Abstract : In recent years, urban cores across the world have entered a period of uncertainty. Accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the widespread adoption of hybrid work, many central business districts (CBDs) have experienced declining footfall, rising commercial vacancy, and shifts in social life—while others have demonstrated surprising resilience. This project investigates how foundational urban theories can help interpret these uneven transformations. Using a mixed-method approach that combines quantitative spatial analysis with qualitative theoretical inquiry, we revisit early twentieth-century models of the city alongside contemporary urban thought. By extracting measurable parameters from classical theories and mapping them across U.S. cities using open-source geospatial data, this research explores whether historical frameworks still resonate within today’s urban conditions. Rather than seeking a single definition or future for the urban core, the project positions theory as an interpretive lens through which the evolving complexity of contemporary cities can be read.

Why Study Urban Cores Today?

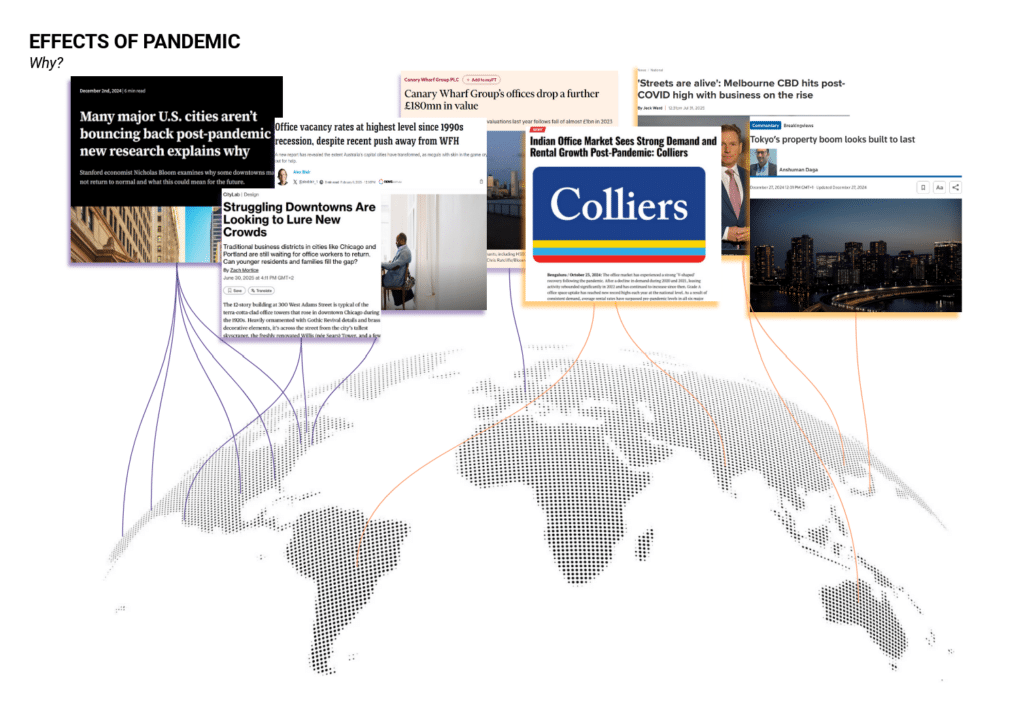

Conversations within our studio—and casual observations of our own cities—revealed a shared experience: downtowns that once felt vibrant now appeared quieter, fragmented, or active only on select days of the week. The pandemic did not create these shifts, but it accelerated processes already underway—digitization, flexible work patterns, and changing expectations of urban life.

Urban cores remain critical sites of economic concentration, infrastructure investment, and symbolic identity. Yet these same characteristics make them especially vulnerable to changes in how and where people work. Rising vacancy rates introduce the risk of what urban economists describe as an urban doom loop, where declining activity leads to reduced services, shrinking tax bases, and further disinvestment. Understanding the spatial structure of urban cores has therefore become both an analytical and a civic concern.

Revisiting Foundational Urban Theories

To frame our investigation, we returned to the origins of CBD theory. Early urban models—developed primarily in the early twentieth century—offered simplified but powerful explanations of how cities organize themselves.

- The Concentric Zone Model conceptualized the city as a series of rings radiating outward from a commercial core.

- The Sector Model emphasized growth along transportation corridors, producing wedge-shaped land-use patterns.

- The Multiple-Nuclei Model challenged the idea of a single center, proposing instead that cities develop around multiple specialized nodes.

Although these models were developed with limited empirical tools, they continue to influence how cities are planned, zoned, and imagined. Our research asks not whether these diagrams are correct, but whether their underlying logic can still be observed in contemporary urban form.

Methodology : A mixed – methods approach

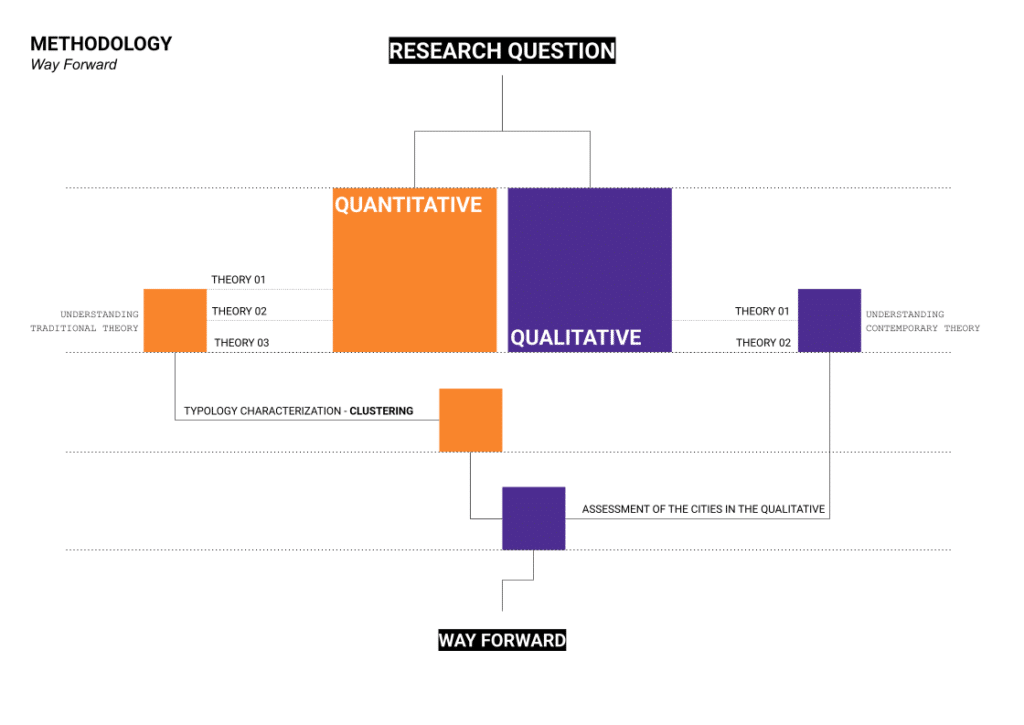

Our methodology combines quantitative spatial analysis with qualitative interpretation.

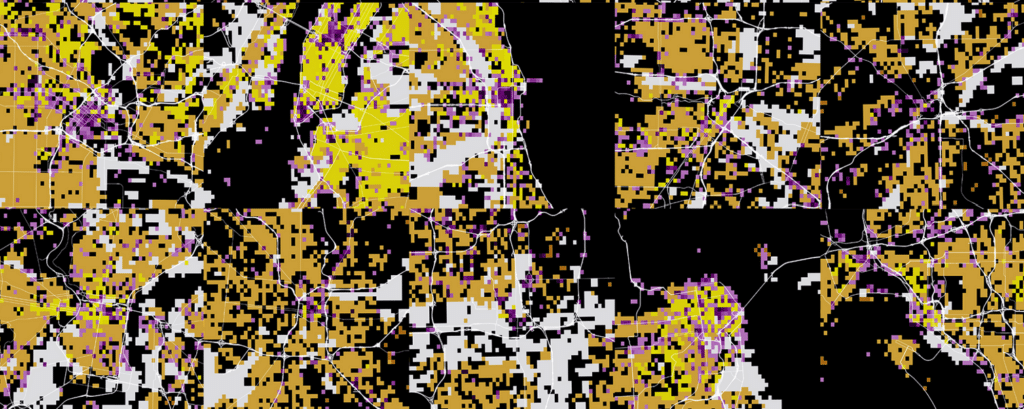

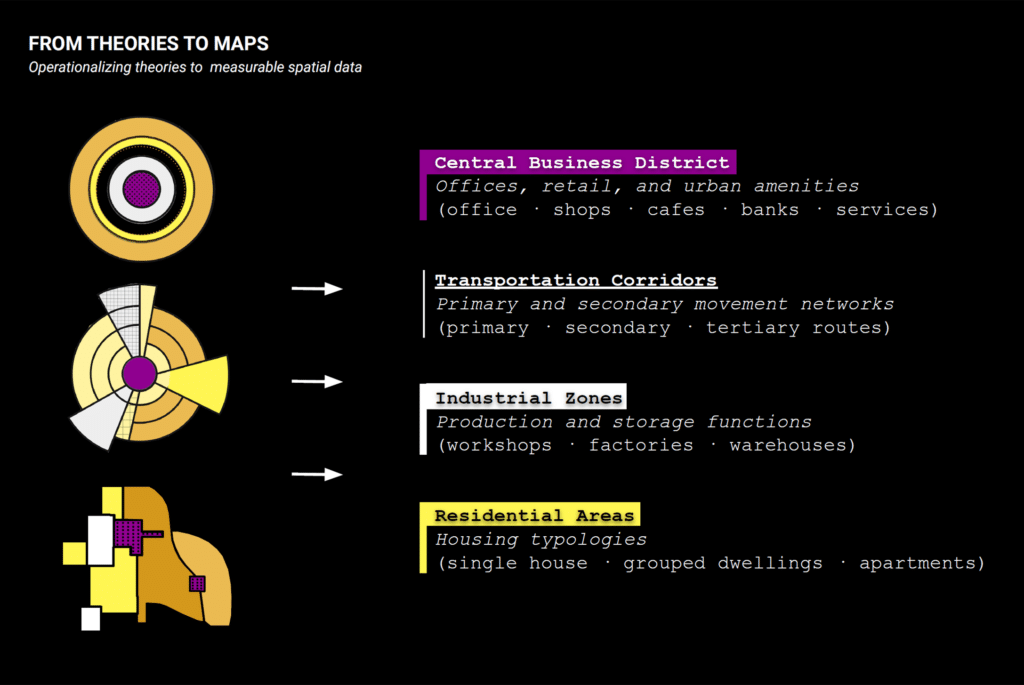

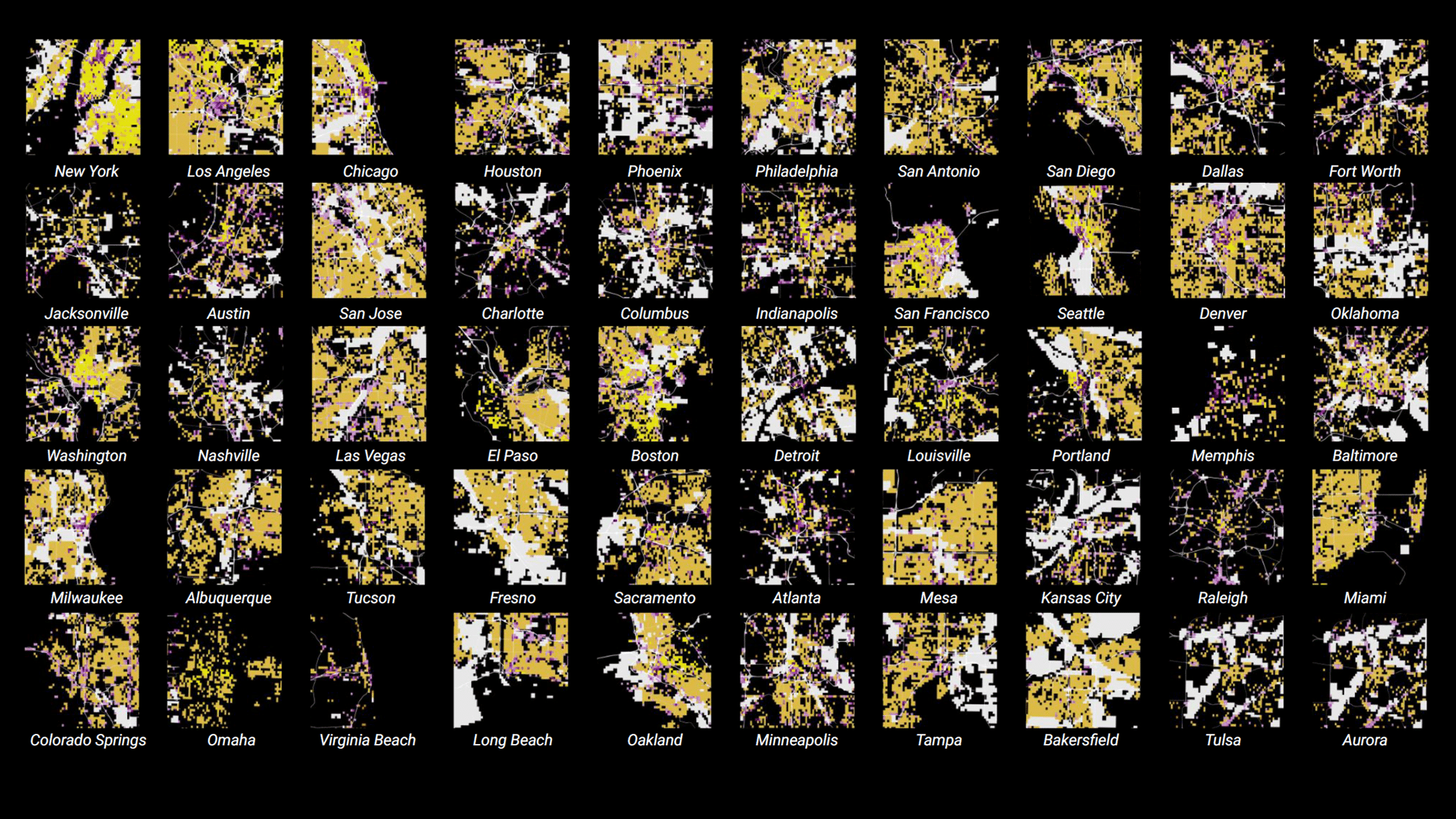

On the quantitative side, we extracted core parameters embedded within foundational theories—commercial activity, industrial land use, transportation infrastructure, and residential density. Using open-source datasets, we mapped these layers across major U.S. cities. Each city was analyzed within a 10-kilometer radius from its central point, using a 300 x 300 meter grid to allow for comparative reading. Rasterization and clustering techniques were then applied across fifty of the most populous U.S. cities to identify recurring spatial typologies.

In parallel, our qualitative approach draws from contemporary urban thinkers who challenge purely economic definitions of the urban core. Rather than focusing on singular centers, these perspectives emphasize mixed use, public life, accessibility, and lived experience. These ideas informed additional mappings of density, mixed-use areas, open spaces, and pedestrian infrastructure—acknowledging both the value and limitations of measurable proxies.

Reading the Contemporary Urban Core

For each of the land-use categories outlined in the foundational theories, we used vector point data from Open Street Map to locate commercial activities along land-use data from Google Earth Engine. This was done in lieu of municipal zoning data as it could be replicated to map cities across the entire United States. We started by mapping each of the land-uses individually to see distribution patterns, and then merged them together to create one final diagrammatic land-use map.

Our results reveal that no city conforms neatly to a single historical model. Some cities still exhibit sectoral or concentric tendencies, particularly where industrial and residential patterns follow major transit corridors. Others display clear multi-nodal structures, with dispersed centers of activity rather than a dominant CBD.

More importantly, many cities reflect hybrid conditions, where multiple theoretical models coexist. These findings suggest that foundational theories remain relevant—but not as prescriptive diagrams. Instead, they function as analytical tools that help reveal how different spatial logics overlap and interact in real time.

Experimenting in Mapping the Nuance of Cities

Following our methodology, we turned to mapping the qualitative aspects of cities. Contemporary urban theory understands the urban core as increasingly diffuse: the CBD is no longer a singular location, but a complex environment composed of overlapping tangible and intangible layers.

To explore the qualitative nature of downtown, we focused on Jane Jacobs and Jan Gehl. Both challenge the idea that cities can be understood solely through land use or economic activity, instead emphasizing human experience, social interaction, and everyday life. Though largely observational rather than diagrammatic, their work is critical for understanding how contemporary urban cores function beyond abstract planning models.

We then translated selected ideas from Jacobs and Gehl into measurable mapping parameters. Inspired by Jacobs, we mapped building and population density alongside mixed-use areas to identify potential overlaps with the urban core. Gehl’s ideas were explored through mappings of open spaces, in-between spaces, sidewalks, and pedestrian crossings, aiming to visualize accessibility and movement at the human scale. However, the limited availability of qualitative data highlights the need for long-term comparisons to better understand how these layers evolve over time.

Attempts to merge quantitative and qualitative readings into a single composite image proved counterproductive. Flattening multiple dimensions of urban life into one representation often obscured more than it clarified. Urban complexity, we found, is better understood through layered interpretations, allowing each framework to speak independently.

Conclusion: Theory as a Tool, Not a Template

This project does not aim to predict the future of downtowns, nor to define a universal model for the urban core. Instead, it demonstrates that cities resist singular explanations. Foundational urban theories continue to offer value—not because they describe cities perfectly, but because they provide structured ways to interpret change.

In a moment when hybrid work, digital infrastructure, and shifting social practices are reshaping urban life, the urban core emerges not as a fixed spatial entity, but as a dynamic, layered system. By revisiting historical models through contemporary data and theory, this research re-frames the CBD as an evolving condition—one that adapts, fragments, and reorganizes in response to broader socioeconomic transformations.

Ultimately, understanding urban cores today requires moving beyond definitive diagrams toward plural readings—where theory becomes a lens for interpretation rather than a blueprint for the future.