Our research on the El Raval neighborhood explored the tensions and opportunities between residents and tourists, two populations who travel from all over the world to be in El Raval. While tourists and residents can have conflicting priorities and demands of their environment, the two are also dependent on each other and we came upon creative interventions that cater to both groups.

El Raval’s development is deeply connected to Barcelona’s industrialization and urban evolution. In the 18th century, the neighborhood was formally integrated into the city through urban planning, and its low rents soon attracted workers and immigrants fleeing rural poverty. As Barcelona’s industries expanded in the 19th century, El Raval, with its proximity to factories and the port, became an ideal location for the growing labor force. The area transformed into a densely populated working-class district, with textile mills, workshops, and manufacturing plants thriving amidst its narrow, shadowed streets. Despite this economic activity, overcrowding and poor living conditions became defining aspects of the neighborhood. In the late 19th century, even as the neighborhood retained its gritty character, it saw a touch of creativity when Antoni Gaudí built Palau Güell. In the late 20th century urban revitalization projects introduced cultural hubs and renovated buildings, transforming El Raval into a vibrant, multicultural center of art and life.

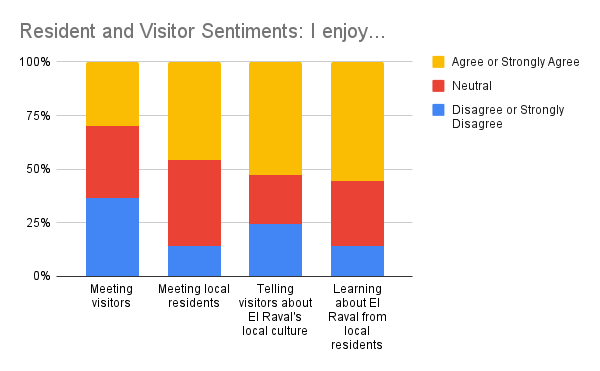

We started our analysis by conducting a broad review of articles, policies, and studies related to the neighborhood. News stories focused on the latest developments of the nightlife and entertainment scene, announcing new restaurants, live music performances, and updates on local celebrities. There were also many stories about crime and safety in the area, focusing on graffiti, counterfeit goods, and drug use. Another common theme was housing insecurity in the area and socioeconomic vulnerability. The studies of El Raval that we reviewed opened up a major theme: tourism. In particular, there was an interesting focus on the perceptions of residents and tourists in El Raval of the neighborhood and each other: tourists heavily overestimated resident willingness to engage with them, while residents underestimated tourist’s desire to engage with residents. The findings demonstrated that despite misperceptions on both ends, the study identified interesting opportunities for tourists and residents to come together to build a positive relationship through creative tourism.

The policies relevant to El Raval demonstrate the relationship of the neighborhood to the greater city, and highlight strategic priorities and challenges the neighborhood faces. According to the Barcelona Tourism Strategic Plan, tourist resources in the city create overcrowding problems and community disputes between tourists and residents, in areas including El Raval. “Despite the management efforts made over the last few years, this phenomenon of concentration, instead of improving, appears to be on the rise, extending to other zones and areas in the city, certainly due to the great rise in numbers of visitors and tourists” (p31, Barcelona Tourism Strategic Plan 2020). Tourism is linked to the strained local housing supply, with a report from the Barcelona City Council stating, “The city’s residential rental market shows there has also been a rise in prices and a reduction in supply in the neighborhoods with the most tourist activities, although the cause for that cannot be directly attributed to it” (p32, Barcelona Tourism Strategic Plan).

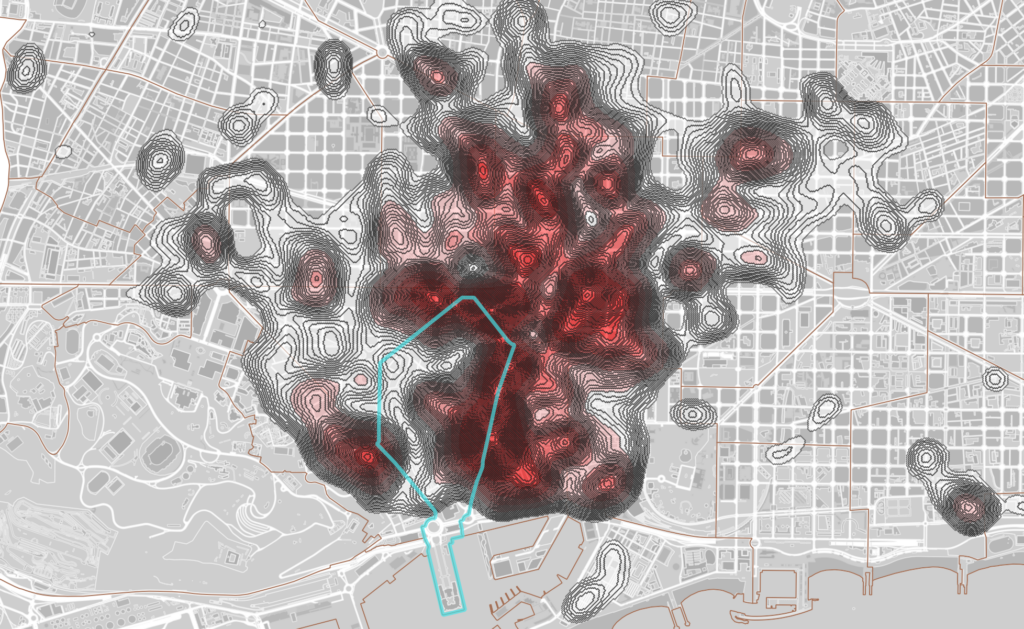

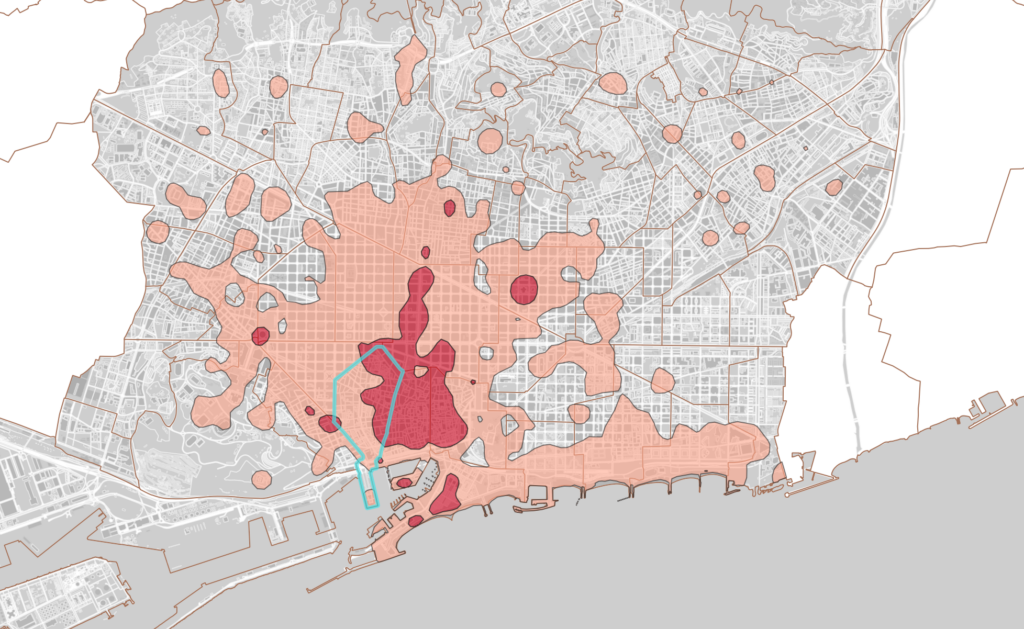

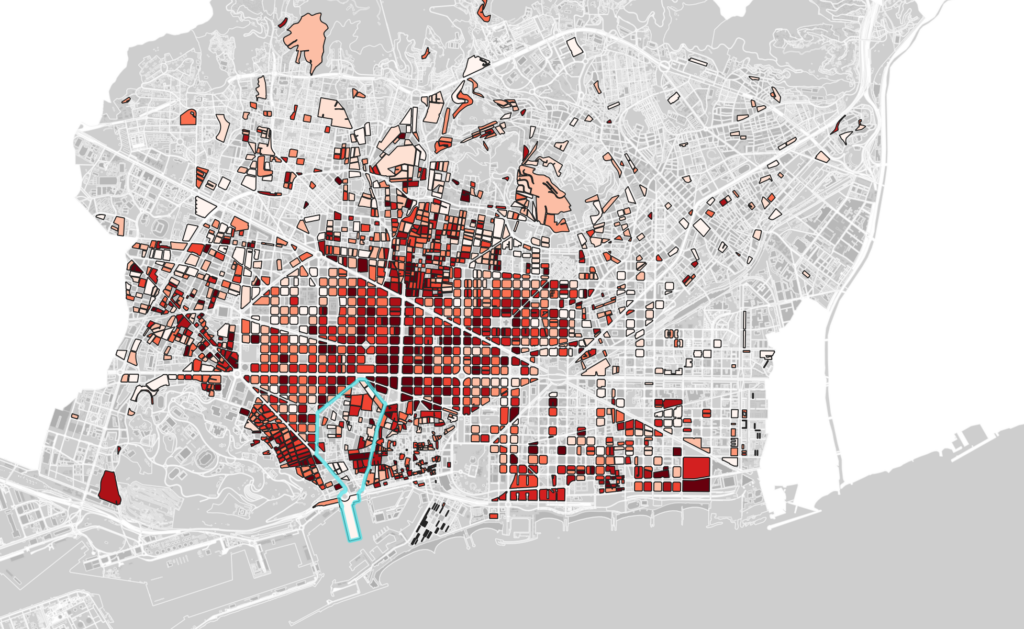

When we explored data on tourism available from municipal data sets, our results underscored how crucial the tourism industry and its physical and cultural effects are for El Raval. In the tourism intensity contour map, several peaks are shown in the periphery of El Raval, particularly around sites like the Cinema Floridablanca, the area of Plaça Catalunya and Plaça Universitat, all along La Rambla with a concentration around Plaça Reial, and at Montjuic towards the south. As shown in the contour map of the impacts of tourism, almost half of El Raval is considered to have the highest index of touristic impact, 3, while the rest of it is shown at the second level.

The Barcelona Tourism Strategic plan commits to certain measures to alleviate the effect of tourism in El Raval, like the creation of the City and Tourism Economic Fund and promoting new business initiatives that create jobs without monopolizing housing or urban spaces (p125, Barcelona Tourism Strategic Plan). It also proposes feasibility studies to explore the potential of Tourist Housing Units (HUTs) to be converted to social housing (p103, Barcelona Tourism Strategic Plan). On the other hand, other plans like the Barcelona Sustainable Tourism Strategy 2023 specifically do not include El Raval in their 41M EUR investments, opting to promote economic resilience in burdened neighborhoods through tourism decentralization (p3, Barcelona’s Strategy for Sustainable Destination Tourism).

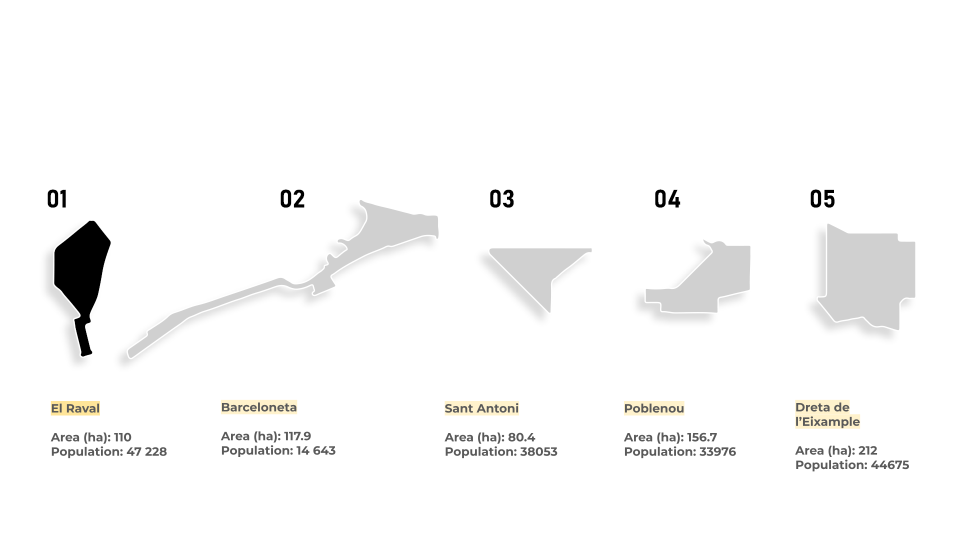

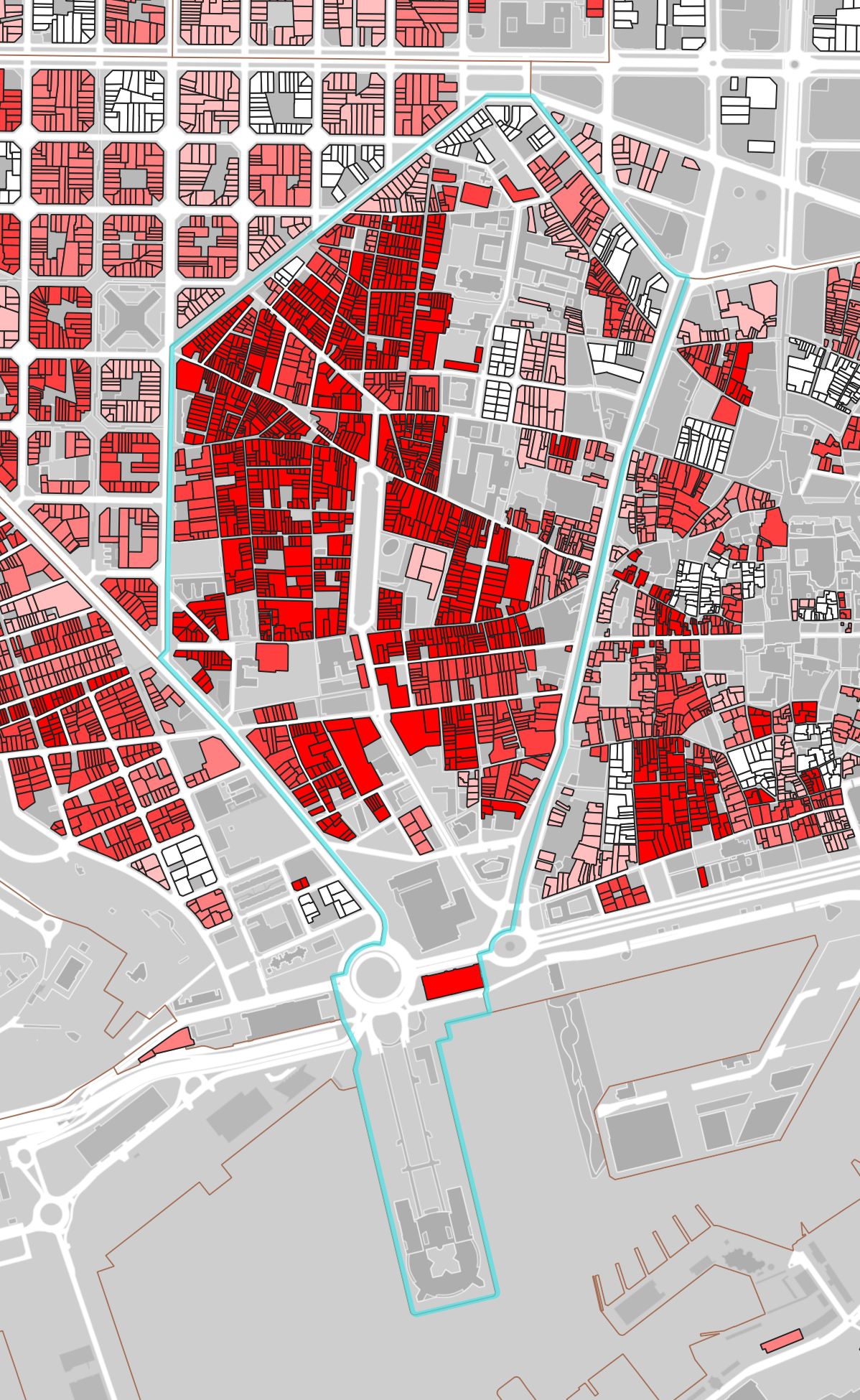

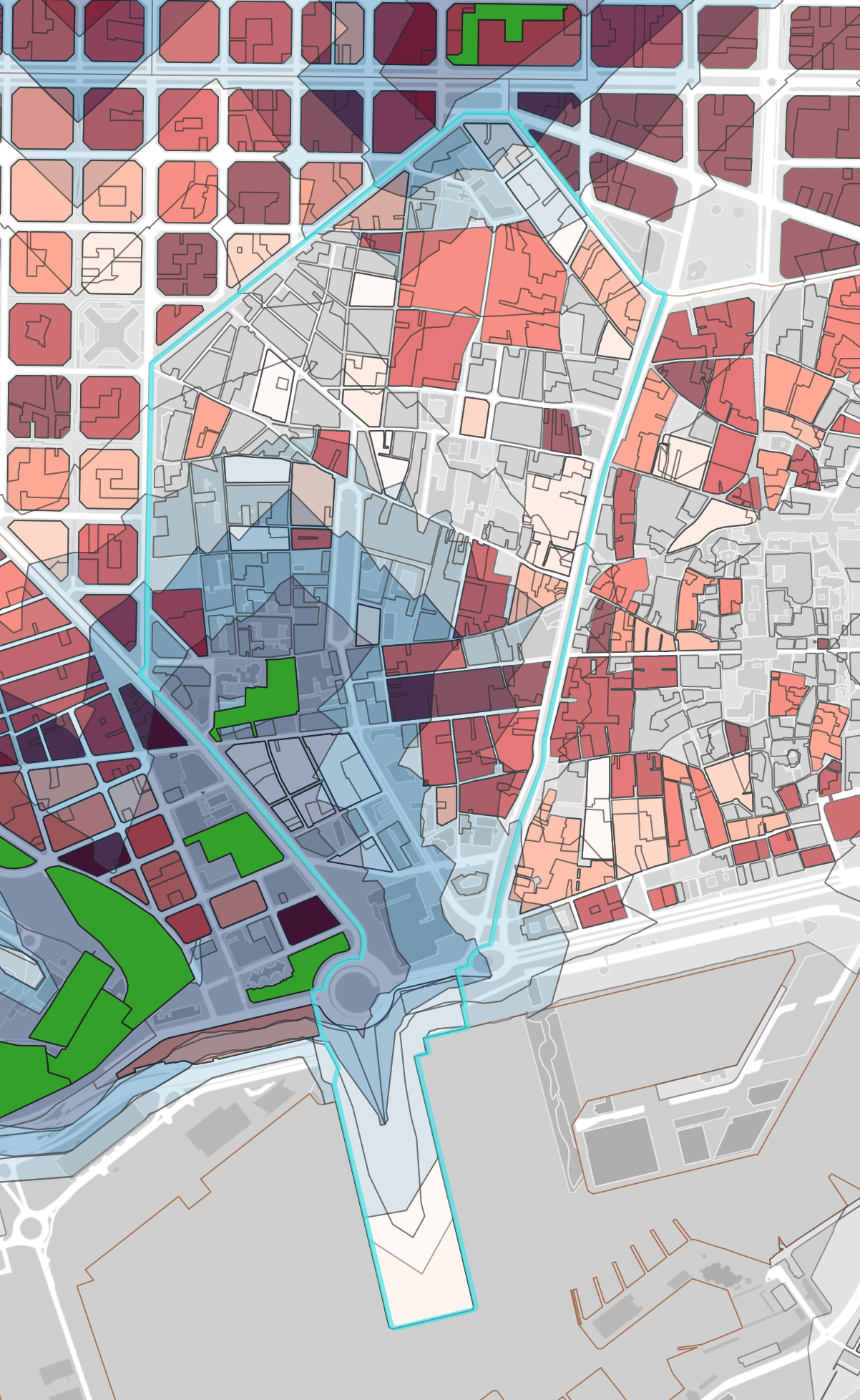

Based on our analysis of socioeconomic conditions in the neighborhood, as well as the density of residents and tourist lodgings alike, these initiatives will offer a welcome relief for residents. El Raval is one of the densest neighborhoods of Barcelona, with 429 residents per hectare. Despite its density, it also has high numbers of tourism housing units in the city. In September of 2022, it had 1216 Airbnb listings, second most of all neighborhoods in Barcelona (ArcGIS Barcelona Airbnb Price 2022 Map). A map of data on tourist housing units (HUTs) shows high densities of these in various portions of El Raval. While El Raval does not have the highest population density and has various levels of HUT density throughout, our map of risk of housing exclusion shows that residents are already in a precarious situation that are further impacted by HUTs. This is further supported by a study of socioeconomic vulnerability across Barcelona, where El Raval stands out as one of the neighborhoods with the highest index.

Given these realities, other policies we encountered had a direct focus on the residents in El Raval. Prometheus, a scholarship program piloted in El Raval, allows public school students to pursue higher education. El Raval residents constitute the highest users of various other Barcelona Neighborhood initiatives, like free childcare, XARSE (a network to reduce barriers between city bureaucracy and residents), and Tast d’Oficis (a labor training and social integration project for young people) (Barcelona Neighborhood Plan). The Barcelona Green Deal focuses on economic challenges in the city, and proposes Via Laietana to foster innovation and attract talent in Ciutat Vella and the BCN Safe City-Safe project, an online advisory service for any business linked to the visitor economy (Barcelona Green Deal).

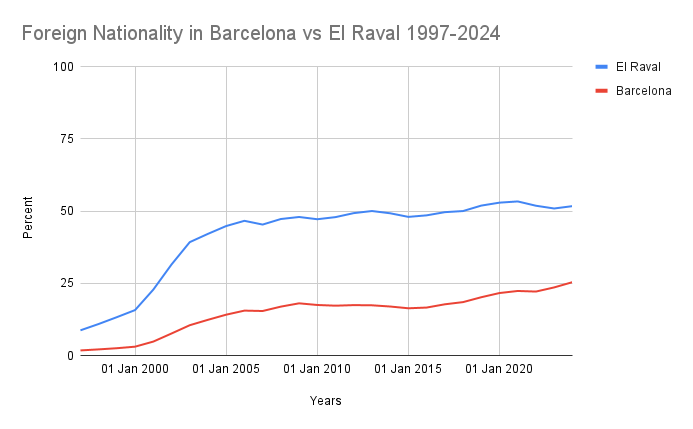

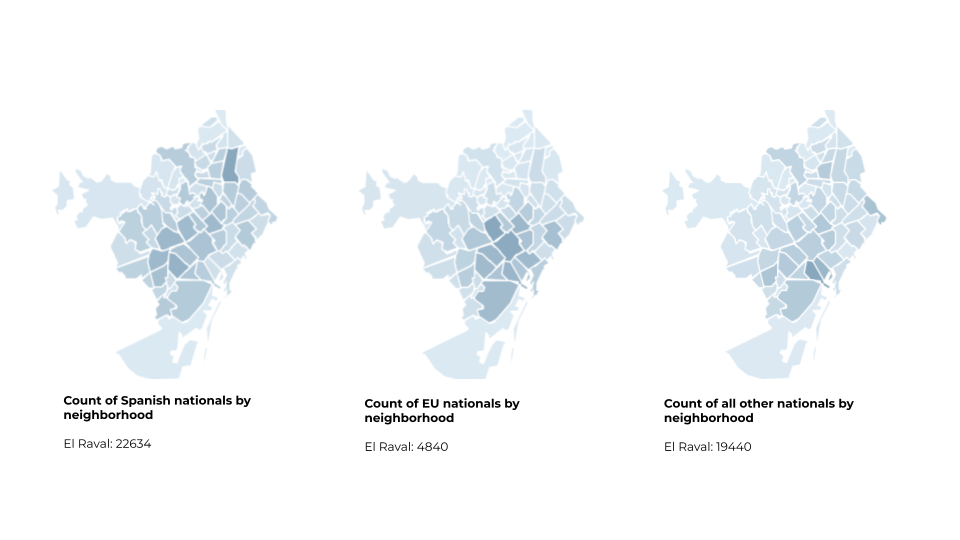

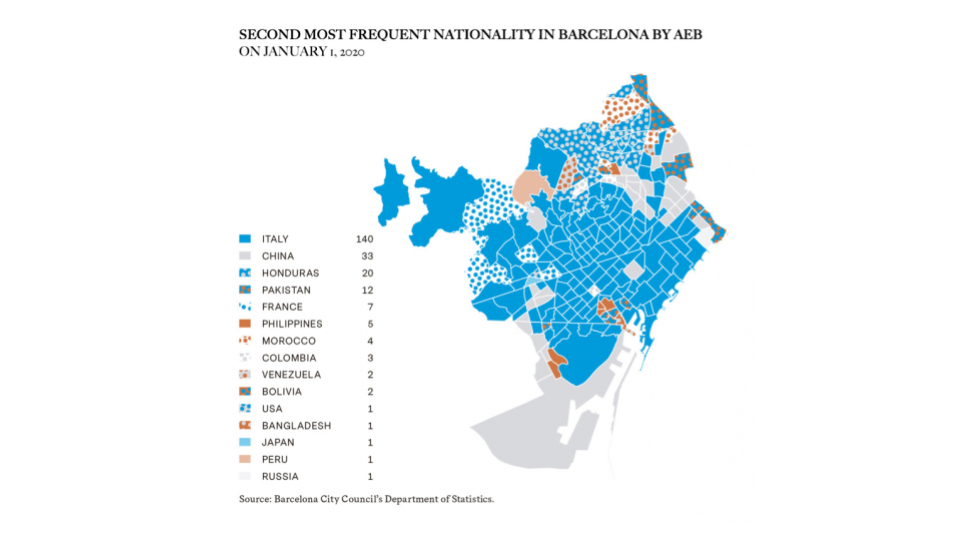

In a neighborhood as ethnically diverse as El Raval, these strategies serve as an important bridge linking immigrants to social infrastructure and economic opportunities. These resources are particularly important as we see that not only the proportion of foreign residents in Barcelona as a whole has increased over the past two decades, but in El Raval foreign residents now constitute over half of all residents. In El Raval, more immigrants hail from more countries outside the EU than in any other neighborhood in the City. In particular, the most frequent countries of birth among residents in El Raval include Pakistan, Italy, Bangladesh, and the Philippines.

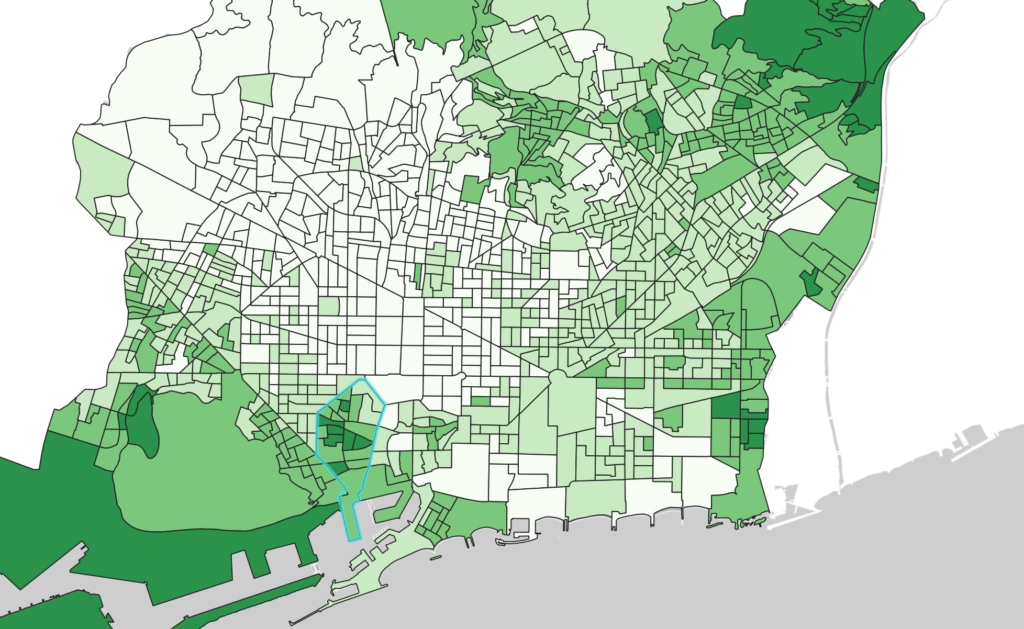

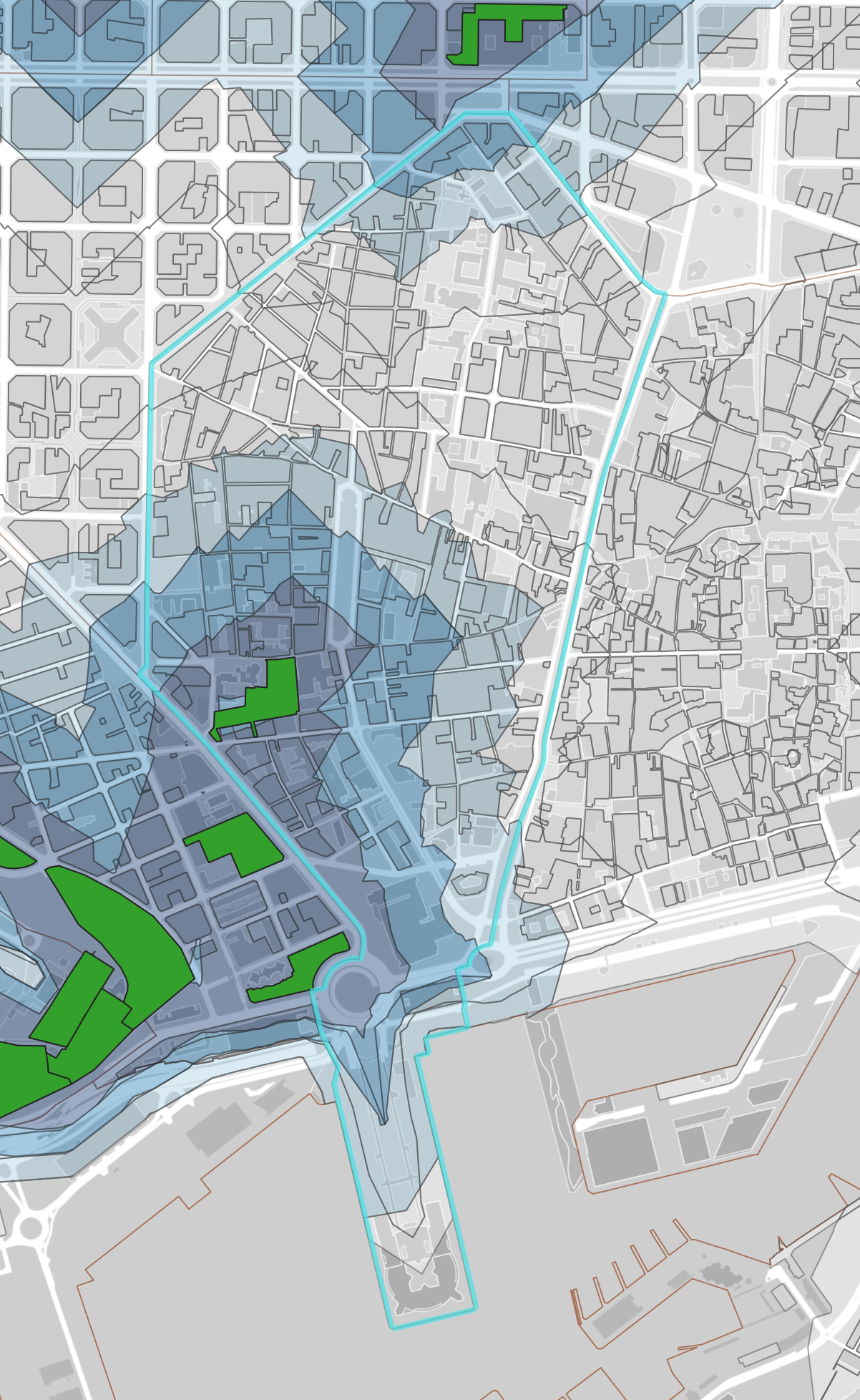

The fact that El Raval is simultaneously a destination for residents and visitors from all over the world poses interesting questions about how these groups, with different priorities and resources, share space. We explored this question through looking at access to green space for vulnerable groups (children under age 4 or adults 75 or older) in El Raval. Our first observation was that approximately half of the area of El Raval does not have decent access to a green space, and that there is only one green space over 0.5 ha in size. When we overlaid the density of HUT units onto this access to green space map, we found that the highest concentration of HUTs have the best access to green spaces. Thanks to the Special Urban Development Plan for Tourist Accommodation (PEUAT), no more HUTs will be added in areas where the highest density of tourist accommodation establishments are found, including El Raval. Additionally, when an accommodation is closed in El Raval, a new one may only be opened in another zone of the city (PEUAT https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/pla-allotjaments-turistics/en).

Efforts like the PEUAT renegotiate the city’s priorities and make important commitments to residents. They also leave us with some important questions. In a small neighborhood like El Raval, is access to green space a zero-sum game? Must access to city offerings for some come at the expense of others? As the city of Barcelona implements new initiatives in the neighborhood, residents take advantage of increased opportunities, and the tourism industry rethinks methods of engaging visitors, will residents and visitors be able to share space in mutually beneficial ways?

One hopeful and promising idea we came across was proposed in “Visitors and Residents in El Raval Neighborhood of Barcelona. New Opportunities for Creative Tourism?” which explored the perceptions of residents and visitors mentioned earlier. The researchers identified the potential of digital tools to connect visitors and residents by “foregrounding a cross-cultural element would promote co-creation of sociocultural value by allowing residents and visitors to share their own stories, and create new ones together” (p15, Visitors and Residents in El Raval Neighborhood of Barcelona).

We also found successful spatial interventions that catered to residents and visitors alike. In the study Urban Development And Preserving Place Identity As A Result Of Effective Revitalisation Of Barcelona’s El Raval District, researchers explored the impacts of the construction of new cultural buildings in El Raval, like MACBA and CCCB. They noted, “El Raval’s revitalization was effective, while preserving its cultural heritage and leaving indigenous habitants. [The] main result of this renewal was pronounced economic growth, maintaining a distinctive identity and a relatively low level of gentrification” (p170, Urban Development And Preserving Place Identity As A Result Of Effective Revitalisation Of Barcelona’s El Raval District).

El Raval’s evolution from an industrial hub to a vibrant multicultural neighborhood highlights the intricate balance between historical preservation, resident needs, and the pressures of tourism and urban development. This transformation reflects the area’s rich cultural heritage while facing socio economic challenges such as overcrowding, rising rental prices, and strained local resources. This situation raises essential questions: Who has the right to define El Raval’s identity—long-term residents with deep ties to the community, or the influx of tourists and businesses that shape its landscape? What level of authority should the government hold in guiding development, and to what extent should local residents influence decision-making processes?

As initiatives like the PEUAT and tourism decentralization are implemented, it is crucial to evaluate whether these strategies will genuinely prioritize resident well-being and cultural preservation or further exacerbate existing issues. The neighborhood’s future will depend on successfully balancing the needs of residents with the demands of tourism, ensuring that El Raval remains a space for rich cultural exchange and community resilience.