For the class exercise, the topic that caught my attention the most and felt the most important was mitigation vs. adaptation. It stood out because it shows two different ways of tackling climate change: one that aims to prevent it from worsening (mitigation) and one that helps us adjust to its effects (adaptation). This is particularly relevant in ecological building and design because both approaches influence how we shape the built environment. Mitigation might involve using low-carbon materials or designing energy-efficient buildings, while adaptation could mean preparing for rising temperatures, floods, or water scarcity. Understanding both gives architects and designers the tools to create spaces that not only reduce environmental impact but also protect and support the people who live in them as the climate continues to change.

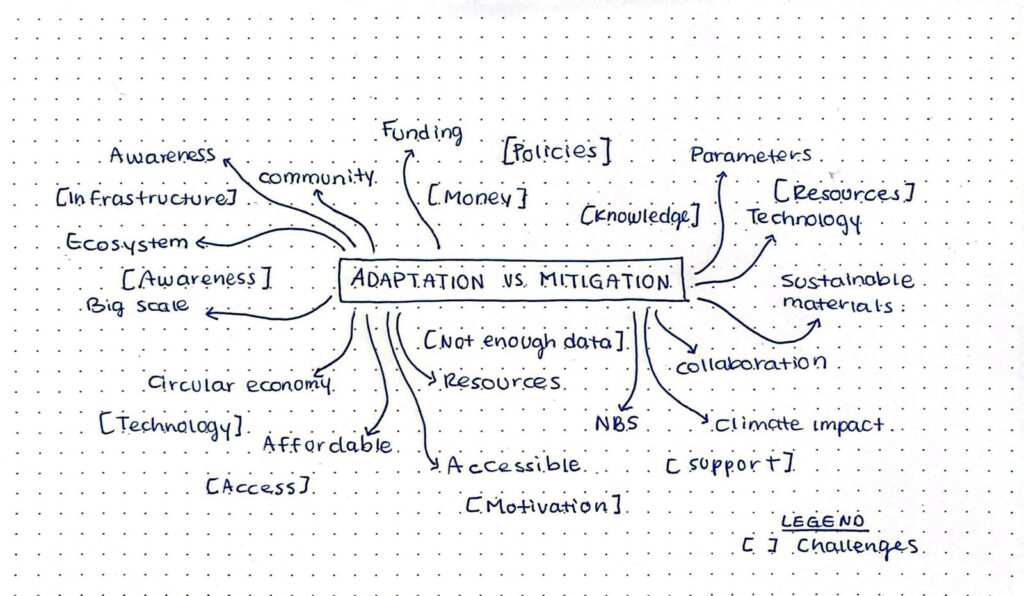

MAP

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES:

A few of the main challenges with adaptation and mitigation strategies are financial constraints. These strategies tend to be large-scale, so they require significant investment to work properly. The issue is that not every country has the resources to make this happen, especially governments already under pressure. Another big challenge is the lack of awareness and unwillingness of both people and governments to act. Climate action often depends on public support, but some solutions can feel inconvenient, expensive, or unnecessary, so they don’t always get the backing they need. There’s also the problem of not having enough local data. Since most strategies need to be customized for specific areas, it’s tough to design the right solutions without fully understanding how climate change is affecting a particular place. This is especially important in ecological building and design, as we need that local information to build in a way that works for both the environment and the people living there.

On the other side, there are some real opportunities here. These strategies can help people on both small and large scales, from individuals and local communities to the planet as a whole. When cities switch to renewable energy, improve public transport, or design energy-efficient buildings, it lowers emissions everywhere, not just in that one area. The same goes for adaptation—when communities prepare for things like floods, droughts, or heatwaves, they’re not just protecting themselves, they’re also creating systems and knowledge that can be shared and applied elsewhere. These actions add up and can spark global shifts in how we address climate change. It also opens up opportunities for countries and cities to collaborate, share ideas, and push for policies that create a bigger impact. So, while these changes might start small, they can snowball into something much bigger, benefiting the planet in the long run.

CONNECTION TO THE OTHER TOPICS

When I compare adaptation and mitigation with vernacular architecture, I see a lot of common ground. For one, both work with local resources and the environment. Vernacular architecture has always been designed to fit its surroundings, using materials and techniques that suit the area’s specific conditions. Similarly, modern adaptation and mitigation strategies focus on creating solutions based on local climate data. Both approaches respond to environmental conditions and share the goal of sustainability, relying on local resources and knowledge to make the most of what’s available.

However, there are also some clear differences. Vernacular architecture is deeply tied to cultural practices and local knowledge, reflecting the values and way of life of the community. Adaptation and mitigation strategies, on the other hand, are often shaped by scientific research and technological advancements. Vernacular architecture tends to evolve organically over time, built on trial and error, while modern strategies are often driven by global policy frameworks and data-driven approaches. Another difference is that vernacular buildings focus on blending with the natural environment, relying on passive systems to regulate temperature and energy use, whereas contemporary adaptation and mitigation strategies often involve active systems, such as renewable energy technologies or climate modeling, which need ongoing maintenance and resources