Guest Lecture at IAAC (14 October 2025) – Exploring how La Máquina merges design, robotics, and the human element.

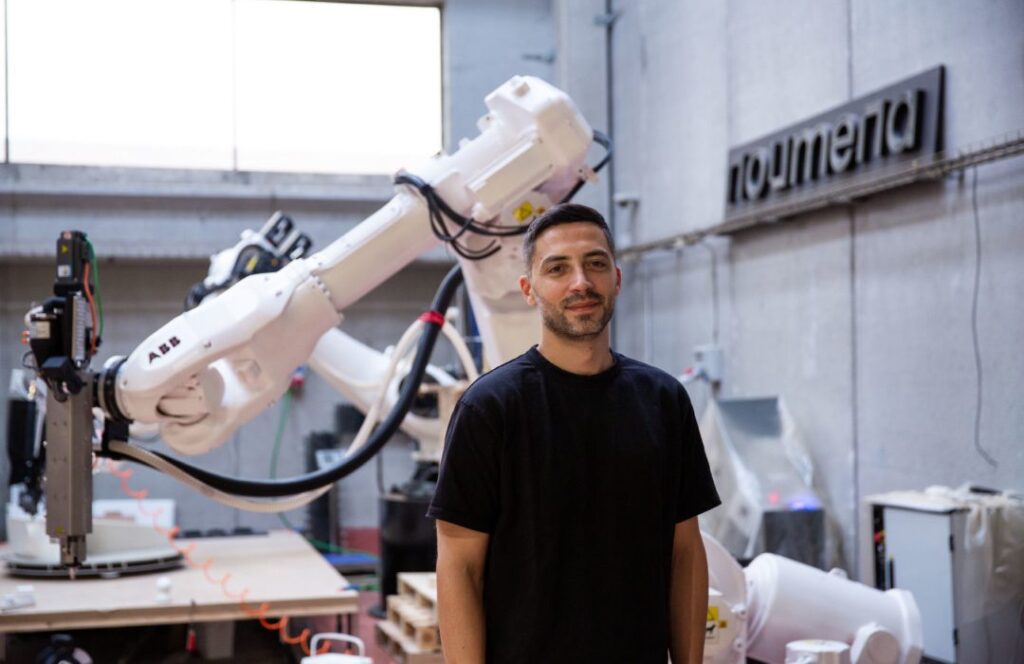

During one of our sessions at IAAC, we had the opportunity to meet Aldo Sollazzo, co-founder of La Máquina, Noumena, and Pure.Tech, as well as a former IAAC faculty member in the field of robotic fabrication.

Invited through the coordination of the MRAC program, Aldo visited IAAC to reconnect with the school and share his professional journey, reflecting on the evolving relationship between design, robotics, and material innovation.

As MRAC students, we had the chance to personally meet him, learn from his experiences across his different companies, and ask questions about how he balances creative vision with technical precision in the context of advanced construction.

“Presentedby Retail Space” Robotic manufacturing project by La Máquina. Image courtesy of lamaquina.io

Q1 — When you bring together such different minds – architects, coders, engineers, and artists – how do you make sure the project doesn’t lose its soul in all the technical precision?

Aldo Sollazzo:

The soul comes when clients approach us wanting to do something new. They are always searching for innovation, and that requires humility from our side. You need to interpret this need – to tune with the client, to understand what they want from you, why they came to you, and what challenge they are trying to overcome. Otherwise, you can’t bring real value to the project.

There are projects that are banal, and others that really push boundaries. With time, we also started saying no to things that we are not interested in. It’s difficult to say no because you know you are closing an opportunity, especially when you’re still small. But if something is taking your time without building your future, it’s probably not worth your effort.

Q2 — Within La Máquina, each project seems to demand different types of expertise. How do you decide who leads? For instance, when collaborating with External Reference, how do you balance the system and the design sides?

Aldo Sollazzo:

When we started, I had to make a strategic decision. At that time, I was designing, teaching computational design at IAAC, and many of the designers at Carmel’s office (External Reference) were my former students – people I admire a lot.

But I had to decide whether I wanted to design, fabricate, do the marketing, and lead three companies at once, or to take a step back. We decided to turn 3D printing into a new engineering protocol for design – not only as a fabrication tool but as a process that connects design and manufacturing.

By doing that, we opened the workflow to others. If I design only for myself, everything depends on me. But if I convert this into a service, it becomes open to other people – architects, designers, engineers. This approach also shaped our collaborations with External Reference. We’re like two halves of the same system: they focus on the expressive and spatial side of design, while we focus on the systemic and material logic. When those two connect, it becomes something powerful.

Q3 — Out of all the projects you’ve worked on, which one challenged you the most?

Aldo Sollazzo:

Two months ago, I would have said the project we finished then was my dream one. But recently, I received a call for another project that I’ve always wanted to do. So it’s constantly evolving — every time something new arrives, it becomes part of that dream. Each project brings its own challenges, and that’s what keeps it interesting.

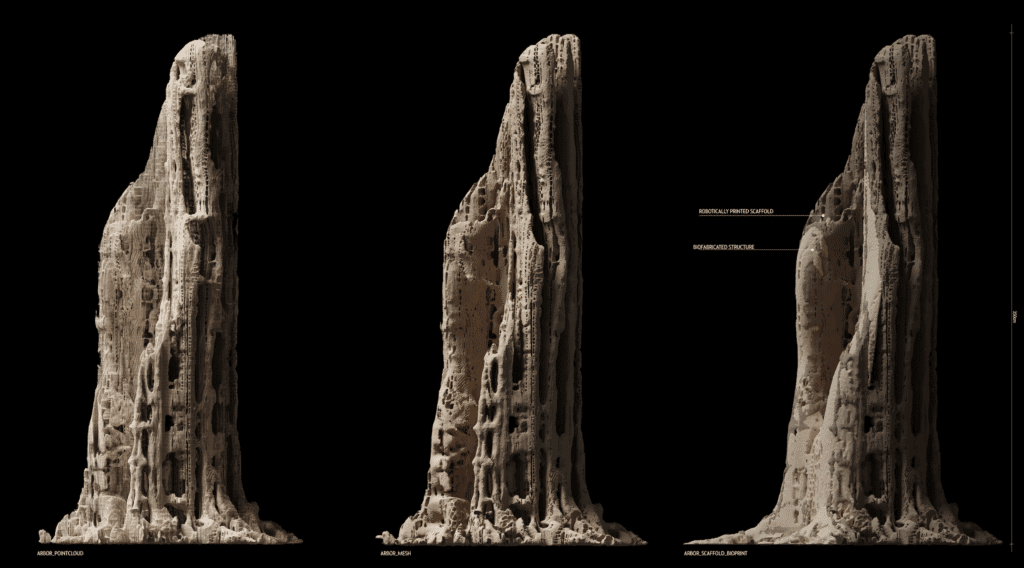

(Editor’s note: Aldo was likely referring to “Arbor,” a biocomposite installation created with Maria Kupsova and exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale.)

“Arbor,” a biocomposite installation created by Aldo Sollazzo and Maria Kuptsova. Image courtesy of mariakuptsova.com

Q4 — What led you to focus on climate change, sustainability, and projects like RESPIRA? Was there a moment when you realized you wanted your work to have a direct environmental impact?

Aldo Sollazzo:

When I was a student, I wanted to work on things that had meaning, and I felt the need to contribute somehow. I saw design not just as a tool for creating, but also for leaving a trace — a way to make an impact. Over time, I started to feel that this kind of contribution is part of what we’re meant to do— not as a strict obligation, but as a way to engage with the world responsibly.

Q5 — How do you start exploring new materials? What tests do you perform?

Aldo Sollazzo:

testing things informally. But when it gets serious, we need to certify. That means checking resistance, porosity, and other properties in a lab. ISO certification is key, because it’s how companies trust the material. It’s a long process — we’ve been working on it for years, especially with PURE.TECH. You can’t just invent something and expect it to be used. You have to prove it works.

Throughout the lecture, Aldo presented a unified vision of how digital fabrication, robotics, and material science can merge into a coherent design ecosystem. He described his work not as a purely technological pursuit but as a human process that requires empathy and interpretation. Beyond precision, he argued, the architect must understand why a project exists, what the client truly seeks, and how technology can express that intention meaningfully.

He traced his professional evolution, from teaching computational design at IAAC to leading multidisciplinary teams at Noumena and La Máquina. This path led him to rethink authorship and shift from being the single designer managing everything to creating a system-based approach, where collaboration and shared protocols drive innovation.

By turning 3D printing into an engineering protocol, Aldo and his teams redefined how design intelligence transfers from concept to production. Innovation, he said, is not about doing everything yourself but about building frameworks that enable others to contribute creatively within the same system.

Aldo also spoke about ethics in innovation, the importance of saying no to projects that don’t align with long-term vision. Choosing future-oriented work over immediate profit, he noted, is essential for maintaining both creative and intellectual integrity.

He illustrated these principles through recent projects. At La Máquina, large-scale robotic manufacturing has been applied to retail environments such as the Presentedby Retail Space, while Pure.Tech develops bio-based materials that absorb CO₂ and NOx. These are not isolated experiments but connected steps toward a more sustainable and data-driven design culture, where environmental performance becomes part of architectural language.

Concluding his talk, Aldo reflected on the evolving nature of ambition: each project feels like a dream until a new one arrives. That constant evolution, he said, keeps the process alive.

His lecture reminded us that contemporary architecture is not a choice between art and technology but a dialogue between them, a space where soul and system coexist, and innovation serves both creativity and responsibility.

Q6: Is it possible to use machine learning to improve manufacturing processes?

ANSWER:

Aldo stated that such a method is currently being studied and discussed in architecture, design, and manufacturing conferences. This approach would allow machines to perform self-corrections during the production process and to predict whether a given geometry can be successfully completed.

Q7: With the material you developed, is it already possible to sell carbon credits?

ANSWER:

Aldo replied that he intends to sell carbon credits and is in the process of obtaining the necessary legal authorization. However, he warned about greenwashing, which presents itself as a sustainable practice but is often exploited by companies to produce and consume more, thereby undermining the genuine purpose of trading such credits.

Credits

Interview by: Onur Berk Doğrultucu

Location: IAAC, Barcelona

Program: MRAC 25/26 – Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia

Photo: Image courtesy of Habilis.cat | Image courtesy of mariakuptsova.com