Abstract

Building upon the knowledge acquired in the Agent-Based Design & Machine Learning course, we developed a bot designed to collect data from the population of Rundu, the city we are focusing on for our project within the Vulnerability Studio: Computer-Aided Mobility Justice.

We face the challenge of accessing qualitative insights that could help us better understand the local context due to the fact that we lack visual information (such as photographs) of the area, there are no street views available on Google Maps, and because we are conducting our research from afar we cannot go the site and get the data by ourselves.

To address this, we designed a bot that invites the community of Rundu to share photographs of public spaces along with their suggestions for improvement. This interactive activity allows residents to imagine the potential of their urban environment while providing us with valuable data to conduct research that is both context-aware and as accurate as possible in reflecting the reality of Rundu.

The Urban Context

Rundu, located in northern Namibia near the Angolan border, is undergoing rapid urban expansion driven by rural-urban migration, a young demographic, and a shortage of formal housing. This growth has led to the proliferation of informal settlements such as Ndama, where the inadequacy of infrastructure starkly contrasts with the city’s expanding population.

Informal Urban Growth and Material Conditions

The spatial development of Ndama is largely informal, with 92.5% of households having no official land application. Housing in the area is mostly self-built, with over 85% of roofs and a significant portion of walls made from corrugated iron. These materials offer limited insulation, compounding the discomfort caused by extreme heat. Settlements lack structured urban planning, with scattered multi-household plots, often combining residential and business uses.

Mobility and Surface Infrastructure

Mobility within Ndama is dominated by walking (80.5%), followed by minimal use of taxis and informal private vehicles. The settlement is characterized by sandy and unpaved roads, which severely limit accessibility (especially during the rainy season) and pose serious challenges to movement for women, children, and the elderly. There is a complete absence of sidewalks, road lighting, and drainage infrastructure. These deficits transform simple tasks such as walking to fetch water or accessing schools and clinics into strenuous and hazardous journeys.

The walking times are extended further for elderly or physically impaired residents due to poor terrain and high temperatures. Roads connecting Ndama to central Rundu are partially paved but deteriorate at the boundaries of informal areas, creating a stark physical and symbolic divide between formal and informal zones.

Water and Sanitation Deficiencies

Water access is a daily struggle. Over 60% of households rely on someone else’s private tap, and more than half lack access to any toilet. There are no water lines or sewerage systems in the informal areas, and residents must walk long distances on unstable surfaces to access shared water points. This physically demanding process disproportionately affects women and girls, who are typically responsible for water collection, and who face added burdens during menstruation due to the lack of sanitary facilities.

Gendered Vulnerabilities and Safety Concerns

Rundu’s public spaces are not safe for women, especially at night. The absence of street lighting, isolated paths, and long commuting distances expose women and girls to a high risk of gender-based violence. For female-headed households and residents with disabilities, this lack of safety and infrastructure results in compounded social isolation, limited economic participation, and restricted access to healthcare or support networks.

Problem Statement

Our project for the Vulnerability Studio is being developed from afar, as we are based in Barcelona. Since we are not physically present in Rundu, we must rely on open data available online. However, such data is extremely limited because Rundu is a rapidly growing city with little digital footprint. There are no Google Street View images, and very few photos or videos of the city can be found on social media or other platforms.

This lack of accessible data has posed a major challenge for our studio work. As a result, we identified the need for a tool specifically designed to collect localized information directly from residents, an approach that would allow us to bridge the gap and work with more grounded, community-informed data.

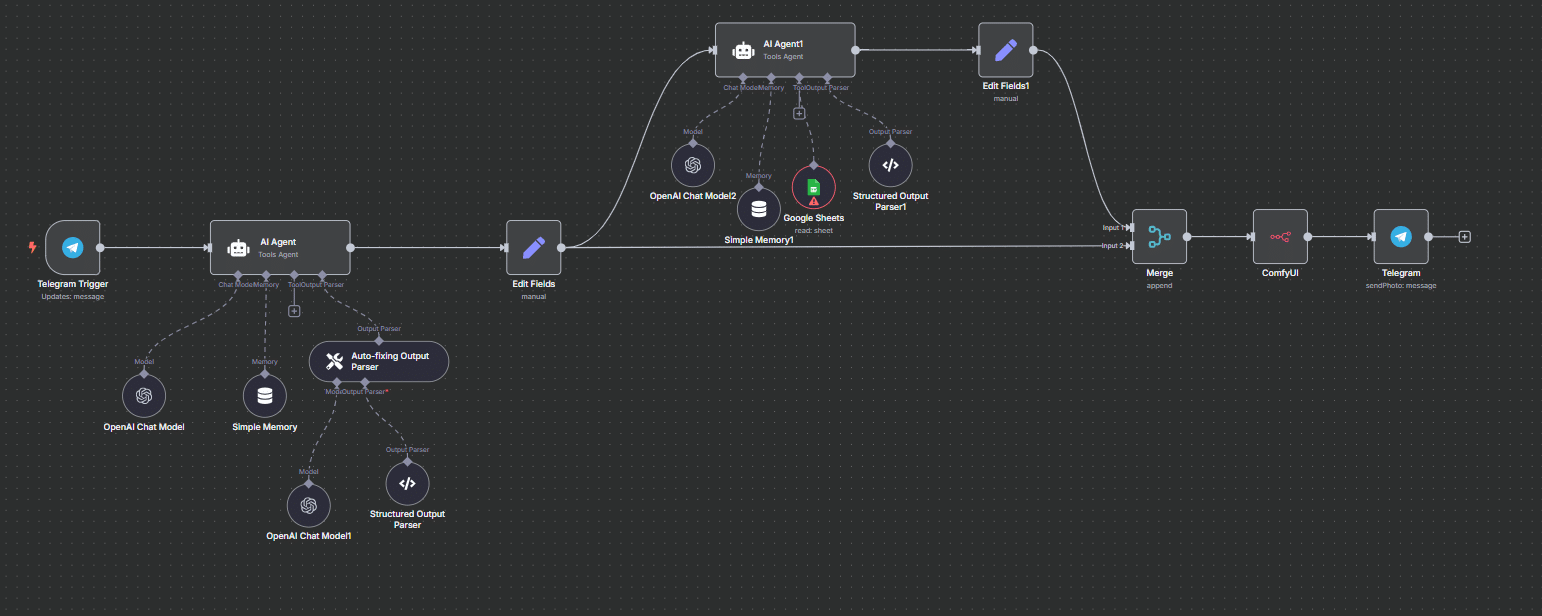

Our team at the Vulnerability Studio seeks an effective method to collect qualitative data from Rundu while working remotely from Barcelona. This approach should integrate automation tools such as n8n, and potentially include conversational bots, AI agents, ComfyUI for image generation, and access to data sheets. The goal is to enable a bottom-up data collection process that captures a more accurate understanding of how public space is perceived by the local population in Rundu.

Bot Development

To achieve our objective, we decided to develop a bot that interacts directly with the population of Rundu. This bot is designed to collect both data and prompts regarding how residents believe public spaces, and their experience of commuting to collect water, could be improved. At the same time, it offers participants the opportunity to visualize these imagined scenarios, helping them reimagine their surroundings while contributing to the co-creation of more inclusive urban spaces.

DATA COLLECTION – Part 1

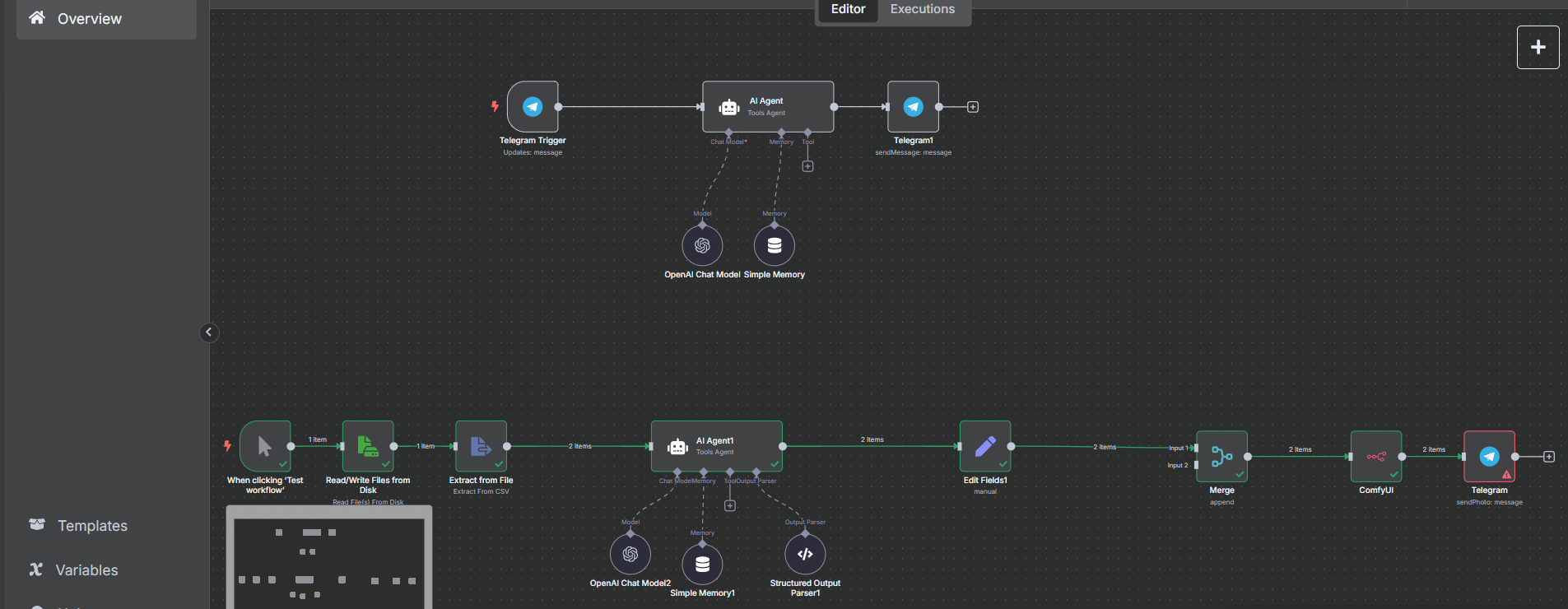

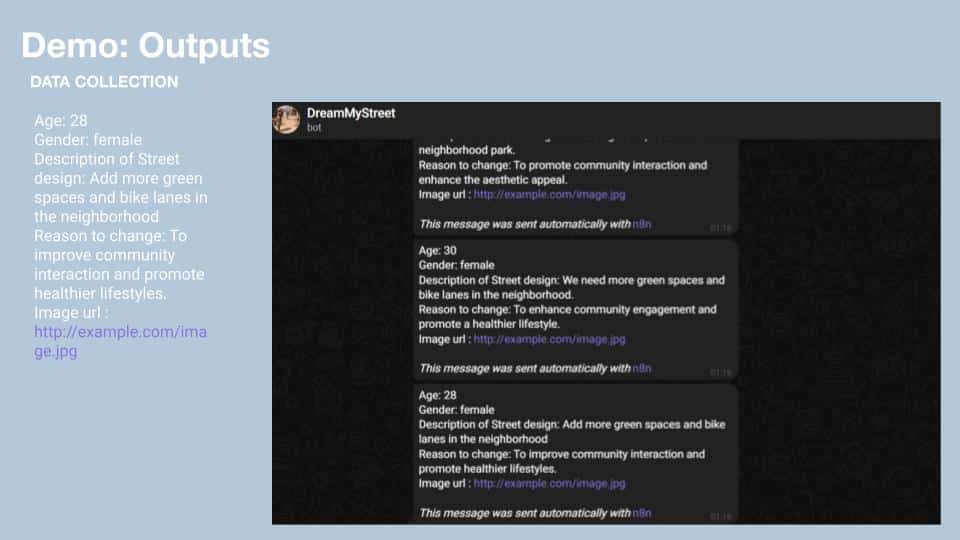

Establishing the AI chatbot which pretends to be a urban planner who collects all the data and stores in a excel.

Bias/ Difficulties:

The Telegram chat bot is established through cloudflare tunneling but the google sheets api doesn’t allow cloudflare tunnel to access data.

DATA COLLECTION – Part 2

Creating a prompt through the prompt engineers (AI) using the requests collected through the interviews.

Bias/ Difficulties:

The AI is creating a prompt on behalf of the humans. There is certain bias or generality in the prompts generated.

Bot Functioning

DATA COLLECTION – Part 3

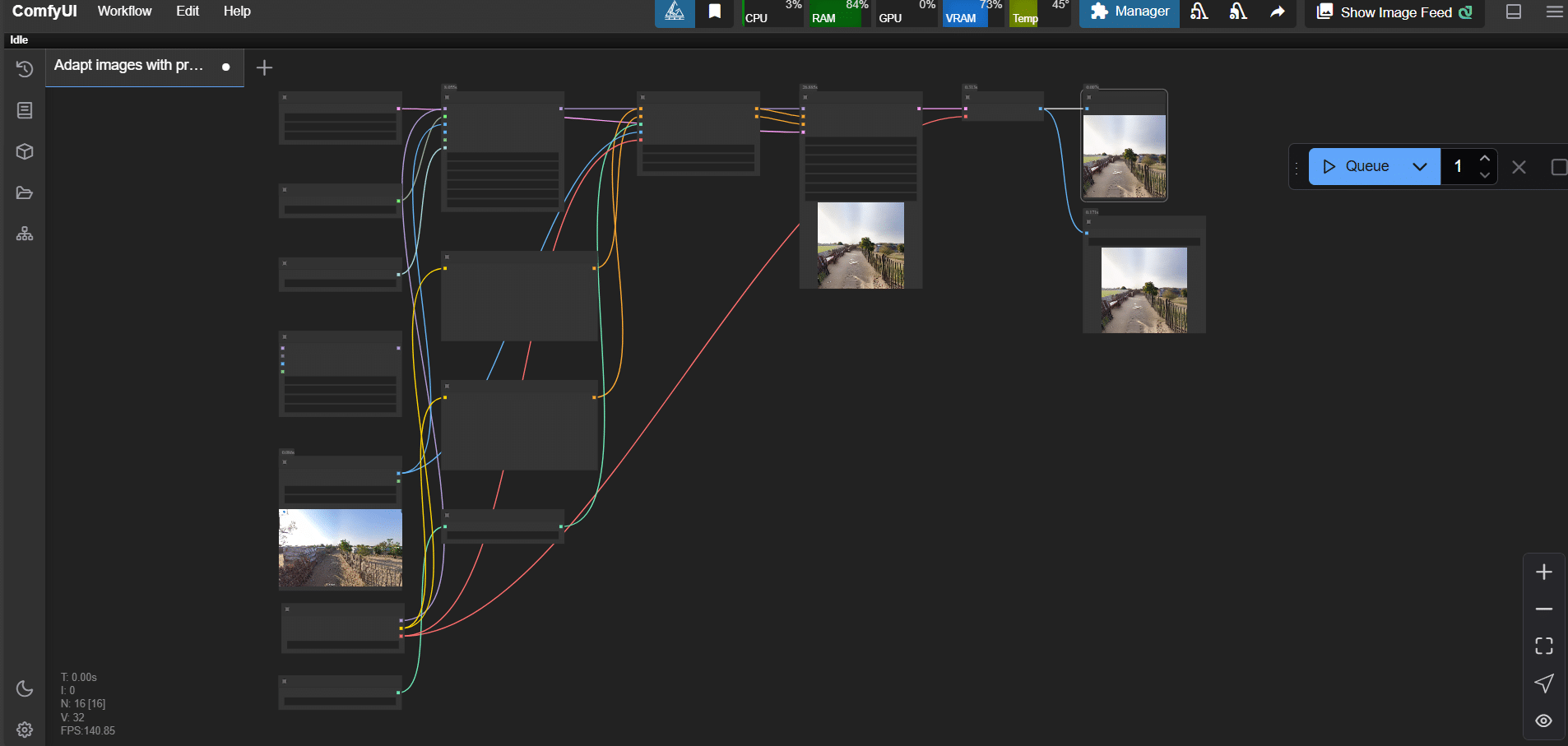

Through Comfyui, we visualize the type of intervention the stake holder wants to give.

Bias/ Difficulties:

We propose to give a scoring atlast to check if the image generated resembles the ideas they feeded during the chat.

Conclusion

The development of this bot enables a participatory design process with the community of Rundu. The photographs and comments they share about how to improve public space serve as bottom-up inputs, allowing residents themselves to define which elements would enhance their experience while commuting to collect water. This creates a valuable database that reflects local preferences, making it possible to understand how public space could be transformed based on gender or age. In this way, we can identify the specific needs of different population groups, such as women, men, children, or the elderly.

Additionally, the photos submitted through the bot contribute to building a visual dataset that offers a better understanding of Rundu’s urban fabric, seen through the eyes of its inhabitants. This is particularly important given the absence of visual data such as Google Street View in Rundu. Normally, we rely on data scraping from platforms like Google Maps to analyze streetscapes, but in this case, those resources are unavailable, making these community-generated images crucial for grasping the current urban context.

Finally, it’s worth highlighting that this activity is also an engaging way for residents to reimagine their public space. The generation and transformation of images using AI has gained immense popularity recently; there’s something inherently captivating about this technology. By leveraging this novelty, we offer users a playful yet meaningful experience, one where they can have fun while actively contributing to the improvement of their city. It’s a chance to imagine a better reality, and enjoy the process of helping to shape it.