The Algorithmic Epoch

Modern advertising was born out of propaganda techniques developed in World War I by Edward Bernays. He realized that by manipulating symbols and emotions, it was possible to shape mass behaviour, a concept that now forms the backbone of our algorithm-driven economy. The Internet, once heralded as a tool for global connection, has become an infrastructure for mass manipulation.

Today, three corporations dominate the Western Internet: Amazon, Meta, Google 1. Their core business is attention. These companies have developed sophisticated artificial intelligence to predict and shape users: the algorithms. The algorithms were created to drive consumption, and have greatly influenced our throw away culture, over-consumption and have driven polarization in society. These systems personalize each user’s feed, creating individual sources of truth and fragmenting consensus reality. The consequences are vast, from the microtargeted manipulation of voters by Cambridge Analytica to the polarization of entire populations through algorithmic news feeds.

microtargeted manipulations

As artificial intelligence systems grow more powerful and ubiquitous, privacy laws lag behind, with political leaders either complicit or powerless to resist the advances of big tech2,3. The responsibility to resist has shifted from institutions to individuals, and now increasingly, to designers of the environment we inhabit.

Tailored content delivery has been shown to intensify social division4,5,6, while th rise of generative A.I. tools capable of fabricating realistic media at scale has ushered us into a post-truth era7,8,9 where ground truth is quick-sand and there is no consensus reality. In our new reality, fact is fluid and trust is eroded.

This condition mirrors the final years of the Soviet Union, when the State flooded newspapers with contradictory accounts, creating a climate of vranyo, where everyone knew they were being lied to, but no longer cared. George Orwell foresaw a different kind of dystopia, one in which history was actively rewritten and language itself was weaponized: “The past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became the truth”10. But unlike Orwell’s vision of a centralized Ministry of Truth, today’s distortions emerge from algorithmic systems that shape each person’s digital reality, quietly and invisibly. Hyper-personalized information streams powered by AI now reach into every internet-connected device, every pocket, every person11.

architectures of resistance in the a.i. age

If A.I. shapes how we think and behave, then architecture must consider how we resist. Architects, as spatial strategists, have a critical role in maintaining public space, political agency, and human dignity.

architects should rethink public spaces for direct political engagement12

While totalitarianism relies on enclosed spaces, it is in the commons that the public confronts oppressive governments. From the 2014 Hong Kong Umbrella Movement to the 2025 Los Angeles Riots, protesters have deployed spatial tactics to evade surveillance: burner phones, lasers, face coverings, QR-codes, and masked movement patterns13. But what if the architecture itself became a tool of subversion?

passive countermeasures: design against surveillance

Subtle interventions in built space can disrupt AI surveillance systems without relying on confrontation. These passive measures embed resistance into the environment:

- Labyrinthine Landscaping: Complex pathways and strategic plantings obstruct sight lines, providing cover from drones and CCTV.

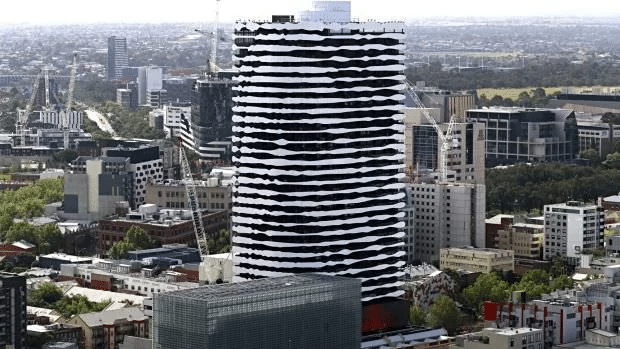

- Dazzle Cladding: Inspired by WWI naval camouflage, these high-contrast façades confuse computer vision. A contemporary evolution appears in the CV Dazzle project, which applies chaotic makeup and fashion to disrupt facial recognition.

- Adversarial Patterns: QR-style murals or pattern libraries designed to trigger false positives in machine vision systems.

- Faraday Skins: EM-shielded rooms, such as in microscopy labs, block radio frequencies and Wi-Fi signals, creating zones of digital silence.

- Reflective or IR-disruptive Surfaces: Strategic use of mirrored panels or coatings that scatter heat signatures and laser scans.

Each of these moves uses design to generate opacity, offering momentary autonomy in an age of hyper-visibility and connectivity.

Faraday Cages provide refuge from telecommunications..

Invented by Michael Faraday in 1835 passively block electromagnetic radiation rendering wi-fi and cellphones useless. Researchers working in electron microscopy labs tell of the quiet solitude and isolation from the modern world.

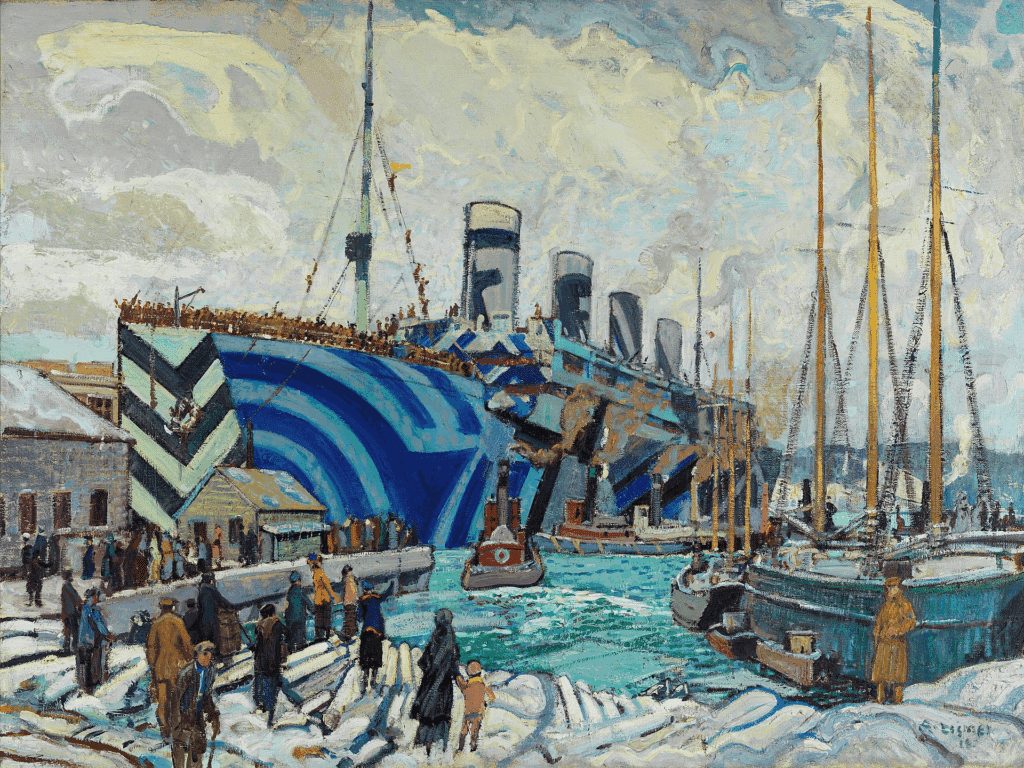

Dazzle camouflage from ships to faces to buildings.

The contrasting patterns used for Dazzle camoflage in World War 1 have been redeployed as hair and makeup techniques to thwart computer vision algorithms in the 21st Century, and used as a motif for architectural styling.

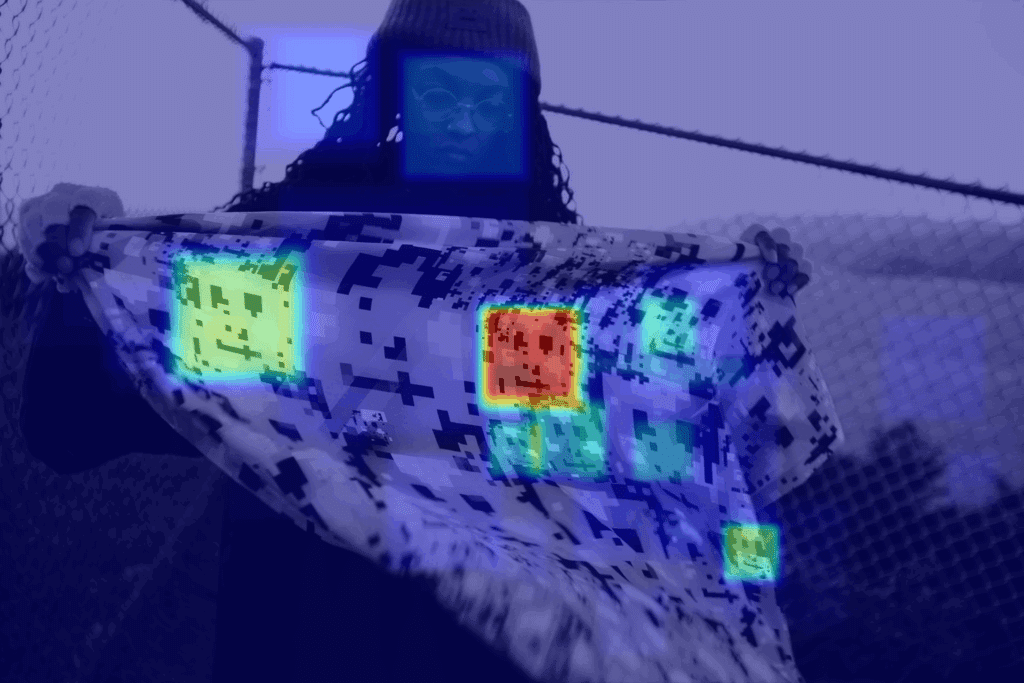

HyperFace demonstrates a false positive pattern that disrupts A.I. algorithms.

This method of producing false positives could similarly be used on facade elements to overwhelm and confuse surveillance A.I., parametric design can be used to incorporate these elements and validate them prior to production.

active resistance: spatial tactics for anonomy

But passive strategies are not enough. As surveillance systems become more adaptive, designers must explore active forms of spatial resistance that evolve alongside the technologies they oppose.

- Architectural Trojan Horses: Appear innocuous to humans, but hide adversarial patterns that disrupt algorithmic recognition systems.

- Tactical Structures: Deployable shelters, protest modules, and mobile canopies designed to block infrared, obscure drones, or scatter data signals.

- Dataset Poisoning by Design: Tools like Glaze or Nightshade allow artists to imperceptibly modify imagery so it pollutes generative AI training. Can buildings and urban spaces do the same, feeding architectural “noise” into LIDAR and mapping systems?

- Mesh Network Urbanism: Embedding decentralized, encrypted communications infrastructure into urban furniture or temporary pavilions.

- Reclaiming the Commons: Designing plazas, corridors, and interstitial spaces not for consumption but for assembly, disruption, and presence.

These interventions reclaim space not just physically, but politically, as sites of encounter and resistance.

beyond the Panopticon: a new spatial logic

The 20th century was defined by the well known Panopticon, a central eye, always watching14. But the 21st-century algorithmic eye is distributed, probabilistic, and non-human. It doesn’t need to see everything; it just needs enough data to guess what you’ll do next.

This shift demands a new architectural literacy, one that moves beyond transparency, beyond visibility. As designers of space, we must now ask:

Can we code for ambiguity? Can we simulate friction? Can we design for refusal?

Conclusion: toward an architecture of obfuscation

Computational design often pursues clarity, optimization, and control. But in the age of AI-driven manipulation, perhaps the most radical thing we can design is disorder.

The future of spatial resistance lies not in nostalgia or retreat, but in creative misuses of technology: hacks, disruptions, masks, noise. Not every building will resist. But some must.

“To build in the age of AI is not just to shape space, but to confuse the machine that reads it.”

references

- Zuboff, S. (2018). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs. ↩︎

- Solove, D. J. (2025). Artificial intelligence and privacy. Fla. L. Rev., 77, 1. ↩︎

- Manheim, K., & Kaplan, L. (2019). Artificial intelligence: Risks to privacy and democracy. Yale JL & Tech., 21, 106 ↩︎

- Burton, J. (2023). Algorithmic extremism? The securitization of artificial intelligence (AI) and its impact on radicalism, polarization and political violence. Technology in society, 75, 102262. ↩︎

- Park, H. W., & Park, S. (2024). The filter bubble generated by artificial intelligence algorithms and the network dynamics of collective polarization on YouTube: the case of South Korea. Asian Journal of Communication, 34(2), 195-212. ↩︎

- Ecker, P. A. (2025). Algorithms, Polarization, and the Digital Age: A Literature Review. The Digital Reinforcement of Bias and Belief: Understanding the Cognitive and Social Impact of Web-Based Information Processing, 21-43. ↩︎

- Moravčíková, E. (2020). Media manipulation and propaganda in the post-truth era. Media Literacy and Academic Research, 3(2), 23-37. ↩︎

- Lawrence, G. (2024). The Power to Lie: Propaganda and Post-truth Politics. In Societal Deception: Global Social Issues in Post-Truth Times (pp. 211-270). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. ↩︎

- Gorrell, G., Bakir, M. E., Roberts, I., Greenwood, M. A., Iavarone, B., & Bontcheva, K. (2019). Partisanship, propaganda and post-truth politics: Quantifying impact in online debate. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.01752. ↩︎

- Orwell, G. (1949). Nineteen Eighty-Four. Secker & Warburg. ↩︎

- Klincewicz, M., Alfano, M., & Fard, A. E. (2025). Slopaganda: The interaction between propaganda and generative AI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.01560. ↩︎

- Bobic, N., & Haghighi, F. (2024). Ecologies of resistance and alternative spatial practices. In The Routledge Handbook of Architecture, Urban Space and Politics, Volume II. Taylor & Francis. ↩︎

- Fussell S. (2019). Why Hong Kongers Are Toppling Lampposts. The Atlantic. ↩︎

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Vintage Books. ↩︎