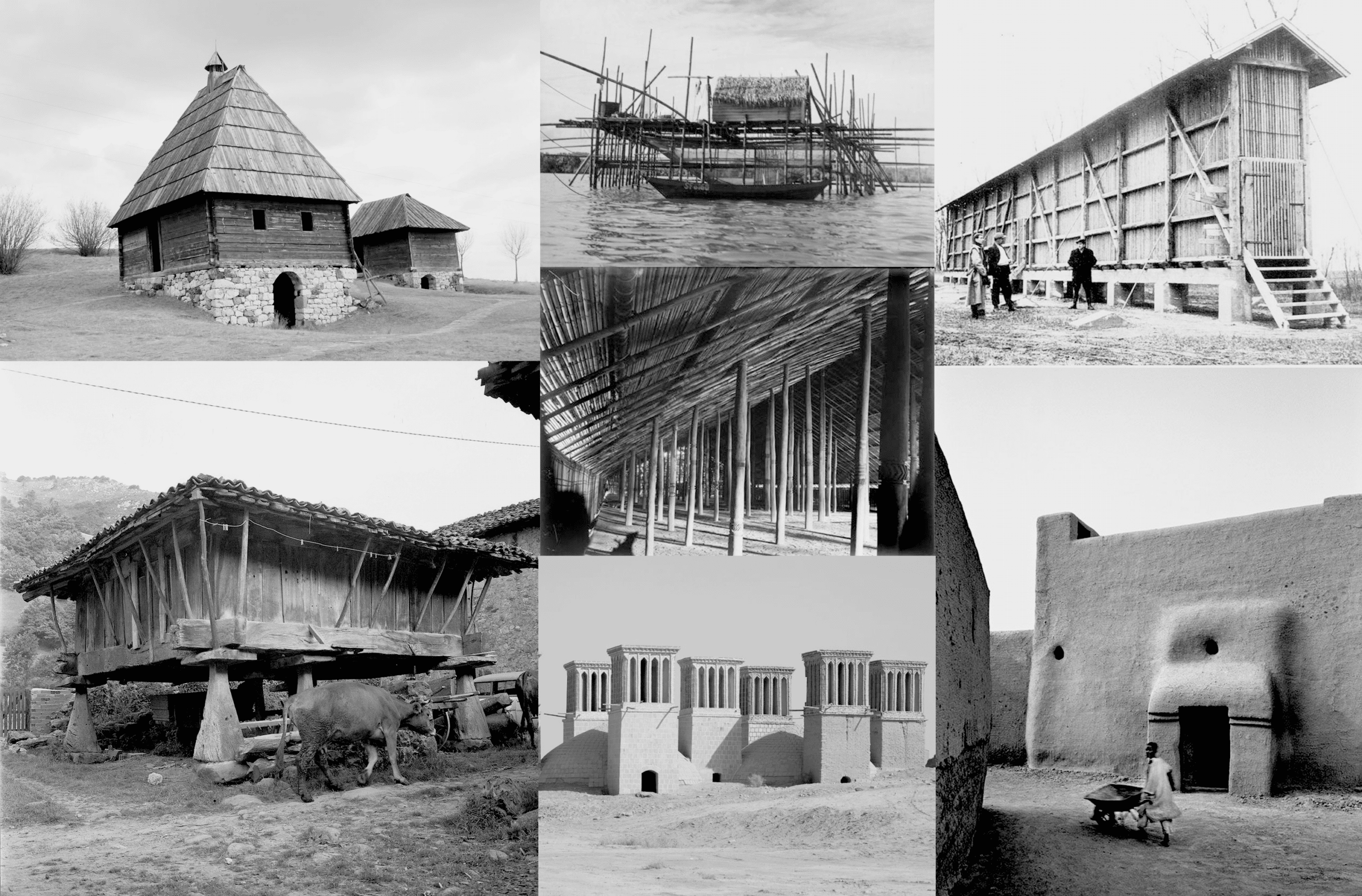

Of all the topics explored in our Ecological Intelligence seminar—ranging from urban greening to multispecies design—vernacular architecture stood out as the most quietly radical. Its intelligence is not flashy or algorithmic. It doesn’t require parametric software, biofabrication labs, or climate dashboards. Instead, it draws from generations of lived experience, calibrated to the rhythms of place, material availability, and climate.

What makes vernacular architecture compelling is not just its sustainability—it’s the fact that it never needed to be called sustainable in the first place. It simply was. In a world increasingly reliant on high-tech “solutions” to ecological crises, vernacular architecture offers a kind of deep ecological memory, reminding us that many of our most pressing design challenges have already been addressed—just in ways we’ve largely forgotten.

The opportunity of vernacular design lies in its responsiveness. From thick adobe walls in arid zones to stilted homes in humid climates, vernacular buildings encode sophisticated passive strategies. These are designs that breathe with the landscape, that adapt across seasons, and that derive their form from material logic rather than stylistic trends.

But vernacular design also presents real challenges—especially when it is lifted from context. As I noted in my reflection on Ahmet Eyüce’s paper (Learning from the Vernacular: Sustainable Planning and Design (Open house international Vol 32, No.4, December 2007)), contemporary architecture often risks appropriating vernacular forms without understanding their underlying ecological logic. Without deeper analysis—thermal performance metrics, orientation studies, or socio-cultural embeddedness—we risk turning vernacular strategies into aesthetic gestures.

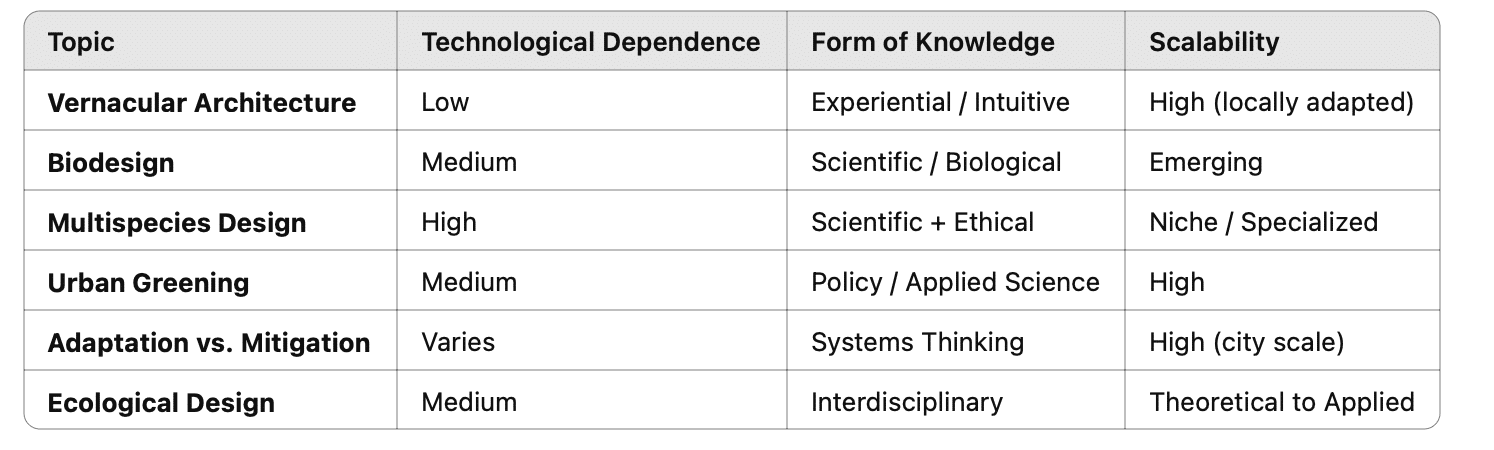

Vernacular architecture resonates strongly with several other themes we’ve explored this term, particularly in contrast to technocratic or heavily mediated approaches. For instance, in the second week, I critiqued the technocratic bias in multispecies architecture—a field that, while ethically compelling, too often depends on top-down expertise and high-budget implementation. Vernacular strategies, by contrast, emerge from ground-up knowledge systems and can serve multispecies needs without the need for complex toolkits.

Similarly, in the third week’s discussion of biodesign, the idea of resilience through adaptation mirrored vernacular logic. The difference lies in the medium: biodesign looks forward to engineered biomaterials; vernacular looks back (or perhaps sideways) to locally available, often biodegradable ones. Both seek to dissolve the boundary between built form and living system—but one does so with lab-grown mycelium, the other with straw and clay.

The Following Table Expresses a mapping of the various topics described this term and their relationship to technology, how they uptake knowledge, and their ability to be scaled.

We talk a lot about the future of architecture. But maybe the real question is: what futures have we already abandoned? Vernacular architecture points to a kind of intelligence that doesn’t overly rely on smart sensors or highly carbon intensive built up skins to buildings. It reminds us that true ecological design isn’t always about innovation—it’s about listening.