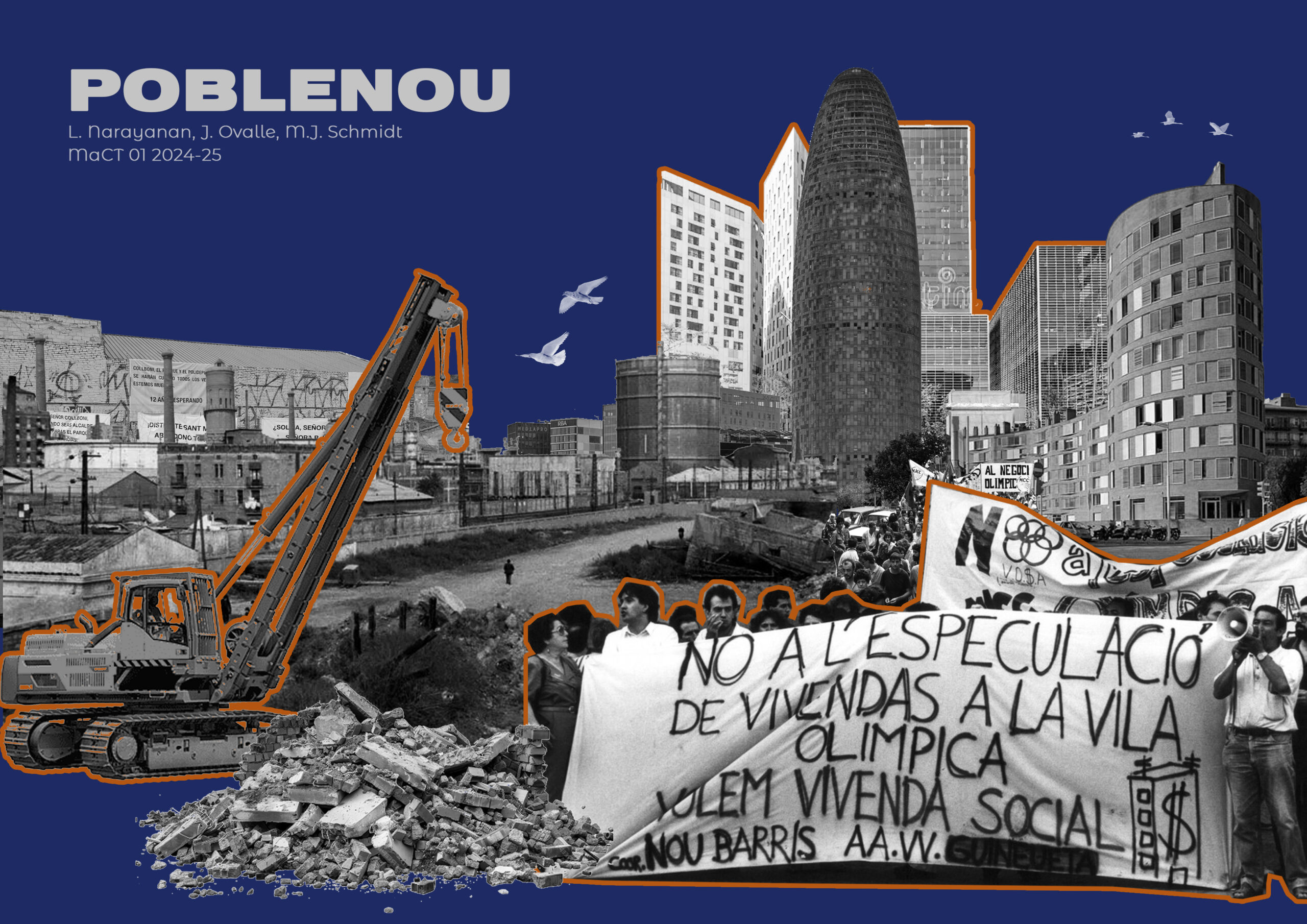

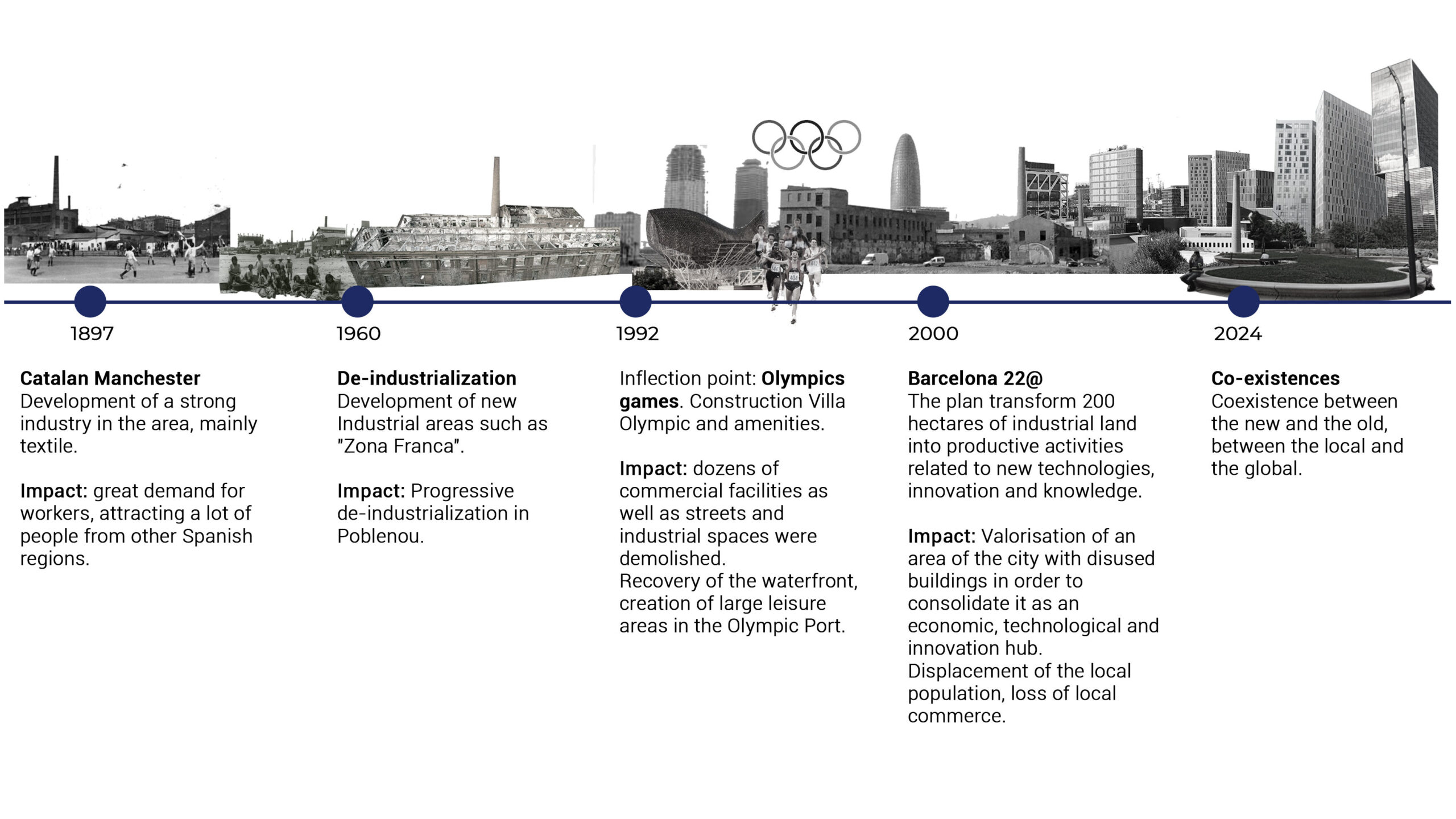

The urban transformation of the Poblenou neighborhood has reached a critical juncture, where the local and global spheres coexist in a contested struggle over territory. The revitalization of old industrial buildings into a technological and creative hub has spurred significant economic growth, attracting a wave of companies, start-ups, investors, and, more recently, digital nomads, displacing local inhabitants.

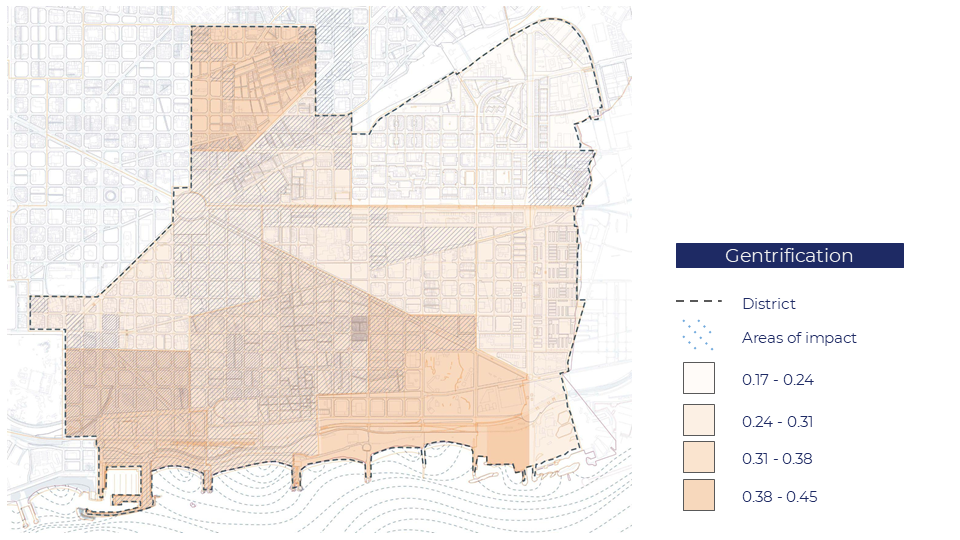

Through this activity, we could collect and analyze theoretical and empirical data, regarding the economic and social impact of the Olympics games and the 22@, in the study area. The goal of this exercise is to visualize the impacts in the daily life of the local community as a result of the gentrification process.

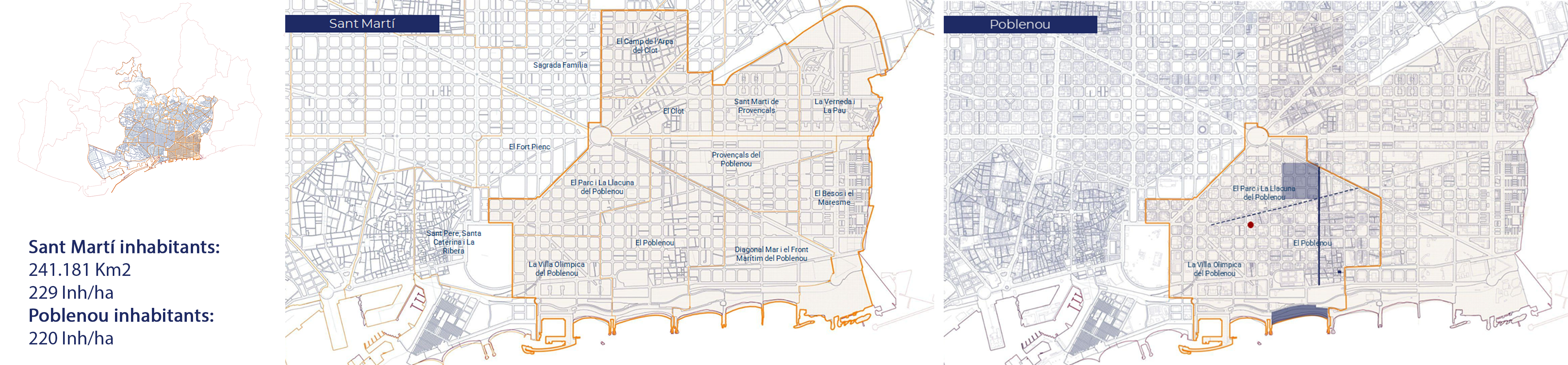

Poblenou is located in the district of Sant Marti. Besides the well known buildings, the neighborhood is distinguished by the Rambla of Poblenou, the Olympic Villa and the first Superilla built in Barcelona.

Along the route, we could observe different kinds of areas. In the boundaries of the neighborhood and close to Gloria’s park, the more commercial and economical area. Over the Pere IV avenue the Poblenou’s industrial past, where despite it’s currently in transition, and under high development pressure, the area is characterized by no residential density, commercial land uses, or pedestrian flows. Around Poblenous’s Rambla, the historic village with high density of residential activity and diverse commercial uses. The path ends in the Olympic Villa area, mostly residential and with the traces of Barcelona 92.

From 1897 a strong industry was developed in this area, mainly textile. This meant an increase in labor supply and the consequent migration of workers. Since then and after the following transformations the population has increased significantly. Nowadays the district of Sant Martí has 14% of the Barcelona population, and less than the 15% lives in Poblenou. From this we can observe that it is an area with low population density, compared to the other neighborhoods.

While this development has improved infrastructure and enhanced the overall quality of life, it has also driven up property prices, rendering the area unaffordable for long-time residents. The uneven distribution of economic activities, coupled with stark contrasts between affluent and disadvantaged areas, has fueled social segregation. Furthermore, the advance of modern architecture has, in many cases, eroded the neighborhood’s traditional identity.

Additionally, as part of the urban renewal process, real estate developments along the waterfront have fragmented land use and exacerbated social division, restricting access to those who can afford the rising costs.

The challenge moving forward lies in how we can reshape our cities to foster economic growth and modernization without sacrificing local identity and community cohesion. The key is to balance the interests of the market with those of the community, creating a scenario where both can thrive. As we rethink urban spaces in a post-pandemic world—where office use has dramatically shifted and work patterns have become more nomadic—we must explore innovative ways to design cities that are inclusive, adaptive, and capable of supporting both local residents and global participants in a sustainable, equitable manner.