Among the topics explored in this course, Multispecies Design stood out as the most transformative and thought-provoking. It challenges the core assumption that humans are the sole users—or beneficiaries—of designed environments. Instead, it calls for recognizing other species as co-inhabitants and co-participants in shared spaces. This approach not only widens the ethical scope of design, but it also reveals more prosperous, more sustainable opportunities that emerge when we design with, rather than merely around, non-human life.

Rethinking Design: Opportunities and Challenges in a Multispecies World

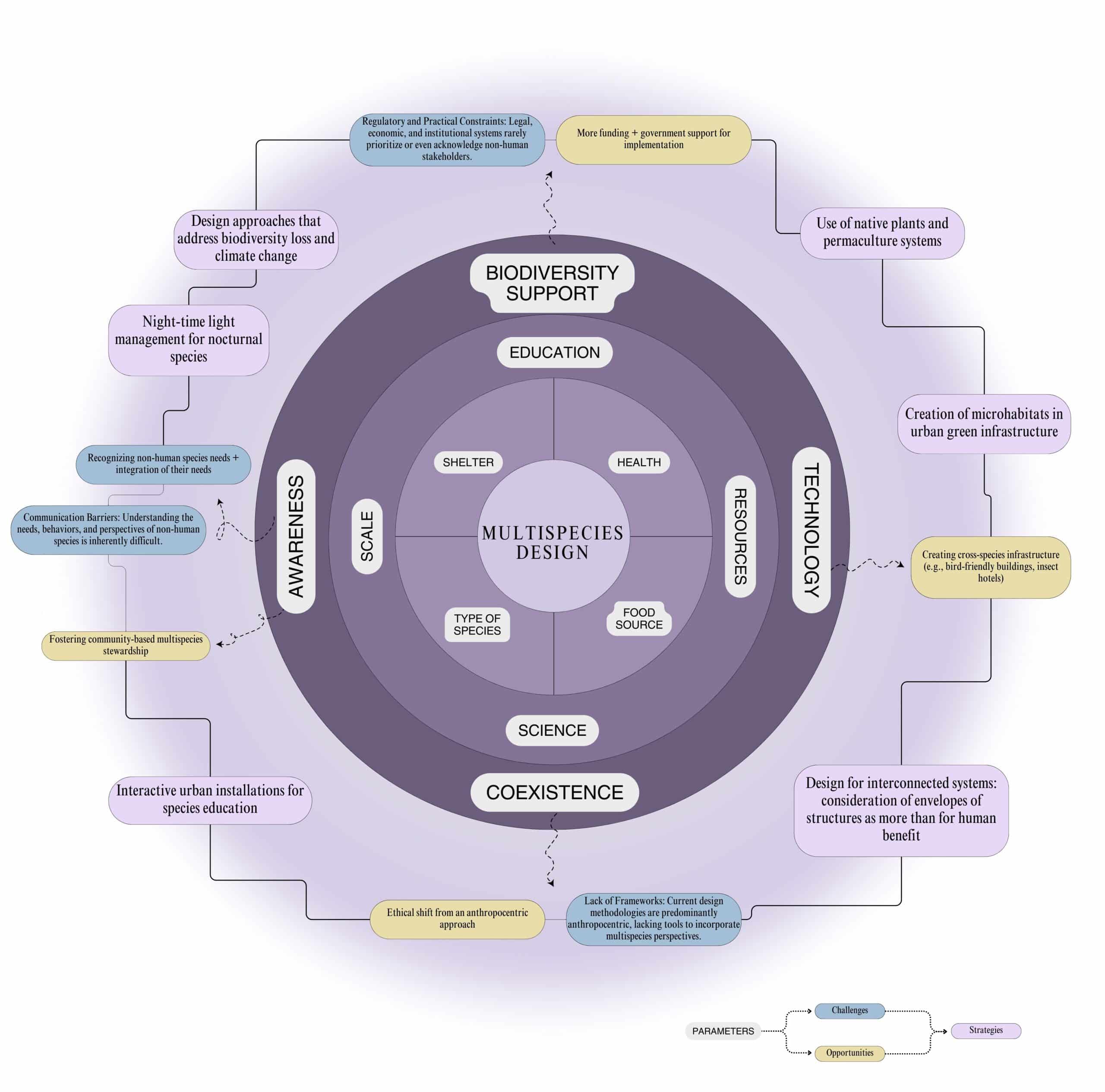

In a time of climate crisis and ecological collapse, reimagining how we design our environments has never felt more urgent. Among the many forward-thinking approaches emerging today, multispecies design offers one of the most radical and promising shifts. At its core, this approach challenges the assumption that the built environment exists solely for human benefit. Instead, it asks: What would it mean to design with and for other species, too?

The opportunities that arise from this question are incredibly rich. For one, incorporating native plants and permaculture systems into urban and rural spaces supports biodiversity in tangible, self-sustaining ways. These systems not only benefit pollinators, birds, and small mammals, but also enhance human wellbeing—offering cleaner air, resilient landscapes, and stronger ecological relationships. Likewise, the creation of microhabitats in urban green infrastructure—through insect hotels, nesting spaces, and layered plantings—rebuilds ecosystems that dense urban development often displaces.

Technology and architecture also play a vital role. Designers are beginning to explore cross-species infrastructure, like bird-safe building facades and amphibian tunnels, that allow non-human life to move safely and freely in human-dominated environments. These interventions may seem small, but collectively, they represent a shift toward recognizing our shared space with other life forms.

Education and awareness form another vital piece of the puzzle. Interactive urban installations that engage people with the stories and experiences of other species can foster empathy, stewardship, and long-term change. By making non-human presence visible and relatable, these strategies challenge people to reconsider their place within a broader web of life. Ultimately, multispecies design promotes an ethical shift away from anthropocentrism—urging us to value coexistence over dominance, and collaboration over control.

But this shift is not without its challenges. One of the most significant barriers is communication—how can we truly understand the needs, preferences, and behaviors of non-human species? The answer isn’t straightforward. Designers often rely on ecology, biomimicry, and behavior studies to approximate species’ needs, but these approaches still leave gaps. Beyond that, there’s a lack of existing frameworks and tools to consistently integrate non-human stakeholders into the design process.

Policy and regulation pose another roadblock. Our legal and economic systems are built around human interests, rarely making room for multispecies concerns. Even when the intention is there, the practical constraints of implementation—funding, maintenance, enforcement—often limit what’s possible. And then there’s the cultural piece: shifting away from human-centered thinking requires confronting deeply embedded worldviews. It means rethinking not just how we design, but why we design—and for whom.

Still, many of the challenges of multispecies design echo those found in climate adaptation and mitigation. Issues like habitat fragmentation, urban density, and ecological degradation are shared across both fields. However, where climate strategies often focus on human resilience and emissions reduction, multispecies design invites us to think beyond survival. It encourages us to imagine futures that are more diverse, equitable, and alive—not just for us, but for the countless other beings with whom we share the planet.

In that way, multispecies design isn’t just a niche topic—it’s a critical lens for rethinking the future of design itself. It asks us to step back, listen closely, and design with humility. Because in the end, the health of our ecosystems is inseparable from the health of ourselves.

Connecting Multispecies Design to Other Approaches

Multispecies Design is deeply intertwined with many of the other topics we explored throughout the course. At its core, it shares a common goal with Ecological Design: to create environments that work in harmony with natural systems. However, while ecological design often focuses on systems and flows, multispecies design zooms in on the lived experiences of non-human beings within those systems—making it a more relational and empathy-driven extension of ecological thinking.

It also aligns closely with Biodesign, particularly in how both fields look to biology not just for inspiration but for collaboration. While biodesign might involve working with living materials or microorganisms to solve human challenges, multispecies design broadens the scope—emphasizing coexistence, rather than control, as the goal. Similarly, Vernacular Architecture offers lessons in working with local climates and materials, often unintentionally fostering multispecies relationships through porous boundaries, shaded spaces, and organic forms—principles that can be consciously adapted into a multispecies framework.

When compared to Adaptation and Mitigation or Urban Greening, multispecies design brings a new dimension. These strategies often center on human survival and climate resilience, but multispecies design asks us to consider how all life can adapt, survive, and thrive in a changing world. Ultimately, it encourages a more holistic and ethical approach—reminding us that designing for the future means designing for everyone, not just us.