//MY INITIAL VIEW

When I first began using AI-related tools in architecture and the built environment, I approached them primarily as a tool for efficiency. My focus was on faster modelling, optimization, and the ability to test more options in less time. AI, to me, was something applied after a design idea existed, a way to optimize what I had already decided.

However, as the course progressed, and as I engaged more with lectures, datasets, and listened to people experienced first hand real-world case studies, my understanding of AI in AEC shifted significantly. I began to realize that AI’s most impactful role is not in accelerating design output, but in reshaping the basis on which design decisions are made.

The emphasis moved from “What can I generate?” to “What should I be responsible for?”

//HOW MY VIEW ON APPLYING AI IN AEC SHIFTED

One of the biggest changes in how I work came when I stopped using AI to generate forms and started using it to understand the consequences of my decisions.

Before, I often relied on instinct — choosing a roof shape or massing because it ‘felt right’ spatially or visually. But once I began working with environmental analysis tools, I realized how much information I was previously designing without. AI-driven simulations could process thousands of data points at once — sun exposure, heat accumulation, airflow, daylight — things that would be almost impossible to grasp manually.

When I tested different roof and massing options, the results were no longer abstract. I could see, in numbers and diagrams, how one decision led to more overheating, how another improved daylight but increased material use, or how a small change in orientation dramatically affected comfort. Suddenly, design choices had consequences that were hard to ignore.

AI didn’t tell me what the right answer was. But it removed the comfort of vague intuition. It made trade-offs visible, and once they were visible, they became my responsibility. As a result, my design moves became less arbitrary and more intentional, grounded in evidence, but still guided by human judgment.

GIF by Infrared.city

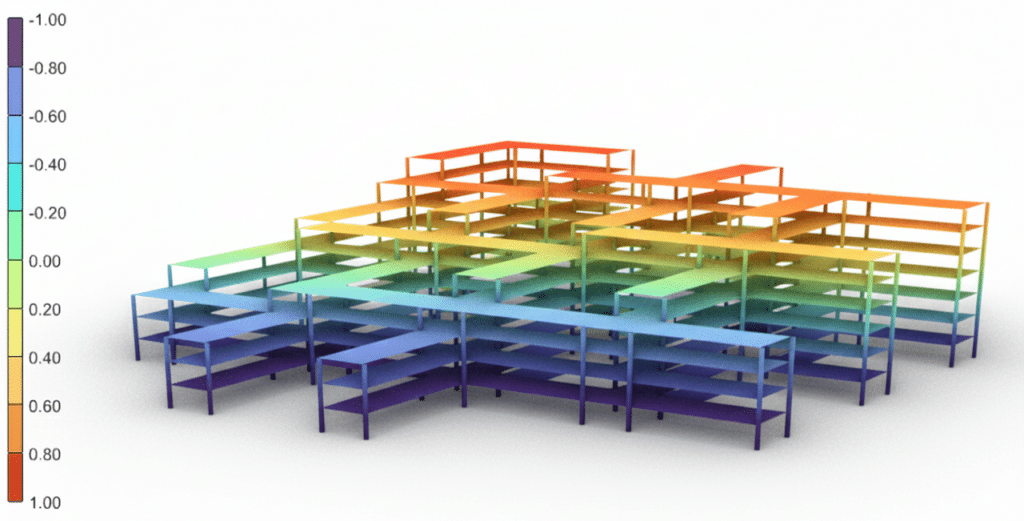

In the Environmental Analysis course, automation gave me was not just speed, but consistency and clarity. Every design change immediately produced comparable radiation results, making it impossible to ignore the environmental impact of even small formal decisions like placing greenery.

One of the guest that was invited to our lecture was Libny Pacheco, he further shifted my thinking by bringing AI directly into the design domain through data-driven urban analysis. His classification model identifying flood-prone street intersections in Stockholm during a 100-year flood event showed how AI can transform abstract climate risk into spatially precise design intelligence. Rather than generating architecture, hence, AI guides where architecture must respond.

‘100-Year Flood Risk Road Intersection Classification’ by Libny Pacheco for IAAC

//AI AS A QUESTION GENERATOR, NOT AN ANSWER MACHINE

A critical turning point for me was realising that AI is most powerful when it raises questions rather than provides solutions. When presented with simulation outputs, probability maps, or performance comparisons, I found myself asking:

- Why does this area consistently overheat?

- What assumptions am I making about occupancy or behaviour?

- Which design variables actually matter, and which are cosmetic?

This process forced a more reflective design practice. Instead of treating AI outputs as final answers, I learned to treat them as prompts for responsibility.

Recognizing this clarified my own role as an architect. My responsibility is not diminished by AI — it is intensified. AI does not replace human thinking; instead, it expands the boundaries of what human thinking can engage with. By processing vast amounts of information, identifying patterns, and revealing relationships we could never manually detect, AI opens up territories of understanding that previously felt inaccessible.

What changes, then, is not the need for human judgment, but the level at which that judgment must operate. AI can surface possibilities, risks, and consequences, but it cannot decide what matters. It cannot prioritise care, ethics, cultural meaning, or social impact. The act of translating data into spatial decisions — deciding what to respond to, what to ignore, and what to value — remains fundamentally human.

Examples of information that personally I could never manually detect myself

//MY EXPECTATIONS FOR THE FUTURE OF AI AND AUTOMATION IN AEC

Looking forward, my expectations for AI and automation in AEC are very practical. I don’t see them as tools to replace designers, but as ways to protect time, accuracy, and focus in an increasingly demanding profession.

In practice, many of the most time-consuming tasks in architecture and environmental analysis are also the most vulnerable to human error — especially under pressure. Manual data input, repetitive simulations, drawing coordination, and re-running analyses after small design changes are not only slow, but also risk becoming inaccurate when deadlines are tight or when multiple projects overlap. Automation has the potential to remove this fragility from the process.

What I expect AI and automation to do is take over repetitive and rule-based tasks: running environmental simulations consistently, updating analysis when geometry changes, checking performance metrics, and flagging issues early. This doesn’t just save time — it creates reliability. When analysis is automated, results are less dependent on whether someone is tired, rushing, or switching between too many projects.

By reducing the manual workload, AI frees up time for the parts of architecture that cannot be automated and related to the ‘soul’ in a project: critical thinking, spatial judgment, ethical decision-making, and communication. Instead of spending hours redoing the same analysis, architects can spend that time interpreting results, discussing alternatives, and designing more responsibly.

Ultimately, my expectation is that AI and automation will help shift architectural practice away from firefighting and toward intentional design. Not by making us faster for the sake of speed, but by making our decisions more consistent, accurate, and defensible — even under real-world pressures.

Things that automation did that saved time during term 1