Framing the Dilemma: Access vs. Autonomy

The Promise of AI for Inclusive Learning

Artificial intelligence (AI) is starting to gain traction as a tool to bridge educational gaps for people with disabilities. AI-powered learning assistants – from chatbots to adaptive tutoring systems – have emerged as a promising solution to provide personalized support at scale to the more than 240 disable people globally.[3] If AI learning assistants are designed with accessibility and personalization in mind, then they can significantly empower individuals with disabilities by enhancing autonomy and academic success. However, if these tools are developed using standardized, one-size-fits-all models, they risk reinforcing systemic barriers and excluding the very users they aim to support.

Empowerment: Enhancing Independence for Disabled Learners

AI learning assistants have the potential to significantly empower individuals with disabilities by removing barriers to communication, comprehension, and digital interaction. These tools are designed to adapt content and interface to the user’s needs, making education and information more accessible.

For example, AI systems such as Microsoft’s Seeing AI enable blind users to understand their environment by converting visual data into descriptive speech, while speech recognition assistants support users with limited mobility in operating devices or inputting text verbally [1]. Additionally, text-to-speech generators and predictive communication tools offer non-verbal users a functional voice, greatly enhancing their ability to participate in educational or social contexts [1].

A notable case of personalized support is Microsoft’s Immersive Reader, which adapts on-screen text display and auditory feedback for users with dyslexia or low vision [1]. Furthermore, AI-based tutoring programs adjust the difficulty or presentation of material in real time, helping students keep pace with content regardless of their processing style [1].

Evidence of these benefits is further supported by research showing that generative speech models have reduced word error rates by approximately 26% for individuals with atypical speech, significantly improving the usability of speech-to-text interfaces [2]. Similarly, AI tools that summarize and restructure web content have proven effective for dyslexic users, who benefit from simplified, decluttered information [2].

In light of these examples, it becomes evident that AI learning assistants can serve as powerful enablers of autonomy. By customizing content delivery and bridging communication gaps, they not only enhance access but actively promote independent learning and educational participation for disabled users. This aligns with the broader objective of inclusive design, affirming that when implemented thoughtfully, AI can transform the educational experience for those who have historically faced significant accessibility barriers.

Current Solutions

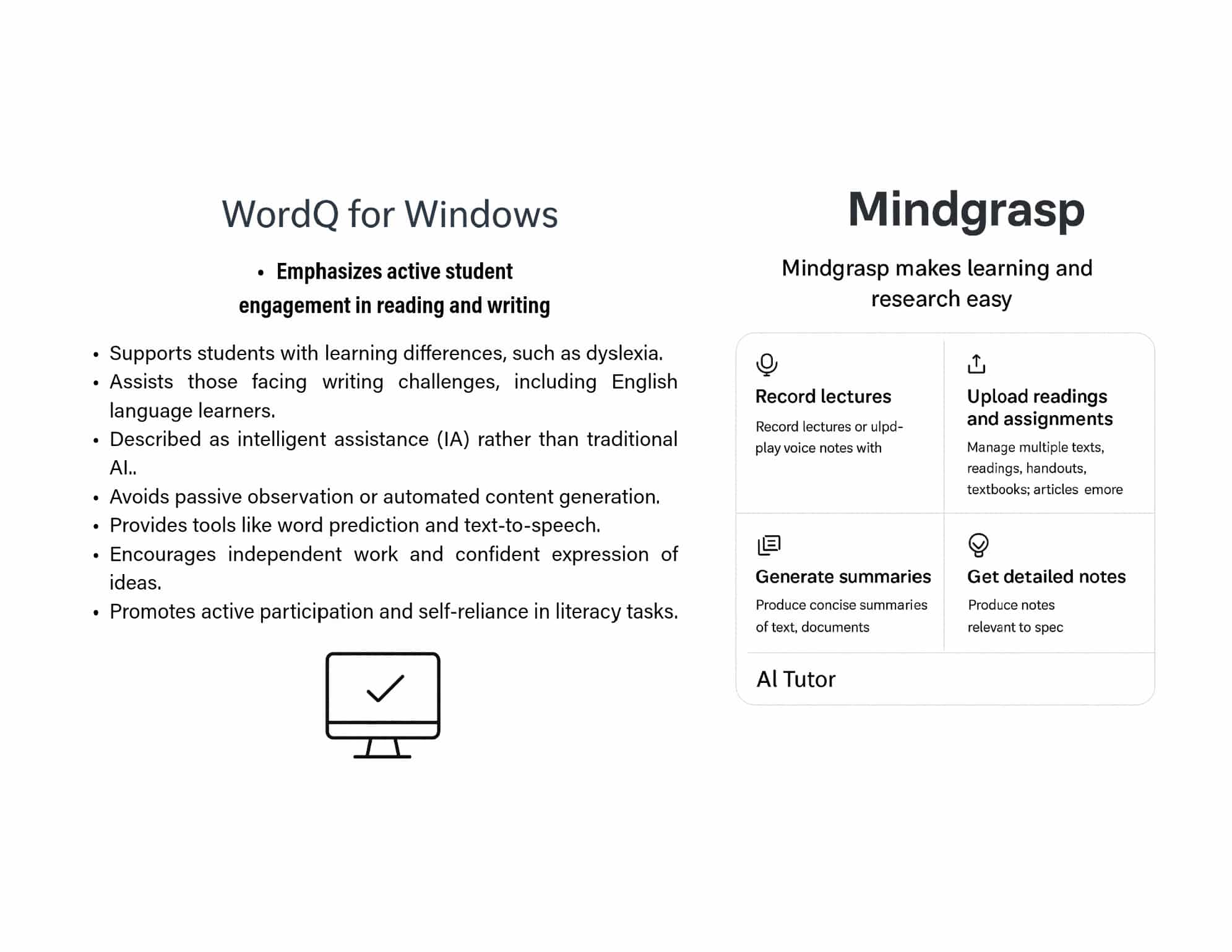

Current Technology Examples

The Standardization Trap: What Can Go Wrong

While AI learning assistants promise to make education more inclusive, they also pose critical risks when designed without attention to diversity in disability needs. A central concern is that many systems rely on a “one-size-fits-all” approach, overlooking the diverse accommodations required by students with disabilities. As a result, tools developed for a generic user profile often fail to support those who process information differently, leading to mismatches in learning experience [4].

For instance, when automated grading systems evaluate only rigidly formatted answers, students with dyslexia, autism, or cognitive disabilities may be penalized for responding in alternative ways—even if their content is correct [4]. This reveals a systemic flaw: instead of enabling access, AI can reinforce existing educational barriers when it lacks disability-aware design [4].

Additionally, the accuracy and sensitivity of AI outputs remain problematic. A study from the University of Washington showed that when an individual with an intellectual disability used an AI to summarize a document, the summary introduced factual errors and lost context [5]. Similarly, an autistic user who relied on AI to draft emails found that recipients described the tone as robotic and unnatural, misrepresenting the user’s intended message [5]. These examples highlight that AI systems lack the nuanced understanding needed to communicate authentically on behalf of users with unique communication styles.

Beyond technical concerns, there are also ethical and developmental risks. Educators worry that overreliance on AI tools like chatbots and text-to-speech may undermine cognitive development, especially in areas such as critical thinking and writing [6]. One dyslexia specialist noted that while these tools are useful, they can foster dependency and discourage students from building independent problem-solving skills [6]. Another expert expressed concern that students using AI like ChatGPT may outsource thinking, leading to shallow learning and even plagiarism [6].

A deeper issue lies in the systemic biases embedded in AI systems. If people with disabilities are underrepresented in training data—a frequent occurrence—these tools tend to perform poorly for them. For example, speech recognition often fails to understand atypical speech, rendering such tools unreliable for many disabled users [4]. Moreover, development teams may deprioritize accessibility based on the flawed assumption that the disabled user base is too small to matter, further entrenching ableist design norms [4].

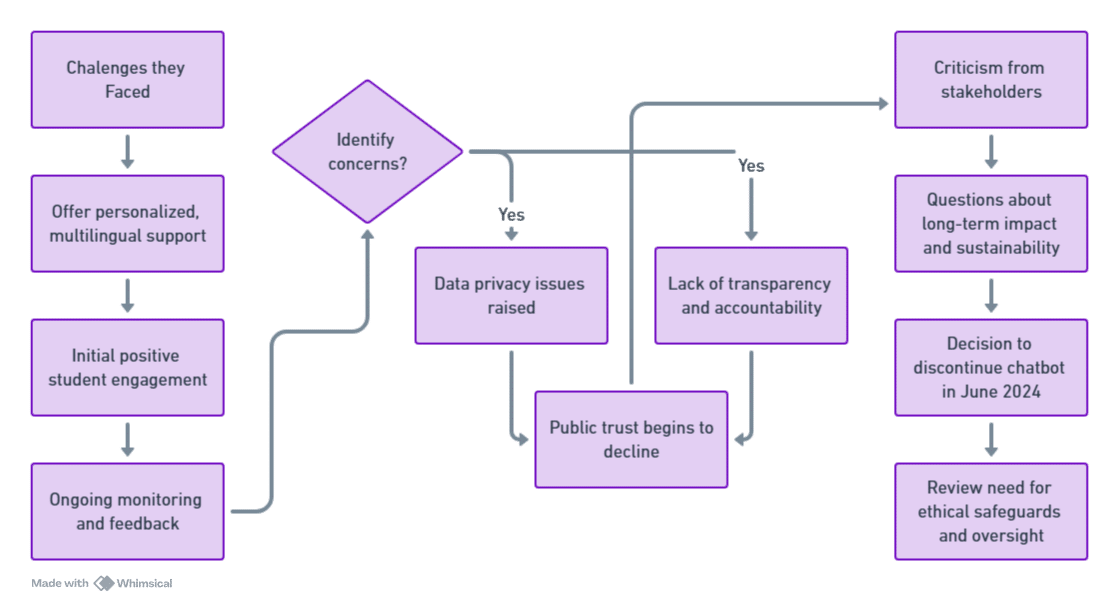

Case Study: Testing AI Tools in the Real World

Idea: Customized AI chatbots can enhance educational engagement and accessibility for students when tailored to individual needs.

Example Supporting the Idea:

The Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), in collaboration with All Here Education, launched the chatbot Ed in March 2024 to serve as an academic assistant within the Individual Acceleration Plan (IAP). Eligible students used it to receive personalized guidance in over 100 languages, track grades/attendance, translate information, and get reminders—supporting non-native English speakers and monitoring student progress [7].

Example Showing Limitations:

Despite early positive engagement, Ed was discontinued in June 2024 due to data-privacy concerns and questions about its long-term impact. Critics noted that the system lacked transparency and accountability, raising doubts about its sustainability and alignment with student needs [7].

This case indicates that while AI tools like Ed can enhance individualized support—through multilingual interaction, academic reminders, and real-time reporting—they also highlight important governance challenges. Without strong data safeguards and oversight, such systems risk undermining student trust and program viability, illustrating that empowerment through AI depends on ethical and transparent implementation.

Ethical Imperatives and Design Principles

Ethical Imperatives and Design Principles: Accessibility by Design in AI Learning Tools

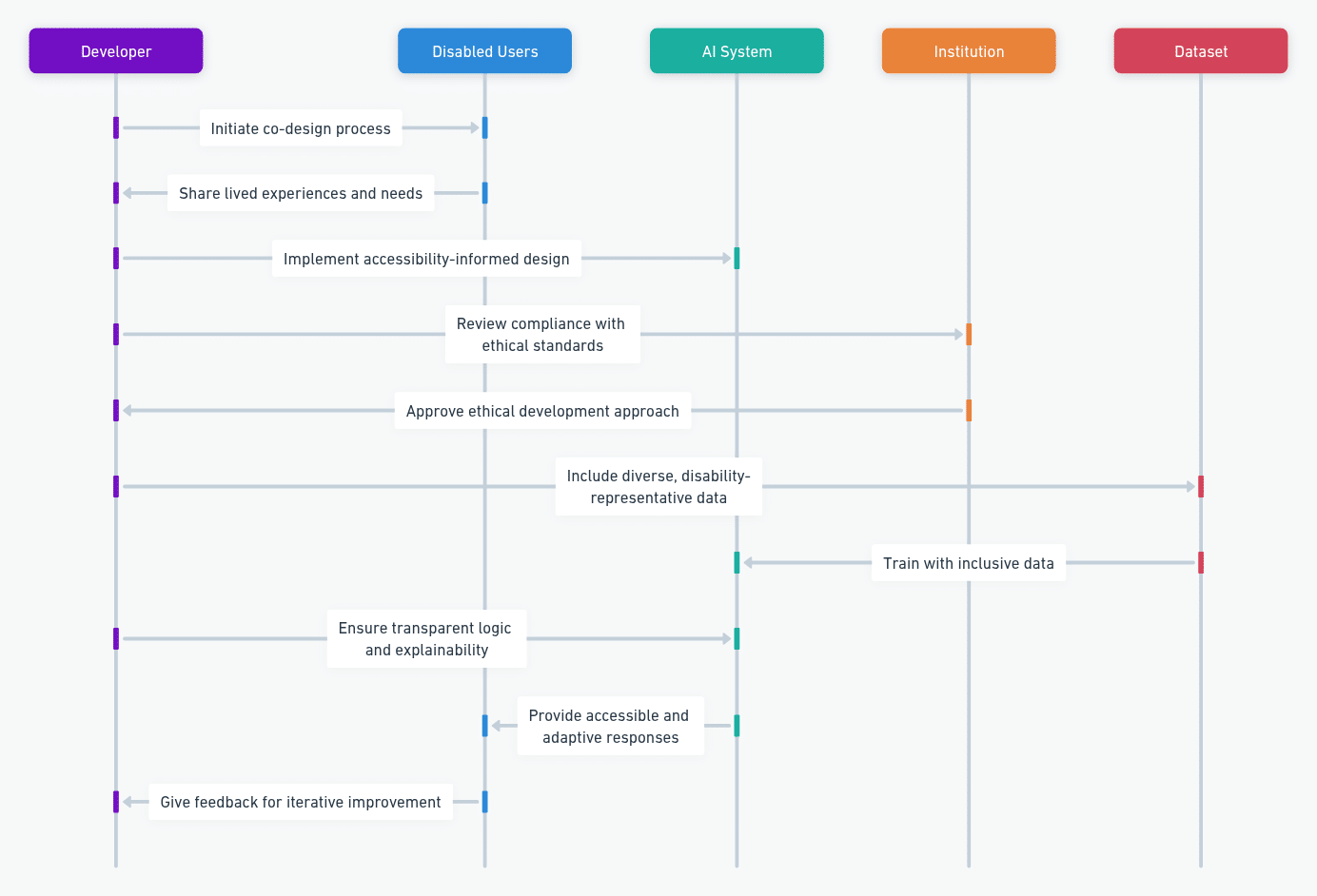

Idea: Ethical AI development for disabled learners requires participatory design, transparency, and inclusive data practices to ensure empowerment rather than exclusion.

Example Supporting the Idea:

Inclusive Co-Design: “Nothing about us without us” [14] is not just a slogan, but a design imperative. Involving people with disabilities in the design and development of AI tools – co-design – leads to more useful, intuitive solutions and enhances users’ sense of agency. [15]

An ethical approach begins by involving people with disabilities in the design and evaluation process of AI tools. For instance, the UK’s Open University collaborated directly with disabled students to co-design an AI chatbot for managing accommodation requests, ensuring that the tool responded to real-world accessibility needs [8]. This participatory model helps avoid assumptions and replaces standardized solutions with user-informed design, affirming the principle of building with, not for, disabled communities.

Example Highlighting the Ethical Risk of Neglect:

Conversely, excluding disability-specific needs during AI development can embed bias. Experts warn that training AI only on “clean” data that lacks atypical communication patterns, sensory inputs, or assistive device interactions excludes disabled users by default [9]. This leads to tools that do not function properly for the people most in need. Ethical practice demands that training datasets reflect diverse human realities, or else accessibility becomes an afterthought rather than a foundation.

As these examples illustrate, the ethical success of AI learning assistants depends on intentional inclusivity. By embedding ethical principles—such as co-creation, data diversity, and transparency—into every stage of development, AI can evolve into a tool that genuinely supports autonomy and dignity for disabled learners. This requires active collaboration among developers, institutions, and users, alongside adherence to international standards like WCAG and UNESCO’s AI ethics frameworks [10]. If done right, future AI tools may offer even more personalized, multimodal learning environments—but only if equity is treated as a design requirement, not an optional feature.

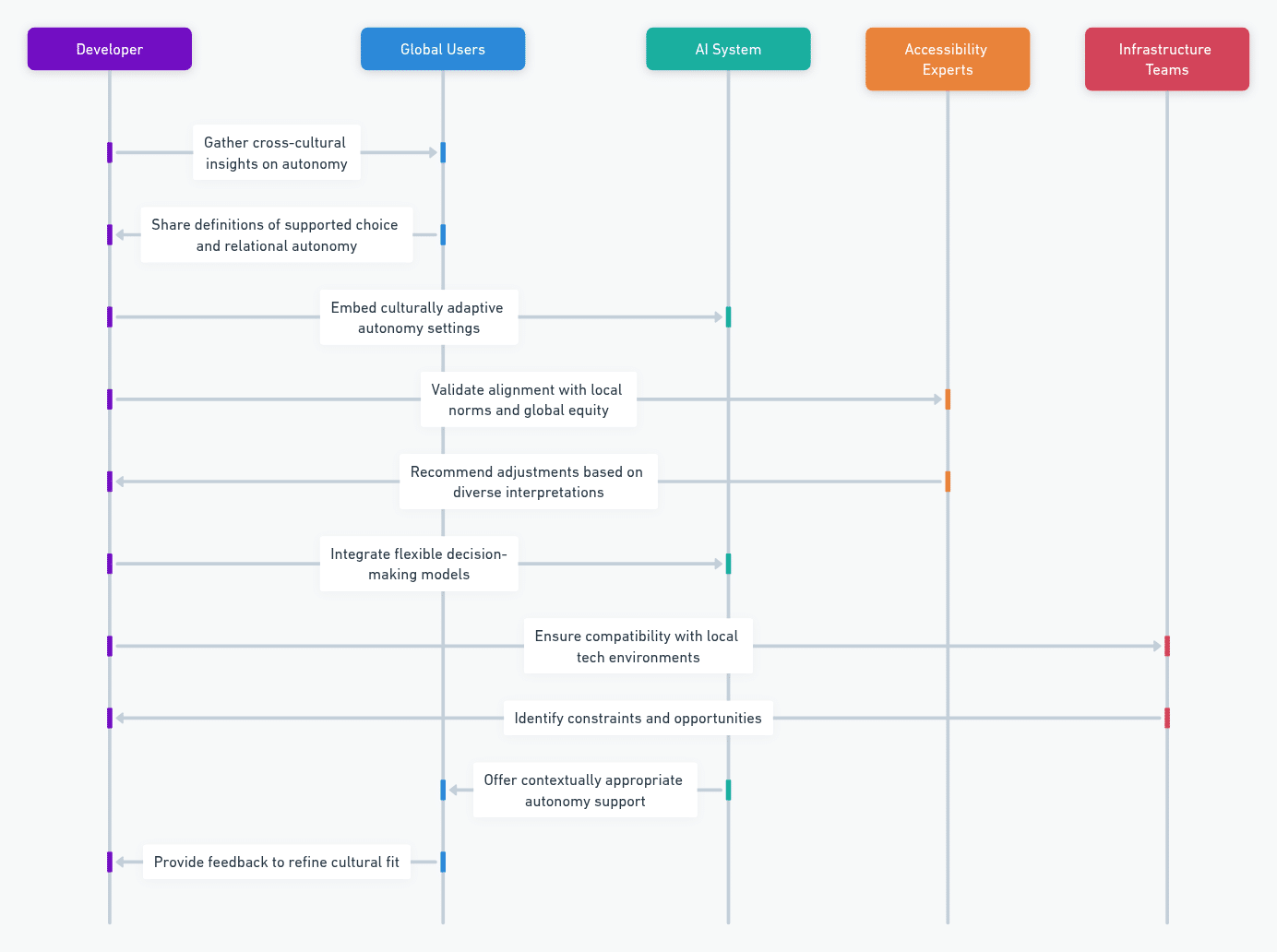

Beyond Tools: Power, Culture, and Global Gaps

Idea: Autonomy in AI learning systems must be context-aware and culturally sensitive. Empowerment is not universal—it depends on how AI balances guidance with user control across diverse social, cultural, and global contexts.

Example Supporting the Idea:

A cross-cultural study published in Applied Psychology examined the perspectives of disabled individuals and caregivers from four continents. The research revealed that autonomy is often understood as “supported choice within trusted relationships” rather than absolute independence. In many non-Western contexts, relational autonomy—grounded in community and shared decision-making—is preferred. Thus, AI systems designed with rigid Western notions of autonomy may misalign with user expectations, particularly in cultures that value collective agency [11].

Example Highlighting Ethical and Global Design Gaps:

This perspective complements findings from a Saudi university study, which used Self-Determination Theory to examine the impact of AI assistants on student motivation and creativity. The study concluded that autonomy-supportive design significantly enhances learner outcomes—but only when it allows users to choose how and when to engage with the AI, rather than being guided too forcefully [12]. However, global inequalities in infrastructure, language access, and internet bandwidth mean that such AI systems may not function well—or at all—in under-resourced regions, thus reinforcing digital exclusion [11].

Together, these cases emphasize that AI autonomy must be responsive to both personal and cultural dimensions of empowerme. Autonomy-enhancing tools should not be one-size-fits-all. Ethically designed AI must flex to user values—whether that means reinforcing individual independence or enabling guided choice within relational contexts. Without attention to power dynamics, cultural variation, and global access gaps, AI risks undermining the very users it aims to support.

Conclusions

AI learning assistants hold transformative promise for disabled learners—but only if developed through an accessibility-first and ethically grounded approach. These tools have the potential to deliver unprecedented levels of personalized learning, independence, and support. When designed with inclusive intent, they can adapt to the diverse needs of users, significantly enhancing access to education and communication [13]. However, if AI is developed using biased datasets or based on rigid assumptions about user behavior, it risks replicating existing systemic inequities. This could result in a standardized and impersonal learning experience that marginalizes the very communities the technology is intended to support [13].

As global research highlights, the future of inclusive AI is not fixed; rather, it is a collective responsibility shaped by the coordinated efforts of educators, technologists, policymakers, and disabled individuals. When these groups collaborate meaningfully, AI can serve as a platform where technological innovation and human diversity intersect to expand equitable learning opportunities [13]. Realizing this vision requires ongoing commitment to design justice, cultural sensitivity, and participatory development practices—ensuring that core values like autonomy, guidance, and user choice are integrated from the start.

Ultimately, the true impact of AI in inclusive education will be determined not by its technical sophistication alone, but by the ethical and human-centered values embedded in its design. With intentionality and equity as guiding principles, AI can become a powerful enabler of inclusion. Without them, it risks reinforcing the very barriers it seeks to remove. The imperative is clear: AI must be shaped into a tool that empowers every learner to thrive, especially those who have historically been left out.

Resources

[1] Neuronav.org. “How AI Enhances Accessibility for People with Disabilities.”

[2] GovTech.com. “AI Helps Reduce Speech Errors, Supports Dyslexic Readers.”

[3] Inclusive Education with AI: Supporting Special Needs and Tackling Language Barriers

[4] EveryLearnerEverywhere.org. “AI in Higher Ed: Opportunities and Risks for Disability Inclusion.”

[5] GovTech.com. “Disabled Students Struggle with AI Tools Designed to Help.

[6] BusinessInsider.com. “Experts Warn AI May Harm Learning for Students Who Rely on It Too Much.”

[8] Blogs.Microsoft.com. “The Open University AI Chatbot Accessibility Collaboration.”

[9] GovTech.com. “Inclusion Requires Disability-Aware AI Datasets.”

[10] EveryLearnerEverywhere.org. “Ethical Frameworks and Accessibility in AI for Education.”

[11] Walker, S., et al. (2024). “The Voice of Persons with Disabilities in the Design of Autonomous AI.” Applied Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.1248

[12] Alqahtani, A., et al. (2024). “Impact of Intelligent Learning Assistants on Creativity.” Applied Artificial Intelligence in Education.

[13] arXiv.org. “AI in Inclusive Education: A Global Vision for Equitable Learning.”

[14]UN Enable – International Day of Disabled Persons, 2004 – United Nations, New York