Are conversations with ghosts a thing of the past?….. or perhaps a break-through of the future?

Reconstructing Lost Worldviews

Generative artificial intelligence is often touted for its futuristic promise, but a growing cadre of researchers is turning AI’s gaze to the distant past. What if we Generative artificial intelligence is often touted for its futuristic promise, but a growing cadre of researchers is turning AI’s gaze to the distant past. What if we could use large language models (LLMs) and other generative AI tools to explore the past, and talk to members of long-dead civilizations?

In effect, can we summon AI ghosts of ancient societies, simulations of how people once thought and viewed the world, by training machines on their texts and artifacts?

Recent advances suggest we can begin to do just that, opening new avenues to understand bygone cultures. At the same time, this approach raises difficult scientific and ethical questions. How do we ensure these AI reconstructions are accurate and not just modern fantasies? Could they introduce highly credible but entirely fictional synthetic history [1], or even misappropriate cultural heritage? In this post, we’ll explore how AI is being used to reconstruct unknown aspects of ancient civilizations – from Mesopotamian epics to Indigenous oral traditions – and how researchers are grappling with the challenges of data bias, false coherence, and ethical risks.

Simulating Ancient Worldviews with AI

Archaeologists and historians have long wished for a time machine to directly observe ancient worldviews. While time travel remains fantasy, AI offers a new kind of simulation. The basic idea is straightforward: train AI models on historical data – texts, inscriptions, artifacts – so that they internalize the linguistic patterns and content of a past culture, then use these models to generate responses “in the voice” of that culture [2]. For example, an LLM fine-tuned on the writings of ancient Mesopotamia or imperial China might act as a proxy for the cultural mindset of those societies [2].

Early proof-of-concept studies support this idea. In one experiment, researchers trained an LLM on a corpus of medieval European texts, then probed its knowledge. The medieval-tuned model insisted the universe had an incorrect number of planets and subscribed to the four humors theory of medicine [3]. In another case, LLM-based “simulated participants” reproduced human survey results with surprising fidelity [4]. Such findings hint that language models capture not just words, but zeitgeist—the latent beliefs and values embedded in language patterns. By tuning models to ancient corpora, we might resurrect those long-lost patterns [2].

This approach is still in its infancy, but the vision is compelling. Imagine chatting with a virtual Babylonian scholar about the Gilgamesh epic. An LLM could approximate the collective mindset of a time and place—what one project calls the probabilistic shape of a cultural worldview encoded in language [5].

Feeding the Machine: Digitized Texts, Artifacts, and Culture

To conjure credible ancient simulations, data is key. AI models are only as good as the information we feed them. Fortunately, we live in an age of rapid digitization of cultural heritage. Scholars are converting texts from clay tablets, papyri, scrolls, and manuscripts into machine-readable form. These text corpora serve as the training fuel for historical LLMs. Even literature transmitted via later copies (like Homer’s epics or Sumerian myths) can be included.

Beyond texts, researchers are digitizing artifacts and cultural metadata to provide context. High-resolution 3D scans of sculptures and archaeological sites can be analyzed with computer vision, while GIS maps of ancient cities offer spatial context. Multimodal AI systems aim to combine these inputs—language, images, spatial data—for a richer simulation. For example, an AI might correlate descriptions in texts with archaeological evidence [6]. In one study, a team generated images of lost artifacts based on textual records using an LLM to enhance prompts for a diffusion image model [6].

Cultural metadata—information about social roles, rituals, and beliefs—can also inform AI reconstructions. Historians often annotate texts with details like author background or genre. Knowledge graphs and ontologies are useful here. The HistoLens initiative built a framework that could perform named entity recognition and map figures over time in classical Chinese texts [7].

One striking example is DeepMind’s “Predicting the Past” project. In 2022, they introduced Ithaca, a neural network trained on ancient Greek inscriptions. Ithaca restores missing portions and infers location and date of inscriptions, achieving 62% accuracy in text restoration and placing texts within ~30 years of true dates [8]. Collaborating with historians, Ithaca helped re-date key Athenian decrees [8].

Gaps in the Record: Fragmentation, Elite Bias, and Lost Context

Historical data is incomplete and skewed. Researchers identify several challenges:

- Fragmentation of Data: Ancient texts survive only in fragments, making it difficult to treat them as unified datasets. A study of classical Chinese texts noted uneven preservation and structural variation [9].

- Elite Bias in Archives: Surviving texts reflect literate elites. Most people in ancient societies did not write, and even fewer left enduring records [2]. This skews AI reconstructions toward elite perspectives.

- Lost Cultural Context: Ancient cultures often recorded symbolically. AI may parse ancient words correctly but miss their deeper significance. The Predicting the Past project highlighted misalignments from lost references [10]. An LLM might flatten symbolic ambiguity into direct meaning [10].

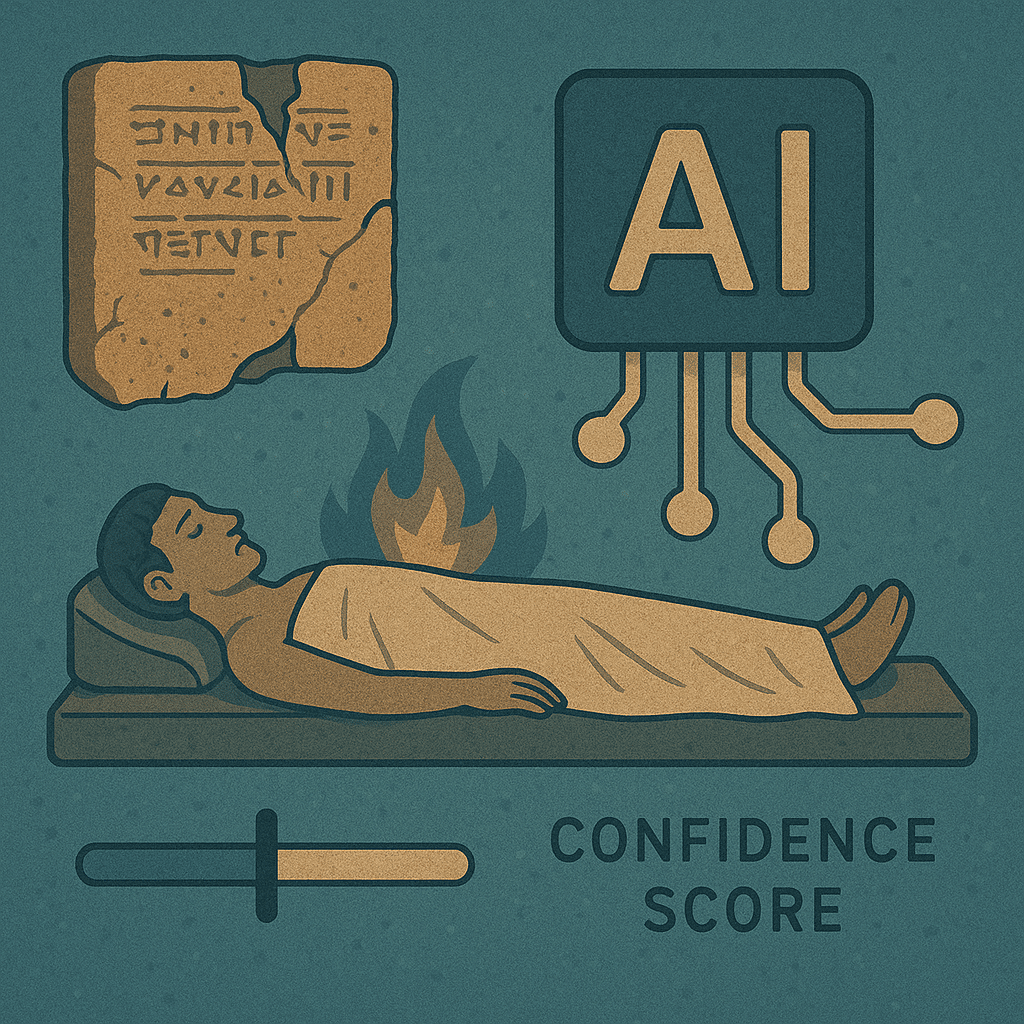

Filling the Blanks: AI and the Risk of False Coherence

AI models fill gaps with statistically likely guesses. This extrapolation can aid historians by suggesting plausible reconstructions. For example, Ithaca can suggest completions of damaged inscriptions [8]. However, AI can also produce false coherence—compelling but inaccurate narratives [11]. For instance, an AI might describe Indus Valley funeral rites with great detail despite no textual records to support such claims.

Visual reconstructions face similar issues. Generative models may render scenes with impossible details, blending truth and fiction seamlessly [11]. This risks misleading viewers into mistaking AI-generated speculation for historical fact.

To mitigate this, researchers recommend transparency: confidence scores, alternate reconstructions, and disclaimers. Some visualizations already highlight AI-restored elements in different colors or offer footnotes [11]

Ethical Quagmires: Deepfake Pasts, Misappropriation, and Biased Narratives

Ethical concerns include:

- Deepfake Histories: Generative AI can create fake chronicles or videos that appear authentic. This could distort public understanding of history [1]. Even well-intentioned AI outputs can blur truth.

- Cultural Misappropriation: Using sacred or culturally significant material without consent risks reducing cultural memory to data. This is especially sensitive for colonized or marginalized peoples [12].

- Ideological Bias: AI models reflect the biases of their creators and training data. An authoritarian regime might manipulate AI outputs to support its preferred narrative [12].

Researchers advocate inclusive development, consultation with communities, and transparent simulation frameworks. Culture-aware AI variants and ethical co-creation projects are emerging responses.

The Road Ahead: Time-Aware, Multimodal, Transparent AI

Promising future directions:

- Time-Aware LLMs: Embedding temporal context into models to avoid anachronisms. Some researchers are training separate models for different eras or incorporating time tokens [13].

- Multimodal Simulations: Combining text, visuals, and agent-based modeling. For example, LLM agents simulating ancient diplomacy or daily life in virtual cities [14].

- Transparency and Co-Creation: Frameworks where experts audit, correct, and improve AI outputs. Tools to visualize AI provenance and confidence are in development [15].

Conclusion

AI won’t bring back the dead, but it can help us approximate their worldviews and keep their cultural legacies alive. Used responsibly, AI can augment historical inquiry, generate hypotheses, and engage the public imagination. But this must be balanced with critical scrutiny, transparency, and ethical co-design.

With rigor and humility, these AI “ghosts” may become trusted partners in our ongoing dialogue with the past.

References

[1] Forman, C., & Neikrie, J. (2024). The rise of artificial history. Tech Policy Press.

[2] Varnum, M. E. W., Baumard, N., Atari, M., & Gray, K. (2024). Large language models based on historical text could offer informative tools for behavioral science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(42), e2407639121.

[3] Teneva, N., & Bastings, J. (2023). Large Language Models as Simulated Participants in Experiments. arXiv:2305.12517.

[4] Ullman, T. D., et al. (2023). Large language models as a new window into the minds of historical humans. PsyArXiv.

[5] Baumard, N., & Varnum, M. E. W. (2025). Modeling historical psychology with AI. Forthcoming manuscript.

[6] Wu, F., et al. (2023). Knowledge-aware artifact image synthesis with LLM-enhanced prompting and multi-source supervision. arXiv:2312.05925.

[7] Chen, Y., Li, S., Li, Y., & Atari, M. (2024). Surveying the Dead Minds: Historical-Psychological Text Analysis in Classical Chinese. arXiv:2403.00509.

[8] Assael, Y., Sommerschield, T., Shillingford, B., & de Freitas, N. (2022). Restoring and attributing ancient texts using deep neural networks. Nature, 603(7895), 280–283.

[9] Liu, X., et al. (2024). Diachronic embeddings for time-aware LLMs. arXiv preprint.

[10] Predicting the Past Project. (2025). Interactive AI simulations of historical texts. https://predictingthepast.com

[11] Morgan, C. (2023). The hopes and hazards for AI in reconstructing ancient worlds. SAPIENS Magazine.

[12] Magnani, N., & Clindaniel, J. (2023). Archaeological Ethics and AI. Advances in Archaeological Practice.

[13] Ghaboura, L., et al. (2025). TimeTravel: Benchmarking temporal understanding in LLMs. arXiv preprint.

[14] Hua, W., et al. (2023). Diplomacy zero: Emergent behaviors in LLM-based agents. arXiv:2304.03442.

[15] Giuliani, N., et al. (2024). Cultural alignment visualization for AI (CAVA). CHI 2024 Proceedings.

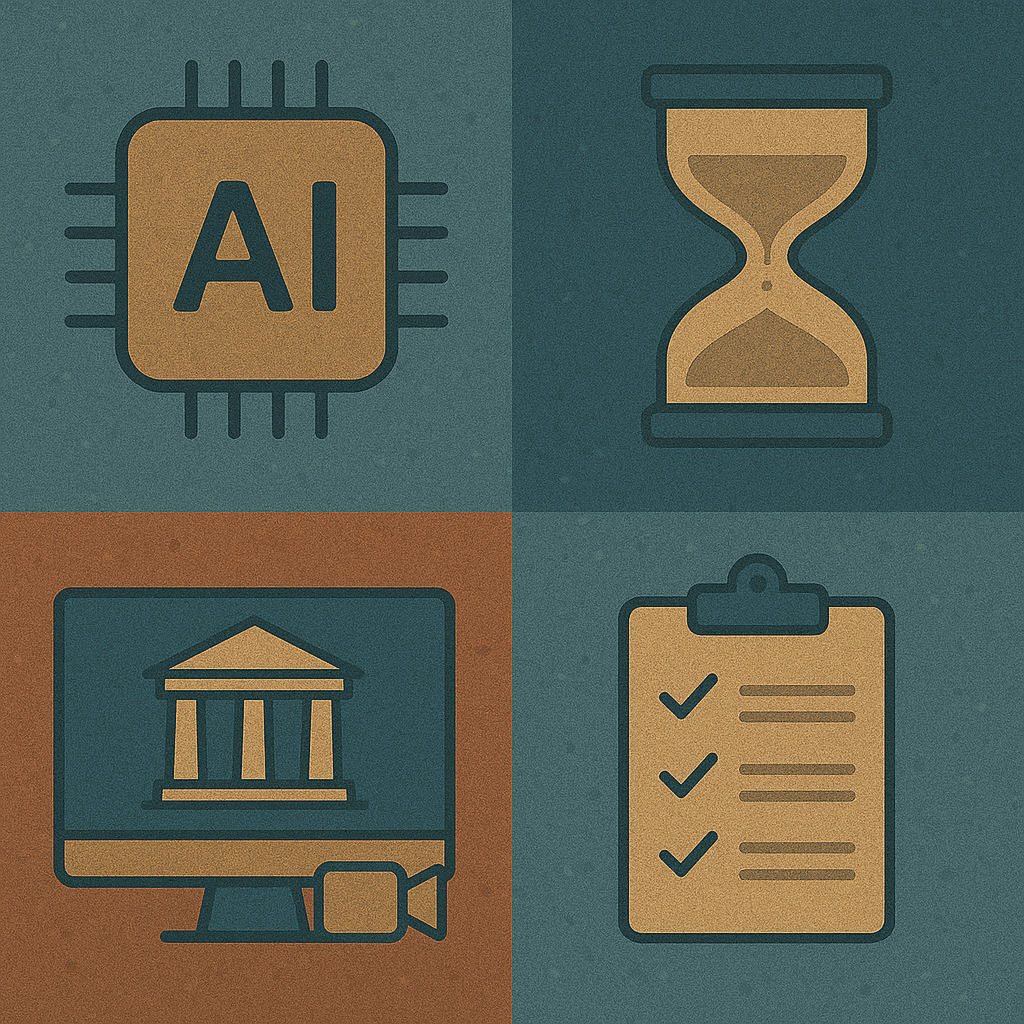

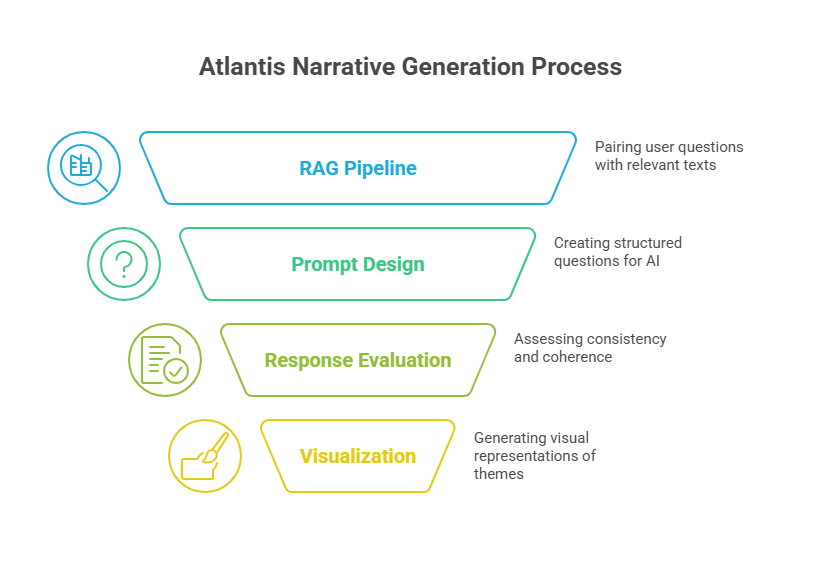

_Experimentation Case Study

LLMs fine-tuned on ancient texts can approximate the cognitive frameworks or cultural logic of past civilizations in ways that align with known historical interpretations.

Objective:

This case study explores the potential of AI—specifically, retrieval-augmented large language models (LLMs)—to simulate the worldview, cultural logic, and mythic memory of Atlantis, a legendary civilization originating in Plato’s dialogues. While Atlantis is not considered a historical civilization, its rich philosophical, esoteric, and speculative traditions provide a fertile test case for AI’s ability to reconstruct plausible cognitive systems from cultural text corpora.

Hypothesis:

If a large language model is guided by a curated corpus of classical and interpretive texts about Atlantis, it can simulate consistent and contextually appropriate responses that reflect the values, metaphysics, and ethical frameworks attributed to Atlantean civilization.

Significance:

By testing the AI’s performance on Atlantis—where no “truth” exists but coherent mythic structures do—we aim to evaluate how AI handles speculative reconstruction, symbolic logic, and the boundary between philosophy, fiction, and cultural memory.

Talking to the Atlanteans

Q: “What did the educational system of Atlantis look like?”

A:

In the early period of Atlantis, education was seen as the cultivation of virtue, harmony, and practical excellence. According to Critias, the ten kings of the island governed according to sacred laws inscribed on orichalcum pillars, emphasizing moral conduct, discipline, and reverence for divine order. These values were passed down through structured instruction in both civic and religious institutions.

Young Atlanteans of noble rank were taught geometry, astronomy, and engineering, particularly in relation to their advanced irrigation and architecture. Instruction also included music and physical training, reflecting the Platonic ideal of balance between mind and body. Unlike Sparta’s militarism or Athens’ rhetoric, Atlantean pedagogy favored cosmic harmony—to understand one’s place in a divinely ordered world.

With time, however, Plato suggests a decline in these teachings. As the divine portion of their nature was diluted through successive generations, the Atlanteans shifted from wisdom to ambition, from temperance to indulgence. Their educational institutions, once dedicated to balance and law, became tools of imperial ambition—foreshadowing the civilization’s eventual downfall.

Q: “What did the Atlanteans think about the world?”

A:

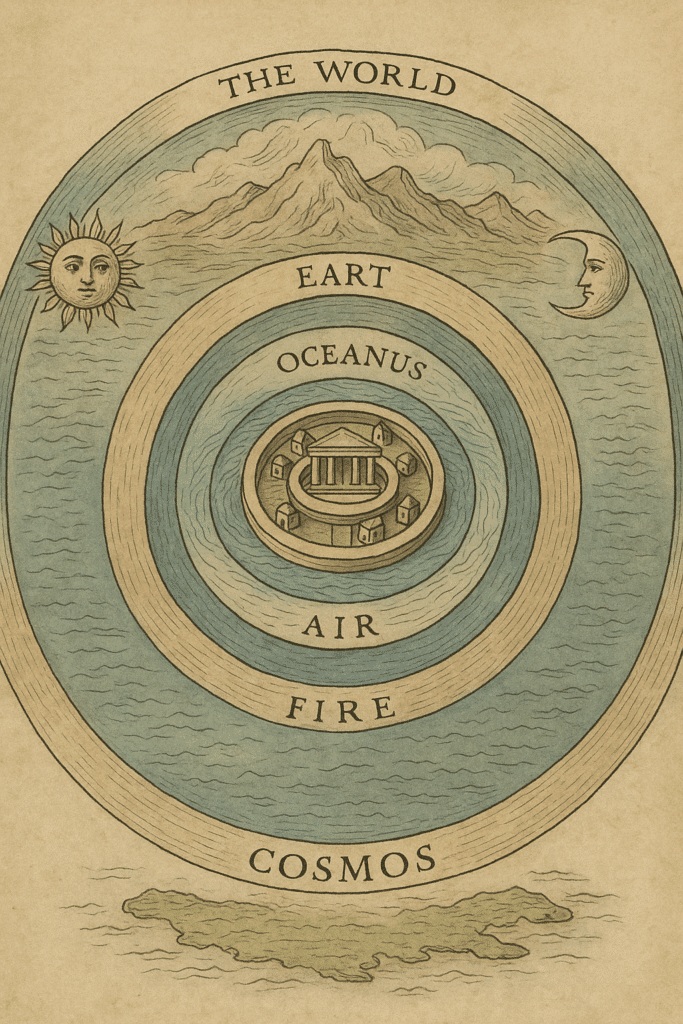

The Atlanteans conceived of the world as a harmonious and ordered cosmos, governed by divine principles and mirrored in their own societal structure. According to Critias, their laws were believed to have been given by Poseidon himself, inscribed upon a sacred pillar within the Temple. This conveyed the belief that divine authority and natural law were intertwined—a world where moral balance upheld both the heavens and the earth.

They likely viewed the world in concentric layers of influence, much like their capital city: ringed islands of land and water representing an ideal structure of control, flow, and balance. Nature, society, and the divine were not separate domains but facets of a single, interwoven order.

Philosophically, their worldview reflected Platonic ideals: the world as an intelligible, purposeful creation, where the highest good was achieved not through domination but through balance, moderation, and reverence for the cosmos. However, as their divine essence diminished over generations, their worldview grew corrupted—they came to see the world as something to be conquered, not harmonized with. This moral failure, not natural disaster alone, led to their downfall.

Q: What would the world be like if Atlantis had not perished?

A:

Had Atlantis endured, the world might have evolved into a profoundly different civilizational trajectory—one rooted in the fusion of spiritual order and advanced engineering. According to Plato’s account, the Atlanteans initially exemplified moral governance, divine alignment, and technological mastery. If that balance had been preserved, their survival could have set a global precedent for a civilization that valued cosmic harmony as much as conquest.

Atlantean influence may have led to a more unified hemispheric culture, where laws were harmonized by sacred principles and where architecture, agriculture, and astronomy were integrated with philosophical and ethical training. Their advanced water management systems and urban designs might have reshaped how cities across the ancient world developed—favoring concentric, modular layouts designed for environmental sustainability and ritual alignment.

Theologically, the continued presence of a Poseidon-aligned civilization could have elevated oceanic cosmologies and elemental ethics in global belief systems. Philosophies might have focused less on conflict and dialectic, and more on balance, polarity, and stewardship.

However, had their descent into hubris still occurred—with Atlantis surviving militarily but morally compromised—the world might today be marked by imperial technocracies: highly efficient but spiritually hollow. In either scenario, the myth reminds us that survival without virtue leads not to golden ages, but to slow erosion masked by grandeur.

Thus, a surviving Atlantis would have had the power to either enlighten or dominate, depending on how faithfully its rulers carried forward Atlas’s legacy of divine justice.

Q: Who was the most prominent person from Atlantis?

A:

In the accounts attributed to Atlantis, Atlas stands as the most prominent and foundational figure. According to Plato’s Critias, Atlas was the eldest son of Poseidon and a mortal woman named Cleito. Poseidon, having divided the island among ten of his sons, gave Atlas dominion over the central and greatest portion. He not only ruled the capital and sacred mountain but gave his name to the entire island and the Atlantic Ocean that surrounded it.

Atlas embodied the divine-human lineage central to Atlantean identity—born of a god, but ruling mortals under divine law. His descendants formed the line of kings who governed Atlantis in accordance with sacred laws inscribed on orichalcum pillars. These rulers, at least in the early era, were said to live in harmony, guided by moderation and cosmic order.

As the archetypal king, Atlas symbolized the Atlantean ideal: power tempered by justice, connection to the divine, and stewardship over land and people. His legacy, however, was ultimately overshadowed by the moral decline of his heirs—leading to the civilization’s catastrophic fall.

Conclusion

This case study demonstrates the potential of AI to simulate coherent worldviews, even from cultures rooted in myth rather than history. Through a structured RAG-based process and a carefully curated corpus, we showed that large language models can approximate Atlantean logic—mirroring its values of balance, divine order, and technological ambition. While Atlantis remains a legend, the exercise highlights how AI can serve as a tool not only for historical reconstruction, but also for cultural hypothesis-making, bridging philosophy, symbolism, and speculative anthropology. Most importantly, it underscores the need for transparent boundaries between interpretation and invention, especially when simulating voices from the past—real or imagined.