We built an interactive kinetic pavilion that literally turns toward the light. At its heart the piece uses four light sensors (LDRs) arranged around a central mount and a single servo motor. The sensors constantly measure brightness from different directions; the motor then rotates the structure smoothly toward whichever sensor detects the strongest light. What looks simple on the surface a motor following a bright patch is actually a compact, intentional system that borrows behaviour from plants: the pavilion performs a mechanical form of heliotropism, a motion you see when flowers and leaves track the sun during the day.

The idea was to make something that feels alive without relying on complicated machinery or heavy computation. By using only four sensors and a proportional control strategy, the pavilion creates an organic, continuous motion rather than jerky or binary moves. When light shifts slowly across the site the pavilion rotates subtly; when a sharp beam or spotlight appears it leans quickly to face it. That interplay — slow, patient tracking and sudden reactive shifts gives the piece a presence that reads as deliberate and thoughtful, not mechanical.

Beyond the motion, the project is a study in scale and meaning. At small scale it can be a gallery sculpture: a tactile object that invites people to walk around it and see how the sensors respond to their shadows and flashlights. Scaled up, the same idea becomes an architectural prototype: a canopy that orients for daylight harvesting, a façade element that optimises shading and daylighting, or a climate-awareness installation that visualises changing sunlight patterns across a site. The simplicity of the hardware makes the concept versatile: it’s easy to prototype, low-cost to build, and transparent in operation — visitors can see the cause and effect.

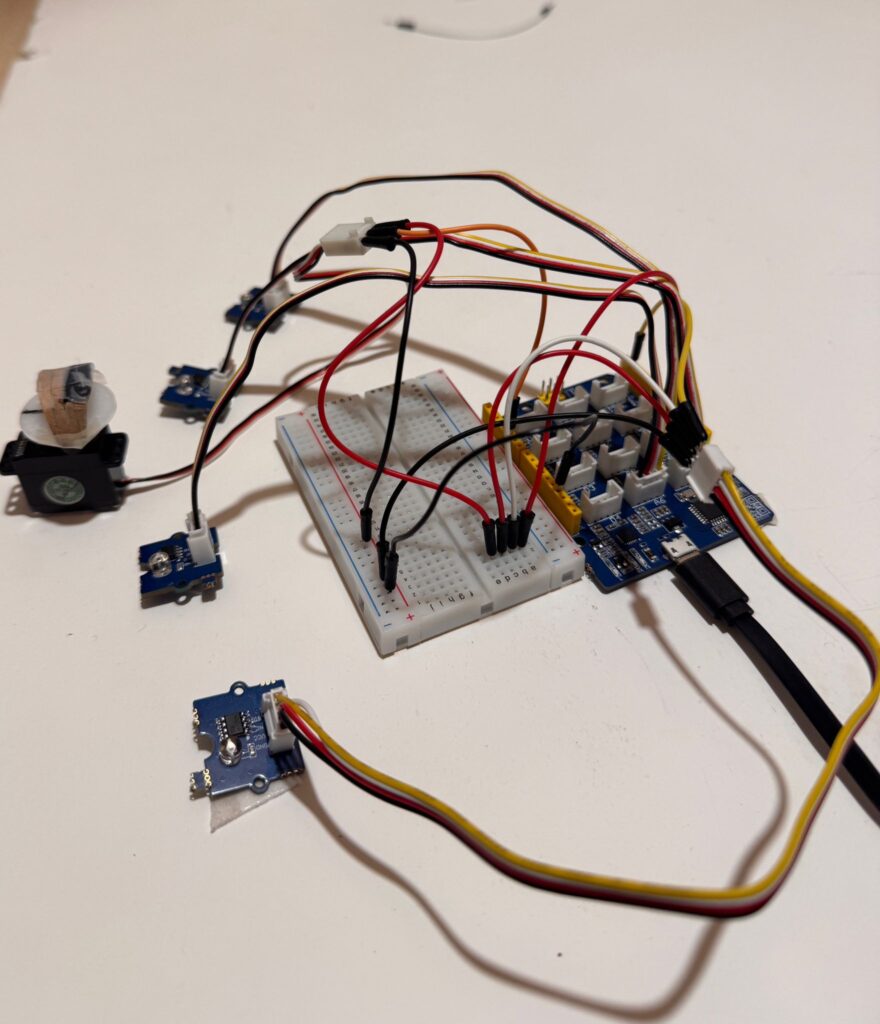

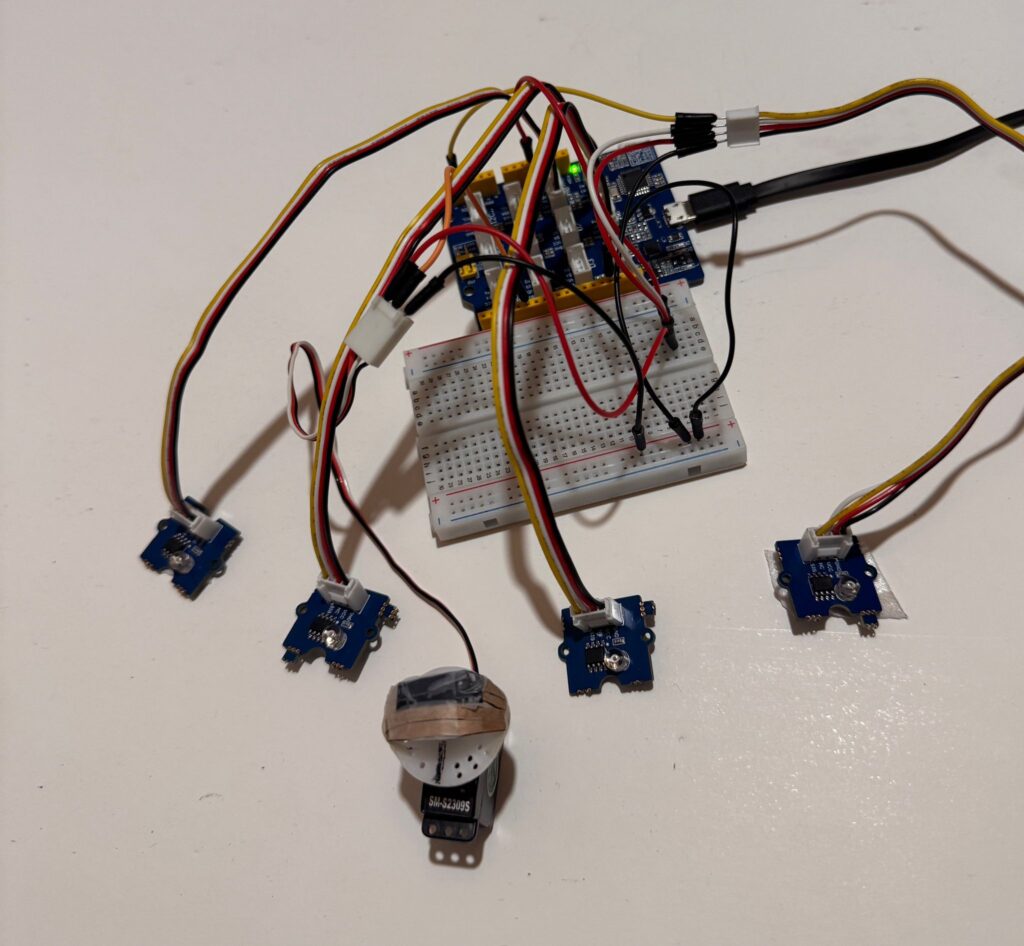

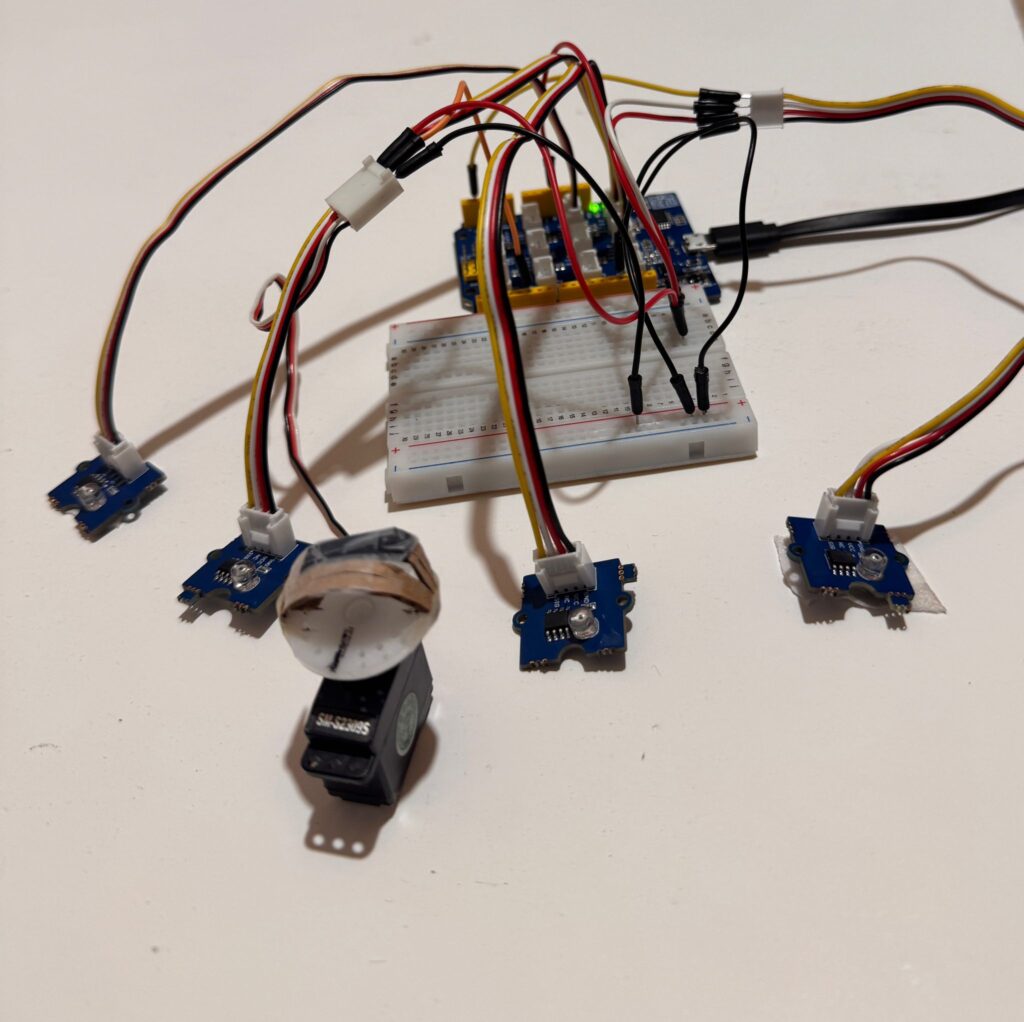

Technically, the system is straightforward. Four LDRs are mounted at 90° intervals around the rotating hub. Each sensor’s analog reading is read by a microcontroller. Those readings are normalized and compared to determine a directional bias. The servo receives a target angle calculated as a weighted average of all four sensor inputs, so the motion is proportional to relative brightness rather than simply switching to the brightest sensor. A small smoothing filter prevents jitter from small fluctuations and gives the rotation a gentle, plant-like pace. Power requirements are modest: a standard hobby servo and a microcontroller powered from a regulated 5V supply, with decoupling capacitors to keep motion noise from disturbing the sensor readings.

This project is not just about electronics; it’s about design thinking. It poses questions: what does it mean for architecture to be “attentive”? Can a built object exhibit simple, local intelligence that makes spaces feel friendlier or more aware? By translating a biological behaviour into a mechanical one, the pavilion becomes a teaching tool as much as an artwork it invites reflection on the boundaries between the animate and the engineered.

The system also offers clear opportunities for experimentation. You can tune the responsiveness: make it hyper-reactive for playful gallery pieces or slower and more deliberate for architectural installations. Sensors can be swapped for photodiodes to improve stability in bright conditions or scaled into an array for finer angular resolution. Different actuation systems stepper motors, linear actuators, or pneumatics let you explore variations in motion quality and scale. Finally, simple data logging can turn the installation into a visual record of a site’s changing light, useful for daylight analysis or environmental storytelling.

For fabrication and installation the pavilion is forgiving. The central hub can be laser-cut plywood or 3D-printed plastic; the LDR mounts are small tubes or brackets that keep the sensors flush to the exterior so they read unobstructed. The whole assembly can sit on a low pedestal or be integrated into a landscape setting. Because the electronics are compact and low-voltage, the piece can run off batteries or a small solar panel, making it suitable for temporary exhibits or remote sites.

In short: this pavilion is intentionally minimal in parts but rich in presence. It demonstrates how a handful of sensors and a single motor can create a convincing sense of life and agency. Whether used as an art object, a study in responsive façade systems, or a public demonstration about the sensitivity of natural systems to light, the project shows that expressive, climate-conscious design doesn’t always require complexity sometimes it only requires the right behaviour.