Architecture as a means of social segregation

“capital materializes, to a large extent, through urban construction, the establishment of social relations in the city, the organization of space in the city, among others”

(Harvey 2020, 23)

According to Charles Jencks, the death of the modern architecture dated on July 15, 1972 at 3:32 p.m, when the famous Pruitt Igoe was demolished. For Jecks this act symbolized the collapse of the modernism’s promesses. With its decline, the emergence of radical imaginaries that respond to the new booming economic model, was needed and urgent. Seventeen years later, on August 17, 1989, neoliberal architecture was born, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The signing of President Carlos S. Menem on the State Reform law, initiated a period of state privatization, which resulted in real estate speculation and urban segregation.

From the rubble of the failed utopia of modernism emerged the cult to fictitious capital. Through the lens of film and theory, it unpacks how the financial imaginaries materialized in urban enclaves, operate as “truth games” (Spencer, 2016), infiltrating the urban environment under ideas of progress and emancipation.

This essay is framed in the Argentinian neoliberal period, under Menem´s presidency between 1989-1999. The analysis is structured around three of neoliberalism’s “commandments,” each illustrated by a case study, a cinematic analogy, and a theoretical framework.

Commandment 3: The market regulates itself

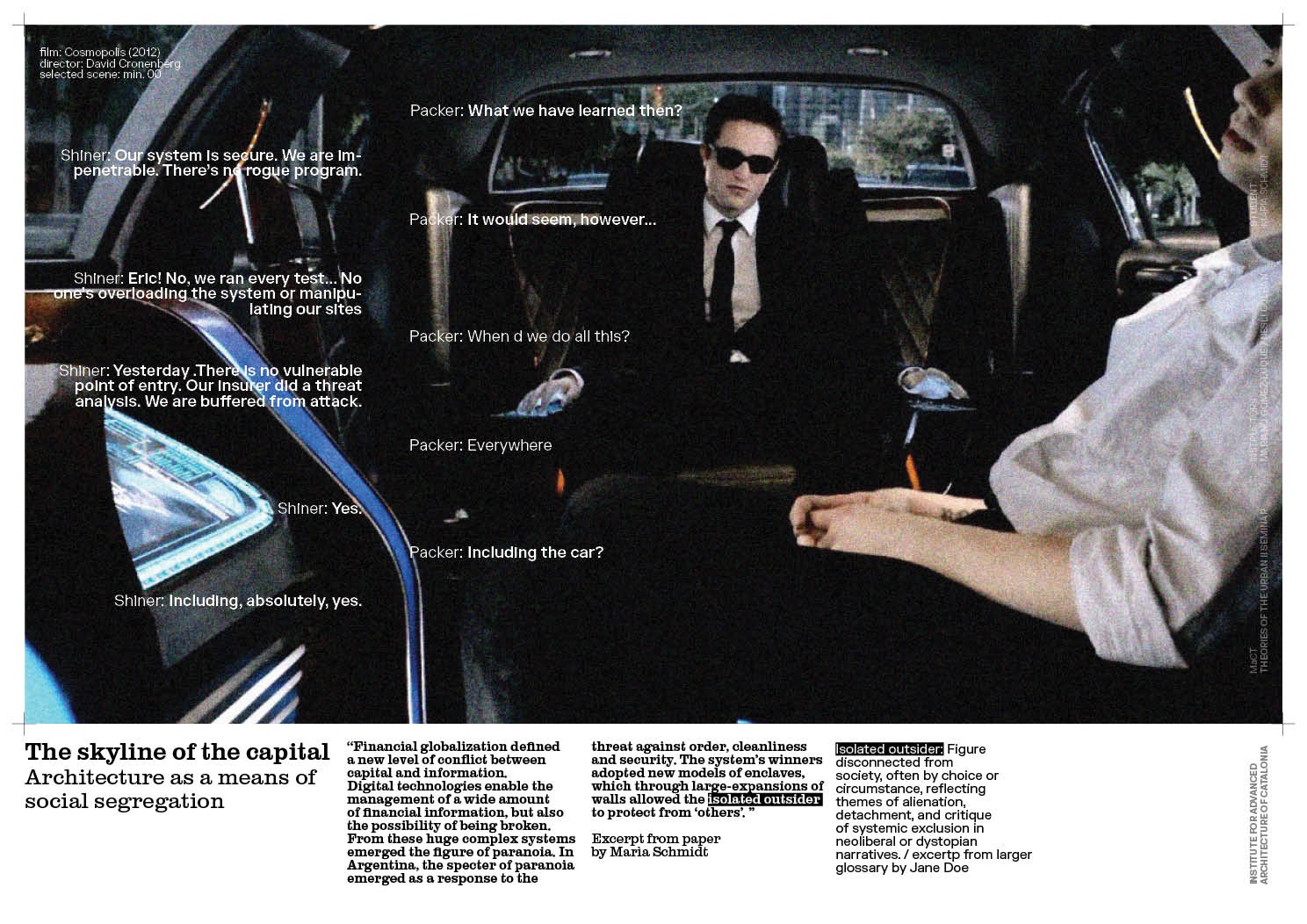

The financial globalization defined a new level of conflict between the capital and the information. The new economical dynamic of global cities demanded new functions and therefore new architectural and urban programs. Private life gained preponderance, generating “spatiality of the private” in the public domain, in terms of private property and private appropriation: services and facilities.

It is well known that, far from regulating itself, the market, when it has autonomy, produces the greatest brutalities in the name of progress and freedom. The neoliberal urbanism in Argentina, embodied by different enclaves reveals the contradictions of a system that promised progress but delivered exclusion. As films like Cosmopolis suggest, these spaces are not just architectural forms but machines for living separately, reproducing the inequalities of a globalized economy.