In the shadowed canyons of our cities, where steel and glass rise like silent titans, the air hangs heavy—each breath a subtle pact with progress. Urban heat islands amplify this weight, pushing temperatures 5-10°C higher than surrounding areas, choking the atmosphere with invisible heat (McDonald et al. 2016, 48). Yet, amid this urban monochrome, a quiet rebellion emerges: urban greening, a living pigment brushed across concrete expanses. It’s not mere decoration—it’s a requiem for lost roots, a calculated effort to restore life where asphalt dominates. As I explore ecological design at IAAC, cities transform in my mind—not as static grids, but as dynamic canvases craving nature’s touch, like Monet’s water lilies softening stone edges. Beyond the poetry, urban greening is a science, demanding precision and planning to revive the city’s pulse.

Why Urban Greening Captivates Me

Urban greening captivates me because it’s a poetic defiance against urban sterility—a way to thread vitality into the city’s fabric. It confronts silent struggles: stifling heat, air thick with particulate matter, and the isolation of gray streets. Imagine rooftops blooming with wildflowers, walls draped in ivy, and neglected corners reborn as green sanctuaries. This isn’t just aesthetics; it’s about forging spaces where nature and humanity breathe together. Research shows urban green spaces can reduce cortisol levels by up to 10%, easing the mental toll of city life (Wolch, Byrne, and Newell 2014, 238). As an enthusiast of adaptive systems, I see urban greening as more than sustainability—it’s about crafting cities that live, responding to the rhythms of both earth and inhabitant.

The Challenges: Nature’s Tug-of-War with the Urban Grid

Integrating nature into cities is a complex dance. Urban greening contends with rigid infrastructure—impervious surfaces, resource demands, and uneven access. Plants must root in soils where concrete resists, often requiring 4-6 liters of water per square meter daily, a heavy draw on municipal supplies in dry regions (Dunnett and Kingsbury 2008, 75). Equity casts another shadow: green spaces tend to flourish where wealth already thrives, leaving underserved areas barren. These obstacles aren’t dead ends; they’re prompts to innovate—pushing us to rethink how nature can adapt within the urban frame.

The Opportunities: A Promise of Renewal

The rewards of urban greening outweigh its trials. Green roofs can slash surface temperatures by up to 30°C, cooling the city’s fevered brow (McDonald et al. 2016, 48). Vegetation traps 0.2 kg of particulate matter per square meter annually, purging the air of its unseen burden (McDonald et al. 2016, 50). Biodiversity thrives, too—pocket parks can boost urban wildlife by 20-30%, coaxing birds and pollinators back into the concrete fold (Beatley 2011, 112). For residents, it’s a lifeline: calming minds, lifting spirits, and weaving communities closer. Urban greening reimagines the city as a living entity—one that grows and heals in tandem with us.

Mapping – Selecting Techniques for the Green Future: A Vision in Bloom

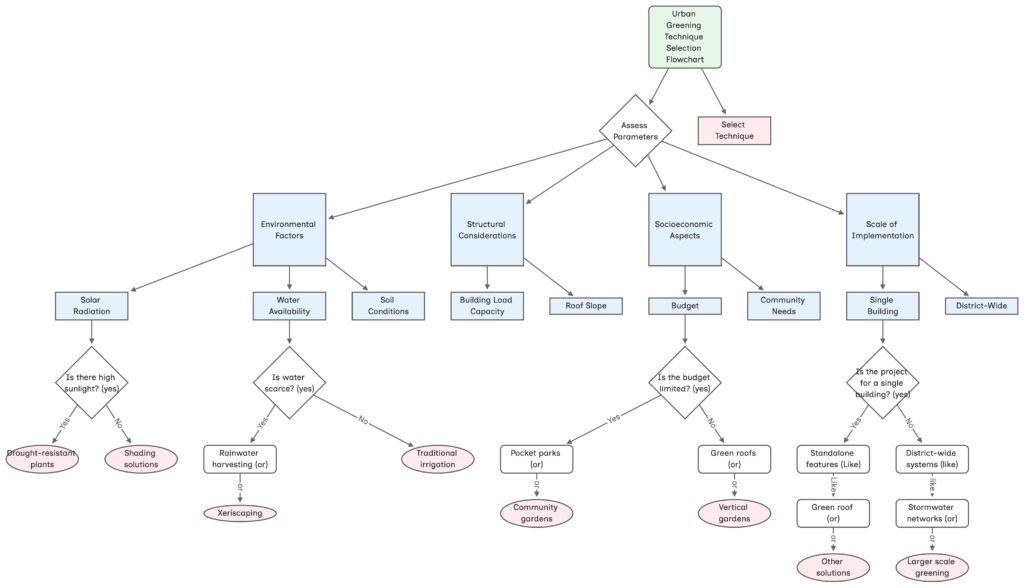

Selecting techniques for urban greening requires a detailed assessment of various parameters to ensure that the methods chosen align with both the specific goals of a project and the characteristics of the target area. Environmental factors—such as solar radiation, water availability, and soil conditions—are critical, as they determine plant survival and irrigation demands; for example, high-sunlight zones may need drought-resistant plants or shading solutions, while water-scarce regions could benefit from rainwater harvesting or xeriscaping. Structural considerations, including building load capacity and roof slope, influence the practicality of options like green roofs or vertical gardens. Socioeconomic aspects, such as budget limitations and community needs, also shape decisions—affordable approaches like pocket parks or community gardens can meet ecological and social objectives, especially in underserved neighborhoods. Additionally, the scale of implementation matters: a single building might use a standalone green feature, whereas a district-wide project could leverage integrated systems like stormwater management networks. By balancing these parameters, the selection process optimizes ecological benefits—such as reducing urban heat and boosting biodiversity—while addressing practical constraints, ensuring a sustainable and effective greening strategy tailored to the area and its goals.

Urban greening isn’t just a technical exercise—it’s a thread in a richer tapestry of design and ecology. It reflects ecological design, aligning human ambition with nature’s systems. It supports multispecies design, creating habitats amid urban sprawl—green corridors can lift pollinator numbers by 20%, nurturing biodiversity in city cores (Beatley 2011, 113). Biodesign hints at innovations like mycelium panels, which insulate and decompose naturally, easing environmental strain. Vernacular architecture inspires with shaded courtyards, reimagined for modern streets. In the interplay of adaptation and mitigation, urban greening does both—relieving current pressures while preparing cities for future shifts. It mirrors my passion for adaptive systems, urging spaces that evolve with time.

A Call to Reimagine Our Cities

Urban greening is no passing fad—it’s a lifeline, painting vitality onto the concrete canvas. Its challenges are real, but its promise is a flourishing urban tomorrow. At the intersection of ecology and architecture, let’s envision cities not as machines, but as organisms—pulsing with green, breathing alongside us. The future needn’t be gray; it can be verdant. Could your next project feature a green roof or a community garden in a neglected corner? What role will you play in this living transformation?