The lecture examined the evolution of digital fabrication, open-source hardware, and distributed manufacturing, emphasizing the relationship between technology, culture, and society. Fab Labs were presented as environments that democratize access to production tools, bridging the gap between industrial processes and individual creativity.

The discussion traced the historical transformation from centralized industrial systems to decentralized innovation. Drawing from the early development of personal computing and the maker movement, it highlighted how grassroots experimentation has often been a driving force behind major technological progress. Projects such as RepRap and MakerBot were introduced as milestones that reclaimed fabrication from large industries and returned it to individual and community contexts.

Technology was framed as a cultural phenomenon rather than an external or neutral tool. Machines, software, and digital infrastructures are understood as cultural constructs that reflect collective intelligence and social values. Within the Fab Lab model, this manifests as open documentation, peer-to-peer learning, and the integration of design, science, and craft practices.

A significant theme focused on the connection between information and materiality — illustrating how every digital action is rooted in physical processes, energy use, and material transformation. This interdependence challenges the conventional separation of the digital and the physical, encouraging more responsible and holistic design thinking.

The lecture further explored the Fab Lab Network as a global structure based on replication rather than expansion. Growth occurs through the sharing of knowledge and principles rather than through centralization, enabling each local lab to adapt its practices to specific cultural and environmental contexts while maintaining a shared infrastructure.

Attention was also given to the educational and ethical dimensions of digital fabrication. Fab Labs function as civic and pedagogical spaces where learning by doing fosters awareness of sustainability, responsibility, and collaboration. The approach connects digital fabrication with ecological awareness, encouraging the use of renewable and bio-based materials, distributed energy systems, and circular design strategies.

Ultimately, the lecture positioned digital fabrication not merely as a technical practice but as a cultural and environmental framework for reimagining production, creativity, and community in the 21st century.

How do self-made products fabricated by individuals in Fab Labs comply with certification requirements when intended for sale or use?

In Fab Labs, this issue is often solved in a practical way. Instead of selling finished, certified products, many makers choose to share or sell kits and parts that others can assemble themselves. This approach keeps the process open and educational while avoiding some of the strict regulations attached to commercial manufacturing. What’s really being shared is the knowledge and design, not just the object itself. Once a project grows and there’s real demand, collaboration with certified workshops or small producers usually follows. That way, the product can meet safety or quality standards without losing the openness and creativity.

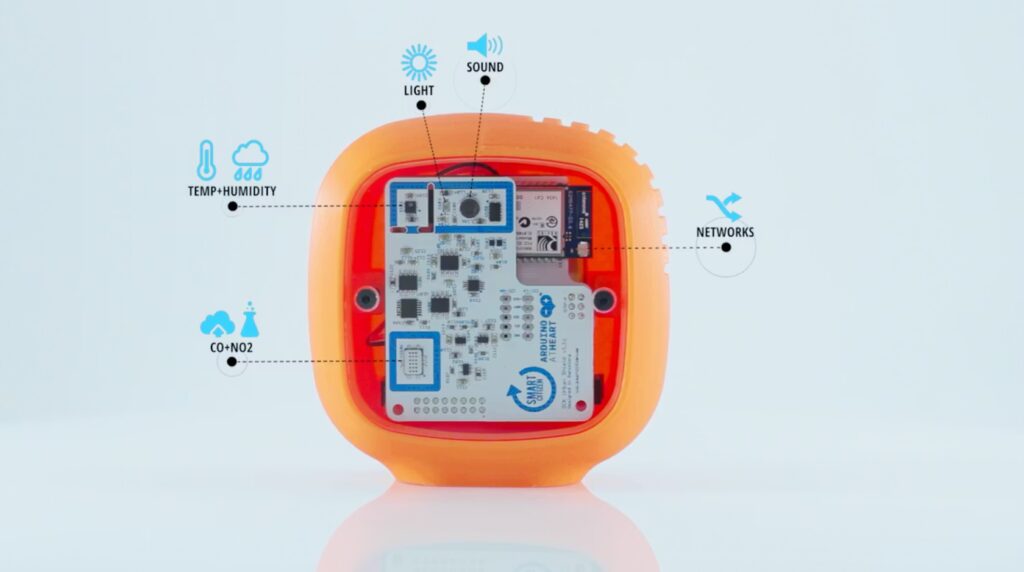

Regarding the “Smart Citizen” devices, how long can the devices stay active collecting data?

Smart Citizen devices are used in many different ways — sometimes for short-term experiments, like measuring air pollution during a building renovation, and sometimes for long-term monitoring that lasts years. At any given time, around 300–400 devices are actively publishing data on the platform, but many others operate locally or through other networks. Each device can store about a month of data internally, and with an SD card, it can record for years. The project has recently started organizing data into “experiments” — groups of devices working toward a specific purpose — to give a clearer view of how sensors are used in context, beyond just showing dots on a map.

One of the big questions around the Fab Lab model is about scale — what are its real limits when it comes to producing for a city, both in terms of quantity, quality, and even the physical size of architectural elements?

One of the main challenges has been understanding the limits of scale in what a Fab Lab can deliver for a city. Rather than being a place of mass production, a Fab Lab acts as a coordinator — a space where knowledge, technologies, and local actors connect to make distributed production possible. This vision expands beyond individual labs toward a “full stack” model: integrating micro-factories, repair centers, educational spaces, and local policies. The Fab City project explores how cities can produce locally while sharing knowledge globally, redefining boundaries not by geography but by bioregional resources and supply chains. Ultimately, Fab Labs can even support one another, creating tools and machines for the next generation of labs.

You mentioned the connection with Industry 4.0. How do Fab Labs actually interact with that kind of industrial network? Do they collaborate physically, for example by developing new tools together, or is it more about online coordination and knowledge sharing?

What’s interesting about Industry 4.0 is its potential to rethink urban production. Rather than imagining production in traditional spaces, fully automated systems like 3D printers could operate in small urban areas, producing on demand. The main challenge, however, is not production capacity but where the knowledge resides. Fab Labs benefit from openness, allowing people to understand and fix machines locally. In contrast, imported automated systems rely on external expertise, creating vulnerability if technicians are unavailable. True local production requires building local know-how, ensuring resilience and long-term capacity rather than simply importing machines or relying on distant expertise.

If you imagine Fab Labs in the future, what do you think they will look like — more automated, more biological, or more connected?

In the future, Fab Labs may change, but their mission won’t disappear. While personal fabrication tools are becoming more accessible, Fab Labs remain essential as spaces for learning, collaboration, and empowerment. Guillem argues that even if everyone owns machines, we still need places that teach us how to understand, repair, and hack them. Beyond technology, Fab Labs provide safe and inclusive spaces—especially for those who don’t have such environments at home. Their future lies not in replicating an old model, but in adapting to local contexts and supporting communities through meaningful, place-based design and making.

How do you see the balance between local production in Fab Labs and the efficiency of global manufacturing systems?

Camprodon explained that Fab Labs were never meant to replace industrial production, but to complement it by making fabrication more accessible and distributed. While global manufacturing offers efficiency through optimization and scale, Fab Labs focus on proximity, education, and adaptability. He emphasized that sustainability is not only about where something is made, but how and why. Local production allows for experimentation, customization, and community engagement — values often missing in large-scale processes. The goal, he said, is not to reject industry, but to rethink it: to imagine hybrid systems where industrial precision meets local relevance, enabling both efficiency and resilience in production.

Platforms like PCBWay or Xometry show how process optimization can save time and resources. How can Fab Labs integrate such efficiency while keeping their open and accessible spirit?

Camprodon noted that platforms like PCBWay demonstrate the power of digital coordination, something Fab Labs can learn from. However, he stressed that efficiency in Fab Labs should serve learning and empowerment, not only productivity. Automation and optimization are valuable, but they must remain transparent — users should be able to understand and modify the process itself. He described Fab Labs as “pedagogical infrastructures” where people experiment with the same digital workflows as industry, but without the black box. By sharing open-source tools and knowledge, Fab Labs can achieve their own kind of efficiency: one based on community-driven improvement, adaptability, and local problem-solving rather than pure economic scale.

Could future Fab Labs evolve into hybrid models — local networks that are digitally connected yet still flexible and decentralized?

According to Camprodon, this vision is already emerging within the global Fab Lab and Fab City networks. He described the future of making as a distributed ecosystem where labs act as interconnected nodes rather than isolated spaces. Digital platforms allow collaboration across cities, but each lab retains its autonomy and local identity. Beyond fabrication, he emphasized that Fab Labs also act as thinking infrastructures — spaces for reflection, design, and planning rather than just production. They nurture the cultural and ethical dimensions of making, helping communities understand the systems behind technology. The Fab City model, he explained, builds on this idea: creating shared infrastructures that enable both global cooperation and deeply contextual, place-based production.