The third and final volume of the Theories of the Urban Seminar has taken science fiction as both a critical framework and a mode of spatial representation, using cinematic and theoretical lenses to examine urban futures in the Anthropocene. Where previous volumes addressed urbanization as historical concept and financial phenomenon, this installment confronts our planetary urban reality through speculative fiction’s estranging gaze.

Across four sessions, we’ve engaged films and texts that map possible futures – from algorithmic governance to socio-ecological collapse – treating SF not as prediction but as a form of ecological critique. This approach culminates in what we’ve come to call theoretical postcards: concentrated group analyses that distill complex urban futures into vivid film fragments. Like postcards from alternate realities, these micro-readings – whether examining a single shot from Children of Men or a sequence from Blade Runner – serve as both warnings and invitations. They compress our seminar’s key questions into urgent, performative encounters with the urban imagination.

The result is neither conventional film analysis nor detached theory, but a lived engagement with speculative fiction’s power to defamiliarize our present. These postcards don’t just represent ideas – they perform them, making visible the latent trajectories in our contemporary urban condition.

Keeping with the seminar’s focus on speculative urban futures, our film selection represent the seminar’s core themes. Children of Men stands out in this regard—its dystopian vision collapses speculative fiction into critical theory, rendering visible the latent trajectories of planetary urbanization, cultural memory, and architectural power.

The film evokes Gerry Canavan’s concept of cognitive estrangement—estrangement—namely, the

defamiliarization of our historical

reality. It forces us to view the present

through a different cognitive framework.

The dystopia portrayed is a plausible

future, which makes this estrangement

especially effective: one can draw a clear,

rational link between the on-screen world

and our own.

In order to illustrate this topic we choose a the most representative scene. We believe the scene we chose makes clear the following points:

a) carnival of brutality in the planetary urbanization era where the outside-inside merge in chaos ; b) shared

archive of artistic narratives open cracks toward alternative futures; c) architecture can be seen as the narrativization of transnational elite’s desires.

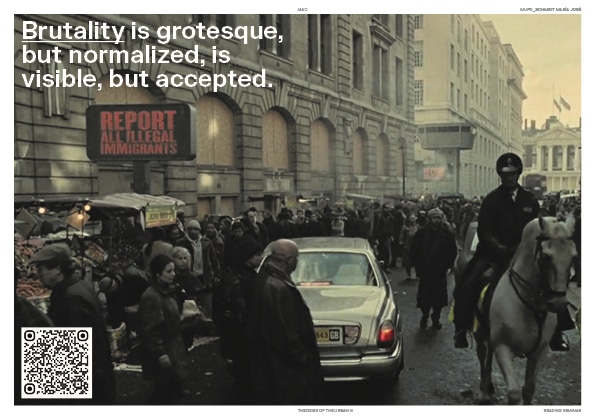

Carnival of brutality

We can read the movie as an ecological critique, of a world that has collapsed, we don’t see what happened, what was the point that denoted the disaster. But we can see how the brutality of the system is exposed in a grotesque way, but normalized.

In this scene we can follow Theo inside a luxury car through London city.

Outside, we can see the material and spatial dimension of what B and S describe as planetary urbanization, a condition where the dialectic urban-non urban, inside-outside started to blur.

We can see how the movie brings all together into the center of London. The cars continue, and we can see how coffee bars and internment caps operate side by side. We see poverty on the street and rich people walking by with their zebras and camels in the park. Here, the public space works as a facilitator to surveillance, segregation and exposure.

But I think the most controversial thing in the movie is that all of this brutality happens while democracy is still proclaimed. It seems that the normalization of the crisis leads people to live under democratic system with most of their rights and freedom suspended.

The car arrived, passing through buildings that were once public entities, and now are surrounded by military force.

This is what Mark Fisher calls a carnival of brutality: a grotesque coexistence of state violence, ecological decay, and social injustice. Everything is visible. And no one is shocked.

The dystopia of late capitalism is already here and is deep inside our minds.

Capitalism hinders our capability of imagining alternative and different futures outside of the neoliberal framework. It stands as an immovable horizon. It really feels like we are having an imagination crisis.

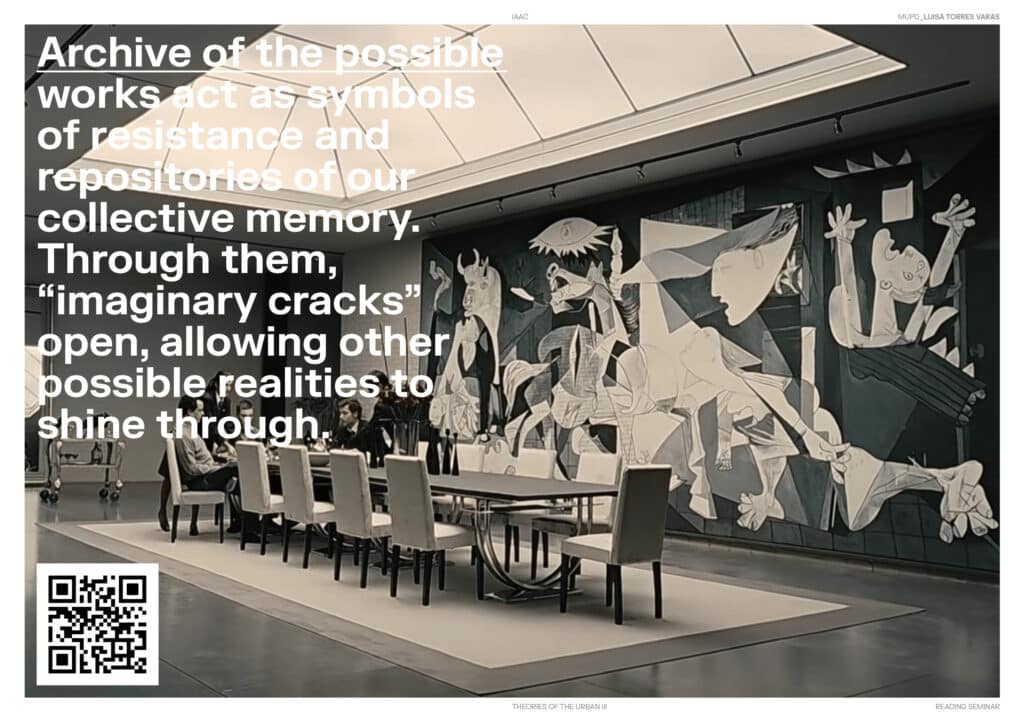

Additionally to this, we can also see the privatization of art—locking these cultural legacies—causes communities to lose access to their own symbols of resistance, fragmenting and impoverishing collective memory.

Collective memory in the film played a huge role, since the only moment in which war stopped is when the baby was seen by people, including soldiers, and collective memory was activated; it really is incredibly powerful.

To this cultural legacy, Gerry Canavan calls it the “archive of the possible.”

This art is a medium for critical consciousness, just as this SF movie opens space for this apocalyptic critique. It pushes us to think in radically different scenarios.

Through the archive of the possible, “imaginary cracks” open, allowing other possible realities to shine through.

In this scene, we can see Picasso’s “Guernica,” which, once a cry against horror, is now a canvas without context or function—it is no longer a living organism that reinvents itself, but a corpse preserved for admiration without being understood or altered. The piece of art is totally alienated just as its own owners. Tradition only makes sense if the present challenges and reconfigures it.

End of Architecture as ‘Social Art’.

“I just don’t think about it”

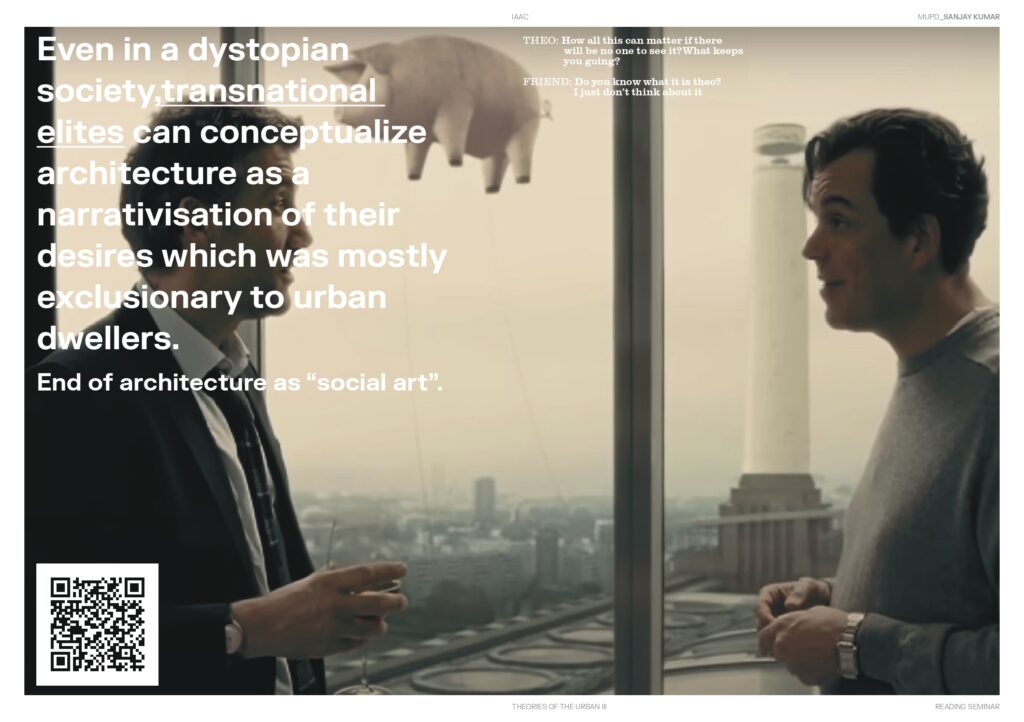

Was the last sentence of this scene spoken not in the chaos of the outer world, but in a serene, glass-wrapped haven inside his secured art collection treasury.

In this scene theo friend nigel character express as a perfect example of what maria Kaika and urban theorists call “transnational elites.”who has a major role in shaping the city, but does not live in it.And also The scene implies the same when nigel invites theo with his hand to look at the city from above metaphorically express that He commands the city from above—quite literally in a luxury tower never from the street.

This space where the scene was happening reminds me of Maria Kaika’s concept of “autistic architecture.” where kaika argues that architecture has shifted from being a “social art” to becoming a self-centered elite fantasy, disconnected from the city’s actual needs.

So what does it mean when architecture stops listening? When buildings no longer serve people, but performance? When glass becomes a wall, not a window?

End of Architecture as ‘Social Art’.

Also his attitude of self centered interior spaces extends to the open space around these buildings.Finally, we must talk about what Francesco Sebregondi calls “exclusionary design.”The transformation of places like Battersea from industrial commons into luxury vaults isn’t accidental. It’s a spatial tactic.

Exclusion isn’t a bug in the design—it is the design

So the movie Children of Men, the apocalypse It’s a slow forgetting of child crying.

It can be related to the A forgetting of the city, of public space, of parks,shared community space

And this forgetting is built brick by brick—by elites who

“just don’t think about it.

Children of Men, if we think about it, would become a way worse dystopia if we add AI. Just imagine the surveillance level that there would exist. What is interesting to us now is how AI is already altering our cognition, as Katherine Hayles has mentioned. This can be seen in parallel to how critical consciousness is being affected by the privatization of art, and now of knowledge, since ChatGPT reads an amount of text based on how much you pay.

We read the infertility in the movie, as Mark Fisher suggests, as a cultural crisis—as a critical consciousness infertility. But this one is not happening since a specific generation or year, as infertility happened in the movie. This one is like a virus that affects everyone who uses AI in a non-critical way, starting to change the architecture of our brain.