We have chosen this scene from Dune Part One as a partial illustration of some of the points raised in scholar Stephanie Wakefield’s essay ‘Critical urban theory in the Anthropocene’ and ‘Dreaming in the Back Loops’, where she unpacks resiliency as a multifaceted and reactive approach to surviving life in the urbicidal conditions of the Anthropocene. We believe the scene we chose makes clear Wakefield’s following points:

a) that urban governance is no longer about long-term planning but about navigating endless emergencies through experimental, flexible management, often without critical reflection on why we govern;

b) that infrastructure is deployed incrementally, not to eliminate risk, but to make the policrisis survivable— performative tools for maintaining a sense of control;

c) that the climate crisis is not just a natural force but an organizing logic—reshaping cities, behaviors, and politics into an everyday state of crisis-ready urbanism.

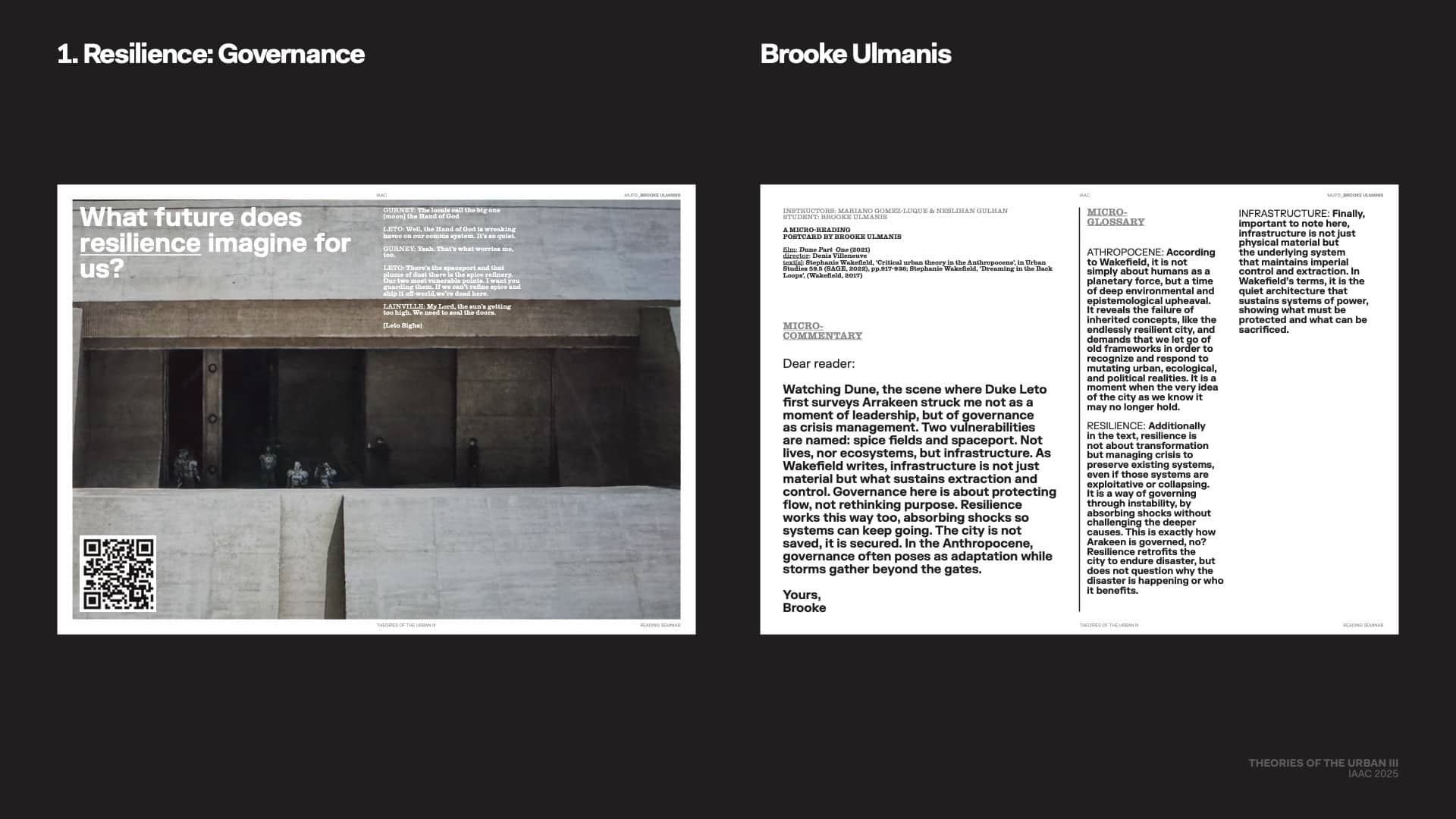

In this scene from Dune, Duke Leto arrives on Arrakis and surveys the city with Gurney. His first act of governance is not visionary but defensive. He focuses on preserving the present rather than imagining a new future. This reflects what Stephanie Wakefield calls governance as crisis management. Leadership here is not about transformation but about navigating constant emergencies linked to the policrisis.

Leto identifies the spice fields and spaceport as the city’s most vulnerable infrastructure points. These inherited systems are not questioned, only secured. His job is to keep things running, not to rethink how or for whom they work. Wakefield connects this to resilience — not as change, but as the ability to absorb shocks so existing systems can survive. Leto maintains a fragile status quo, ensuring the spice keeps flowing, no matter the cost.

This mode of governance belongs to the Anthropocene, a time defined by overlapping crises. In this context, to govern is to adapt, not to imagine alternatives. Leto isn’t leading toward a better future. He’s preparing for the next disaster. When resilience defines governance, the city is not saved. It is merely secured.

—

Resilience, not just as a design principle or a way to govern but as an environmental trap. Our focus is on how climate resilience, particularly in the context of this film, reveals deeper logics of control and delayed transformation. We discussed it through Wakefield’s critique of resilience and connected it with Brenner and Schmid’s notion of planetary urbanization.

In the scene where House Atreides arrives on Arrakis, we see a city engineered for survival: thick walls, shaded corridors, shutters that close with the rising sun, a shield wall to guard against the desert. At first, it looks like a smart response to a harsh environment, an example of environmental resilience. But we started discussing if this is resilience, or actually a form of environmental domination. They’re not learning to live with the desert, they’re keeping it out. That’s exactly Wakefield’s point. Resilience can look like responsibility, but often it just means delaying real change. It protects what already exists (cities, infrastructure, hierarchies of power). And that’s what the Atreides are doing while not rethinking how they relate to the planet, they just build better defenses.

Even the Fremen are seen as people who adapt in this harsh desert as radical survivors, aren’t totally outside of this logic. Their adaptation might be real, but it’s also a form of control: efficient, secretive, militarized. And once Paul steps in their lives, their desert resilience is mobilized into a messianic empire. So are they truly an alternative or just another version of the same planetary system?

Brenner and Schmid say that urbanization is now planetary, it’s not a place, but a condition. The desert, the fortress, the supply chain are all part of the urban fabric. That’s powerful, but also dangerous. If everything is urban, is resistance even possible? Or do all alternatives just become new layers on the same structure? That’s where the idea of the urban palimpsest comes in, Arrakis isn’t a blank slate but a site where every form of domination leaves its trace. Every “solution” becomes part of the next problem. So Wakefield’s challenge is: what if we stop thinking about resilience as preserving what we have? What if we made space not for utopia, or control but for reconfiguration? For undoing. For not knowing.

So maybe our final question isn’t how to survive, but what forms of harm are we willing to accept to preserve the world we know? Because if we keep optimizing and defending systems that are already broken, then urban theory and maybe even urban design risks becoming a quiet partner in slow violence. But if we shift from fixing things to exposing them, maybe we can start unbuilding what no longer serves us. Not because we know what comes next but because we finally admit we don’t.