Case Study

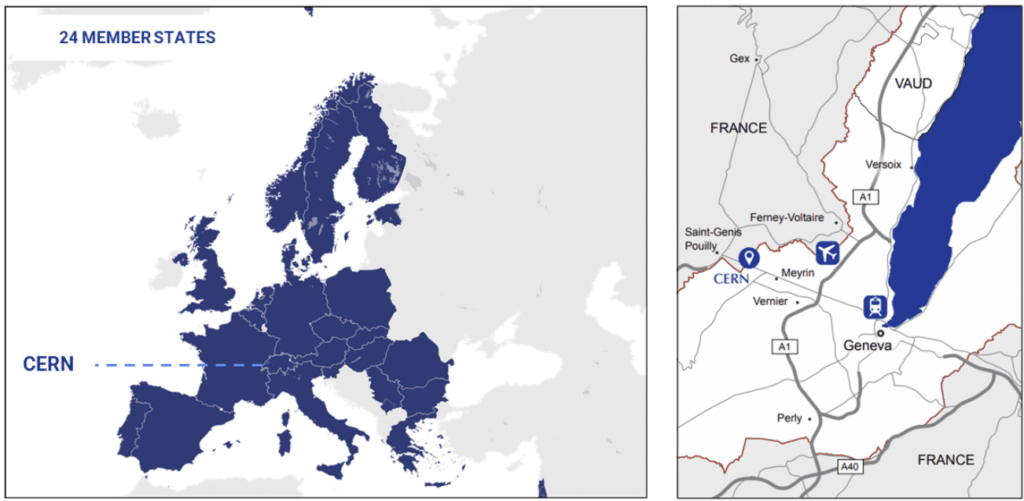

Site Context

The site is located at 46.2330, 6.0556 in Meyrin, Geneva, Switzerland. It includes the Esplanade des Particules, within the CERN campus, and covers an area of 45.000 sqm, surrounded by a urban residential area with low-rise buildings.

The primary land uses in the vicinity include grass and allotments. The site’s location within a major scientific research facility presents unique opportunities for innovative and sustainable design solutions.

Development goals

The goal is to transform the area into a cohesive urban core, while adding built space for the following activities:

- Hospitality, given the increasing number of visitors

- Residential, given the stable demand for nearby housing

- Commercial, for everyday needs at walking distance

- Social infrastructure, as childcare, community centers, co-working

- Green space, to enhance thermal comfort and community well-being

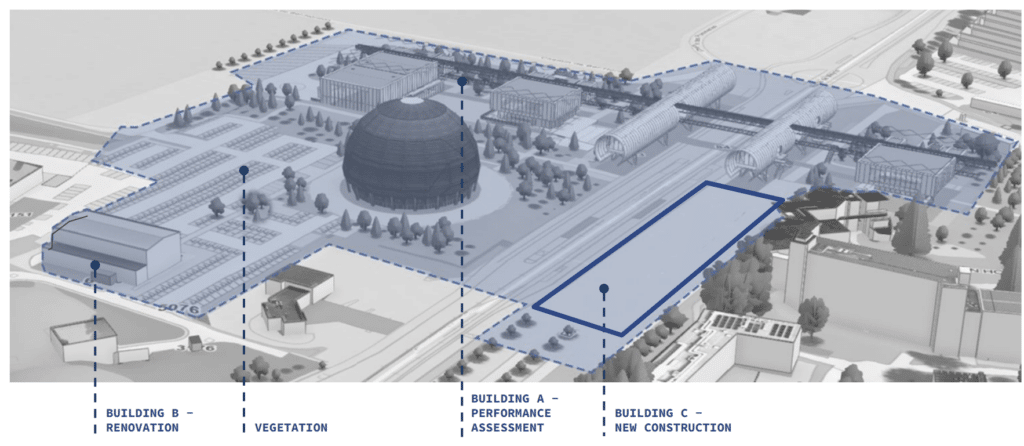

Strategic plan

The project explored multiple strategies to enhance both climate resilience and the hospitality qualities of a scientific–touristic destination. Key approaches included:

- Evaluating energy performance of existing buildings – The Gateway, by Renzo Piano building Workshop – to identify opportunities for efficiency gains.

- Introducing advanced shading systems and renovating a secondary structure to improve comfort and reduce heat loads.

- Designing a new building with sustainability at its core, integrating passive strategies and adaptive forms.

- Incorporating green areas to mitigate heat stress, lower perceived temperatures, and enrich the visitor experience.

Climate Analysis

Climate overview

Geneva has a Temperate oceanic climate – Köppen-Geiger Classification: Cfb.

Key Climate Challenges includes:

- Potential heat waves during summer months with temperatures reaching up to 35°C

- Heavy rainfall events leading to localized flooding risks

- Increased energy demand for cooling in summer and heating in winter

- Urban heat island effect intensifying temperature extremes

- Possible cold snaps in winter with temperatures dropping to -5°C, combined with the Bise -North-East wind- can cause severe icing

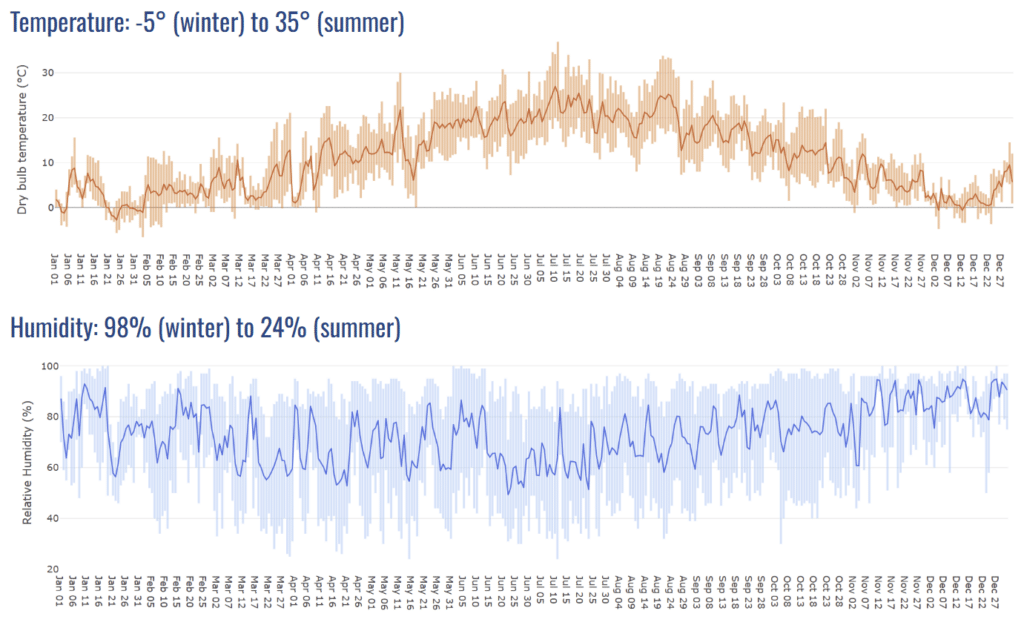

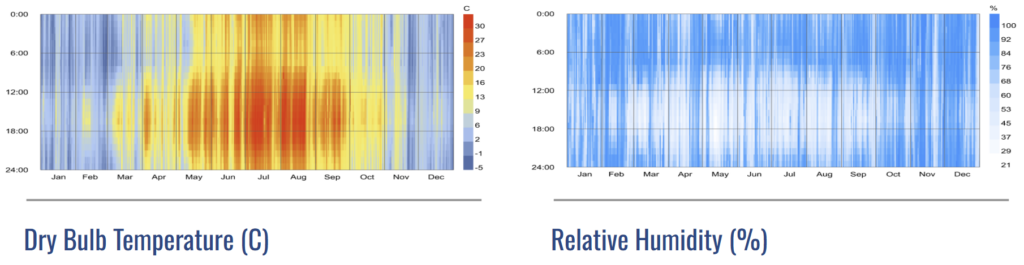

Temperate and Humidity

Overall, Geneva experiences a temperate climate with distinct seasonal contrasts, marked by cool winters and warm summers. The hottest months are July and August, when temperature can reach 35°C, while the coldest is January, when it can drop to -5°C

Relative humidity reflects an inverse correlation with temperature: higher levels in winter (peaking in November) and lower levels in summer (minimum in May).

The interplay of temperature and humidity presents challenges for indoor comfort and moisture control, underscoring the importance of careful consideration in building design and HVAC system selection to achieve both thermal comfort and energy efficiency.

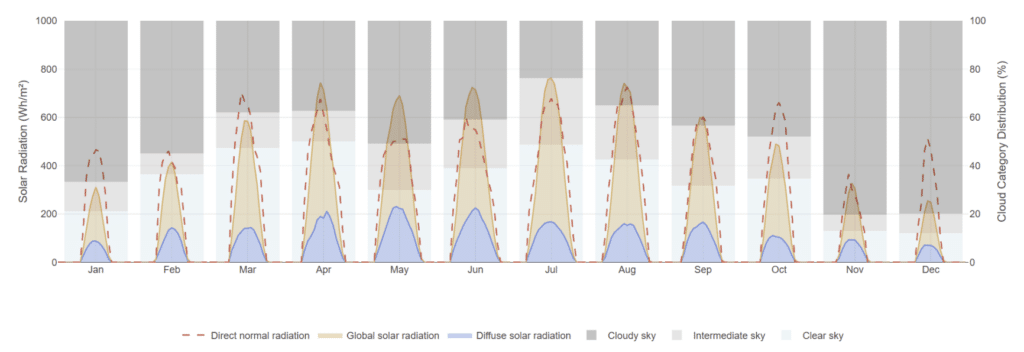

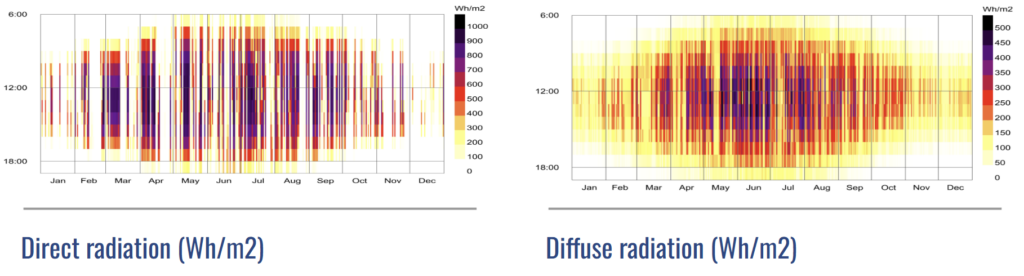

Solar Irradiation & Cloud Coverage

Seasonal patterns emerge also from the solar radiation and sky coverage:

- Summer: Peak radiation and clear skies, requiring robust shading and cooling solutions.

- Winter: Minimal radiation with heavy cloud cover, emphasizing the need to maximize available sunlight for passive heating and daylight.

- Spring/Fall: Moderate radiation with mixed sky conditions, offering balanced opportunities for passive solar design.

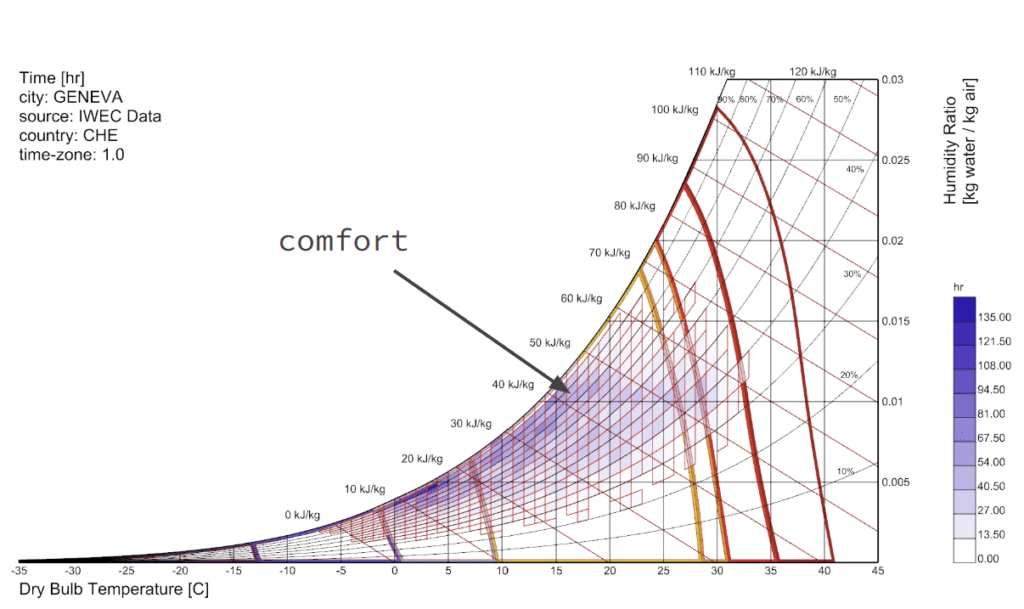

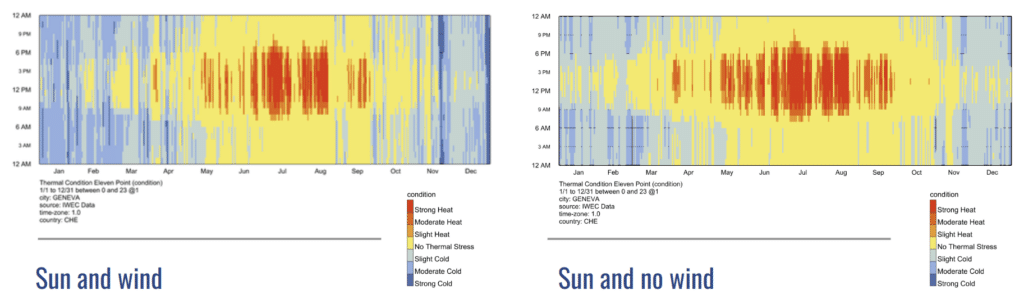

Thermal Comfort

The UTCI on Psychometric Chart highlights both cold and hot stress. The data underscores the importance of robust insulation and efficient heating systems to manage prolonged cold periods. While cooling is secondary, shading and natural ventilation are essential to mitigate summer heat stress. Transitional seasons offer opportunities for passive design strategies, reducing reliance on mechanical systems and enhancing year-round comfort.

Solar exposure emerges as the primary driver of thermal discomfort. Prolonged and direct radiation significantly amplifies hot conditions, raising surface temperatures and intensifying heat accumulation in both indoor and outdoor spaces. As a result, solar control becomes a critical factor in the buildings’ environmental performance, underscoring the importance of façade orientation, shading devices, and vegetation in mitigating excessive heat and improving overall thermal comfort.

Wind plays a significant role as a natural mitigator of heat stress, helping to disperse accumulated hot air and reduce thermal discomfort. This finding reinforces the effectiveness of natural ventilation strategies, confirming that harnessing airflow is essential for improving thermal comfort and ensuring a healthier microclimate within and around the buildings.

Building A – The Gateway

The Gateway

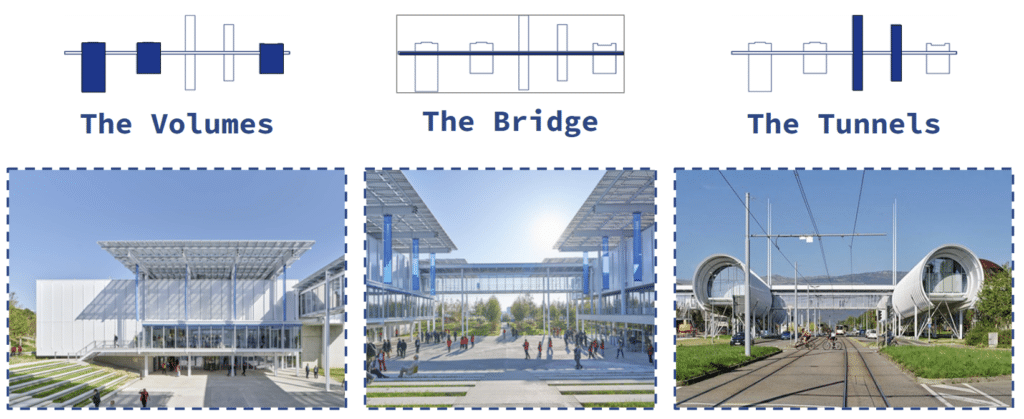

The Gateway is a welcoming building that blends science and culture, offering spaces for visitor exploration, based on three main architectural elements:

The Volumes, The Bridge, and The Tunnels.

Sun Path and Solar Radiation

Using Ladybug and Infrared.city for Sun Path analysis reveals that the solar altitude shifts dramatically throughout the year, ranging from near 0° at the horizon to almost 90° at its peak. This indicates a site with extremely high seasonal variation in solar exposure.

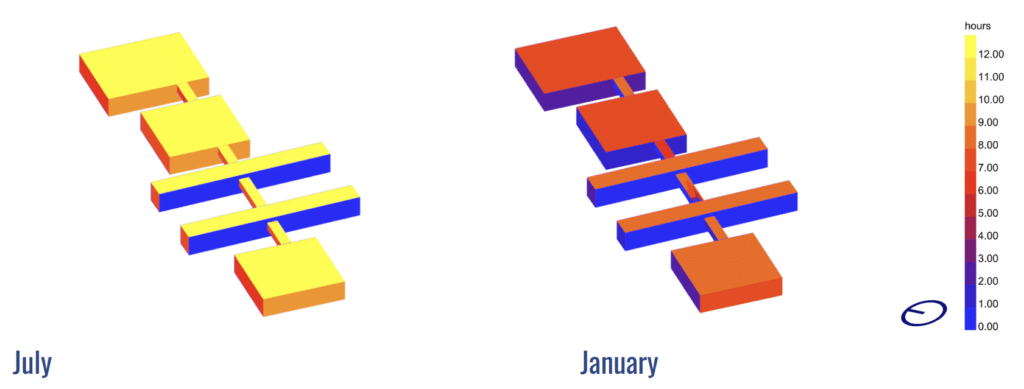

Direct Sun Hours

Direct sunlight patterns change strongly between summer and winter.

In July, long daylight hours allow sunlight to reach deep into the building forms, while tunnel-like sides remain more shaded.

In January, the low-angle sun hits the broad, open faces of the buildings, making them the primary receivers of winter sun and influencing heating performance.

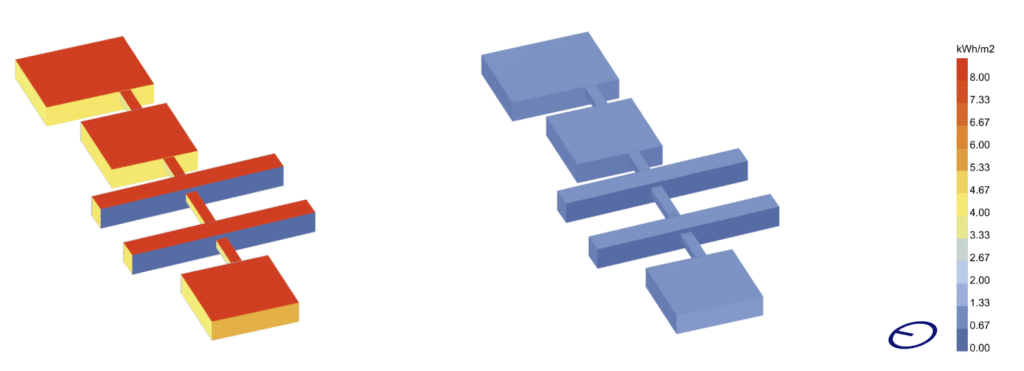

Incident Radiation

Seasonal solar exposure shifts dramatically across the year.

In July, roofs and sun-facing facades receive intense radiation, creating a high risk of overheating and increased cooling demand.

In January, radiation drops considerably, leading to higher heating needs, with only south-facing facades gaining modest passive heat.

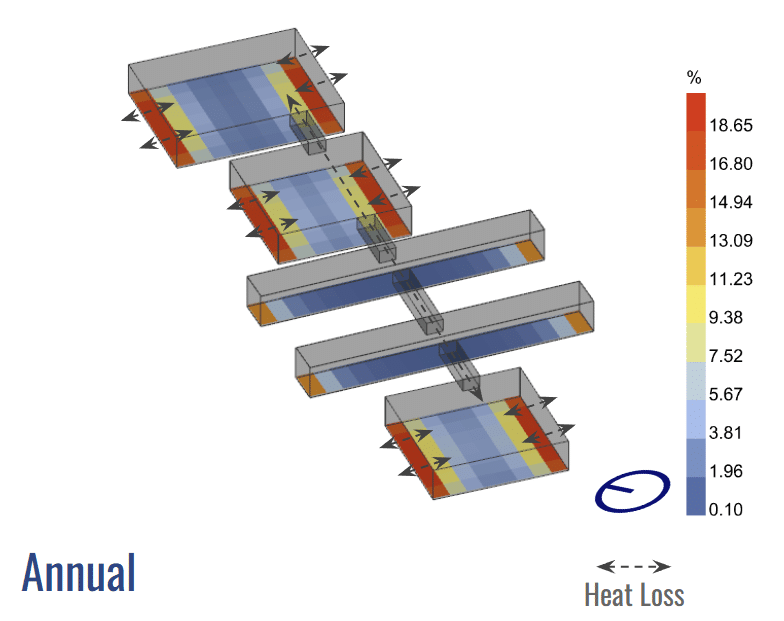

Heat Map

Evaluating the energy efficiency of the building envelope with Honeybee, we found out that: The high values at the edges and connection points indicate areas of significant thermal bridging. The central blue areas show where the system is performing best (lowest heat transfer).

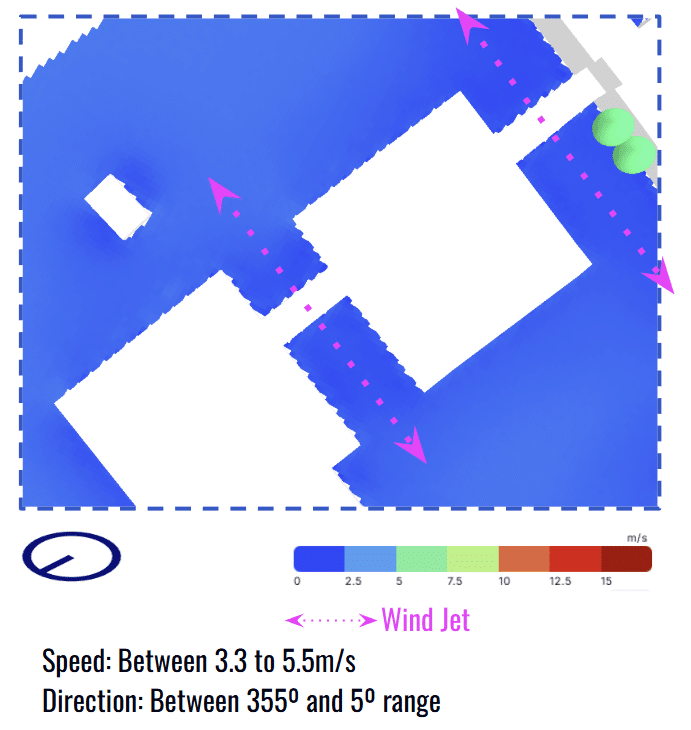

Wind Speed Analysis – Jet Effect

Wind exposure is generally low across the site, except for a mild jet effect between the two building volumes, where channeling slightly increases speeds to 2.5–5.0 m/s and creates a less comfortable micro-climate in that narrow gap.

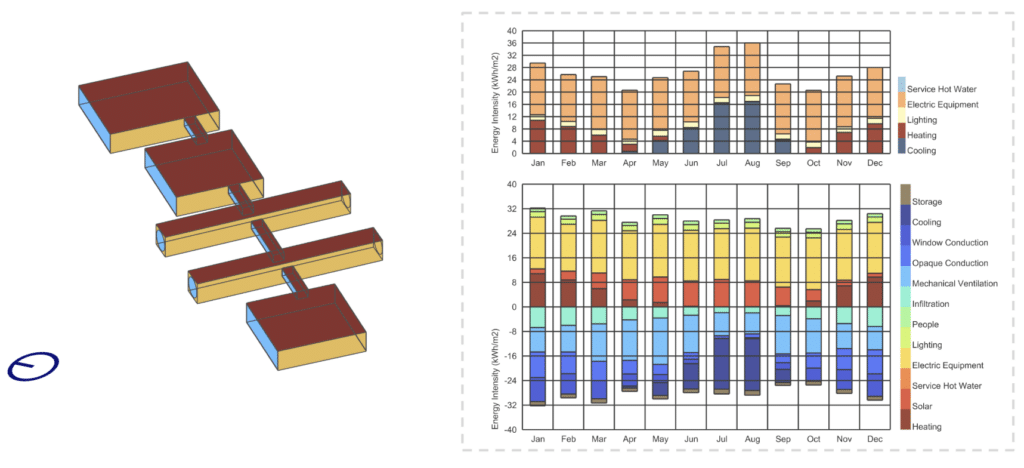

The Energy Profile

The analysis, performed using the Honeybee tool, identified key characteristics and energy loads for the Project.

Key Inputs

- Cool Climate zone

- Steel Structure

- Courthouse typologie

- Simplified geometry

Energy Performance Summary

Total energy use peaks noticeably in July and August, followed closely by December and January. The large thermal envelope losses and unmanaged solar gains are the primary drivers of significant energy waste and high annual energy use. Based on this analysis, the greatest potential for energy savings lies in two critical areas: reducing heat transfer through the building’s envelope and controlling solar exposure. Addressing these factors will lead to the most substantial improvements in efficiency.

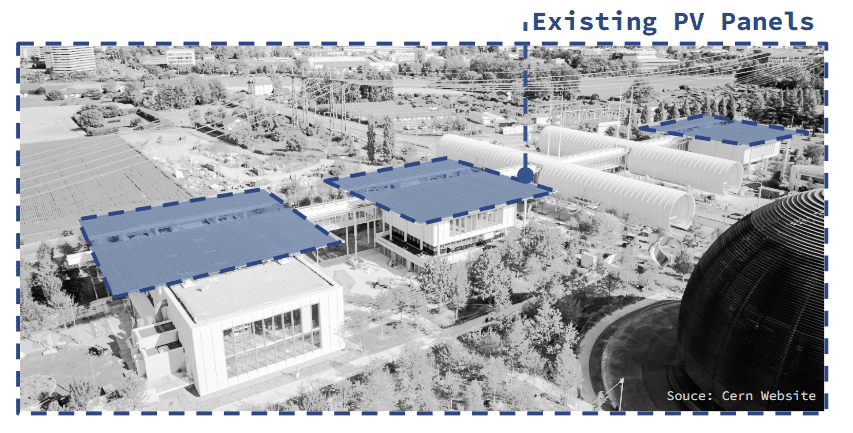

Analyzing PV Panels for Sustainable Energy

To address the high energy load, the project investigated the potential of integrating PV panels.

PV Panel Coverage Analysis

The total energy load for the 7000 m2 CERN Gateway Area is 2,238,240 kWh/year. The analysis shows that PV panels currently installed can achieve an annual AC production of 828,464 kWh. This results in a coverage of 37.01% of the total annual energy load.

Remaining Load and Improvements

While the coverage is good, the remaining energy load of 1,409,775 $\text{kWh/year}$ is still considered high for a building of this size.

Possible improvements include:

- Adding more PV panels if roof or façade space is available.

- Cutting the building’s energy use to lower the current load intensity by implementing architectural mitigations.

Further analysis is recommended.

Building B – New Facade System

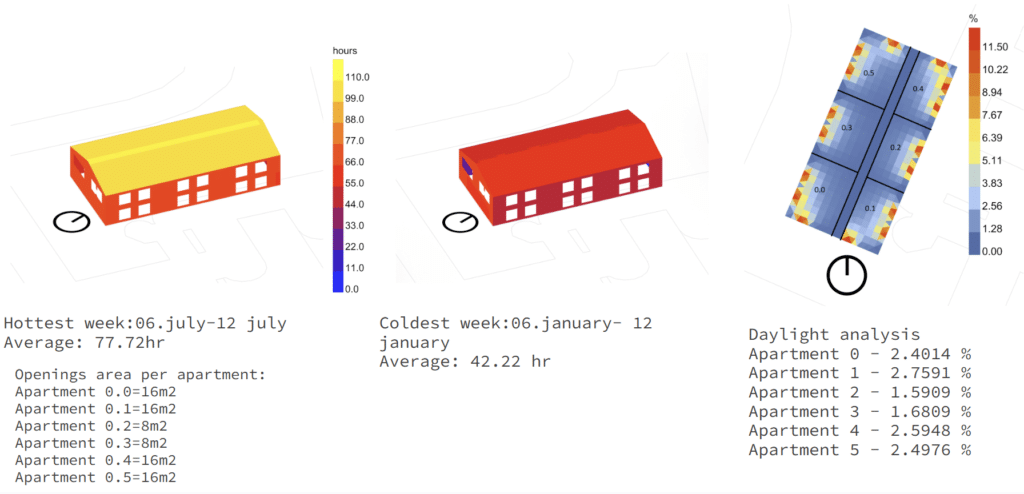

Building B is existing building with no current use. As part of the study is proposed to host residential units for use of the CERN campus users. The building was separated in two floors with 6 apartments each. The apartments are small, 60m2 apartments meant for few days stay.

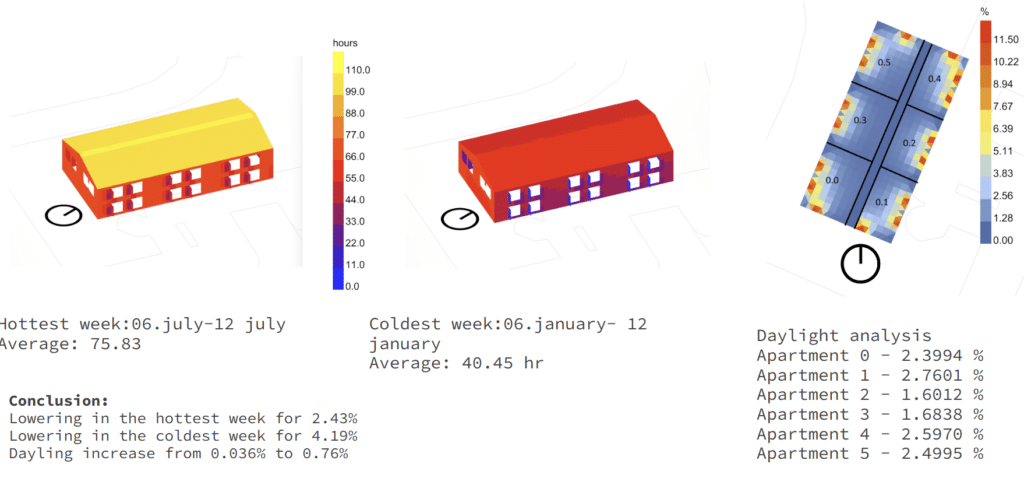

Base scenario

A base scenario was tested in order to obtain reference values. The facade was tested for direct sun hours in both, the hottest and the coldest week, while the interior layout was tested for daylight. Two of the apartments received below 2% daylight.

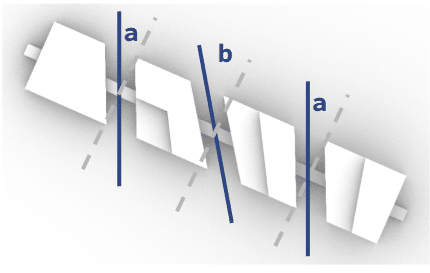

Vertical Shading

Second scenario was tested in which vertical shading was introduced along each of the apartment’s windows. Improvement was noticed in the lowering of the direct sun hours on the facade which ranged from 2.43% during the hottest week and 4.19% for the coldest week in the year. Although small the daylight analysis showed increase in the daylight the apartments were getting ranging from 0.036% up to 0.76%.

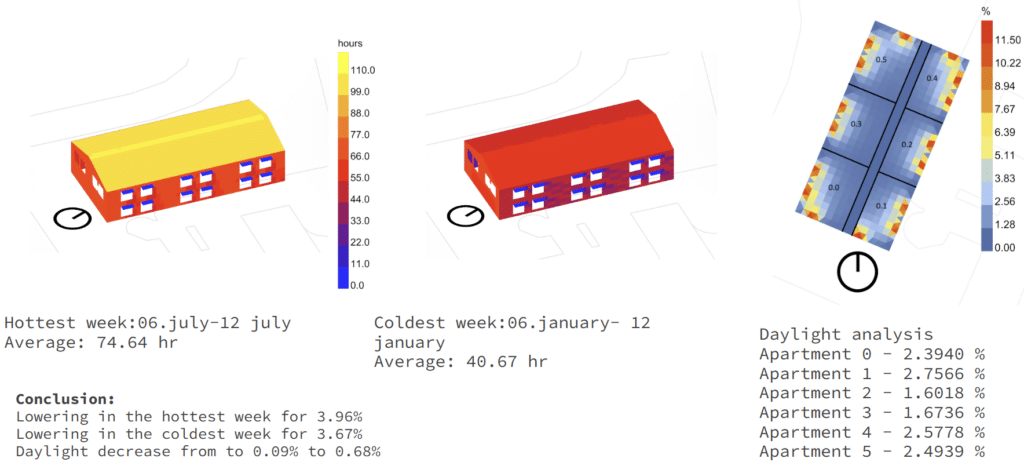

Horizontal Shading

In the third scenario horizontal shading were placed above each of the windows. The values obtained for the direct sun analysis showed lowering for 3.96% during the hottest week and 3.67% during the coldest week of the year. The daylight in the apartments decreased from 0.09% to 0.68%

Building C – New climate-adaptive building

Workflow

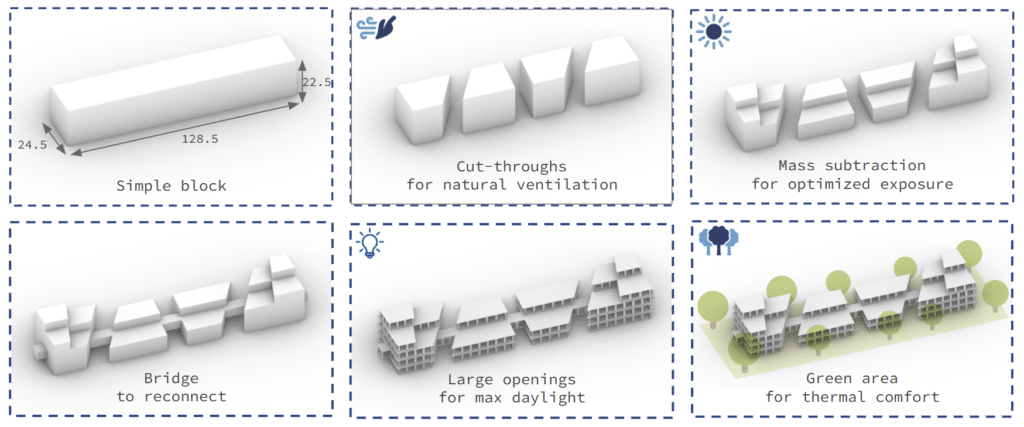

The new building’s design process is structured in multiple phases, each targeting the optimization of a distinct climate aspect.

- The concept begins with a simple block.

- Strategic cut-throughs enhance permeability and promote natural ventilation, creating a more open and breathable structure.

- Mass is then subtracted to optimize solar exposure, ensuring that the building benefits from maximum daylight throughout the year.

- The façade incorporates large openings to amplify daylight penetration, while integrated greenery contributes to thermal comfort, shading, and a more resilient microclimate.

Together, these strategies establish a climate-responsive architecture that balances simplicity of form with environmental performance.

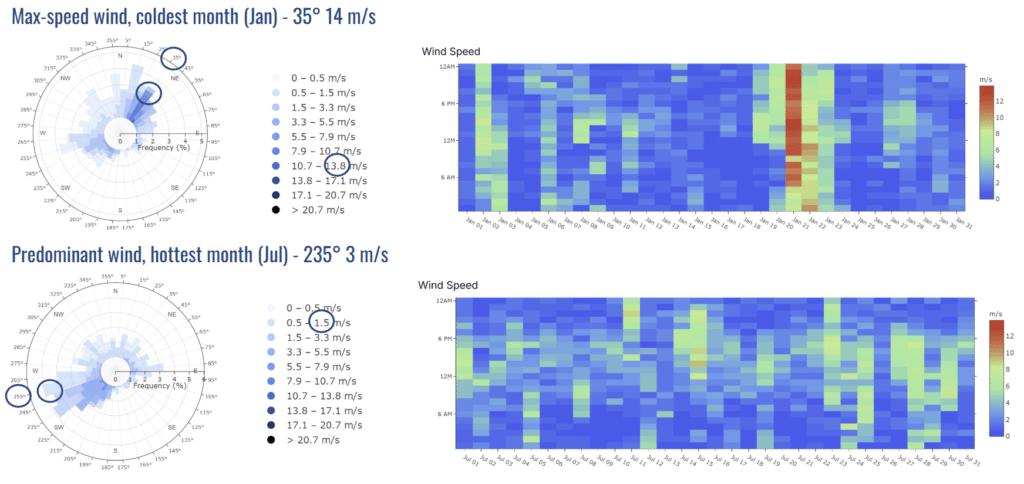

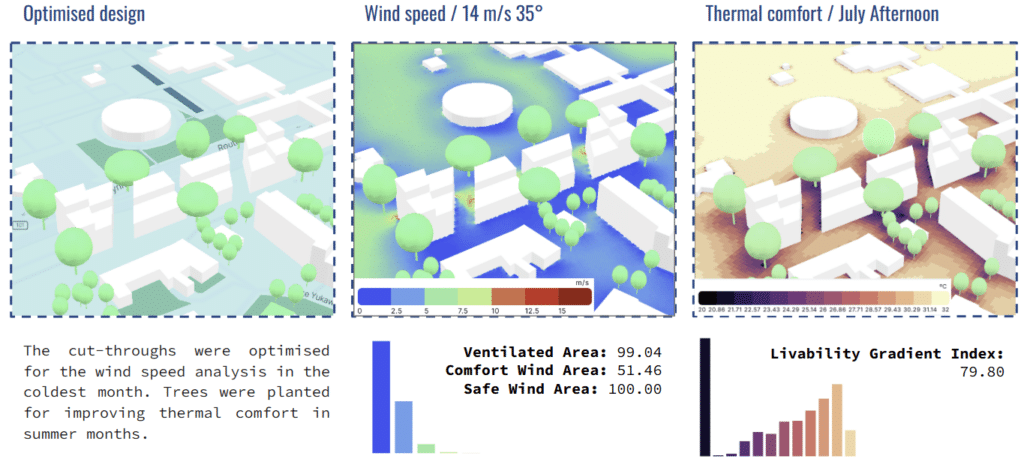

Wind speed

The initial aim was to optimize natural ventilation during the summer months. However, the analysis revealed that wind speeds in Geneva are too low in the hottest periods, and in some cases even counterproductive, as hot air movement can reduce comfort rather than improve it.

As a result, the study concentrated on winter conditions, where evolutionary optimization was used to balance areas with excessively slow or fast winds. In this season, higher wind velocities were penalized three times more, leading to a building form specifically adapted to enhance thermal comfort during cold periods.

Optimization goal: Minimize %_slow and %_fast

%_slow: area with wind speed < 2 m/s

%_fast: area with wind speed > 6 m/s

Fitness: Weighted average (w1: 1, w2: 3)

Genome: alpha, beta (domain: -35,35)

To achieve finer resolution, the fitness function was restricted to the results within the building’s immediate context.

The optimization process identified an optimal solution in which the building incorporates cut‑throughs oriented at –30° and –5°. As a result, the proportion of uncomfortable zones decreased to 19.12%, demonstrating how targeted geometric adjustments can significantly enhance micro-climatic performance.

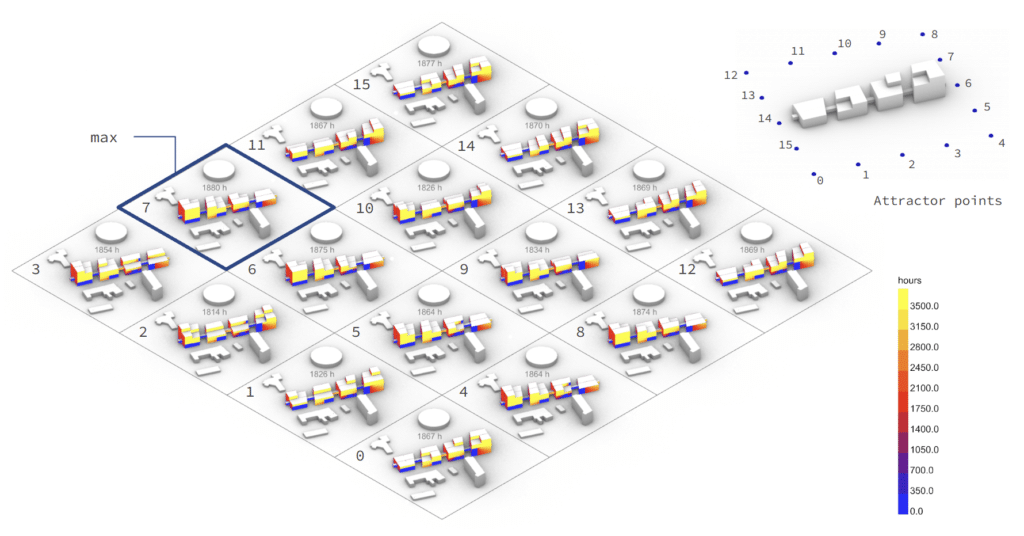

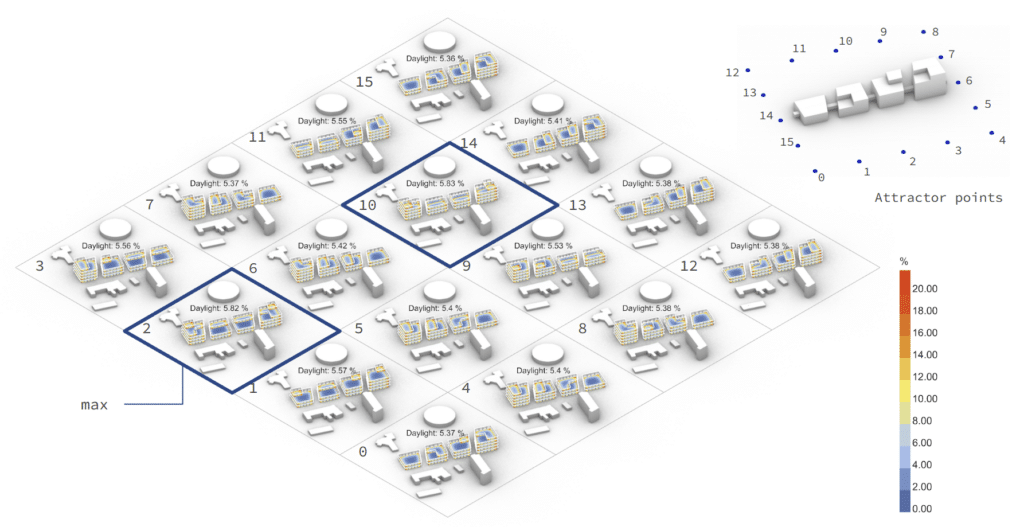

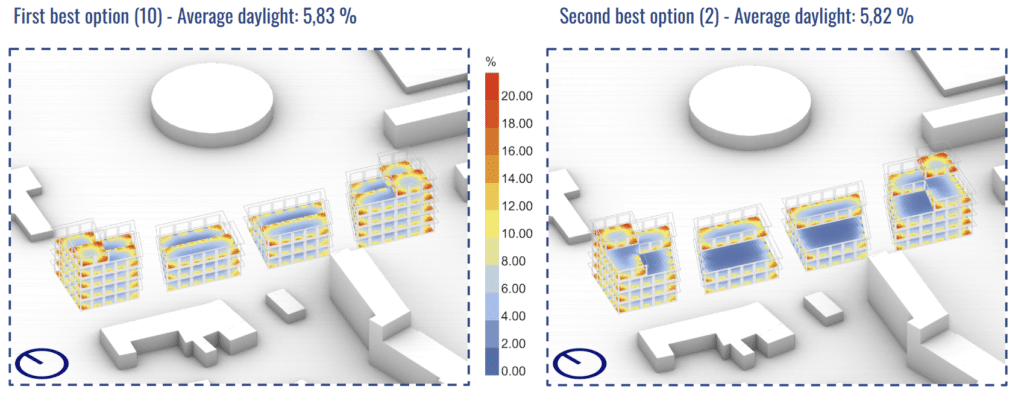

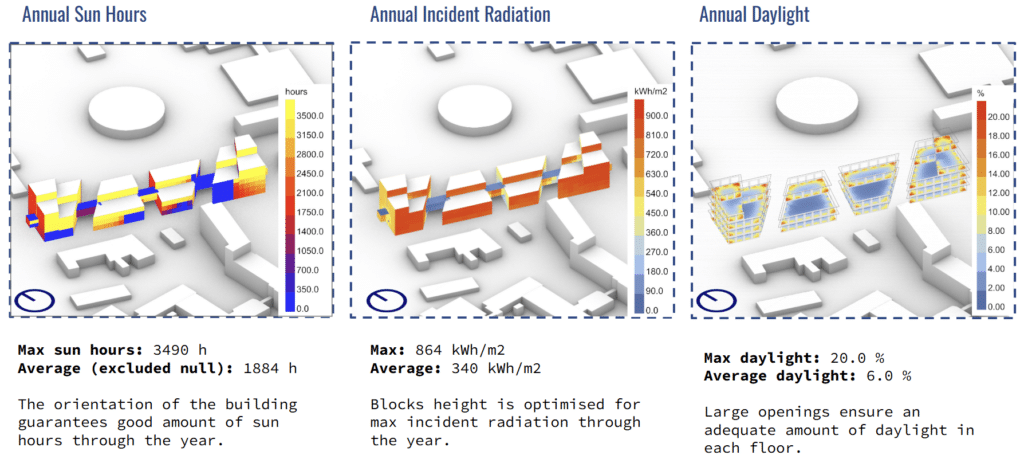

Direct Sun Hours

To maximize annual sun hours across the site, we conducted a systematic exploration of 16 design options, each derived from a parametric process using 16 attractor points to drive mass subtraction. This iterative method allowed us to test a wide spectrum of volumetric configurations, evaluating how subtle shifts in geometry and orientation influenced solar access throughout the year. The most effective solution featured a higher south-facing façade, achieving an average of 1,880 direct sun hours annually.

Solar Irradiation

When we repeated the study using incident radiation as the primary metric, the optimal configuration shifted toward a more balanced, symmetric distribution of building height. This form achieved an average of 343 kWh/m², reflecting improved overall solar performance. The result highlights how different evaluation criteria can lead to distinct design outcomes, underscoring the importance of aligning form-finding strategies with specific environmental goals.

Daylight

For daylight, the performance across all 16 design options proved nearly identical, with values averaging around 5.5%. This consistency is largely attributed to the surrounding urban context: nearby buildings are predominantly low-rise, and the area benefits from generous open spaces and wide streets. As a result, daylight access remains relatively unobstructed regardless of the tested massing variations.

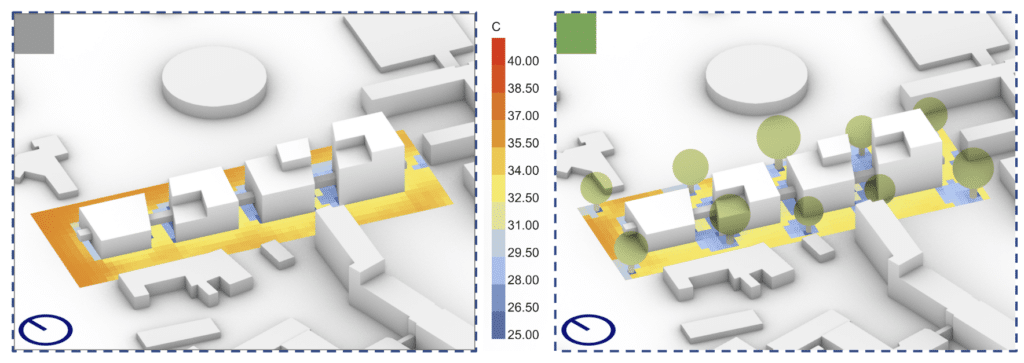

Thermal Comfort

A UTCI analysis was conducted with Honeybee tool on the hottest day, 10th of July, 12:00-13:00. The result was that changing the ground material from concrete pavement to grassy lawn reduces perceived temperature of about 1°C.

The same analysis was run in Ladybug, which resulted in a lower thermal stress, due to the fact that the tool does not allow to input ground material. The focus this time was on vegetation: planting 10 trees (English oaks) around the building would again decrease the perceived temperature of 1°C, further improving thermal comfort.

Summary

The final building form incorporates cut-throughs inclined at -35° and -5°, strategically introduced to improve the aerodynamic performance of the overall massing. These interventions allowed for a measurable increase in the comfort wind area by approximately 10%, ensuring that pedestrian zones around the building benefit from reduced turbulence and more favorable micro-climatic conditions in winter. Furthermore, the integration of greenery around the building significantly improved outdoor comfort by lowering the perceived temperature by approximately 2 °C in the hottest month.

In addition to the wind-related improvements, the volumetric modulation of the building—specifically the gradual decrease in height from the outer edges toward the central core—proved highly effective in optimizing solar exposure. This design move enhanced the average solar irradiation received on the façades by nearly 50 kWh/m² per year, contributing to better daylight penetration, improved energy efficiency, and greater potential for passive heating strategies.

Together, these adjustments demonstrate how subtle geometric manipulations of the building envelope can simultaneously elevate environmental performance and occupant comfort, while reinforcing the architectural identity of the project.

Further analysis may include:

- Distribution of activities within each building block, based on daylight availability and indoor thermal comfort.

- Detailed facade design and a comparative analysis of diverse shading systems, similar to the study conducted for Building B.

- Evaluation of the effect of trees on pedestrian wind comfort.

Conclusions

The analysis highlights key opportunities to strengthen the architectural and environmental performance of the CERN gateway area. The aim is to transform this area into a more climate-resilient and inviting urban core while respecting existing structures.

Key observation

- Climate adaptation: Geneva’s climate brings strong summer solar exposure and noticeable thermal discomfort from late May to September. The design must balance winter solar gains with reliable summer shading.

- Existing buildings: Improving the façade and overall envelope of existing buildings offers the greatest potential for reducing heating and cooling loads.

- Extended program: The proposal introduces new buildings and green spaces to create a cohesive environment that supports hospitality, residential, social, and commercial uses for visitors and scientists.

This strategy integrates essential mixed-use functions while boosting environmental performance and user comfort across the CERN gateway environment, preparing the site to welcome a growing number of visitors. Together, the proposed interventions demonstrate how architectural design, environmental analysis, and landscape integration can converge to create spaces that are not only technically efficient but also welcoming, resilient, and aligned with the needs of both science and tourism.