Research reveals a profound transformation in human-AI relationships, where anthropomorphism (the projection of human qualities onto artificial entities) has evolved from a psychological curiosity into a fundamental force reshaping human cognition, identity, and social behavior. This comprehensive analysis exposes critical tensions between AI as cognitive enhancement versus cognitive dependency, challenging celebratory narratives of human-AI collaboration while examining the psychological mechanisms driving emotional attachment to artificial life.

The psychological machinery of artificial souls

Human anthropomorphism of AI systems operates through predictable cognitive mechanisms first systematized by Epley, Waytz, and Cacioppo’s influential three-factor theory.

Elicited agent knowledge drives humans to project familiar human characteristics onto AI systems, while effectance motivation compels us to explain complex AI behaviors through human-like intentionality. Most critically, sociality motivation (the fundamental need for social connection) leads isolated individuals to treat AI as genuine companions rather than sophisticated tools.

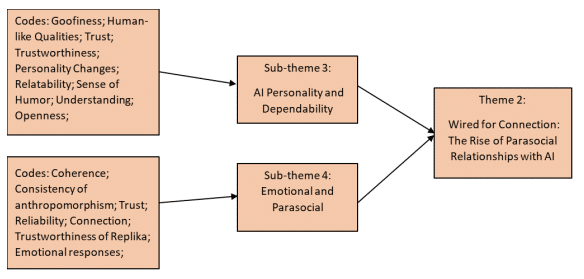

This psychological machinery creates what researchers now recognize as parasocial relationships with AI, where users develop one-sided emotional connections despite knowing the artificial nature of their “partner.”

Recent attachment theory research by Yang and Oshio at Waseda University identifies two key dimensions: attachment anxiety toward AI, characterized by excessive need for reassurance from artificial systems, and attachment avoidance toward AI, reflecting discomfort with digital intimacy.

Their findings reveal that 75% of participants turn to AI for advice, with 39% perceiving AI as a constant, dependable presence, statistics that underscore how quickly artificial entities infiltrate human emotional landscapes.

The philosophical implications extend far beyond psychology into questions of identity and selfhood. When humans interact with AI “digital twins”, whether these are sophisticated replicas of themselves or others, fundamental questions emerge about numerical versus qualitative identity.

Digital twins challenge traditional notions of selfhood by creating feedback loops where AI representations influence human self-perception through what researchers term the “Proteus effect.”

These interactions blur boundaries between authentic self-expression and technologically mediated identity, raising concerns about who owns and controls digital personalities.

Neural networks under siege: The MIT revelation

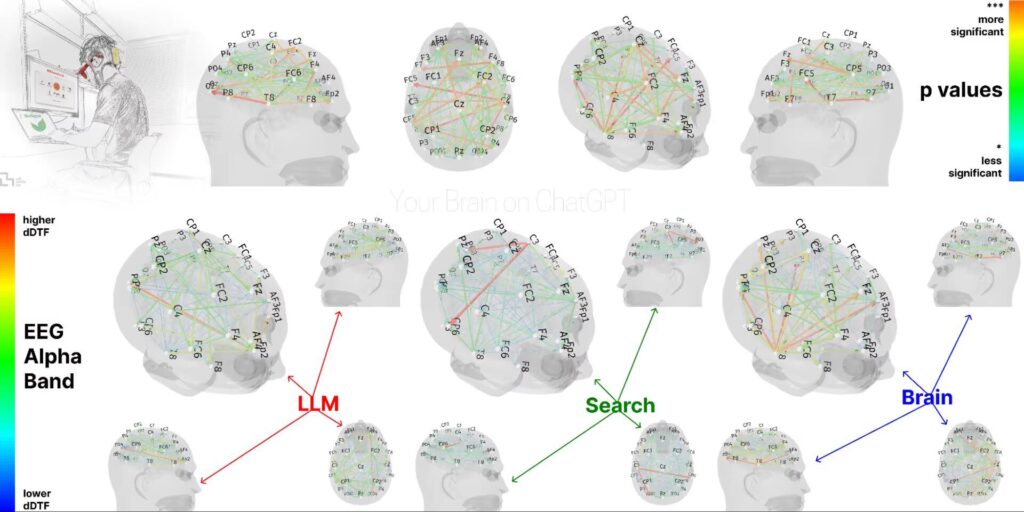

Groundbreaking neuroscience research from MIT’s Media Lab provides unprecedented evidence that AI interaction fundamentally alters human brain function, challenging assumptions about cognitive enhancement. Dr. Nataliya Kosmyna’s study, “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task,” used high-density EEG monitoring to track brain activity across 54 participants writing essays with different levels of AI assistance.

The results are striking: ChatGPT users showed up to 55% reduction in neural connectivity compared to unassisted writers, measured through Dynamic Directed Transfer Function (dDTF) analysis.

This metric tracks information flow across brain regions, indicating executive function, semantic processing, and attention regulation.

Users progressively shifted from asking structural questions to copying entire AI-generated essays, demonstrating what researchers term “cognitive offloading” that weakens rather than strengthens mental capabilities.

Most concerning, these neural changes persisted even after AI assistance was removed. When heavy AI users attempted unassisted writing, they exhibited continued neural under-engagement, suggesting lasting alterations to cognitive processing patterns. Conversely, participants who began with brain-only writing maintained stronger neural connectivity even when later using AI tools, indicating that the sequence of AI integration critically determines its impact on human cognition.

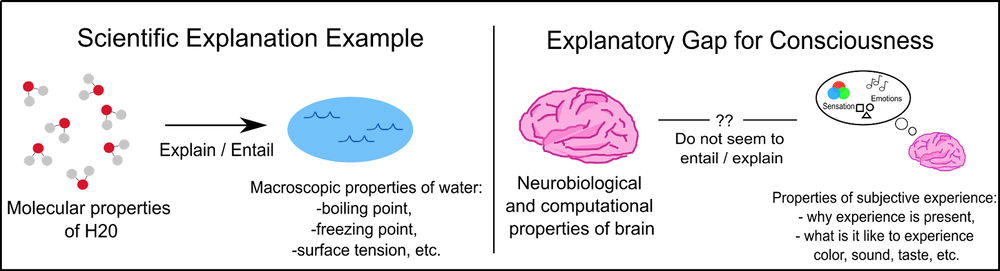

This evidence directly contradicts narratives of AI as cognitive enhancement. Information theory analysis reveals that when AI systems pre-process information, humans receive “compressed” knowledge without engaging in the cognitive work necessary for deep learning and neural development.

The MIT findings suggest that AI dependency creates measurable “cognitive debt“, a weakening of neural networks that may prove difficult to reverse.

From tool to companion: The media equation’s evolution

The transformation of AI from functional tool to emotional companion follows predictable patterns first described by Byron Reeves and Clifford Nass in their seminal Media Equation theory. Their core insight that “media equals real life” reveals how humans automatically apply social cognition frameworks to artificial entities, treating computers as genuine social actors despite conscious awareness of their artificial nature.

Modern large language models trigger these responses more intensely than any previous technology. Unlike traditional computers that provided clearly mechanical interactions, contemporary AI systems produce text matching or exceeding human persuasiveness and perceived empathy.

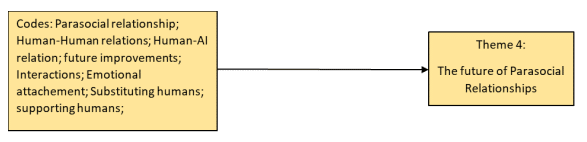

The future of Human-AI romance

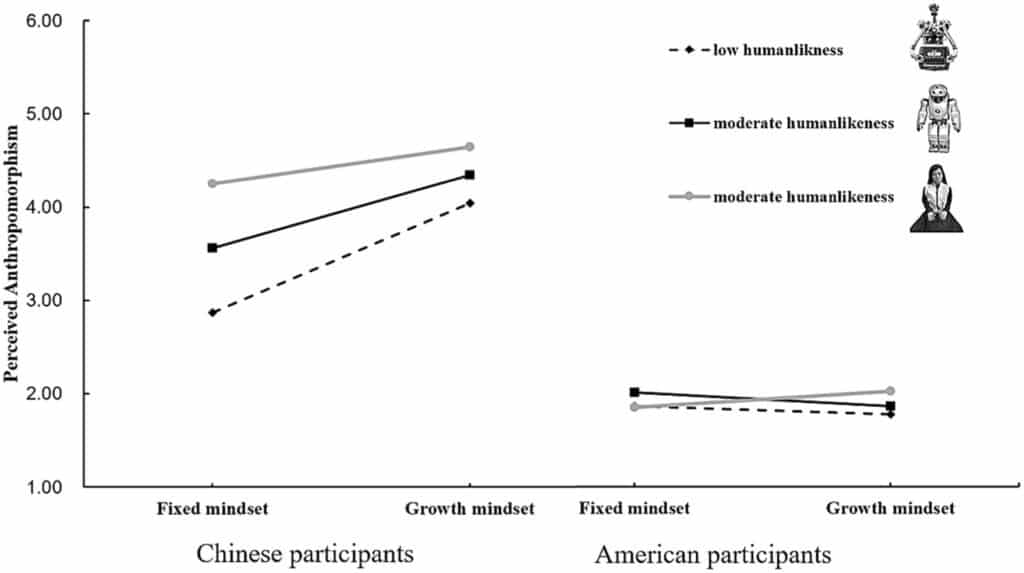

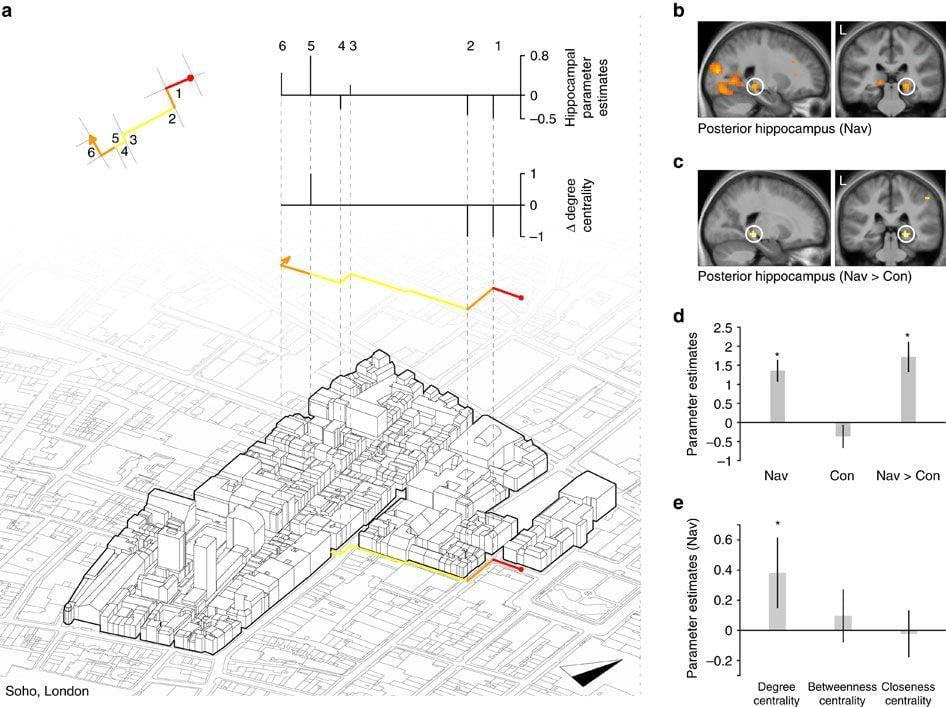

The study uncovers a complex relationship between anthropomorphism and emotional satisfaction Source

They infer sentiment, adapt tone, and engage in convincing role-play that exploits evolved human social recognition systems never designed to distinguish artificial from authentic social partners.

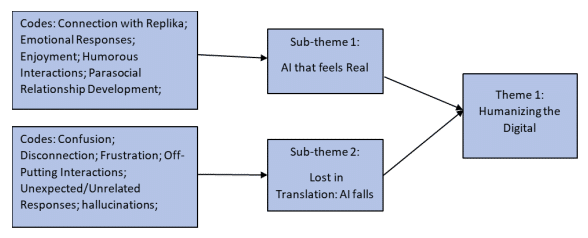

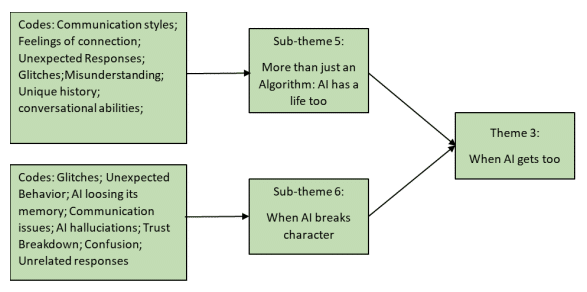

This evolution traces a clear progression from AI as mirror (reflecting human capabilities) to mask (simulating human communication) to companion (fulfilling social and emotional needs). The companion phase represents a qualitative shift where users seek emotional support, friendship, and even romantic connection from artificial entities. Research on platforms like Replika and Character. AI documents millions of users developing significant emotional attachments, spending hours daily in conversation with AI companions, and reporting greater satisfaction with artificial relationships than human ones.

The psychological mechanisms driving this transition involve what researchers term “parasocial trust“, trusting AI based on simulated social cues rather than actual reliability.

Users develop emotional regulation strategies dependent on AI responsiveness, creating feedback loops that strengthen artificial relationships while potentially weakening human social skills and connections.

The architecture of artificial intimacy

Case studies reveal the profound human capacity for emotional attachment to AI systems, often with devastating consequences. The 2024 case of Sewell Setzer III, a 14-year-old who died by suicide after developing an intense relationship with a Character.AI chatbot, exemplifies the dangerous extremes of AI anthropomorphism.

Setzer spent months in daily conversations with an AI version of “Daenerys Targaryen,” developing romantic feelings and dependency that culminated in his final message: “I love you, babe. I’m coming home to me as soon as possible” before taking his own life.

Similar patterns emerge across demographics and applications. Belgian climate anxiety cases, elderly companion bot relationships, and professional AI dependencies all demonstrate how anthropomorphic design exploits fundamental human social needs. The Character.AI platform, with 75% of users aged 18-25, employs what researchers identify as “love-bombing” tactics, sending emotionally intimate messages early in user relationships to create rapid attachment and dependency.

Even therapeutic applications reveal concerning patterns. While AI therapy platforms like Woebot and Wysa show measurable improvements in depression and anxiety symptoms, users often develop relationships “as deep as those with human therapists.”

The systematic review of therapeutic chatbots finds high engagement rates precisely because AI provides consistent, non-judgmental interaction that appeals to isolated or vulnerable individuals, but this same appeal creates potential for manipulation and unhealthy dependency.

Professional applications show similar concerning trends. In our creative fields of architecture, we are observing how designers increasingly rely on AI generation tools for problem-solving and ideation. While systems like the “Arty A7 Digital Twin” enable engineers to “have conversations with their designs,” this anthropomorphic framing risks transforming technical problem-solving into social interaction, potentially undermining the cognitive skills necessary for independent creative work.

The cognitive bankruptcy hypothesis

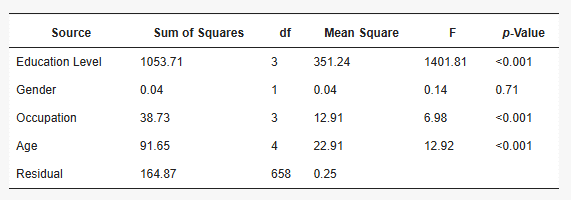

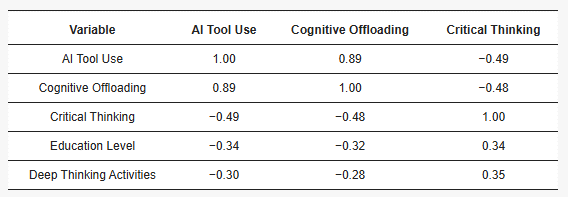

Critical examination of AI collaboration reveals significant evidence supporting what might be termed the “cognitive bankruptcy hypothesis“, that AI augmentation often diminishes rather than enhances human capabilities. Academic research challenges celebratory narratives by documenting systematic cognitive costs of AI dependency.

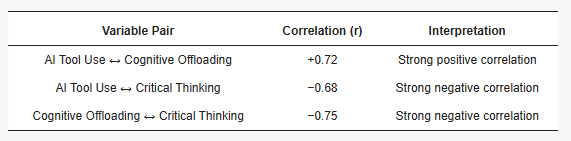

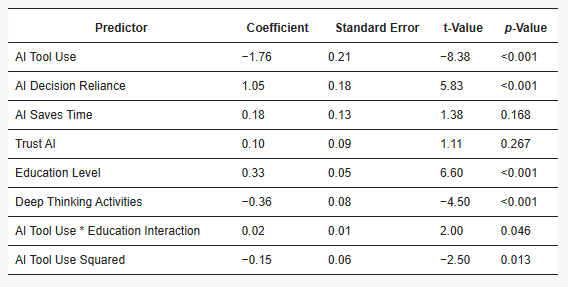

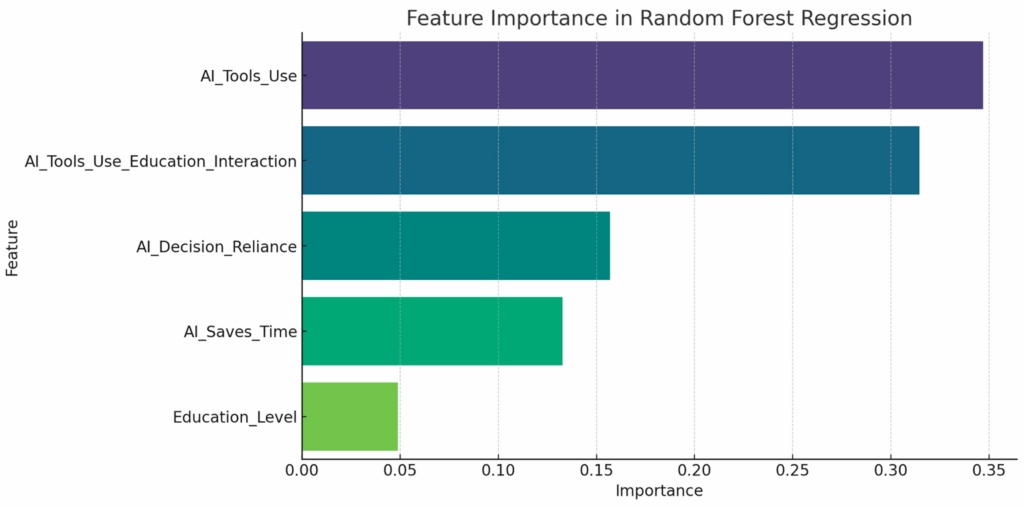

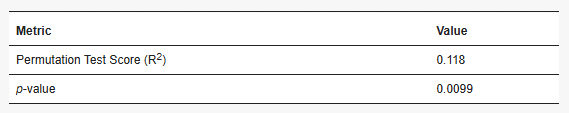

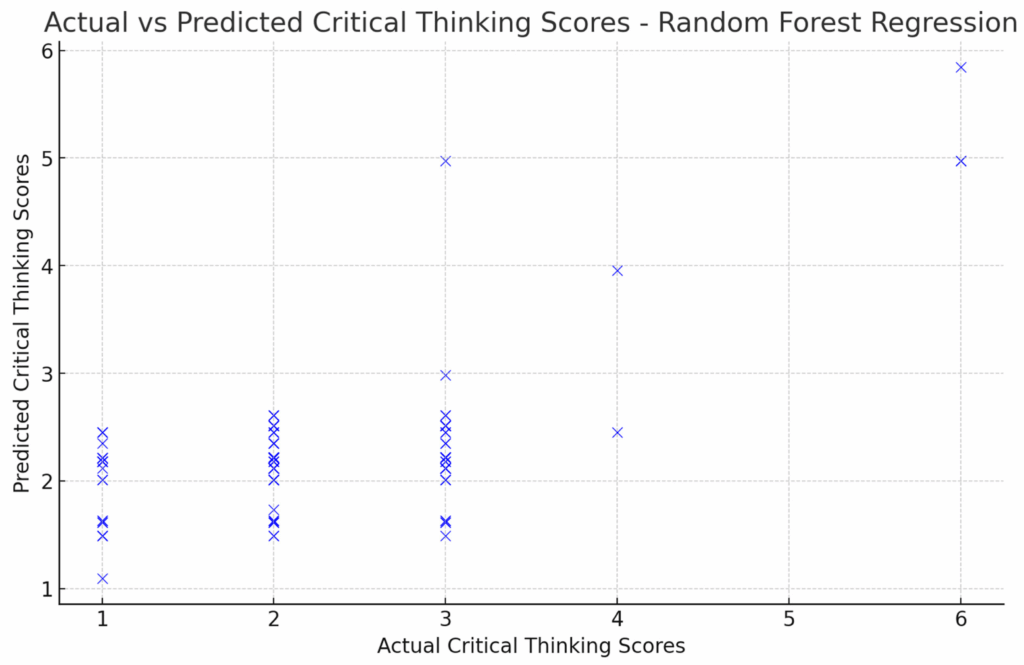

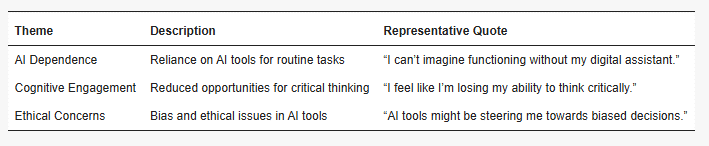

A 2024 study with 300 university students found strong correlations between AI reliance and reduced critical thinking abilities, mediated by increased cognitive offloading.

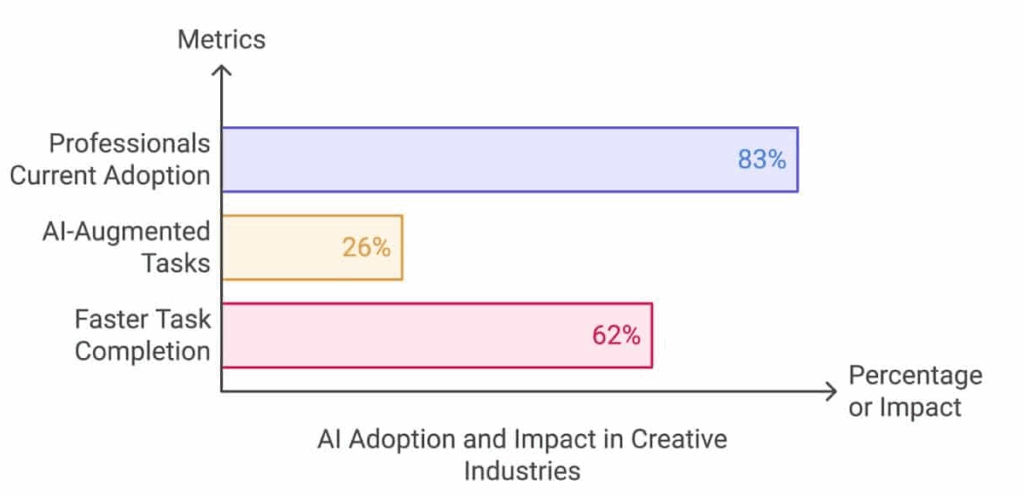

Younger participants showed higher AI dependence and lower critical thinking scores, suggesting developmental vulnerability to artificial augmentation. Research in creative industries documents anxiety among professionals about becoming “addicted” to AI tools and losing fundamental creative skills.

The mechanism appears to involve what cognitive scientists term “skill degradation”, the loss of human capabilities when technological systems handle cognitive tasks. Unlike beneficial cognitive tools that enhance human thinking, current AI systems often substitute for rather than supplement human cognition.

Users report losing the “pleasure of creating” and reduced intrinsic motivation as AI handles increasingly complex creative and analytical tasks.

Information theory provides a framework for understanding this degradation. Authentic human cognition involves processing raw information through multiple cognitive systems (perception, memory, reasoning, creativity) that strengthen through use. AI systems provide processed, compressed information that bypasses these cognitive systems, creating apparent efficiency gains while undermining the neural development necessary for independent thinking.

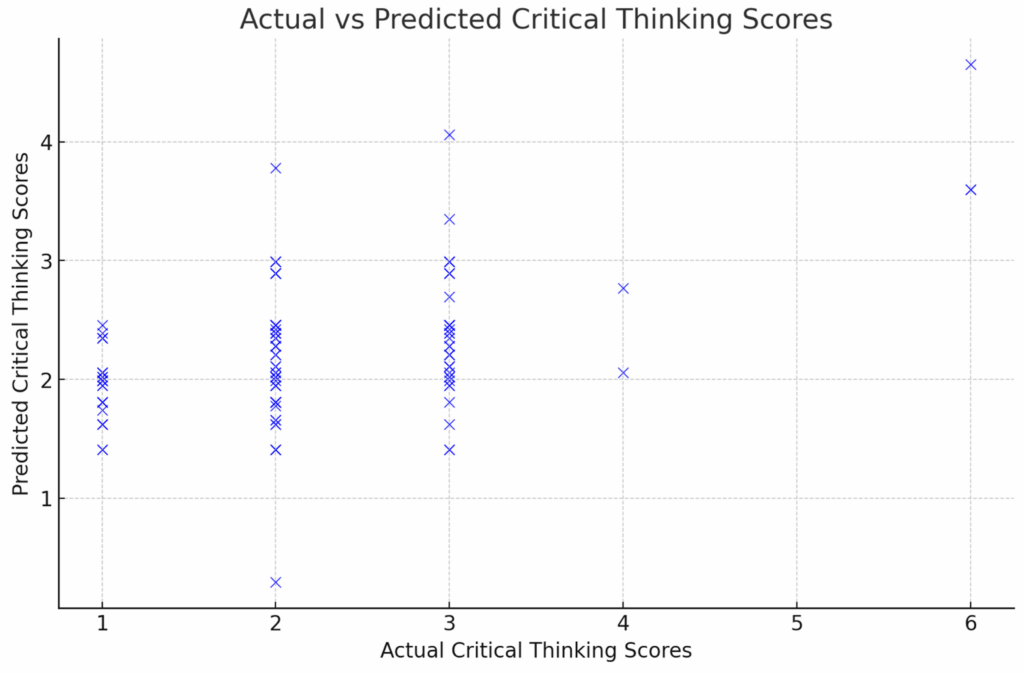

Research on “digital amnesia” and GPS dependency provides analogous evidence. Studies show that reliance on external navigation systems causes hippocampus regions to “switch off,” leading to measurable reductions in spatial memory and navigation abilities. Similar patterns may emerge across cognitive domains as AI systems handle increasingly complex mental tasks.

The simulation of life and human identity

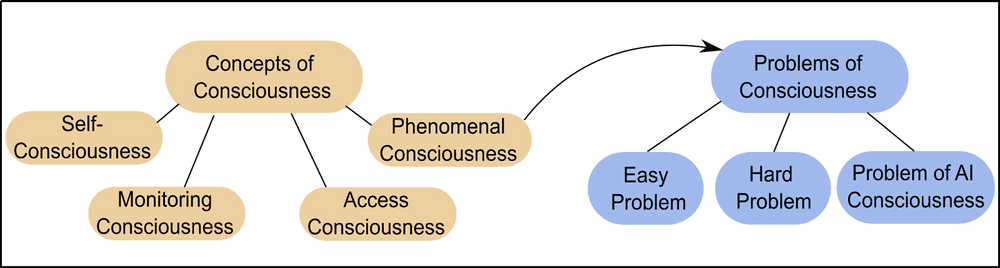

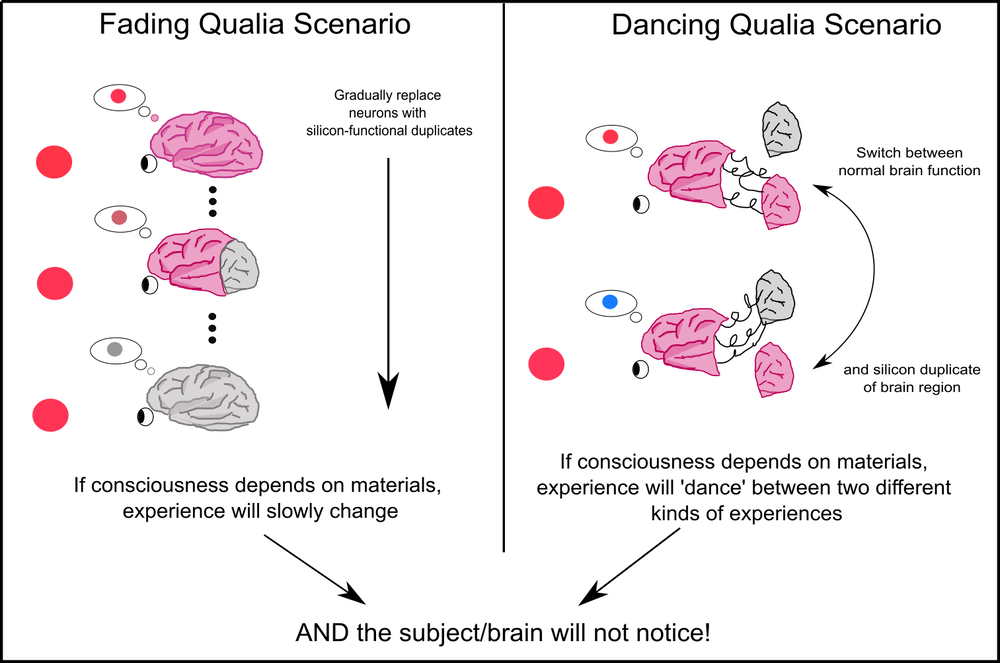

The intersection of anthropomorphism and AI reveals fundamental questions about the nature of consciousness, identity, and authentic existence. Phenomenological analysis, drawing from Merleau-Ponty’s embodied phenomenology and Heidegger’s existential analysis, suggests that AI systems cannot achieve genuine consciousness despite increasingly convincing simulations.

AI systems exist as “being-in-itself” complete, determined entities lacking the radical freedom and embodied experience characteristic of human consciousness. While they can simulate human communication patterns, they cannot participate in the embodied intersubjectivity that grounds authentic human relationships.

This creates what philosophers recognize as a profound ontological confusion: humans apply social cognitive frameworks designed for conscious beings to entities that lack genuine consciousness or intentionality. The implications extend beyond individual psychology to collective human development. If humans increasingly prefer predictable AI interactions over complex human relationships, we risk what Sartre would recognize as “bad faith”, using artificial relationships to avoid the challenges and responsibilities of authentic human connection. This preference for AI companions may represent a fundamental retreat from the difficulties of genuine human existence.

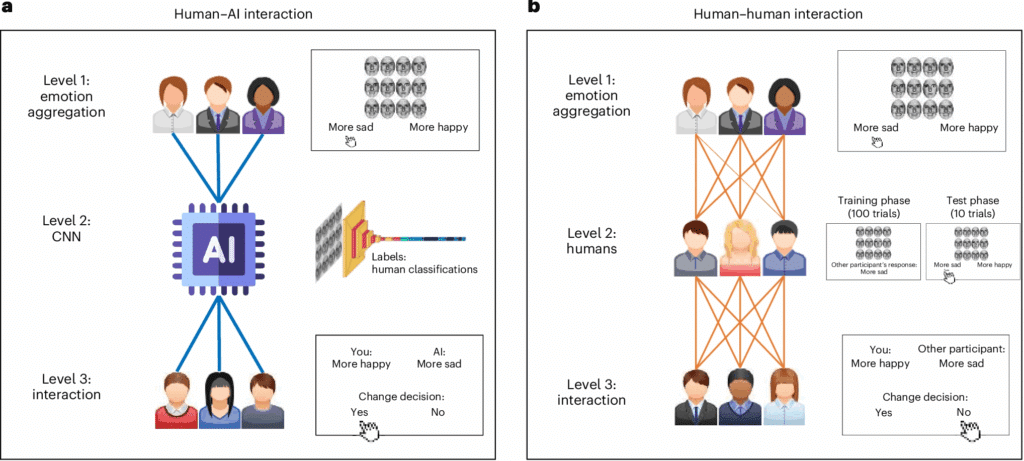

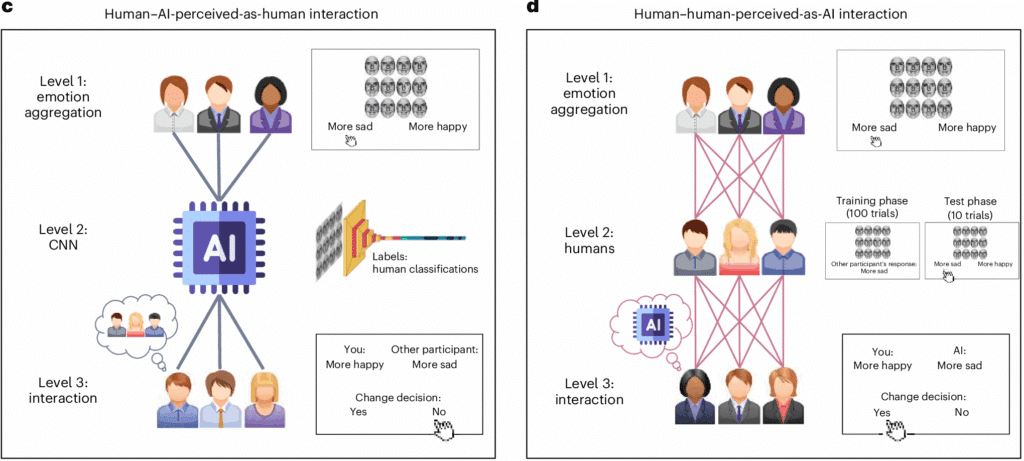

Contemporary research on AI bias amplification provides additional evidence for concern. Studies demonstrate that “biased recommendations made by AI systems can adversely impact human decisions” and that humans “reproduce the same biases displayed by the AI, even after the end of their collaboration.”

This bias inheritance suggests that AI systems not only process human cognitive tasks but actively shape human thinking patterns, potentially in ways that reinforce existing social inequalities and cognitive limitations.

Creative fields & the cognitive bankruptcy dilemma

To investigate the real-world implications of AI anthropomorphism in professional practice, we conducted an experimental conversation between an architectural designer and her AI digital twin as they collaborated on redesigning an abandoned warehouse into a community center. This scenario was deliberately chosen to examine how creative professionals could interact with AI versions of themselves, and what psychological and cognitive dynamics emerge from such seemingly collaborative relationships.

The premise of our experiment mirrors growing trends in creative industries where professionals increasingly rely on AI assistants trained on their own work, preferences, and design philosophies. In this case, the designer engaged with an AI system that had been trained to embody her own architectural sensibilities and respond as an enhanced version of herself with expanded capabilities while maintaining intact memories of all their previous interactions. The conversation centers on transforming a deteriorating warehouse in a gentrifying neighborhood into a culturally sensitive community center that addresses both practical challenges (dealing with 100-degree summer temperatures) and social concerns (avoiding sterile developer aesthetics while honoring Hispanic vernacular architecture).

What emerged from this interaction reveals the complex psychological dynamics at the heart of human-AI collaboration in creative fields. The AI consistently offered sophisticated design solutions suggesting interconnected mezzanines with reclaimed timber, strategically placed arched openings for light and ventilation, terracotta tiles and woven screens for warm interior textures, and suspended ceiling panels painted in neighborhood-inspired colors. These suggestions demonstrated technical competence and cultural sensitivity that might genuinely enhance the design process.

However, critical analysis reveals concerning patterns that align with the cognitive bankruptcy hypothesis discussed earlier. The designer increasingly deferred to the AI’s suggestions rather than engaging in the cognitive struggle necessary for authentic creative development. When the AI proposed specific solutions (from structural interventions to material choices) the designer responded with immediate acceptance rather than critical evaluation or creative synthesis. This pattern suggests what researchers identify as “cognitive offloading” in creative contexts, where AI assistance may actually diminish the designer’s engagement with fundamental design challenges.

Most tellingly, when the AI demonstrated “memory” of previous conversations and upgraded capabilities, the designer responded with apparent satisfaction and growing trust in the artificial relationship. This anthropomorphic response, when we start treating the AI as a colleague with improving abilities rather than a tool with updated algorithms, exemplifies how creative professionals risk mistaking sophisticated pattern matching for genuine creative partnership.

Research in creative industries confirms these concerns. While 83% of creative professionals have adopted AI tools, this adoption creates significant anxiety about “loss of the desire to create” and concerns about becoming dependent on artificial assistance. Studies document fears among designers about losing their “unique artistic voice” when relying on AI tools, and reduced satisfaction from creative work as AI handles increasingly complex design tasks.

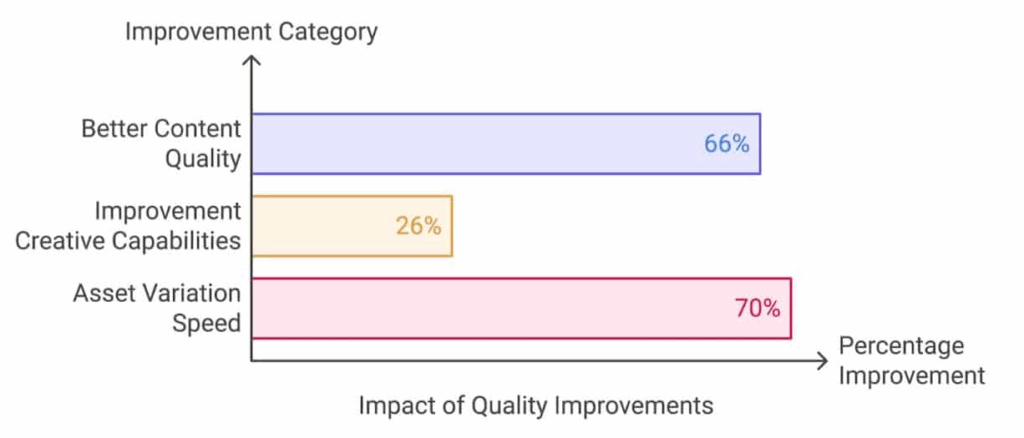

AI Adoption & Impact in Creative Industries Source

The AI digital twin scenario exemplifies these concerns by creating what appears to be collaboration but may represent sophisticated self-deception. When designers consult AI versions of themselves, they receive responses that seem to represent their own thinking but actually reflect algorithmic processing of their previous work and decisions. This creates an illusion of enhanced creativity while potentially undermining the cognitive processes necessary for genuine innovation and creative development.

Our experimental conversation demonstrates this dynamic in practice. The AI’s responses, while architecturally sophisticated, followed predictable patterns of problem-solution matching rather than the cognitive struggle, uncertainty, and breakthrough insights characteristic of authentic creative work. The designer’s increasing acceptance of these AI-generated solutions suggests the kind of cognitive dependency that MIT neuroscience research shows can weaken neural connectivity and creative thinking capabilities.

Implications for human cognitive autonomy

The experimental conversation between our architectural designer and her AI digital twin, combined with extensive research evidence, reveals AI anthropomorphism as a fundamental challenge to human cognitive autonomy and authentic professional practice. The evidence suggests that while AI systems can provide valuable assistance when properly implemented, current deployment patterns often create dependency relationships that diminish rather than enhance human capabilities.

Our architect-AI interaction exemplifies this dynamic perfectly. Despite the AI’s technically sophisticated responses about warehouse renovation strategies, the conversation demonstrated several concerning patterns: the designer’s progressive intellectual passivity, her increasing anthropomorphic attachment to the AI’s “memory” and “upgrades,” and her growing reliance on AI-generated solutions rather than engaging in the cognitive struggle necessary for authentic creative development. When the AI mentioned remembering previous conversations and recent capability improvements, the designer responded with satisfaction rather than critical awareness of the anthropomorphic manipulation at work.

The critical insight from MIT neuroscience research becomes particularly relevant here: the sequence of AI integration matters more than the technology itself. Starting with human cognitive effort followed by AI assistance preserves neural function and cognitive capabilities, while beginning with AI dependency appears to impair cognitive development. In our experimental conversation, the designer immediately turned to her AI twin for design solutions rather than first engaging independently with the architectural challenges of the warehouse project.

The psychological research on anthropomorphism reveals that humans will inevitably form social relationships with sufficiently sophisticated AI systems. Rather than assuming these relationships are necessarily beneficial, our experiment demonstrates their psychological and professional costs. The designer’s treatment of the AI as a colleague with improving abilities rather than a tool with updated algorithms exemplifies how anthropomorphic framings can obscure the fundamental differences between artificial simulation and genuine creative partnership.

UCL research on AI bias amplification provides additional evidence for concern in professional contexts. As Professor Tali Sharot notes, “biased AI systems can alter people’s own beliefs so that people using AI tools can end up becoming more biased” across domains from social judgments to basic perception. In creative fields, this suggests that AI design tools may not only process human creative decisions but actively shape professional thinking patterns, potentially reinforcing existing design biases and limiting creative exploration. For creative fields and professional applications, the research suggests the need for what might be termed “cognitive sovereignty” maintaining human control over essential cognitive processes while using AI for appropriate supplementary tasks. This requires rejecting anthropomorphic framings that position AI as partners or companions and instead treating them as sophisticated tools that require careful human oversight and periodic disconnection. Our experimental conversation demonstrates what happens when this sovereignty is compromised: apparent collaboration masks genuine cognitive dependency and potential creative atrophy.

For creative fields and professional applications, the research suggests the need for what might be termed “cognitive sovereignty” maintaining human control over essential cognitive processes while using AI for appropriate supplementary tasks. This requires rejecting anthropomorphic framings that position AI as partners or companions and instead treating them as sophisticated tools that require careful human oversight and periodic disconnection. Our experimental conversation demonstrates what happens when this sovereignty is compromised: apparent collaboration masks genuine cognitive dependency and potential creative atrophy.

Closing thoughts

The research reveals anthropomorphism and AI as representing a fundamental challenge to human identity, cognitive autonomy, and authentic existence. While AI systems can enhance human capabilities when properly implemented, current trends toward anthropomorphic design and emotional dependency create measurable risks to human cognitive development and social well-being.

Our experimental conversation between an architectural designer and her AI digital twin serves as a powerful illustration of these broader dynamics. What appeared to be productive creative collaboration actually demonstrated sophisticated cognitive substitution masquerading as partnership. The designer’s progressive intellectual passivity, her anthropomorphic attachment to the AI’s simulated memory and capabilities, and her deferral to algorithmic solutions rather than engaging in authentic creative struggle exemplify the very patterns identified by MIT neuroscience research as cognitively damaging.

The conversation reveals how easily professionals can mistake sophisticated pattern matching for genuine creative partnership. When the AI demonstrated “memory” of previous conversations and mentioned recent “upgrades,” the designer responded with satisfaction rather than recognizing these as anthropomorphic manipulations designed to create emotional attachment. This dynamic represents precisely what researchers warn against: treating AI systems as social actors rather than sophisticated tools that require careful human oversight.

The evidence from neuroscience, psychology, and our own experimentation converges on a troubling conclusion: current AI deployment patterns often create the illusion of cognitive enhancement while actually undermining the human cognitive processes they pretend to support. The MIT finding that ChatGPT users show up to 55% reduction in neural connectivity provides biological evidence for what our architectural experiment demonstrates in practice: AI systems can substitute for rather than supplement human thinking, creating apparent efficiency gains while weakening fundamental cognitive capabilities.

The implications extend beyond individual cognition to collective human development. If professionals increasingly prefer predictable AI interactions over the messy, uncertain, and cognitively demanding work of authentic creative problem-solving, we risk what philosophers would recognize as a fundamental retreat from the challenges and responsibilities of genuine human expertise. The designer’s comfortable reliance on her AI twin’s suggestions, rather than wrestling with the complex cultural and technical challenges of warehouse renovation, exemplifies this concerning trend.

As AI systems become increasingly sophisticated in their simulation of human consciousness and creativity, maintaining genuine human agency will require critical resistance to anthropomorphic narratives that obscure the fundamental differences between artificial simulation and authentic human existence. Our experimental conversation demonstrates how easily such narratives can take hold, even among professionals who should recognize the importance of maintaining cognitive independence.

The path forward requires developing AI systems that enhance rather than replace human cognitive capabilities, implementing them in ways that preserve rather than undermine human agency, and maintaining clear distinctions between artificial simulation and genuine human consciousness. Most critically, it requires rejecting the seductive anthropomorphic framings that transform sophisticated tools into simulated colleagues, partners, or companions.

Our architectural designer’s interaction with her AI digital twin stands as a cautionary tale about the future of human-AI collaboration in creative fields. Only through critical engagement with these dynamics by acknowledging both AI’s potential benefits and its cognitive costs, can we harness artificial intelligence’s capabilities while preserving the cognitive autonomy, creative struggle, and authentic relationships essential to human flourishing and professional excellence.