Our project embarked on a mission to tackle global shipping piracy without resorting to military action. We faced a major challenge: finding and using publicly available information to craft a proposal that countries and international organizations would support.

1. WHY SHIPPING PIRACY?

Within the context of Networked Flows, our directive was to pinpoint potential disruptions within network dynamics. Guided by this objective, we explored the global shipping network, seeking out conceivable conflicts that could impede its smooth operation. Among the array of potential challenges, maritime piracy emerged as a particularly intricate yet captivating choice. Central to our thesis was the recognition of piracy as a tangible manifestation of localized conflict, capable of severely hampering global trade flows and jeopardizing human lives. Organizations like NATO estimate that “piracy costs Global shipping $7 to $12 billion per year (Excluding ransomware)” and The Maritime Executive writes that “hostage experiences are related to a significantly increased risk of PTSD”. Keeping to our narrative, we chose to focus on combating shipping piracy because it threatens people’s wellbeing and negatively impacts the global economy.

2. PIRACY BACKGROUND AND ANALYSIS LOGIC

Looking at online reports it was immediately obvious that piracy cases have different roots, depending on their location. While in the Gulf of Aden the main cause why piracy started to take was illegal fishing which was further fueled by corruption and civil war, in the Malacca Straits, heavy maritime traffic, poor law enforcement and a poor socio-economic context were fundamental to fueling piracy activities. At a first glance it was clear that pirates follow quick monetary gains, but we wanted to look at a larger scale and understand if there are other reasons why piracy could appear in some countries? Besides proximity to global shipping routes, are there other reasons and why?

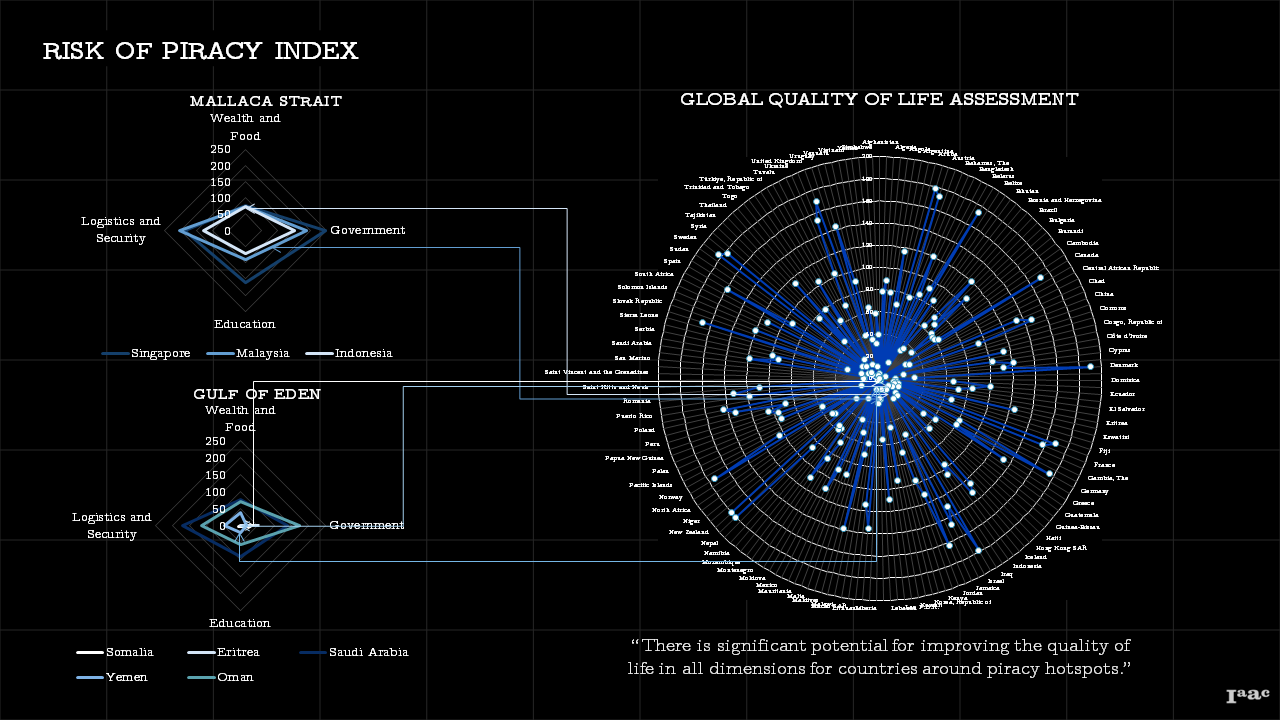

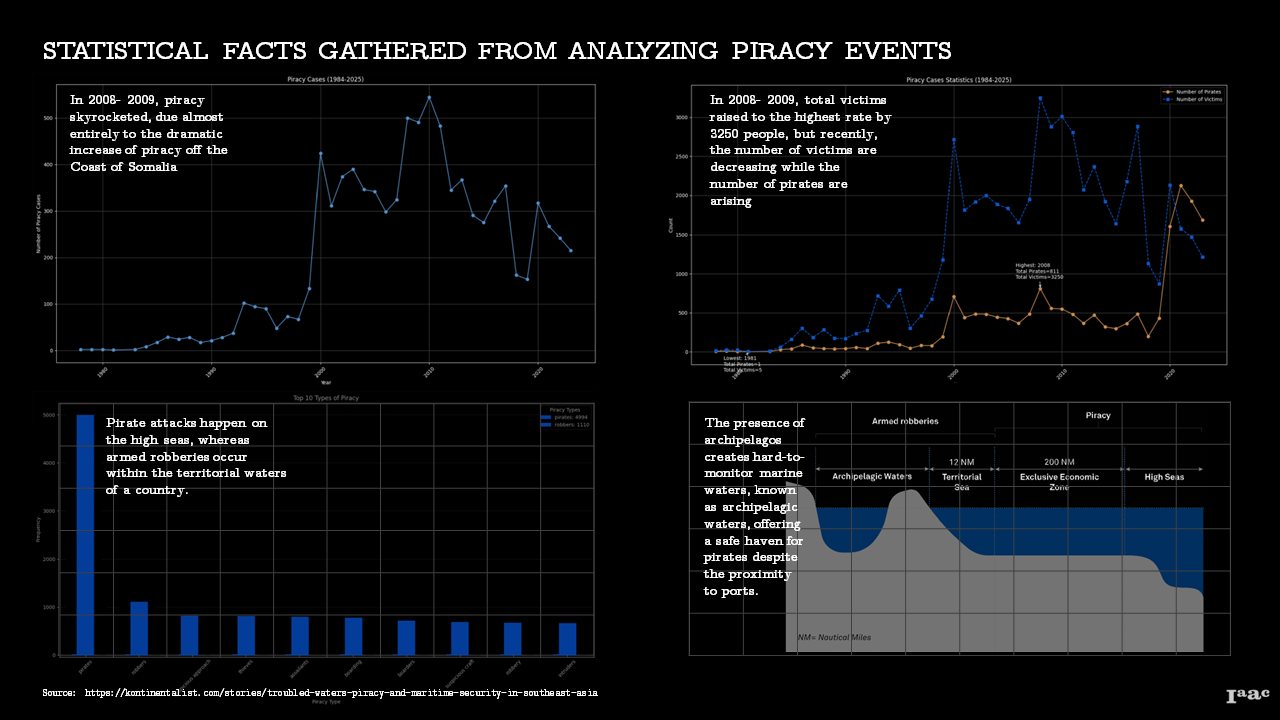

To create a possible data backed framework, we decided to do two sets of analysis: a statistical analysis and a geographical spatial analysis. The statistical macroscale analysis would allow us to classify all countries after a Piracy Risk Index, and thus establish where policies are needed. The geographical analysis would allow us to better understand the specifics of the areas so that the policies that are proposed are targeted to the specificity of those areas.

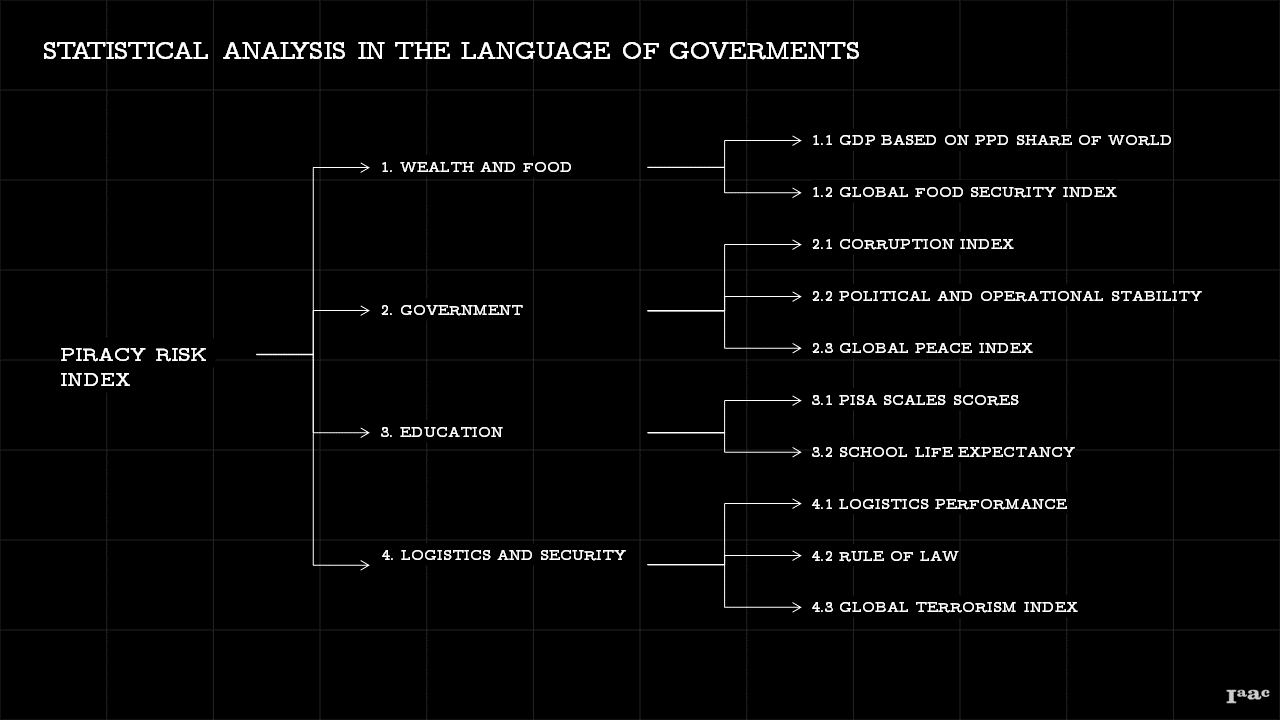

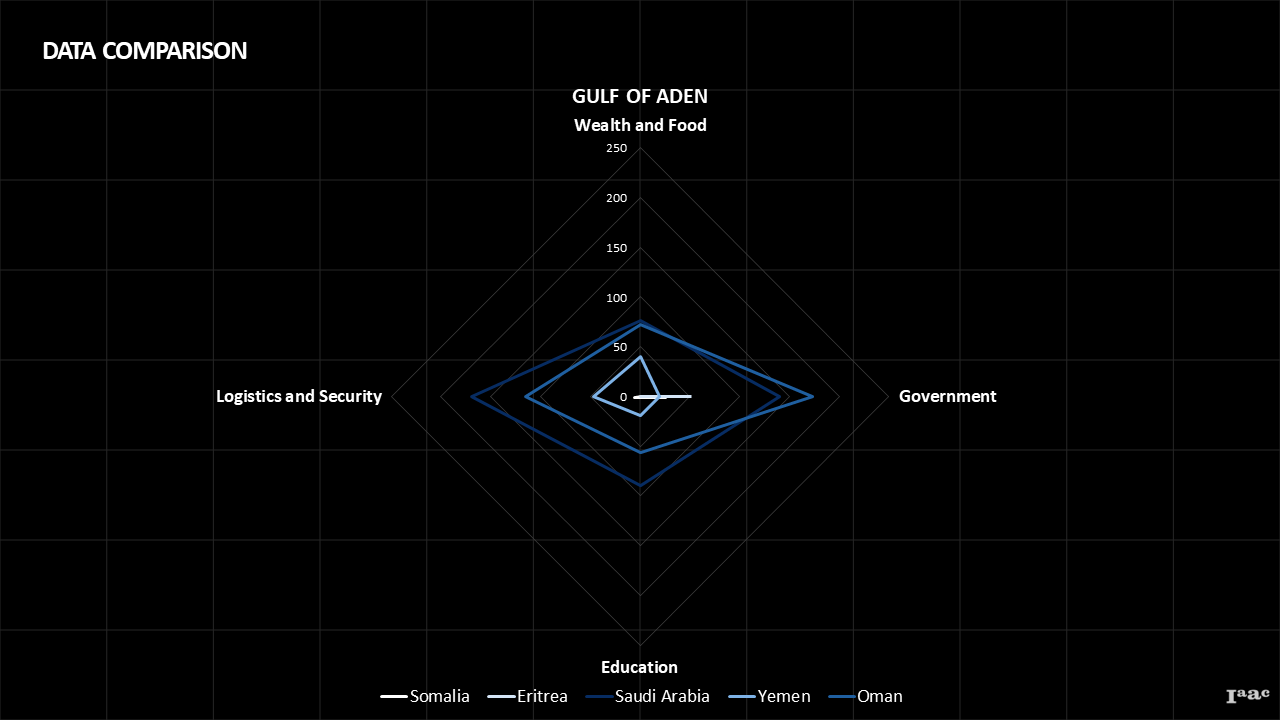

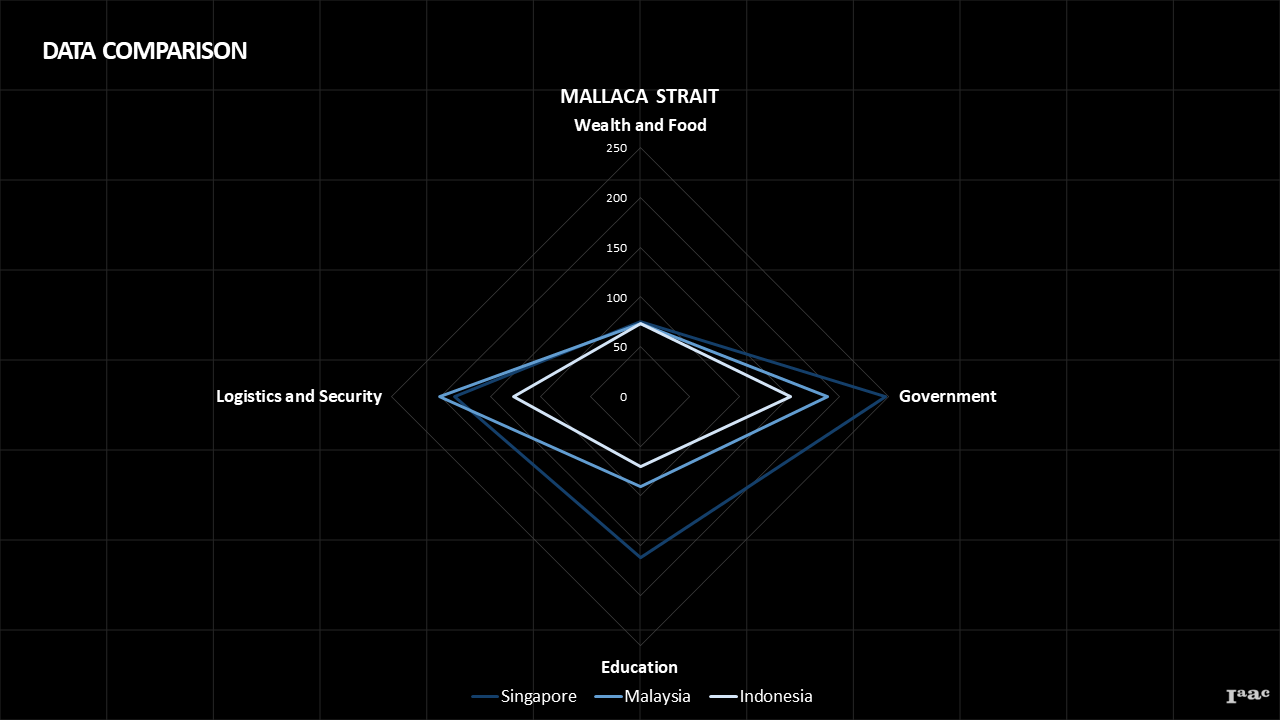

The framework that we propose was to score, classify and analyze every country in the world on 4 main pillars: Wealth and Food, Government, Education, Logistics and Security. Each pillar is composed of an average of 2 or more indicators taken from renowned international organizations. For each indicator, the data is normalized by attributing the best country in the world a score of 100 while the worst gets a score of 1. We thus obtained a master database that we could use to analyze and compare countries from different regions in the World.

- Wealth and Food – this pillar sets out to measures whether the population has accesses to food resources and can afford to buy food. The logic behind this is that if people are not starving they are less likely to engage in piracy activities.

1.1. GDP based on PPP (Purchasing Power Parity) share of the world – refers to the percentage of the global economy that a country represents when adjusting for differences in price levels across countries. (public data from IMF)

1.2 Global food security index – The index ranks each countries food security based on 5 indicators: affordability, availability, quality and safety and sustainability and adaptation. (public data from The Economist) - Government – this pillar sets out to measure how stable a country is. Historical analysis showed that piracy is more likely to occur in countries that are on the verge of civil war or that have corrupt governments and political instability.

2.1 Corruption index – This indicator measures the perceived levels of public sector corruption. (public data from Transparency International)

2.2 Political and operational stability – This indicator is an index that measures the likelihood and severity of political, legal, operational or security risks affecting business operations. (public data from S&P Global)

2.3 – Global peace index – The Global Peace Index (GPI) ranks the peacefulness of countries and regions worldwide based on safety and security, conflict levels, and militarization. (public data from the Institute for Economics and Peace) - Education – this pillar sets out to measure the perceived levels of education in a country. The logic behind is that low levels of education will contribute to a higher probability of piracy to occur.

3.1 PISA scales scores – PISA is the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment. PISA measures 15-year-olds’ ability to use their reading, mathematics and science knowledge skills. (public data from OECD)

3.2 School life expectancy – Total number of years that a person of school entrance age can expect to spend within the primary to tertiary levels of education. (public data from UNESCO) - Logistics and Security – this pillar sets out to measure if a country possesses the capabilities and intention to combat piracy or it can be a sprawling place for potential pirates.

4.1 Logistics performance – A multidimensional assessment of logistics performance, the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) ranks countries combining data on six core performance components—including customs performance, infrastructure quality, and timeliness of shipments. (public data from the World Bank)

4.2 Rule of law – This indicator is an index that reflects the perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence. (public data from the World Bank)

4.3 Global terrorism index – The GTI reveals the severity and distribution of terrorism’s impact across countries by ranking them based on terror-related activities and their consequences. (public data from the Institute for Economics and Peace)

3. MACRO SCALE STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

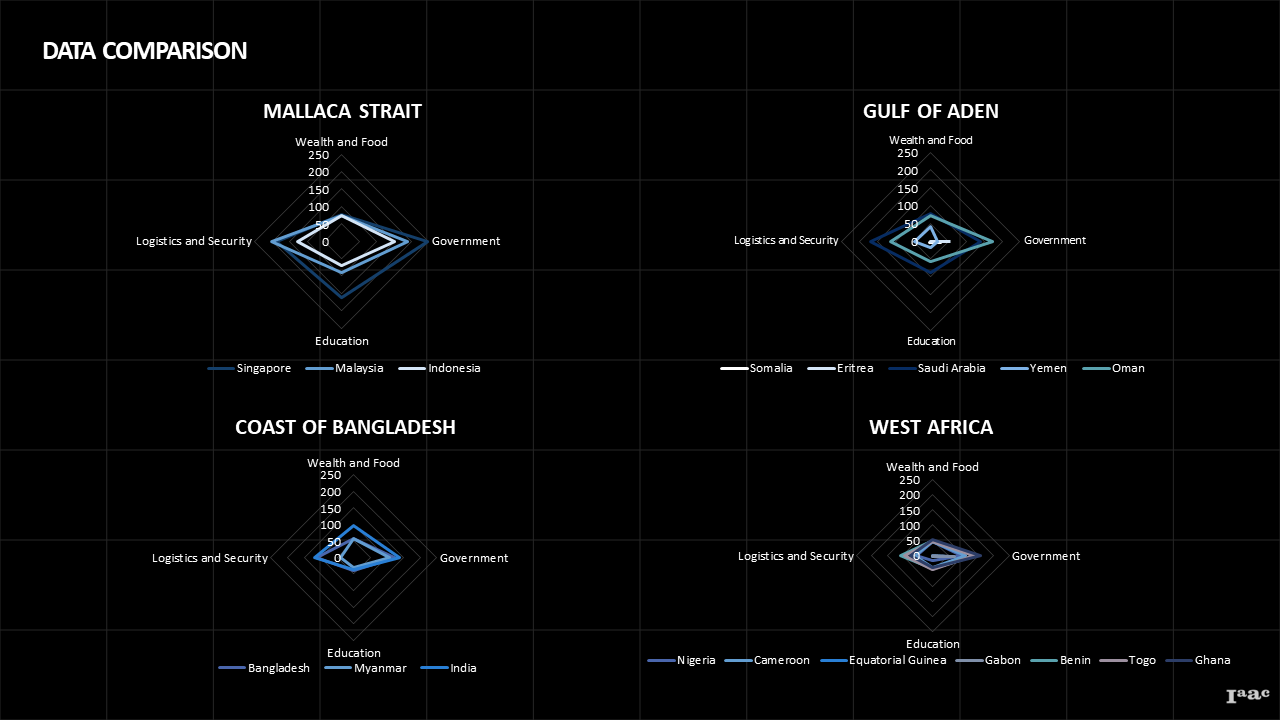

Testing our framework on the known piracy hotspots in the World, it is visible that countries in those regions score low on all pillars. Moreover, by plotting on a spider chart the scores obtained for each country in a region on all of the 4 pillars, we can estimate the country with the highest Piracy Risk Index and evaluate where pirates come from and what areas of interventions in terms of policies are needed. Our framework shows Somalia, Eritrea and Yemen as countries with the highest index in the Gulf of Aden and Malaysia and Indonesia in the Malacca Straits.

4. GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS

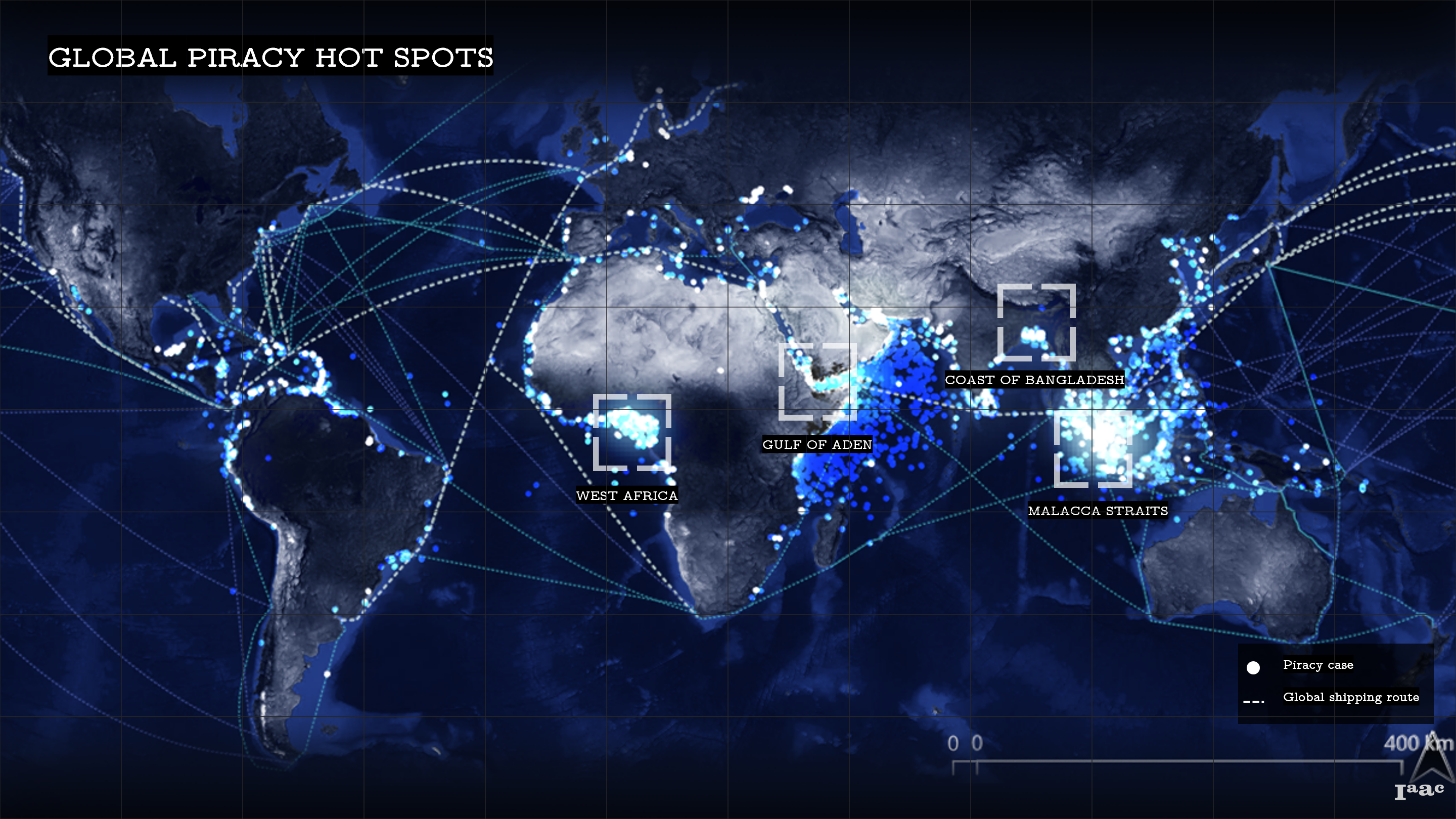

The analysis conducted with data provided by the Maritime Security Organization has brought to light the presence of four main global piracy hotspots. These hotspots, namely the Gulf of Aden, the Strait of Malacca, the Coast of Bangladesh, and West Africa, have shown consistent and alarming levels of piracy activity over the years. By mapping reported incidents and examining historical trends in these regions, we have gained valuable insights into the dynamics of piracy, including its emergence, escalation, and organizational patterns. This information underscores the critical importance of bolstering maritime security measures to address the ongoing threat posed by piracy in these key areas.

GULF OF ADEN

Zooming in on the Gulf of Aden, it becomes evident that pirate attacks are strategically targeted at major global shipping routes. By analyzing the locations of these attacks and the size of pirate crews involved, we were able to estimate the fuel consumption required for their operations. Correlating this data with online reports detailing the destinations of hijacked ships, we successfully identified piracy hotspots—the origin points of pirate activities.

During the period spanning 1991 to 2004, hijackings off the Somali coastline occurred sporadically, with a seemingly random selection of anchorage locations for hijacked vessels. These anchorages included Eyl, Bosaso, Bolimoog, Ras Hafun, Kismayo, Geesaley, Xabo, Bereeda, Bargaal, Garacad, El Maan, Mogadishu, and Barawe. Notably, these anchorages were distributed relatively evenly across the timeframe, with most hosting a maximum of two vessels, except for Eyl (which accommodated four vessels) and Bosaso (which had three).

The majority of hijacked vessels were commandeered by pirate groups operating from Harardhere and Hobyo, located along Somalia’s central South Mudug coastline—an area with no prior history of maritime predation. Harardhere saw the arrival of fifteen registered vessels, while six registered vessels were brought to Hobyo. A smaller number of vessels were taken to Kismaayo (three vessels, all captured in a single attack), Eyl, Xiis (a village in northwest Somalia within the territory of the self-declared independent State of Somaliland), and Barawe.

These urban centers serve as the primary origins for Somalian pirates. By mapping these centers, we can identify the human setlements where targeted policies are needed for implementation. Examples of potential local policy development initiatives could include:

- Wealth and Food:

- Providing incentives for agricultural investment: Implement policies that encourage investment in modern agricultural techniques, infrastructure, and technology to increase agricultural productivity and ensure food security. This could include tax incentives, subsidies for mechanization, and support for agricultural research and development.

- Offering support for microfinance and entrepreneurship: Establish programs to provide microfinance loans and technical assistance to small-scale farmers and entrepreneurs, enabling them to expand their businesses, increase income, and contribute to local economic growth. This can include training in financial management, business skills, and access to markets.

- Government:

- Implementing measures to enhance transparency and accountability: Strengthen transparency and accountability mechanisms within government institutions by implementing measures such as regular audits, public disclosure of financial information, and citizen participation in decision-making processes. This helps to build trust in government institutions and reduces corruption.

- Investing in capacity building and training for government officials: Invest in training programs and capacity building for government officials at all levels to enhance their skills in governance, policy formulation, and service delivery. This ensures effective and efficient public administration, leading to better service provision and governance outcomes.

- Education:

- Developing infrastructure to improve educational facilities: Prioritize infrastructure development in education, including building and renovating schools, providing access to electricity and clean water, and improving transportation networks to ensure all children have access to quality education.

- Providing training and support for teachers: Develop comprehensive teacher training programs focused on pedagogical techniques, subject knowledge, and classroom management skills. Additionally, provide ongoing support and professional development opportunities for teachers to enhance teaching quality and student learning outcomes.

- Logistics and Security:

- Investing in critical infrastructure, such as ports and roads: Allocate resources towards improving transportation infrastructure, including roads, ports, and airports, to facilitate the movement of goods and people within the region. This enhances logistics efficiency and fosters economic development.

- Promoting community policing initiatives and fostering collaboration among local communities: Implement community policing initiatives that involve collaboration between law enforcement agencies, local communities, and businesses to address security challenges effectively. This can include community engagement programs, neighborhood watch groups, and information sharing networks to prevent crime and ensure safety.

MALACCA STRAITS

In the Malacca Strait, a distinct geographical landscape is observed. By correlating information regarding land use, human settlements, and their proximity to the sites of pirate attacks, we can gain deeper insights into the origins of the pirates and the factors that drive their actions. This analysis enables us to better understand the geographical and socio-economic dynamics that contribute to piracy in the region.

In the 1980s and 90s, pirates from various locations converged in the Riau Archipelago, particularly in the city of Palembang on Sumatra. Syaful Rozy emerged as a prominent figure, known as the Robin Hood of the sea, who redistributed the spoils from raided vessels. His actions enabled the financing of mosque construction by the local imam. From their kampung (village) in the archipelago, pirates embarked on journeys to other islands in the Malacca Straits or the South China Sea. Towards the late 1990s and early 2000s, Winang’s gang established themselves near Jemaja, within the Anambas Archipelago. There, they coexisted with local fishermen for several months, scouting and attacking vessels. Subsequently, they returned to the Riau Archipelago before reuniting with their families in Sumatra.

Bintan, situated along the China-India maritime trade route, has a rich history documented in 14th-century Chinese maritime records. These records describe Bintan as one of the islands of the Riau archipelago, inhabited by Malay pirates. During the early Sung Dynasty (960-1127), two to three hundred ships were reportedly used by these pirates to intercept Chinese ships returning from the Indian Ocean. Those who resisted were attacked, and ships were forced back to their harbors. This aggressive piracy activity was well-documented by Chinese historians of the time. Furthermore, Ibn Battuta, an Arabian explorer from the 13th century, also mentioned Riau in his writings. He described encountering armed black pirates emerging from small islands, equipped with poised arrows and armed warships. These pirates were notorious for plundering people but did not engage in enslavement.

Different policies could be developed for Bintan in Indonesia to address various challenges and improve overall governance, education, and logistics and security. These policies could aim to decrease corruption, enhance access to education, and bolster infrastructure and safety measures. Below are some proposed policy initiatives:

- Government:

- Decentralization and Empowerment: Implement decentralization policies to empower local governments in Bintan, granting them more authority and resources to address local needs efficiently. This could involve delegating decision-making powers, budgetary allocations, and service delivery responsibilities to the local level, thereby increasing responsiveness and accountability.

- Anti-Corruption Measures: Strengthen anti-corruption measures by establishing independent oversight bodies, enforcing strict ethical codes for public officials, and promoting transparency in government procurement processes. This helps to combat corruption, improve public trust, and enhance the effectiveness of government institutions.

- Education:

- Enhanced Access to Quality Education: Ensure equitable access to quality education by investing in the construction of schools. Additionally, provide incentives such as scholarships, subsidies for school supplies, and transportation assistance to encourage attendance and retention.

- Curriculum Enhancement and Vocational Training: Revise the curriculum to align with the needs of the local economy and global trends, integrating vocational training programs that equip students with practical skills. Collaborate with businesses and technical institutions to develop specialized training courses that prepare students for employment opportunities.

- Logistics and Security:

- Infrastructure Development: Prioritize infrastructure development projects to improve transportation networks, including roads, bridges, and ports, to facilitate the movement of goods and people and enhance connectivity with mainland Indonesia. This supports economic growth and trade.

- Maritime Security Enhancement: Strengthen maritime security measures through increased patrols, surveillance, and collaboration with relevant authorities to combat piracy, illegal fishing, and other maritime crimes. This ensures safety for maritime activities and protects the region’s resources.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we would like to point out 3 fundamental aspects:

1. Fixing piracy would fix quality of life. Using this framework to analyze and develop policies to combat piracy through non-military means for countries that are at risk would also increase the quality of life in those countries.

2. Context is needed for better policy implementation. Analyzing the roots of piracy events and going in depth with geographical analysis would allow for a better understanding of piracy and pirates in general, that would contribute to better policy targeting and an increased possible rate of success.

3. There are no excuses. We unequivocally believe that there exists no justification for inaction in the face of maritime piracy. The resources and capabilities necessary to combat this scourge through non-military means are within reach of nations worldwide. As stewards of maritime security, it is imperative that we leverage the tools at our disposal to safeguard the integrity of global shipping routes and protect the lives and livelihoods of seafarers and communities reliant on maritime trade.

We extend an open invitation to all stakeholders, urging them to embrace our framework as a tool in the ongoing battle against piracy. By harnessing the insights from our research, nations and international organizations alike possess the opportunity to anticipate and preemptively address piracy threats with targeted policies grounded in non-coercive strategies.

If we can envision a different approach, governments can revolutionize it. Our origins as students navigating the complexities of maritime security serve as a testament to the attainability of this mission. If two individuals armed with dedication and ingenuity can propose solutions, we harbor unwavering confidence in the collective capacity of governments and international bodies to rise to the challenge. Let us unite in our commitment to a future free from the specter of maritime piracy, where the seas remain pathways of prosperity and unity for all nations.