In today’s climate-conscious world, industries and governments alike are actively aligning their strategies toward climate adaptation and mitigation. The urgency of the climate crisis has unified efforts across disciplines, yet many responses tend to focus on highly specific, niche areas of research and intervention. While such targeted approaches are undoubtedly valuable, they often risk overlooking the broader context. This blog explores climate adaptation and mitigation from a wider perspective—emphasizing the importance of stepping back to understand how different fields, solutions, and systems intersect. By adopting this broader lens, it becomes possible to better recognize the interdisciplinary nature of the challenge and ensure that time and resources are invested in ways that are both strategic and impactful. This shift in perspective is essential for guiding more effective action and fostering long-term resilience in an increasingly complex climate landscape.

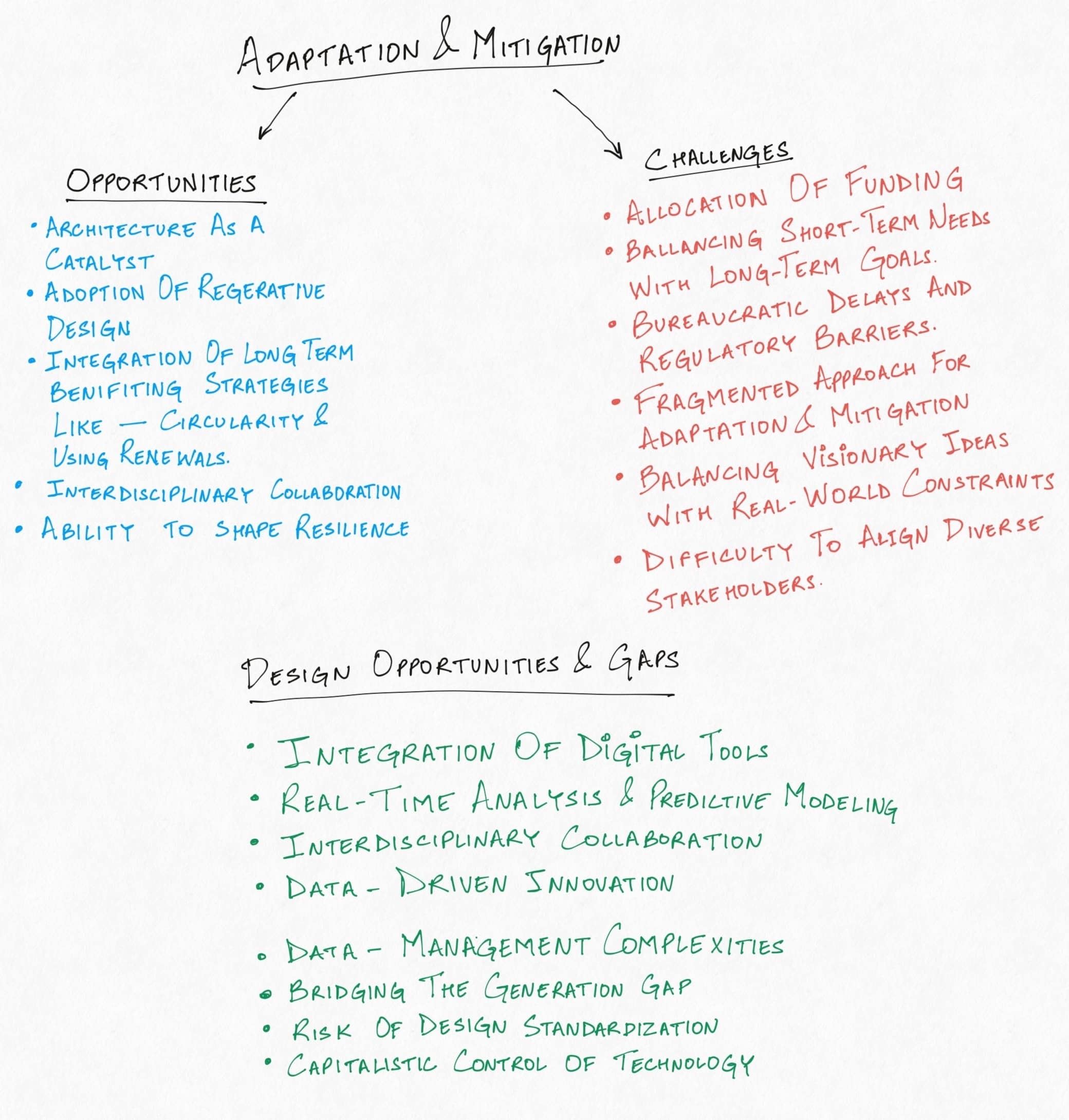

Within the field of architecture, climate adaptation and mitigation present both significant opportunities and complex challenges. These global imperatives position architects as crucial contributors to systemic change, reimagining not only buildings but also the broader networks and relationships that define the built environment. Opportunities lie in the adoption of regenerative design principles, passive strategies, renewable technologies, and circular material practices. Architecture, in this context, has the potential to act as a catalyst for interdisciplinary collaboration, bringing together engineers, ecologists, policymakers, and communities to co-create resilient, low-carbon futures.

However, translating these opportunities into reality is often obstructed by practical and institutional barriers. Funding allocation for climate-resilient architecture remains inconsistent, with projects frequently constrained by short-term budgeting, limited public investment, or the absence of financial incentives for long-term sustainability. In addition, navigating bureaucratic processes, such as permitting delays, outdated codes, and rigid regulatory frameworks, can impede the timely implementation of innovative climate strategies. These systemic challenges, coupled with the tendency to address adaptation and mitigation as separate efforts, can lead to fragmented outcomes. Architects are therefore required to balance creative and forward-thinking solutions with the realities of bureaucracy, funding limitations, and policy constraints. In this context, adopting a systems-thinking approach becomes not only beneficial but essential, allowing the discipline to engage more holistically with the climate crisis and ensure that architectural responses are both effective and enduring.

The intersection of design, technology, and climate action opens up a rich landscape of opportunities, yet it also reveals critical gaps that demand careful attention. Emerging digital tools, such as digital twins, parametric platforms, and performance simulation software, offer immense potential for integrating large, multidisciplinary datasets into adaptive and mitigation-focused design processes. These technologies enable real-time analysis, predictive modeling, and systems-level thinking that are essential for addressing the complexity of climate-responsive architecture. However, the implementation of such tools is not without challenges. High data dependency, lack of interoperability, and the steep learning curve associated with digital integration can derail projects, especially when design teams are expected to manage diverse streams of information across disciplines.

Moreover, there exists a growing disconnect between digitally skilled younger professionals and more experienced practitioners who possess a wealth of contextual knowledge and judgment. Bridging this generational gap is crucial to fostering continuous innovation that is both technologically agile and grounded in real-world wisdom. Yet, the increased reliance on digital workflows also brings the risk of design standardization, where optimized outputs are prioritized over spatial or cultural specificity, leading to solutions that may lack creativity, identity, or local relevance. Compounding these issues is the influence of market forces. In a capital-driven system, there is a risk that powerful stakeholders may co-opt digital infrastructures to serve narrow interests, manipulating outcomes and reinforcing inequities under the guise of efficiency. These challenges underscore the need to critically assess how design technologies are adopted, who controls them, and whether they truly serve the broader goals of equity, resilience, and sustainability.

Adaptation and mitigation serve as unifying strategies that connect ecological design, multispecies design, biodesign, vernacular architecture, and urban greening under a single framework for sustainable living. By responding to environmental challenges, adaptation ensures that human and non-human systems can thrive in changing conditions, integrating nature-based solutions and resilient design principles. Mitigation, on the other hand, reduces environmental impact through regenerative practices, energy efficiency, and climate-conscious innovation. Together, these approaches foster built environments that harmonize with ecosystems, promote biodiversity, and embrace local knowledge, ensuring a sustainable and inclusive future.