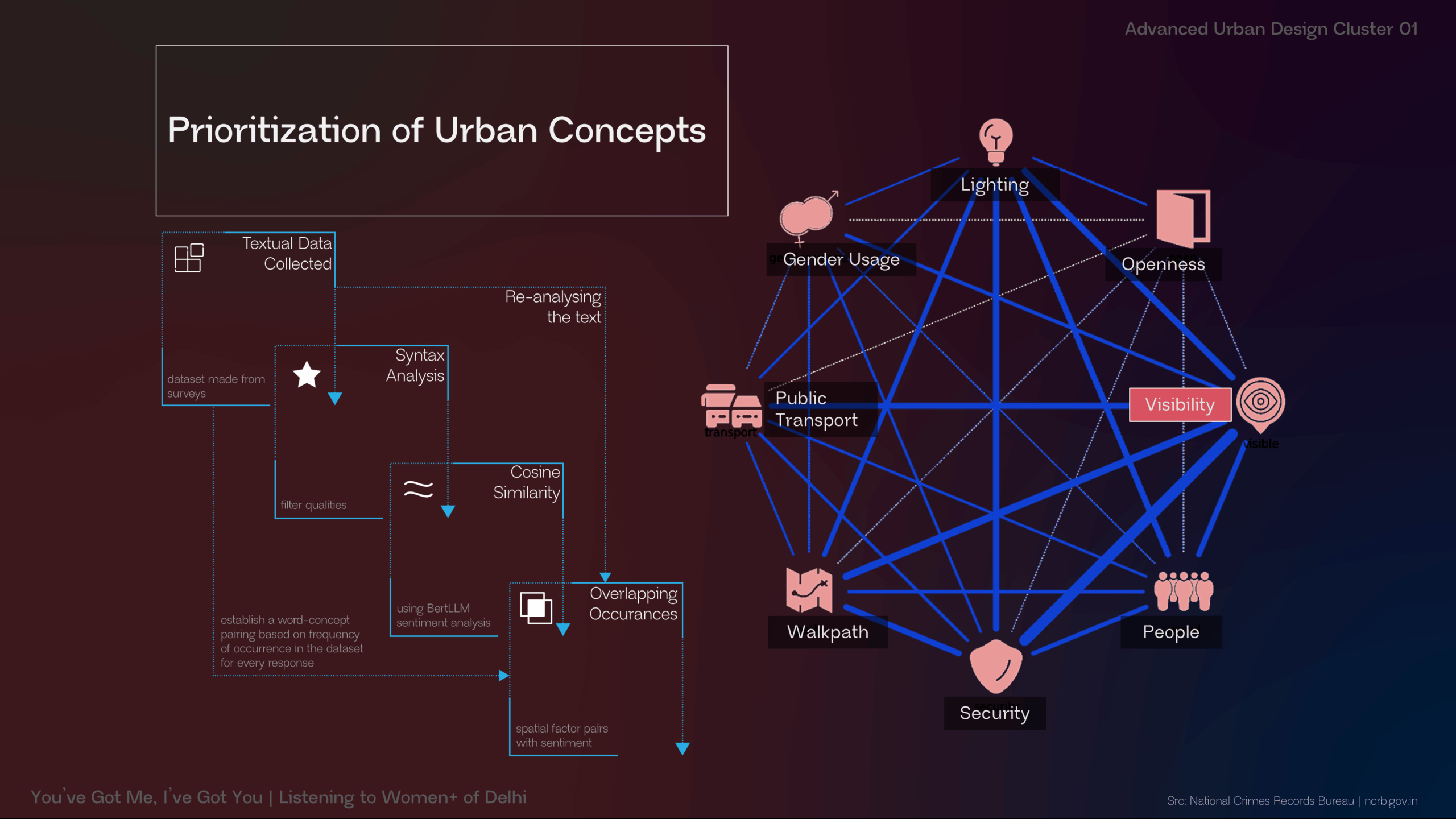

To translate the depth of qualitative responses into a structured, analyzable format, a prioritization methodology was developed. This methodology was designed to extract quantitative insight from qualitative data, allowing recurring patterns, perceptions, and spatial associations to be measured with greater clarity. Leveraging advanced natural language processing techniques—including syntax analysis, BERT-based large language models, and cosine similarity scoring—the research systematically evaluated how often and in what context the eight SafetiPin parameters emerged in participants’ narratives.

The objective of this methodology was to identify which urban concepts most significantly influence women+’s perception of safety in Delhi. By mapping the frequency and semantic proximity of key terms across all data sets—surveys, interviews, video diaries, and social media interactions—the analysis revealed a clear and consistent outcome: Visibility emerged as the most critical concept driving the sense of safety among women+ in the city.

Moreover, visibility did not exist in isolation. The data showed that it frequently co-occurred with other parameters such as lighting, people density, and gender usage, reinforcing the idea that visibility is both a spatial and social construct. It became evident that spaces where women+ felt seen—not surveilled, but socially acknowledged—offered a deeper sense of comfort, confidence, and legitimacy in public life.

This data-driven insight validated and deepened the qualitative findings, positioning visibility as a central pillar in understanding and reimagining urban safety from the perspective of women+ in Delhi.

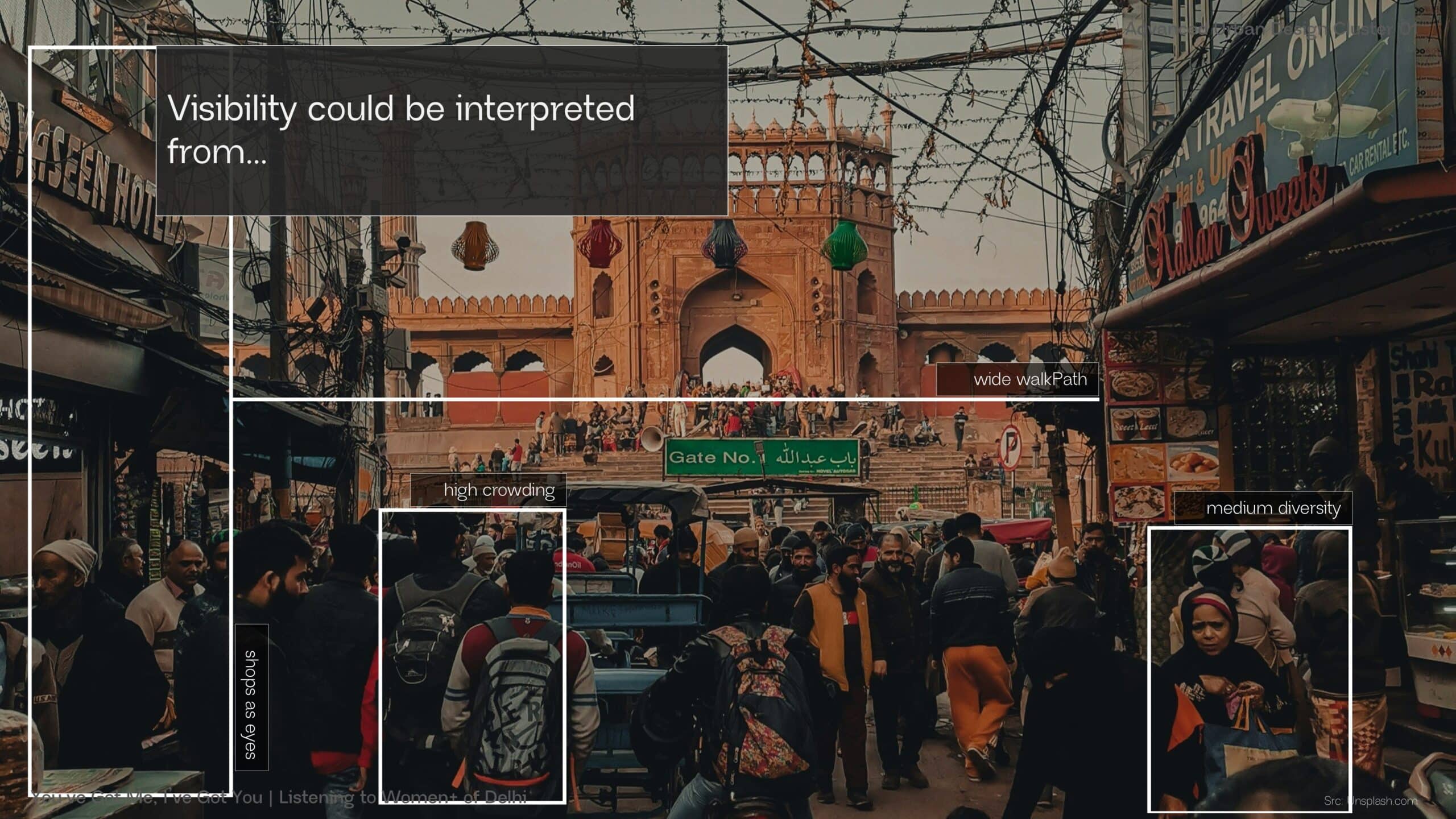

In the context of urban safety, visibility emerges as a layered and nuanced concept—one that cannot be reduced to mere illumination or visual access. It must be understood through its dual dimensions: projective visibility and introspective visibility.

In the context of urban safety, visibility emerges as a layered and nuanced concept—one that cannot be reduced to mere illumination or visual access. It must be understood through its dual dimensions: projective visibility and introspective visibility.

Projective visibility refers to the condition of being seen by others in a public space. It is inherently a collective experience, shaped by social surveillance, spatial openness, and the presence of “eyes on the street.” This kind of visibility can generate a sense of protection—when the eyes are perceived as caring, watchful, or community-oriented. However, projective visibility also carries a critical tension: the risk of being overexposed, surveilled, or objectified. In Delhi, women+ often describe the discomfort of being hyper-visible, especially in male-dominated or uncontrolled environments, where their presence invites not care, but scrutiny, harassment, or judgment. This complexity underscores that not all visibility is empowering; some forms of being seen can feel more like being on display than being safe.

On the other hand, introspective visibility describes an individual’s ability to see and make sense of their environment. It is a more personal and cognitive experience, rooted in spatial legibility and environmental awareness. When a woman+ can clearly identify exits, detect movement, spot other people (especially other women), and anticipate changes in her surroundings, she is more likely to feel in control and secure. Introspective visibility thus relates closely to autonomy and situational clarity—the ability to read space and respond accordingly.

These two dimensions often intersect in everyday navigation. For instance, a well-lit, crowded street may offer both strong projective and introspective visibility—making a woman+ feel both seen and aware. But their interplay can also create dissonance: a woman may be highly visible to others (projective) but unable to clearly see or assess her surroundings (introspective), resulting in heightened vulnerability.

Understanding this duality of visibility is essential to designing cities that are not only legible and well-lit, but also emotionally and socially responsive to the lived realities of women+. It is not enough to ensure that a woman is seen; how, by whom, and under what conditions she is seen makes all the difference between feeling watched and feeling safe.

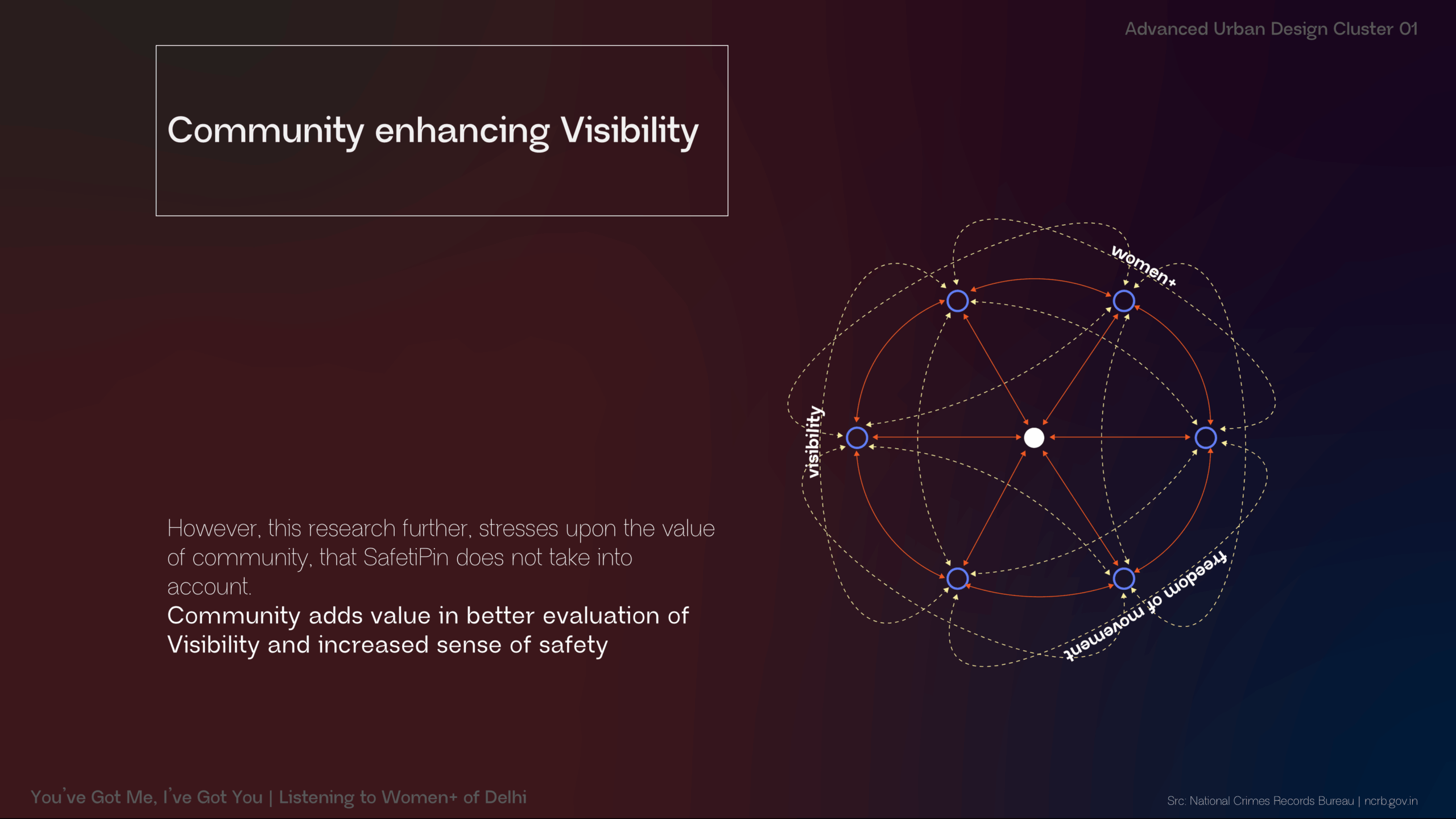

Building on the duality of visibility, this research emphasizes the crucial role of community in shaping and enhancing women+’s perception of safety. While tools such as SafetiPin have been instrumental in quantifying urban safety, they primarily rely on infrastructural and environmental parameters, leaving less room to account for the active agency of communities themselves in transforming how safety is experienced.

Community, in this context, is not merely a backdrop to urban life—it actively amplifies visibility. When women+ move through the city as part of a community, whether physically present or digitally connected, they benefit from an “extra set of eyes”: peers who watch out for them, affirm their presence, and extend a form of social protection that goes beyond formal surveillance. This collective visibility strengthens both projective visibility and introspective visibility. In this sense, community becomes a multiplier of visibility, filling the gaps left by infrastructure and policy. It reframes safety as not only the responsibility of the state or the outcome of design interventions but also as a collective practice of care. By centering women+ as both the subjects and agents of visibility, the research underscores how community-driven visibility directly empowers freedom of movement in Delhi and challenges the conditions that otherwise restrict it.

Chapter 03: Designing Women+ Safety Systems

explore collective systems that support peer-based, trust driven navigation for women+

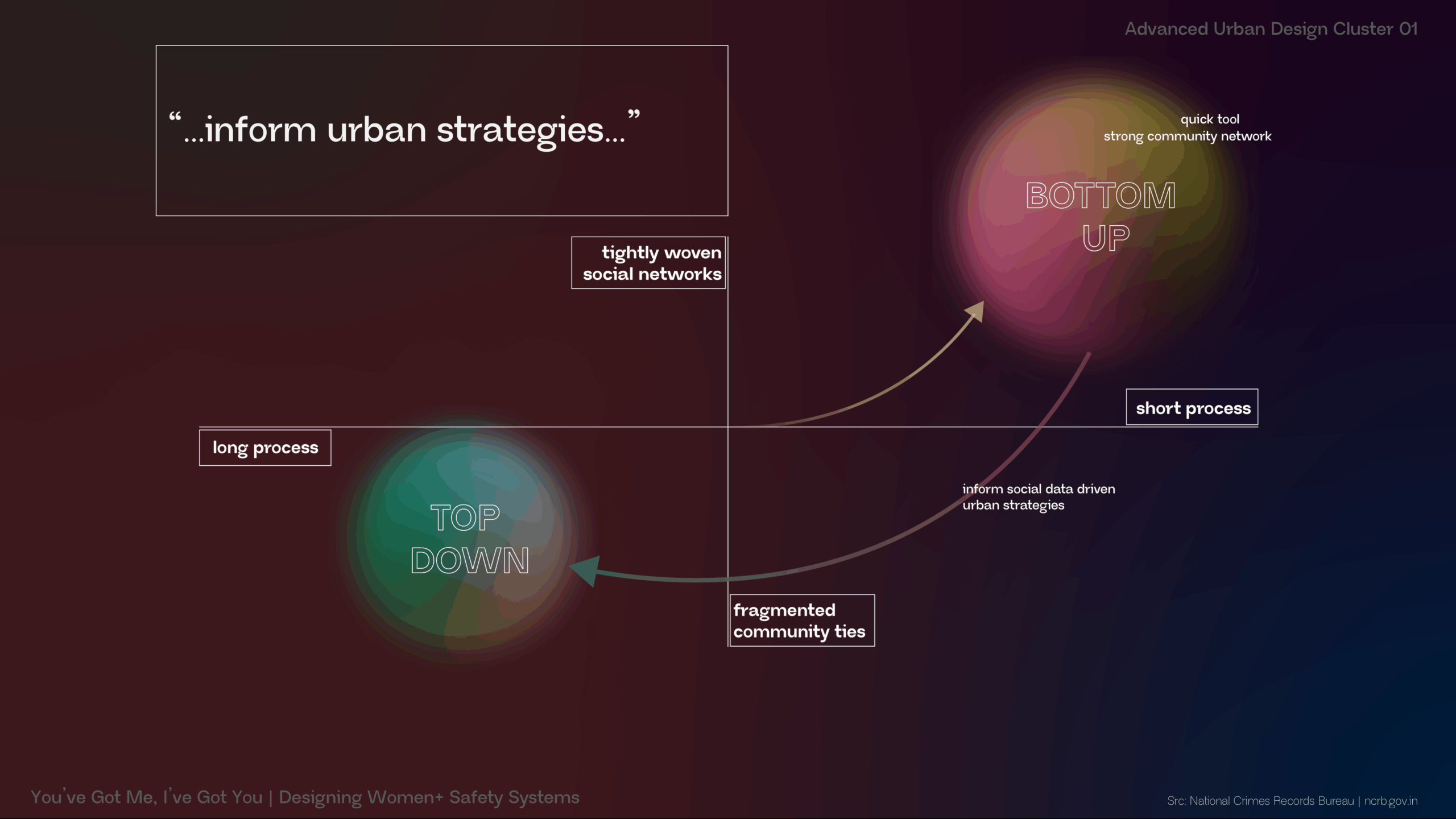

In order to move from insights to actionable strategies, this research turns to the design and evaluation of women+ safety systems. These are frameworks that allow women+ to navigate the city through collective, peer-based, and trust-driven mechanisms. These systems are not meant to replace infrastructural or institutional interventions but to complement them, bridging the gap between the immediacy of lived experiences and the longer timelines of top-down urban governance.

Broadly, such systems can be approached in two ways. A top-down approach, typically led by government institutions, policy bodies, or large-scale urban projects, often results in structural changes. While necessary, these interventions usually require extended timelines, heavy investment, and stakeholders beyond the immediate community. By contrast, a bottom-up approach emerges directly from within the social networks of the community in focus. It is more agile, more responsive, and more tightly woven into everyday practices of safety and care. This approach acknowledges the urgency of the issue: women+ cannot wait for decades of policy shifts to feel safe in their daily lives. Instead, by harnessing the knowledge, trust, and solidarity already present in their communities, bottom-up safety systems can provide immediate, flexible solutions that both support present needs and inform longer-term strategies.

For this research, the focus lies firmly on the bottom-up approach in the form of an app, i.e. on systems of collective care that allow women+ to act as each other’s safety nets in the city. Ultimately, this does not mean rejecting top-down interventions. Rather, it means that bottom-up systems can produce the social and perceptual data necessary to influence policy. When aggregated, the everyday safety practices of women+ offer a powerful evidence base to guide inclusive urban design and planning.

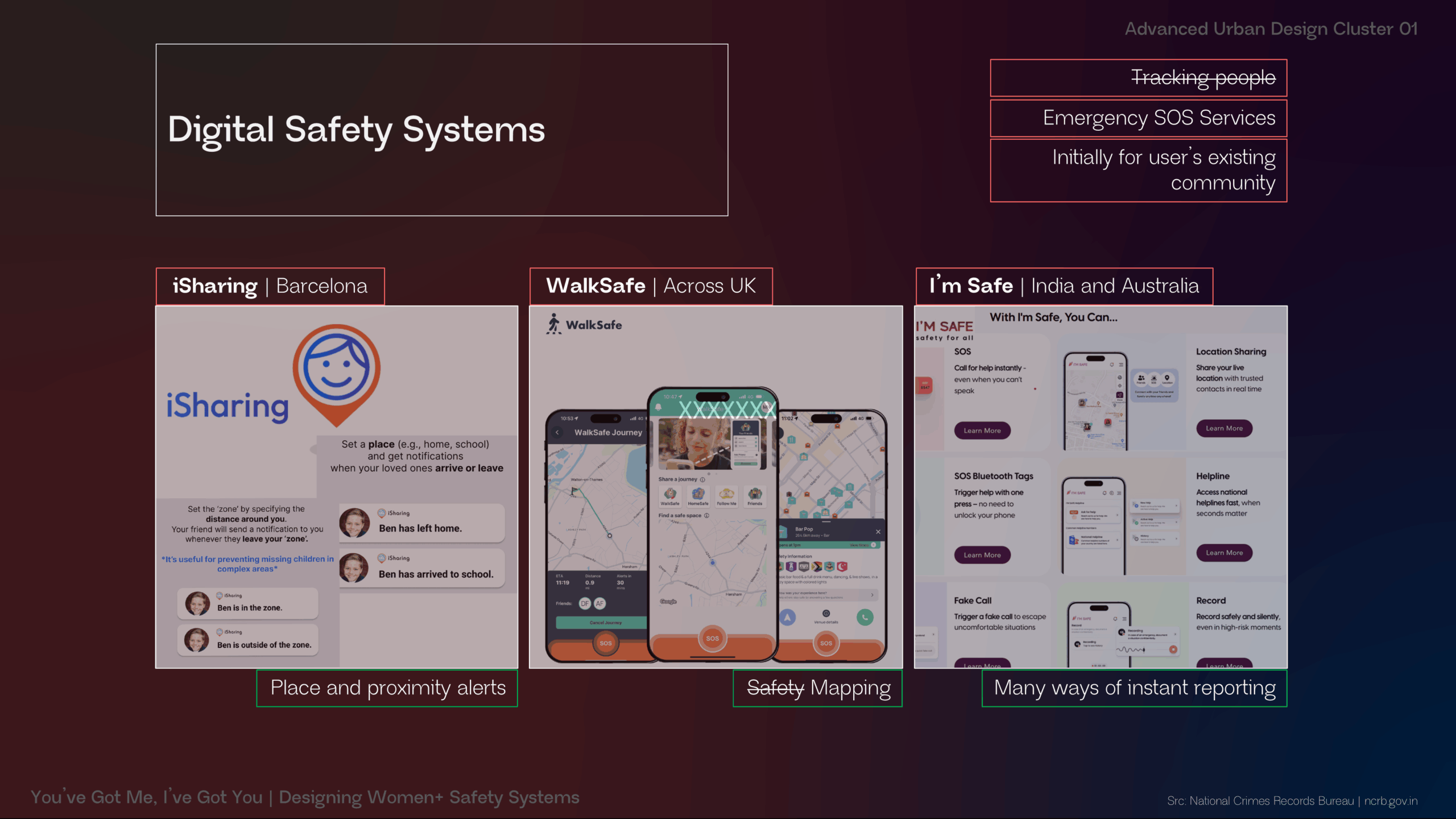

In order to ground this research in practice, it was essential to examine both global digital safety systems and community-based initiatives within India.

Worldwide, platforms such as iSharing, WalkSafe, and I’m Safe have introduced key features that seek to enhance personal security in urban contexts. These include place and proximity alerts, safety mapping, instant reporting mechanisms, and emergency SOS services. Collectively, these features demonstrate the capacity of technology to act as a protective layer, offering users immediate tools for risk mitigation and response. However, while these systems are valuable, they also raise critical questions about their long-term implications. Safety mapping, for instance, often tends to produce “maps of fear” which end up reinforcing the image of cities as hostile rather than reclaimable spaces for women+. For Delhi, a city already burdened with narratives of risk, the challenge lies in adapting these functions in ways that are discreet, intuitive, and empowering. The intent, therefore, is not only to keep users safe in the moment but also to generate a more nuanced dataset of safety perceptions, one that reflects trust, presence, and belonging.

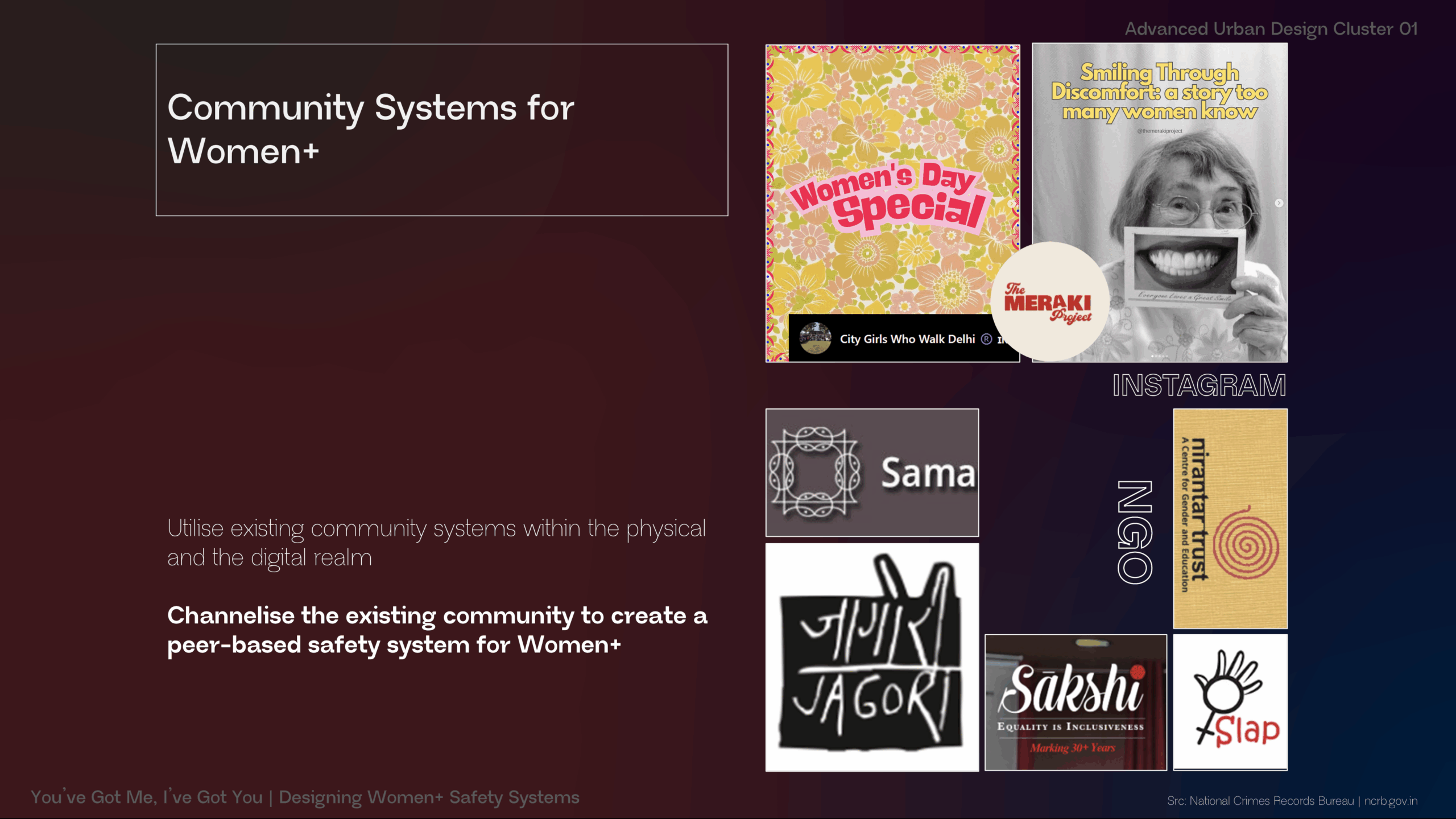

Turning to India, the study recognizes the importance of existing community systems that women+ already rely on, both in physical and digital realms. These include NGOs dedicated to women’s welfare, informal digital collectives such as Instagram groups and pages that share safety tips or solidarity networks, and transport initiatives run by women for women. These grassroots systems function as peer-based support structures, rooted in trust and solidarity rather than formal surveillance. They demonstrate how women+ already build safety through social connection, mutual aid, and shared visibility, even in the absence of institutional interventions.

Integrating lessons from both scales, i.e., the technological strengths of global digital systems and the embedded trust of local community networks, this research identifies a pathway toward safety systems that are both responsive and relational. By weaving together digital tools with the lived practices of women+ in Delhi, such systems can go beyond transactional safety to create a culture of collective care and presence in the city.

Chapter 04: ToGetHer Safe

a tool that offers agency to women for community building through collective wayfinding and safety optioneering

In urban environments, particularly in cities like Delhi, the act of moving through public spaces is often fraught with anxiety for women and gender minorities. Traditional navigation tools fall short of addressing the complex emotional, social, and safety concerns that come with mobility in these contexts. ToGetHer Safe emerges in response to this gap, not just as a navigation app, but as a community-powered safety network designed by and for women. At its core, ToGetHer Safe combines the practicality of wayfinding with the strength of social networking, creating a digital space where safety is not just an individual concern but a shared practice. The app equips users with a range of collective navigation tools that transform everyday movement into a peer-supported experience. Whether walking, commuting, or pooling rides, users can select from safety-enhancing features such as Pink Cabs, Visibility Navigation, Pooling, and Walking Mode. These options reflect the concept of “safety optioneering”, an approach that prioritizes choice, contextual decision-making, and community participation over reactive measures.

The app achieves its objectives through three interconnected pillars: Safe Navigation, Safe Bystanding, and Safe Community. Together, these reinforce the idea that safety in Delhi’s urban spaces is both dynamic and static, sustained by the collective presence of women who make visibility a shared experience at all times.

To better understand the workings of ToGetHer Safe, the app can be explored through interconnected scenarios that reflect moments in a woman’s daily life. These scenarios situate the app in context, showing how its functions support users when they feel vulnerable rather than demanding constant use. The app is not designed as a tool of continuous engagement but as a trusted companion, only activated in specific moments of uncertainty, discomfort, or risk. Together, its features provide both practical safety tools and a sense of community care, ensuring that women know the city can be navigated with others watching out for them.

Conclusion

Conclusively, this research aims to present a comprehensive understanding of how women’s safety, or the lack thereof, affects their agency and freedom of movement in Delhi’s public spaces, to which they are entitled as equal citizens. Beyond infrastructure and policy, a core finding is the crucial role of community in shaping women’s perception of safety. Collective observation, peer support, and shared vigilance not only enhance projective and introspective visibility but also restore agency by allowing women to navigate urban spaces confidently, knowing they are not alone. Identifying gaps in official data, scholarly work, and existing safety systems highlights how current approaches fail to empower women or integrate their voices meaningfully into decision-making. While quantitative and qualitative data are essential, gender-disaggregated insights combined with lived experiences and contextual knowledge provide a richer understanding of urban safety.

This study proposes ToGetHer Safe, an app that combines visibility-based navigation, community-driven support, and real-time safety interventions, amplifying women’s voices and concerns in daily decision-making, whether in urban planning, policy, or infrastructural design. The app embodies a bottom-up, feminist approach, leveraging both introspective and projective visibility and creating a network of trust and mutual care. Importantly, the app also functions as a research tool, generating human-centric data to inform future interventions while protecting privacy. Ultimately, the goal is to work toward gender-just cities, where safety is not contingent on temporary tools but embedded in the urban environment itself. The app represents an experimental step in this direction, bridging gaps between lived experience, community agency, and formal interventions. Long-term, true urban safety for women will render such tools redundant, achieved through inclusive, responsive, and relational systems across both bottom-up and top-down strategies