Keep the water out!

It seems as though this is the first shard of wisdom one is exposed to when studying Architecture. I remember coming across this motto of sorts for the first time in a class on detailing; my professor seemed almost obsessed by the presence of water and its surreptitious ability to undo the most robust of building systems. Water seems to receive quite a lot of attention from the minds of builders – to good effect. The impermeability of our structures is a feature very few of us would be ungrateful for; however, the purpose of this body of writing is to challenge the popularity of water as the main fluid worthy of our awareness as architects and users, for we are in the eternal – yet all too overlooked – presence of yet another set of free flowing particles: Air.

Air is everywhere. It permeates all parts of the systems we call home, be it our bodies or our buildings. Air occupies the outsides and the insides of architecture, residing even in the skin that separates those two realms. Once made aware of the presence of air, one begins to perceive the built world as an amalgamation of parts, perpetually dissolving, intertwining, and reconnecting at the ethereal hands of the substance we breathe.

The sad truth about air is its invisibility. It can almost only be perceived through the distortions it causes to the things that we see. It is the vessel of our senses; however, air is very present and can be perceived a lot more than it may seem. It does not take much introspection to recall that all our senses have been touched by air. When we perceive heat and cold, we perceive the temperature of air. When we run or spin, we feel the travels of air through our fingers, hair and any of our parts exposed to it. When we smell petrichor, we experience the fragrance of air. When we have a conversation, we cannot hear people… In fact, we hear air.

Air and Computational Design Software

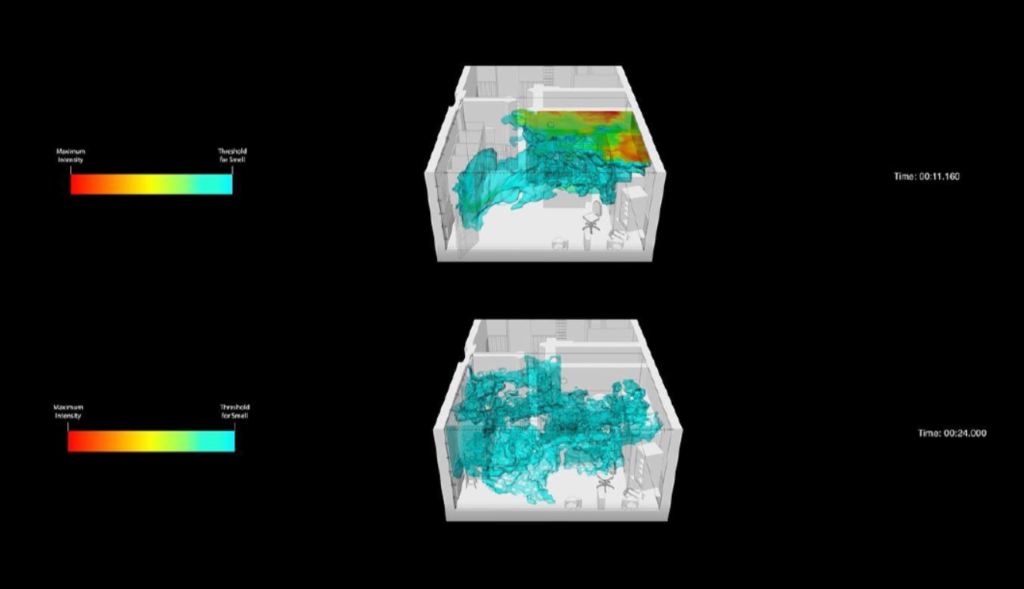

This brings to mind the work of forensic architecture, a group that uses design and simulation tools to investigate criminal occurrences. In many cases, they simulate the movement of air to reconstruct the memory of certain crimes in the minds of witnesses. They use simulations to make the invisible visible, somewhat building visual representations of a silent killer. One of their works that uses air to decrypt a crime quite well is the Murder of Halit Yozgat, in which the group uses air and the smells it carries with it to analyze the source and process of the murder in the eyes of witnesses. It is interesting to note here that we might believe that the contribution of a witness could be limited to the space he or she sees, bound by walls. In fact, it could be much more than that, as the movement of air transcends the boundaries of what we can see. It is fascinating to be able to reconstruct such an intense sequence of events through an understanding of how air moves. These simulations decrypt the mystery and let air guide us to the answer, but also make us realize how present air is in our built space. It indeed is everywhere, or rather, capable of transporting itself anywhere. This invisible fluidity amidst a seemingly static environment is one I have particular awareness of over the course of the past few months.

Air and Architecture

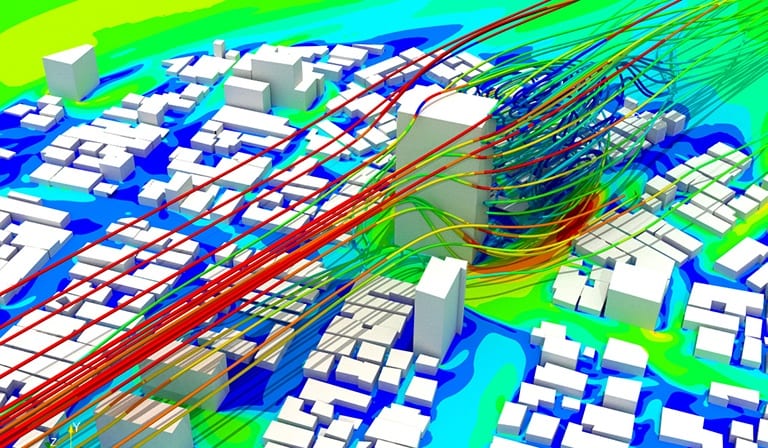

It is strange, almost disturbing to realize how incomplete our perception of built space is. If you look at an image of villa savoy, you only focus on the orthogonality of what you see… and a modernist’s eyes are satiated by it. The Cartesian simplicity of it is all that is noted, but it is an illusion we have almost settled for, a form of architectural denial. Be it an intrinsic determination to quantify and rationalize our surroundings, or a mere added attention to what is easier to perceive, we have blinded ourselves with the conviction of living in a static world… but the realm of solids bathes in one of fluids. The architecture we occupy is infused with swirls. After working with and trying to construct wind CFD simulations, I cannot but admit to the great impact air can have on our experiences of space.

We may then ask ourselves: how can architectural design elucidate the role of air in the built world?

We may begin tackling this question through an exploration of the relevance of air in our architectural environment, followed by an investigation of recent design ventures that place air at the heart of a design concept.

Air as Structural System

The impression we have given of air thus far has been that of a supple entity, softly meandering through space. However this gentle image is to be complemented by one of strength and robustness. Like all gases, air is a compressible substance, and with compression comes pressure. If we reflect on the concept of pressure, we are immediately drawn to the realization that air is the entity that supports us. We can literally build with air. The growing popularity of inflatable structures points to the fact that air can even be used as structure. The lightest, most invisible material can actually be used as a structural element. Those structures are completely transparent; they free us of our typical understanding of columns and beams.

We may find quite a few examples of such structures. Aether Architects are a group that have started experimenting with the use of air as structure with their work . Reflecting on the words of the architects and the intention of their project Air Mountain Pavilion below, we can point to the fact that they use air as a multidimensional element, exploiting the element to almost its full potential.

The geometry of the building, using the air interlayer as the structure of the building and to form the insulation layer, the inner top of the anti-surface to avoid the sound focus, the top orifice to form a hot air diversion and lateral open hole to form the airflow convection.

– Aether Architects

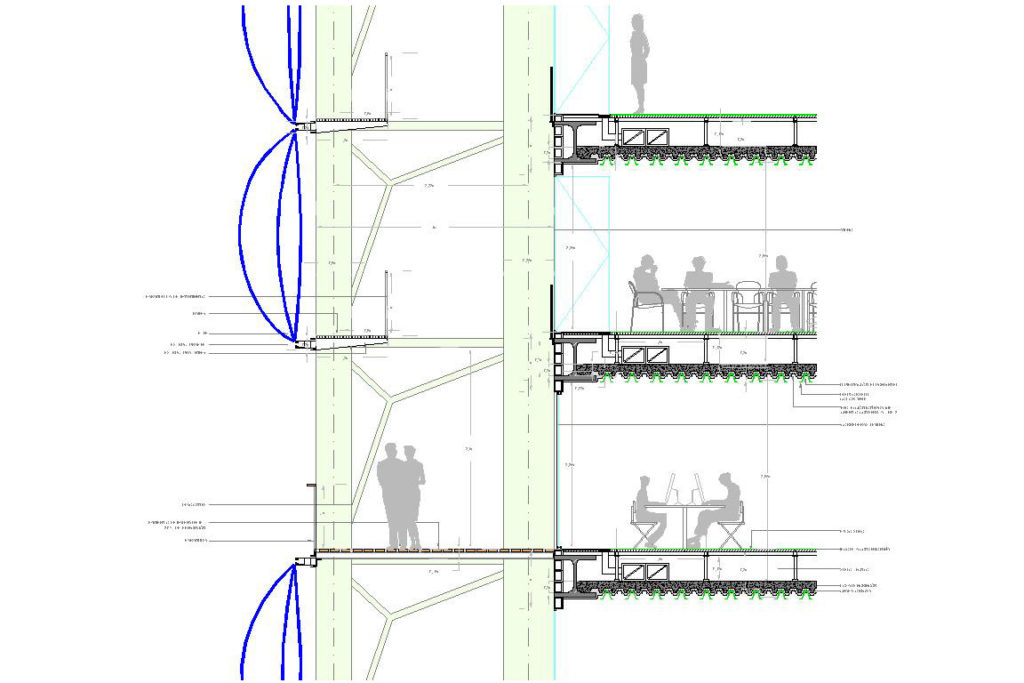

In his article titled Air Apparent: Pneumatic Structures, Will McLean details a series of projects that start to use air as a structural material. His discussion of ethylene tetra-fluoro ethylene (ETFE) membranes air filled pillows point of the efficacy and lightness of air as enclosure, and it brings me to think of the example of the Media TIC building in Barcelona by Enric Ruiz Geli. The use of the ETFE membranes on its facade enables the use of three layers of air as insulation and filtering solar radiation with an encapsulated cloud.

Moving more closely to structural elements, Luchsinger and Pedretti’s prototype of an air inflated “Tensairity” beam only further proves the potential of air as an important material in architecture, not only in terms of experience but also more pragmatic and as an efficient functioning structure.

Air as Water

Air can also be embodied as water – a visible element that characterizes an invisible entity. Yet another example of making things appear out of nothing is the example of Warka Water. Just like the previous example of a surface that is kept in place by an apparent nothingness, this project tries to ‘extract water out of thin air’. This tower is an inexpensive infrastructural element, built with elestic juncus stalks and nylon or polypropylene mesh, is meant to provide a village with clean drinking water that is typically not readily available to them.

What’s nice is that this structure elucidates the role of air in a sustainable future. However it is more than a distant reminder that air is there somewhere, like the cases of wind turbines that are isolated and far away from the people; people know that they are there but do not engage with them. Rather, this project is meant to engage directly with the people and exist at the heart of the community. What is great about the water membrane is that is becomes a reinterpretation of a communal watering hole, one where the air takes center stage since the water seems to appear out of nowhere.

Conclusion

Air is invisible, why we may assume it’s contribution is less substantial than it’s other, more tangible counterparts may just be that our senses do not do it enough justice. Or perhaps it is just because our sense have become so attuned to bright pops of color and the loud roars of our urban existence. It only takes a few moments of reflection to recollect how many times we have experienced air. Air may well be one of the most experiential versatile elements our bodies can possibly experience. Heat waves making the world dance and sway, snow swirls, tornados, a cool breeze. Air is ever changing and ever present. The purpose of this exploration is to be able to point our finger to the nothingness and see air. Through computation and understanding the complexity of air in all its components, air goes from being a nothingness to being a substance upon which our surroundings are transcribed and more sustainable dioramas of the built environment are conceived.