Convened in Rome, 08 June 2022

A CALL TO ACTION

The following blog post contains the 12 principles that the Charter looks at highlighting and emphasizing through the document. The students of the Masters in Advanced Ecological Buildings and Biocities has proceeded to create diagrams for each of the principles to aid in the process of understanding these parameters.

1. INVEST IN NATURE

“Nature is the existential infrastructure of life on earth—including human life—and the only solution to heal the planetary crisis. We must seek out, learn from, and invest in the pro found intelligence and enduring lessons that a healthy biosphere can offer us. There can be no investment in cities — whether intellectual, spiritual, political, social, or economic — without a corresponding, coordinated, and continually renewed investment in the natural systems that surround and suffuse them. Without an inextricable and enduring alliance between urbanity and nature, the concepts of energy efficiency, carbon neutrality, human health, economic vitality, and environmental sustainability are meaningless. Eco-systemic well-being, which includes humanity but is not limited to our species, must be understood as a basic right of all citizens and the organisms that contribute to the health of our terrestrial metabolism. Integrating natural systems such as forest, grass- and wetlands, and marine biomes into cityscapes is essential for human health and wellbeing. These are the systems that draw down excess carbon dioxide, absorb and cleanse the storm-water runoff of our streets, shade our homes and our urban meanderings from the heat of harsh sun light, infuse our dwellings with re-oxygenated air, protect buildings from the ravages of wildfire and flooding, and remind us of our embodied relationship with our fellow species. Far beyond the tattered perimeters of our urbanized landscapes, the systemic benefits of nature accrue rapidly across vast timescales and geographies.”

add text explaining the diagram here…..

2. EXPAND THE SYSTEM BOUNDARIES OF DESIGN AND GOVERNANCE AND THE TEMPORAL AND SPATIAL SCALES OF OUR AGENCY

“Neither buildings nor cities are closed systems. They are, instead, in a continuous negotiation of energy and material with their immediate sites and broader hinterlands. We must marshal human experimentation and innovation—and the collaborative economic enterprises that may arise from them—to drastically limit negative impacts and embrace sys temic, trans-scalar, and cross-sector environmental benefit. With each constructed element we conceive—from a structural component to an urban district—we must design not just its form but its full life cycle. With each material, assemblage, or city block we imagine and implement, we must discipline our demands to reflect the capacity of our regions to sup ply it, to acknowledge and adapt to scarcity, and to respect — and even celebrate — those constraints. Bio-regionality, the remapping of jurisdictional boundaries to reflect a region’s natural ecological function, must replace the artificial divisions rooted in political affiliation that have prevented the effective governance of our environmental resource and the ecosystems that are our natural infrastructure.”

The second point of the charter highlights the concept of bio-regionalism. Bioregionalism sees humanity as a part of nature and focuses on building symbiotic relationships between sociological and environmental environments. The cities are designed to discard political boundaries for ones that respect and celebrate the natural laws of ecological and geographic boundaries. The remapping of jurisdictional boundaries integrates water and forest resources to protect ecosystem functions. The city is no more considered a closed system but is connected through hubs and corridors to accommodate farmlands, urban forests, parks and wetlands. The system integrates agriculture, industry, economics and governance together with the ecology of the region. Non-human nature and biodiversity are invited to thrive within the city instead of existing in isolated pockets.

The city utilizes local materials and sources energy from the elements present in the region. These resources and constraints make room for innovation and region-specific solutions. The city works toward producing local foods and employing natural infrastructure. This way the system gains self-reliance which further restores local ecosystems and renews traditions. Several such cities would form organic groups that attend to demands, and exchange surpluses to build resilience against climate change.

3. ENHANCE RATHER THAN DEPLETE BIODIVERSITY

“We must thread sensitive and synergistic loops of feedback through our source ecosystems and the urban supply chains that pull on them. When we strip land of life-giving soils, flora, and fauna, or extract ore and minerals from the geological sub-strata to form our cities, we disable the essential and productive biological capacity of the earth. Every existing disturbance to ecological systems—except the blind extraction of material and energy for short term gain—represents an opportunity. By valuing biodiversity and embracing the range, complexity, and constructive potential of our natural landscapes, we can supply renewable materials and services for our cities, while improving the health, diversity, and expansion of those same natural systems. Rather than demand that forests produce certain prized-grades or uniform species with which to build, we must instead ask what forests can naturally provide while maintaining their inherent biodiversity. In place of destructive over-farming or the filling of wetlands for suburban expansion, building and agriculture can serve to restore soil and regenerate habitat, while enlightening our interaction with the landscapes we once abused. In addition to eco-systemic restoration, this optimized relationship with nature allows critical habitats and ecosystems to remain wholly undisturbed and trans forms our cities from predatory consumers into regenerative forces for nature.”

(by Basant Abdelrahman and Raffaele Schiavello)

“The Global Wetland Outlook is a wake-up call – not only on the steep rate of loss of the world’s wetlands but also on the critical services they provide. Without them, the global agenda on sustainable development will not be achieved,” says Martha Rojas Urrego, Secretary General of the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands.

The importance of wetlands is often overlooked even though they play a vital role in the mitigation of climate change and the gain of biodiversity. In “Toward re-entanglement: a charter for the city and the earth”, it is stated that the filling of wetlands for expanding urban areas has become a common practice that has devastating consequences to biodiversity. By reconstructing wetlands in an urban context and integrating it within the fabric of the city, we can revive and restore the quality of soil and regenerate the habitat that was once lost due to urbanization. Biodiversity’s benefits extend way beyond animal welfare, in fact it is as immensely important to nature as it is to human society. The ecosystem services a wetland can provide for an urban setting can cover topics such as material welfare, security of communities and human wellbeing. The concept of the diagram is to design a city that conforms with the demand of nature rather than the reverse. A city that has no value for its natural landscapes will lose far more than biodiversity, it will alter the quality of life itself. The diagram represents data gathered through articles about the impact a wetland has on its surroundings. This is divided into three separate phases; an untouched wetland, urbanization, and lastly an urban wetland. An untouched wetland is the most optimum form of natural landscape, as it encapsulates the literal definition of biodiversity. Statistically, these areas are also rich in minerals and resources, usually becoming the target for extraction of material and energy for short term gain. Alternatively these areas are often targeted for urbanization tactics as well. Phase two of the diagram represents the negative impact of urbanization on an area that is planned without any consideration of the repercussions it may have on the site. If nature is not the first priority while planning the construction of the city, we may lose much more than we think. In fact, we can lead to the extinction of certain species that depend on these wetlands for survival. Phase three depicts the importance of wetlands and how essential it is to plan a city around it. Wetlands do not simply serve nature but can assist in creating a much more sustainable and efficient city. It ranges from reducing heat island effect to preventing flooding and cleaning our drinking water. Raising awareness about the importance of wetlands is crucial in our fight against climate change, because the eradication of nature has a devastating impact on every aspect of our lives including our health, population and wildlife.

4. SINK CARBON BY CONSTRUCTION

“We can transform cities from climate culprits into carbon banks, offsetting the significant lifecycle impacts created by their greenhouse gas emissions. If constructed and maintained with regeneratively sourced and renewable, bio-based materials—timber, bamboo, plants, and agricultural waste products—buildings, infrastructures, and entire urban systems can reliably store significant amounts of bio-genic carbon. Where plant cellulose can replace the energy- and emissions-intensive classes of mineral-based and petrochemically-synthesized materials such as concrete, steel, and plastics; when we can deploy biomaterials at the scale of cities, over repeated cycles of recovery and reuse; and where those plant fibers flow naturally from the yields of ecological silviculture or community-based regenerative agricultural activity, they can form massive and durable urban carbon sinks. By forging biological value chains that incentivize the protection, restoration, and expansion of global forests, we also create opportunities for meaningful and dignified rural employment. Meanwhile, those sustainably managed source forests will continue to absorb more atmospheric CO2 in future cycles of natural (and, where necessary, enhanced) regeneration. Where bio-genic materials and processes cannot be applied to a cities, buildings, and infrastructure, we must strive to continually decarbonize and optimize manufacturing processes, while seeking to minimize—and ultimately re-use—the number of carbon-emitting materials we use.”

[Source: Disha Arora and Ruhani Adlakha]

? Forests(timber/bamboo) sequester carbon: Trees sequester carbon during their life, pull carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and store it in its mass, roots, and surrounding soil until the tree burns or decomposes, or the soil is disturbed, at which point CO2 is re-released into the atmosphere. Forests have the potential to remove and store a significant amount of the excess CO2 now in the atmosphere, and therefore play a significant role in our planet’s ability to regulate warming and carbon emissions.

? Cities as carbon sinks and optimized manufacturing processes: Carbon is typically re-released at the end of material life cycles due to combustion and/or decomposition; there are climate benefits of sequestering atmospheric carbon within long-lived timber products that act as a carbon sink. For example, delaying carbon emissions reduce cumulative climatic energy input, buys time for adaptation of both natural and man-made systems reduces the possibility of reaching dangerous climate ‘tipping points and increases the potential for permanent storage through future technologies such as ‘carbon capture and storage’. The use of Biogenic materials makes cities Carbon Sinks. However, in places where they cannot be used, construction materials can be sourced from demolished buildings through the process of ‘Urban Mining’.

? Repeated Reuse of Materials prevents Carbon Decay: Typically, carbon re-emission at a building’s end-of-life nullifies the sequestered carbon. Carbon capture or preservation measures, such as continual reuse of the building’s materials could lead to zero or negative emissions. In order to avoid carbon decay in the future and to improve manufacturing processes, continuous re-use may entail recycling materials and/or reusing them in cities.

5. CAPTURE NATURAL ENERGY RATHER THAN EXTRACTING FOSSIL FUELS

“Our buildings and cities, and the sub- and ex-urban landscapes that emanate from them, are net energy consumers. In our technological zeal to invent elaborate mechanical systems to manage the quality and temperature of our air, we have failed to observe the abundant benefits of nature and the eco-systemic services it can offer us. Rather than learn from natural physical, chemical, and biological phenomena, we continually attempt to refine dys functional and rapidly obsolescent technical facsimiles. We have yet to take full advantage of the potential active and passive thermodynamic exchanges and energy generation associated with the vast surfaces we have arrayed across our constructed landscapes. The particular properties of the material that comprise them — their density, reflectivity, chemical composition, even color – may serve as media for energy exchange, rather than the source of overheated urban corridors and spaces. Building walls and roofs must be reconfigured to optimize solar orientation and radiation and facilitate its transformation into useable energy. Foundations and structural walls can serve as thermal mass to sink excess heat or cold and serve as media for heat exchange. Coupled with the reduction of production stage energy consumption, these lifecycle strategies may offset the loads of sectors unable to meet their own energy demands. Through the creative reimagination and reconfiguration of material applications, and the careful layering of building and infrastructural assemblies, we may supplant our reflexive focus on engineering mechanical heating and cooling equip ment and redirect squandered heat energy as a means to temper urban dwelling. Through the careful planting of trees to provide shade, the reintroduction of urban greenways and -spaces to absorb UV energy and reduce surface albedo, by threading re-naturalized waterbodies through our urban fabric to enhance evaporative cooling, we can reduce the heat gain in our public spaces and cooling requirements of our homes.”

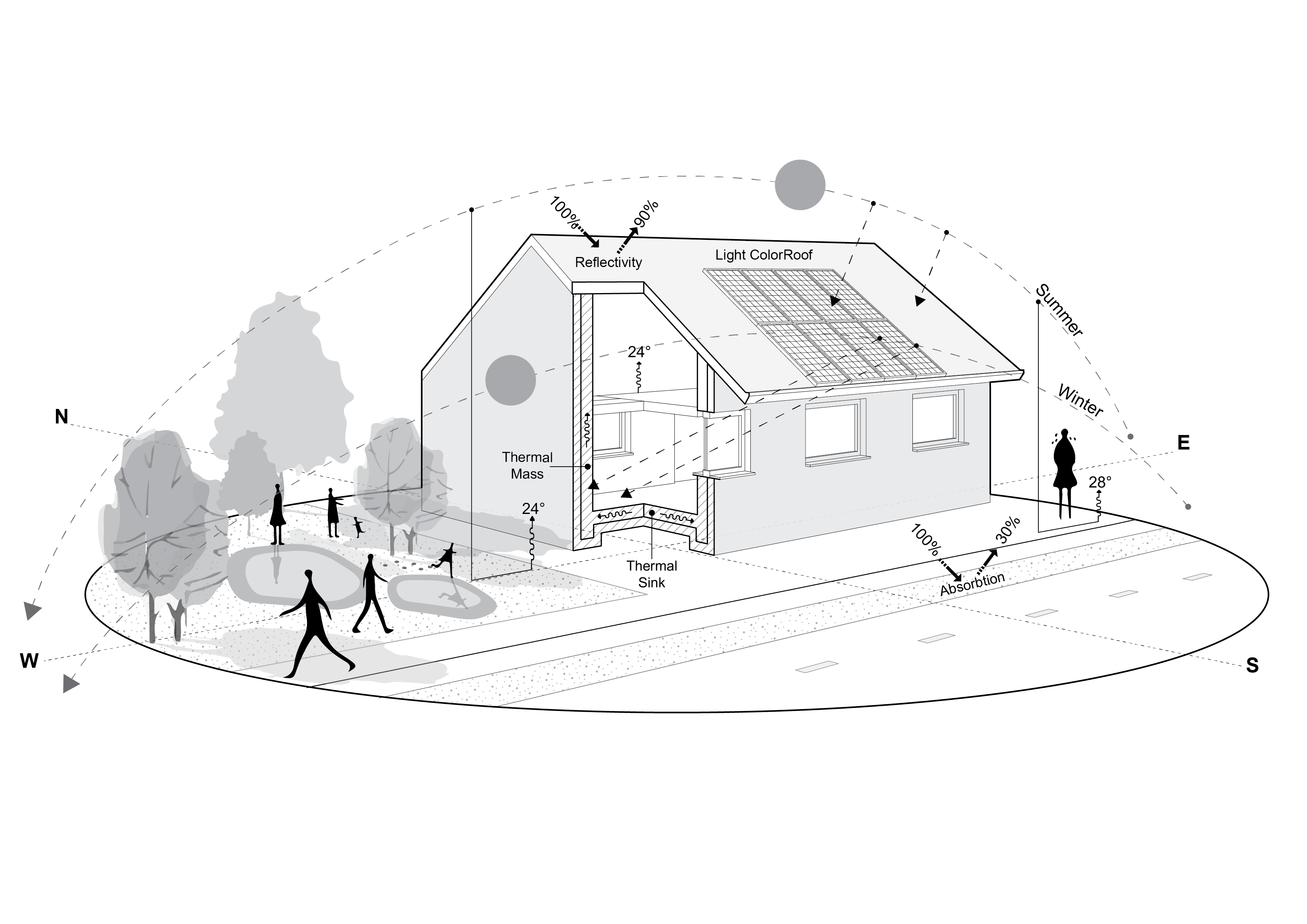

Energy circulation methods based on mechanical systems feeding on fossil fuels fail to supply the needs of modern cities. The future of sustainable city management lies in the careful planning of city zoning, and the immediate reintroduction of curated green spaces. Residential buildings have an almost untapped potential to function as independent energy systems and carbon sinks. Solar energy should be stored within the building’s structure, and coupled with controlled natural heat exchange to minimalize the need for mechanical ventilation. The cooling capabilities of urban forestry and water reservoirs should be used directly for the benefit of the urban environment.

With the diagram what we seek to explain is what would be the ideal situation of a house to take advantage of the natural factors, so that they can be used optimally. Some of these factors are:

- Orientation of the sun: Placing the house with the correct orientation of the facades, to take advantage of the desired benefits, should be located so that the shorter facades, with smaller windows, are positioned to the east and west, and the longest facades with larger windows to the north and south. Considering that the sun changes according to the seasons of the year, we must take advantage of the direction of the sun that is generated in winter, so that it helps to heat the interior of the house and on the other hand we try to prevent the summer sun from entering, in order to avoid high temperatures in the interior.

- Perpendicular roof: The pitch and orientation of the roof plays an important role in the placement of PV panels. The diagram presents a setup optimal for the northern hemisphere. The panels are placed on the south facing facade on a roof with a pitch correlated to the specific geographic latitude.

- Colour: Colour, chemical structure and surface composition of the construction material influences its reflectivity. Lighter materials reflect bigger spectrum of wavelengths, while darker materials absorb them, which results in the increase in temperature. The house in our diagram has a light coloured roof for additional cooling effect.

- Wall and foundation thickness: The additional thickness of walls and its material composition results in improved thermal capabilities of the building’s interior. They can become a thermal sink for heat – during the day they accumulate heat gained from sunlight and during the night they radiate it back to the atmosphere.

- Vegetation: The importance of planting trees to create cooler environments thanks to their shades.

- Water bodies: They help to cool the environment and lower temperatures in the open air.

- Greenways: Absorbs the UV generated by the sun.

6. QUESTION WHY WE BUILD AND WHAT WE BUILD WITH WHILE PRIORITIZING THE REUSE OF EXISTING BUILDINGS AND MATERIAL

“Rather than assuming the solution to any urban building need is the extraction, processing, and consumption of virgin raw material to construct new buildings and infrastructure, we must stringently re-evaluate (and creatively re-value) what we have already made. By siphoning off-waste streams from industrial and consumer activity in the repair and retrofit of existing structures, we can create new, value-added processes that transform discarded and devalued matter into new forms of “raw” industrial material while revitalizing our urban habitats. When we promote circularity through multiple cycles of material reuse and embrace the repair, maintenance, and upgrade of our current building stock, we avoid a whole new set of environmental burdens, ecological disturbances, and the social dislocations they entail. Our critical assessment of the very premise of new building must accompany a rigorous analysis of the materials and spaces we truly need. These fundamental reflections and subsequent analyses must precede any refinements in technology and efficiency that have become the reflexive response of the global building sector’s current approach to “sustainability.””

Recently, humankind has entered what is called the “Anthropocene Era.” This time-period is marked by the fact that human-made material has now surpassed total biomass material on the planet. This is a milestone for human history. It is the post-industrial era. Before we continue building with no limit, we must stop, reassess, and look where we came from. And furthermore, we must take critical action in construction and design practices to build with a healthier planet, rather than against one.

As development continues, it is vital for stakeholders to analyze and revise the material input streams for construction. This process revolves around the warehousing industry to properly receive, catalog, and distribute specific materials to be used in shaping the built environment. As more sustainable inputs enter the material flow, the need for raw materials can decline. This will yield higher environmental value in the process. As mentioned with the Anthropocene Era, the existing building and infrastructure stock on Earth is significant. Rather than demolishing outdated buildings and discarding them to a landfill, many of the components can and must be repurposed and reused. This may lead to the creation of economic value and new markets for construction materials. Furthermore, we must evaluate other consumer waste streams to again give matters from various disciplines longer life spans before being deemed waste.

It is not only important to reconfigure the inputs to the design and construction industry, but also the outputs. To again lessen the environmental repercussions of human development, we must take care of what we have already constructed. Prioritizing the repair and maintenance of the existing building stock is too often overlooked with the fast-paced modern world. When communities grow, adaptive reuse can be a sustainable alternative to demolition by repurposing key elements of the existing structure. And finally, when new buildings are designed for construction, they must also be designed for disassembly. This will create more opportunities for necessary circularity in the material flow. With thoughtful, diligent measures, we can redirect our trajectory to one with reduced reliance on natural resources. In the end, this will reveal beneficial effects on the environment and therefore on ourselves.

7. BUILD DENSE AND POLYCENTRIC CITIES TO RESTORE URBAN COMMUNITIES AND REGIONAL WILDLANDS

“Cities, when convivially organized and clearly bounded, are inherently efficient organisms. By reigning in their spatial extents, we avoid the conversion of biologically productive land into sprawling, infrastructurally attenuated, automobile-oriented hardscapes. Instead, we can optimize land already assigned to the urban sphere and thereby instill in it more profound value. Dense, mixed-use neighborhoods where citizens can live, work, and play enhance urban quality and reduce infrastructural requirements across all scales of urban inhabitation: exterior building envelopes and systems, when shared by multiple urban households, in multi-story buildings, reduce per capita embodied emissions; easy and equitable access to livelihoods, social facilities and services reduce the externalized costs and emissions of long commutes. Efficient networks of mass transport and mobility de-emphasize the use of automobiles and trucks within the city, reducing the energy consumed, the pollution emitted, and the vast area of land required. That land, in turn, can be reassigned as public pedestrian corridors, and green spaces, and promote the careful restoration of natural forests, wetlands, and other ecologically critical landscapes. Dense and efficient polycentric cities can replace unconstrained urban sprawl, eliminate often neglected and undervalued urban peripheries, and clarify and enrich the interaction between those convivial cities and the healthy wildlands that border them.”

[Source : Indraneel Joshi and Shruti Sahasrabudhe]

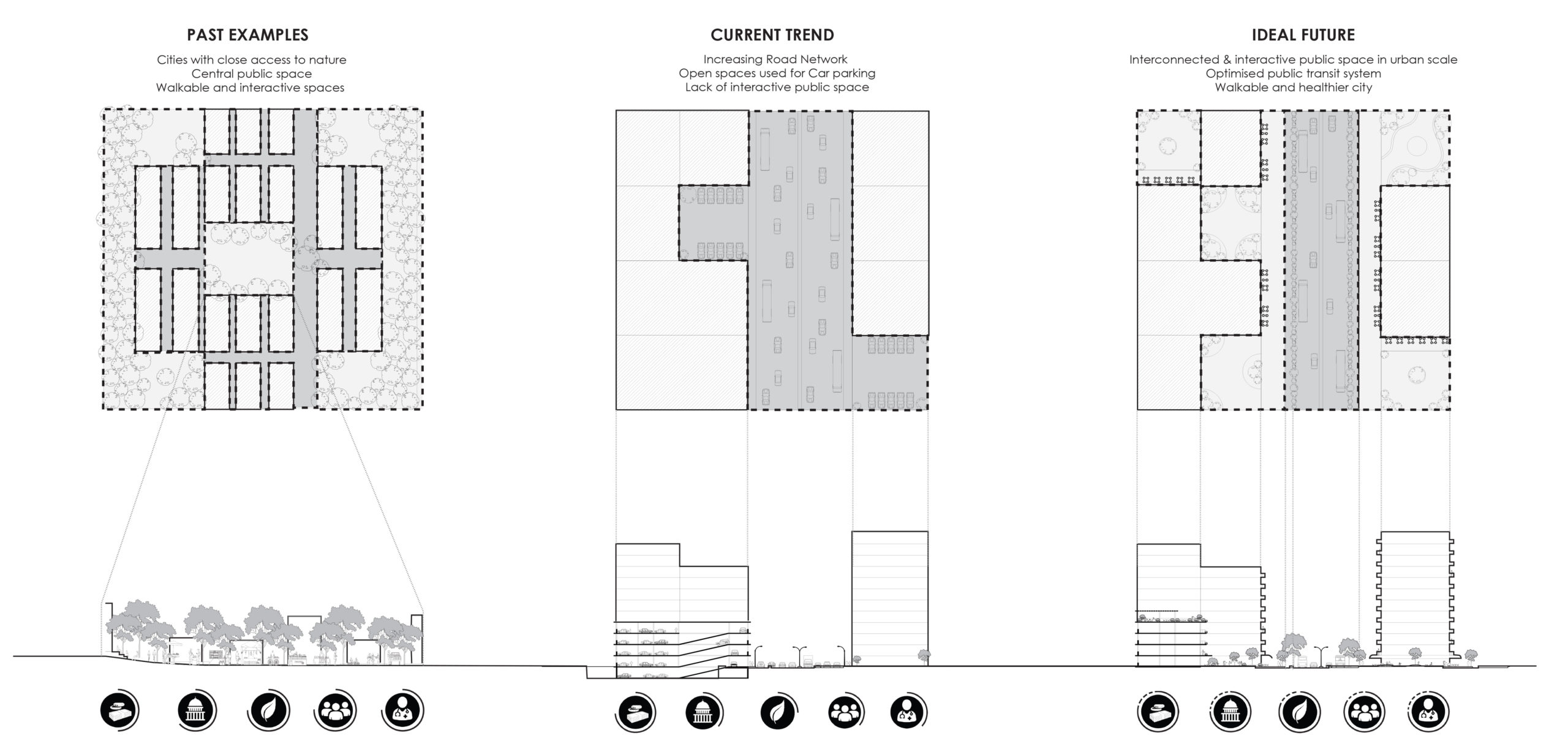

The key to efficient and convivial cities is to reign in their spatial extents and focus on mixed-use neighborhoods. This allows citizens to live, work, and play in the same area, reducing the need for long commutes and the associated externalized costs. Additionally, this type of urban layout reduces the need for automobiles and trucks within the city, reducing energy consumption and pollution. By promoting public pedestrian corridors, and green spaces, and restoring natural landscapes, cities can become more efficient and convivial while also preserving the environment. Consequently, this chain leads to reduced per capita embodied emissions.

8. PROVIDE SECURE AND DIGNIFIED HOMES FOR ALL PEOPLE TO BUILD SOCIAL EQUITY, ECONOMIC LIVELIHOOD, AND SHARED RESPECT FOR OUR COMMON RESOURCES

“Housing is not merely a means of survival, a commercial product, or an investment instrument. Housing, understood as dwelling, provides homes where individuals and families can grow and evolve comfortably, within well-considered, functional, healthy, and spiritually restorative spaces. Those under-served and disenfranchised populations, who struggle for access to the bare minimum of resources and services, have become the first victims of our environmental crisis. The basic human right to dwell safely, securely, and with dignity, must become our universal objective. The making of secure and dignified homes for all is the means to meet a dire need, reduce vulnerability, build equity, and empower and stabilize individuals and households, their communities and, by extension, the resource landscapes that supply them. Stable homes, and the regenerative and equitable design and construction practices that produce them, create employment opportunities all along the building value chain and promote durable investment in people across all sectors of society. Our failure to make it so will only exacerbate social inequities and drive ever-deepening exploitation of our dwindling natural world.”

Housing is a human need that many people currently do not have access to. The present day housing crisis is characterized by vast wealth gaps pushing impoverished populations deeper into poverty and desperate situations. Oftentimes in an urban context, these under-served populations are subjugated to extremely dense, ill-equipped living conditions that only make it more difficult to improve quality of life and to gain a sense of stability. Access to clean water, sanitation, adequate living space, electricity, and internet to name a few, are all major obstacles these populations face. Additionally, insecure residential status in terms of legal ownership is another challenge that is present. Because of all of these factors, these populations experience the worst effects of extreme weather and disasters. In these conditions, with all of the obstacles that must be overcome, it is a cycle of poverty that is extremely difficult to get out of and one that encourages further and more extreme poverty.

A better way forward could be to spread resources more evenly, in turn diminishing the wealth gap, provide more robust programs to aid those struggling with finding housing, and to reorient and re-prioritize societal views regarding need in comparison to that of excess. Housing for all is a future that is attainable given the right allocation of resources. This scenario would incorporate less dense urban planning with adequate space given to vegetation, recreation, and community gathering spaces. Increasing the population that has access to well-equipped housing will yield positive effects that will ripple throughout society, from the way we interact with each other to the way we interact with the surrounding ecology.

9. MAKE PUBLIC SPACE THE ESSENTIAL INFRASTRUCTURE OF CITIES AND THE SITE OF SOCIO-POLITICAL DISCOURSE AND INNOVATION

“Our species can only mobilize our innovative capacities, determination, and solidarity to address our existential crisis if we build strong and cohesive societies. Rather than retreating into segregated islands of difference, we should focus on strengthening and expanding the tissues of public space. Public spaces have always been the locus of local democracy and participation; places where differences are negotiated and social bonds forged, and where a sense of community and belonging can emerge despite increasingly diverse and mobile global societies. The vast network of corridors and storage spaces built for cars and industrial use that dissect our cities must be reassigned and transformed into spaces that serve people and their needs. This is a critical lever with which we can convene societies across all generations, genders, social backgrounds, and abilities. While we acknowledge the networking power of digitalization, we believe it is the safe, walkable city and the physical, social encounters that occur there as the most effective means to promote our basic human right to participate, experiment, and reinvent – the right to live in the city.”

Public areas shape community ties in neighborhoods. They are places of encounter and can facilitate political mobilization, stimulate connections that help prevent crime. They are environments for interaction and exchange of ideas that impact the quality of the urban environment.

Traditionally, public spaces were used for cultural and economic activities; political discourses and recreation. These spaces fostered a sense of identity, communal bond among diverse groups of people and safety through social encounters. It gave the society a platform to put forth their ideas and innovations. Post industrialization and urbanization resulted in a depletion of public spaces which led to a more fragmented society and decline in physical and mental health of people.

Looking back at the benefits of the traditional public spaces and analyzing the depleting quality in new cities, it is undeniable that a radical change in the design of these spaces are necessary; to promote social, political,economical, environmental and health benefits associated with them.This can be achieved by active participation, experimentation and reinvention of the public spaces as an essential infrastructure of the cities.

Participate:

A .Bringing diverse groups of people,ethnicity, age group, gender,economic status together to foster a sense of community.

B . Cultural, Economic and political activities can be promoted to increase volunteerism.

C . Using the concept of “Eyes of the street”, public spaces can be used to make the city a safe place.

D . Seasonal festivals can be celebrated to bring the community together.

Experiment

A . Scale of the public spaces and its distribution in different parts of the city to experiment with connectivity and cultures.

B . Associating unique activities to certain parts of the city in its public spaces can help in giving identity to the various areas in the city.

C . Public spaces can be specially designed to improve physical and mental health of the community.

D . Local businesses can be given a chance to prosper in the public spaces leading to growth in local economies.

Reinvent

A . The abandoned spaces in the cities like parking lots and industrial areas could be refurbished. It would reactivate the abandoned areas and make them a safer space for the community.

B . Old public spaces can be brought back to life promoting tourism. We could bring back the old customs and rituals with these old public spaces connecting people back to their roots.

C . Green interventions in existing hardscapes can help in bringing biodiversity into the urban landscape.

Public spaces can be an essential tool to build strong and cohesive societies through active participation of government, general citizens, public and private sectors. Improving technologies has brought people together virtually. While we appreciate the networking power of digitalization, we believe that public spaces create protected, walkable cities and the physical, social encounters that occur, are the most effective means of promoting our basic human right to engage, innovate, and reimagine – the privilege to live in the city.

10. EMPOWER RURAL COMMUNITIES AND ENGAGE THE TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICE OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND NON-WESTERN CULTURES

“The inextricable relationship between dense, vibrant cities and the ecosystems and human settlements of their hinterlands depends on the sustaining and rewarding employment of the individuals and communities who choose to dwell there. The re-valuation of rural lives and spaces — whether tended as agricultural land or maintained as ecological preserve —is essential to overcome cultural and political antagonisms and arrest the relentless consumption and devaluation of natural systems. The deep cultural knowledge and traditional practices of rural inhabitants offer lessons and value for the regenerative management of regional ecological resources. By building on local tradition we resist the universalising force of modernity and embrace place-based knowledge. We must reapportion economic power at local, regional, and global scales by focusing on the rural communities and their sustenance, reinstate and enforce the development rights of indigenous communities where they have been suppressed to promote access to opportunity, shift established administrative and regulatory jurisdictions where they fail to meet need or effectively govern, and redistribute the responsibility for the procurement of resources and the production and management of our human habitat.”

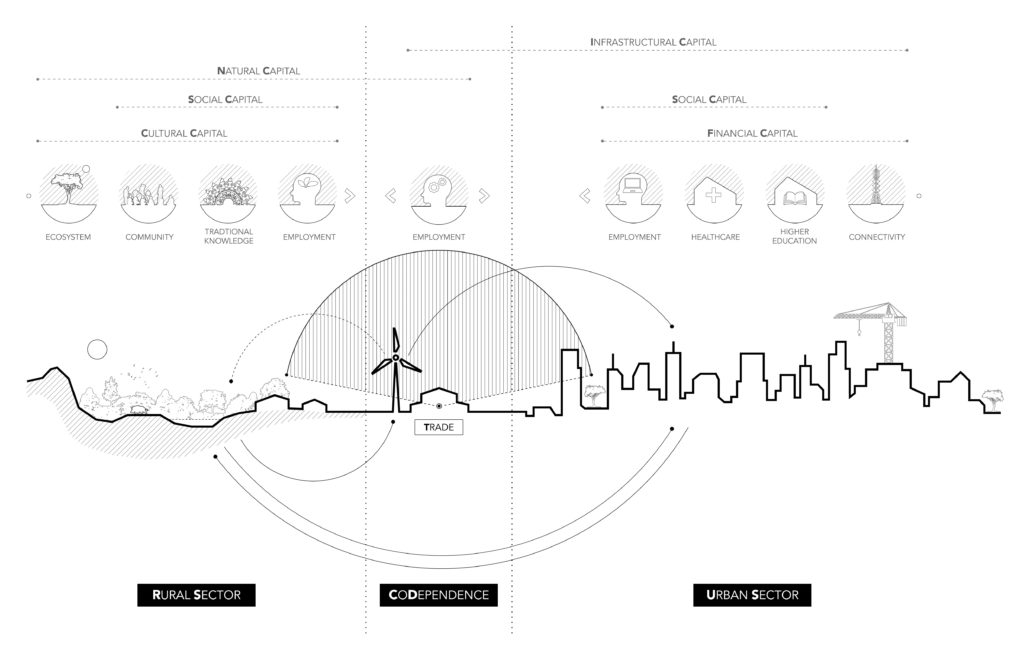

To empower rural communities, one must first understand the intrinsic values that govern the functionality of a settlement and the community as a whole. Regardless of their geographic location, rural communities rely on five primary factors to govern their lifestyle. Land, Water, Flora, Fauna & Man together create the crux of any rural community. These five elements share a circular codependent relationship where one cannot survive without the other, the absence of one causes an imbalance in the ecosystem.

The world as we see it today is exposed to certain advancements that can be looked upon as catalysts for the empowerment of these rural settlements. What we need today more than ever is a resilient community, one that does not depend on external forces for its survival but rather is able to withstand the issues we face globally. The nine factors of a resilient community can be identified as Shelter, Food & Water Security, Clothing, Education, Disaster Management, Healthcare, Energy, Connectivity and Trade. To create a resilient community, it must meet all 9 criteria. Contrary to popular belief, to empower the rural community the flow of resources is not unidirectional from the urban to the rural, but rather an undefined circularity that connects the rural fabric to the urban fabric. The exchange of resources happens from the rural to the urban and vice-versa creating a harmonious balance between the two factions of the community.

The two fabrics of the rural and urban overlap to create the realm of codependency. A space where neither realm is dominant, a space that serves as a transitory expanse and plays a significant role in the supply chain from one sector into the other. One example of a factor of codependency is that of energy. Energy is a product of the unison of the rural natural resources and raw materials and the infrastructure and technology of the urban. Together they create a tangible flow of resources into the realm of codependency from where the produced energy makes its way back into both sectors.

Another factor that truly embodies rural empowerment is that of trade. Hence, trade becomes the nodal parameter that is a culmination of all the factors of a resilient community. It provides a platform for rural communities to display their skills and allow them to gain economic benefits from the same. In doing so the urban sector is also exposed to the knowledge and cultural values that the rural sector holds and vice versa. This allows for the employment of the rural community in correlation to the urban community through the comforts of their settlements.

The idea of empowerment is not to say that one realm is superior to the other but rather to diminish the disparity between the two communities and facilitate the exchange of knowledge, and resources and aid the growth of both sectors.

11. WELCOME NEW URBAN CITIZENS

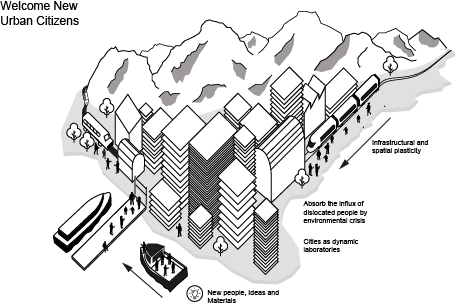

“Our unfolding climate emergency along with political conflict and economic deprivation has already displaced more than one hundred million people worldwide. In the foreseeable future, either by immediate impact or a cascade of secondary effects, climate change will render vast regions of the world uninhabitable. We must use our ingenuity as designers, builders, and policymakers to anticipate the influx of those dislocated by environmental cri sis, to engineer the spatial and infrastructural elasticity that our cities will need—in political spirit and as constructed dwelling space—to absorb this new influx of people and the ideas and materials they bring with them. Cities are dynamic laboratories. They are the dense spatial settings within which a regenerative future will be imagined, tested, and negotiated. They must offer the necessary elasticity to absorb the natural transiency of people, ideas, materials that will be necessary to cope with the dire challenges our civilization faces. They are the sites in which diversities of human aspiration, background, and vision can catalyze the changes needed to meet the dire challenges our civilization faces.”

Cities play a crucial role in welcoming and supporting people whose impacts of climate change have displaced. Climate change and other environmental factors have already caused the displacement of more than one hundred million people worldwide, and many more will likely be affected in the future as vast regions of the world become uninhabitable.

To address this crisis, cities need to anticipate and prepare for the influx of displaced individuals. This includes providing the necessary infrastructure and resources to absorb and accommodate these people, such as housing, transportation, and access to essential services. Cities must also be flexible and adaptable to meet these individuals’ changing needs and accommodate the ideas and materials they bring.

Moreover, cities must be places of diversity, where people from different backgrounds and visions can come together to address the challenges of climate change. By fostering a sense of community and collaboration, cities can help catalyze the changes needed to build a more sustainable and resilient future.

Overall, cities have a vital role to play in welcoming and supporting people displaced by climate change. By providing the necessary resources and fostering a sense of community and collaboration, cities can help to create a more sustainable and resilient future for all.

12. REDEFINE BEAUTY BY BUILDING WITH LOVE AND COMPASSION FOR HUMANS AND NON-HUMANS ALIKE

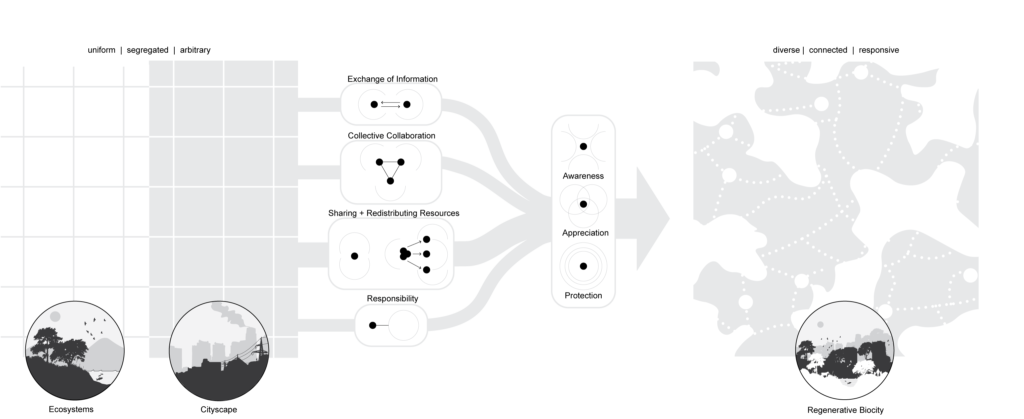

“Regenerative building—the cityscapes it creates and the ecosystems it seeks to restore—will demand an unprecedented exchange of information, our collective collaboration, responsibility, and resolve, and our willingness to share and redistribute resources. If cities are to be our true catalysts for change, then they must incorporate broad awareness, appreciation and protection of the often remote and unfamiliar landscapes and species that comprise the only planetary home we know. It is an opportunity to redefine and entrench a new sense of beauty and joy in the making and experience of our buildings and cities—for the people and non-people who inhabit our Earth. “

Diagram made by Julia Guzmán & Jackie Williams

The last point of the Charter for the City and the Earth concludes with the all encompassing goal of “Redefining Beauty with Love and Compassion for Humans and Non-Humans alike”. It implies that our current view of beauty is based on an industrialized standard of perfection supported by an extractivist approach towards “newness” of freshly extracted building materials coming from segregated sectors. The paragraph wants us to redefine this status quo, by a change of thought and perception, and initiate collaborative approaches that embrace diversity beyond the anthropocentric realm. Through collective action, we need to change these current associations of beauty so that our building processes can become regenerative towards cityscapes and ecosystems, and build respectful relationships with all species on this planet. To develop and entrench the new sense of beauty, it can be fruitful to question the “hegemony of the eye” which sometimes “separates us from the world” and instead embrace the whole spectrum of our senses to “unite us (again) with it”(Juhani Pallasma).

The charter’s paragraph also shares how love and compassion towards humans and non-humans alike is a catalyst to awake our awareness, appreciation and protection towards our environment and companions. Our willingness to shift our current standard and approaches is key to mitigating the current climate crisis. An example of this redefinition comes from British professor Heather Viles and her research on Linking Life and Buildings in the Anthropocene – she states that “for successful integration of life with buildings we should minimize bio-deterioration and maximize bio protection through accepting more bio-cover”.

Conclusively, when our building processes are guided by love and compassion towards all species and landscapes, there is an immense regenerative power in our actions that can maintain a balance in our shared ecosystems.