AI in the Anthropocene

The architectural profession is currently at a critical juncture, faced with the dual challenges of advancing artificial intelligence (AI) and the escalating climate crisis. Many architects harbour fears of obsolescence as AI’s capabilities expand, potentially automating tasks that traditionally require human expertise. This concern is not unfounded, as AI-driven tools increasingly demonstrate their capacity to handle complex design and analytical functions within the architectural domain (Barker, 2023) (Leach, 2023).

Historically, architecture has been profoundly influenced by human-centric paradigms. Since the time of Vitruvius, whose principles have long shaped the profession, architectural theory has emphasized human proportions and needs, often to the detriment of broader ecological considerations. Vitruvius’ work, particularly his treatise “De Architectura,” laid the groundwork for a discipline that views human beings as the measure of all things, thus perpetuating a built environment prioritising human dominance over nature.

However, the urgent realities of climate change are forcing a reevaluation of this perspective. The increasing frequency and severity of human-wildlife conflicts, driven by habitat loss and environmental degradation, underscore the necessity for a more inclusive approach to design (Natucate, 2021) (WWF, 2021). Within this context, AI emerges as a potential disruptor and a facilitator for new interaction and co-design between humans and the natural world. By leveraging AI, architects can develop solutions that foster harmonious coexistence and address the needs of all species involved (Leach, 2023).

Interspecies design shifts the focus from human-centred approaches to considering the entire biosphere. This method acknowledges the agency of non-human species, fostering a participatory design process that includes diverse biological insights. Examples include projects that create bird-safe urban windows and emergency food sources for city-dwelling insects, highlighting the potential for AI to mediate between species and design environments that benefit all inhabitants (Unbore, 2021).

There is, therefore, a compelling need for a new philosophical framework within architecture. Moving beyond the entrenched notion of human exceptionalism, architects must embrace a post-humanist perspective that acknowledges the interconnectedness of all life forms. Such a shift necessitates a fundamental change in how we conceive, design, and interact with our built environment. By adopting this holistic and ethically inclusive approach, architects can create sustainable and conducive spaces for the well-being of both human and non-human inhabitants. This new direction not only responds to the immediate threats posed by AI and climate change but also redefines the role of architecture in fostering a balanced and resilient future for all.

By revisiting and revising the foundational philosophies that have historically guided architectural practice, we can move towards a future where the profession survives and thrives, contributing to a more equitable and sustainable world.

Integrating contemporary philosophical perspectives, such as Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) and flat ontology, into architectural practice can significantly influence this new paradigm. OOO challenges anthropocentrism by positing that all human and non-human entities possess equal ontological status. This approach encourages designers to consider non-human objects’ intrinsic value and agency, promoting a more inclusive and equitable framework (Ssanter, 2020). By treating all entities with equal importance, flat ontology helps dismantle hierarchies and biases, fostering a more holistic understanding of the interconnectedness within ecosystems (Ssanter, 2020).

“What we architects should be designing right now is not another building, but rather the very future of our profession” – Neil Leach

Architects are responsible for pioneering a new ethos that prioritizes ecological balance and ethical inclusivity. This involves utilizing AI technologies to create more adaptive and responsive designs, encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration, and continually challenging and evolving the profession’s underlying values and assumptions.

More-than-Human Intelligence

We seek frameworks for a broader definition of intelligence. In James Bridle’s recent book, “Ways of Being”, he points out that “…understanding intelligence as being both embodied and relational has implications for us. It is for humans to meet other humans and for cultures to meet different human cultures. It has implications for our relationship with other nonhuman species of all kinds––animals, plants, ecosystems, that I say, and it also has implications for machine intelligence as well––that we start to think of, particularly artificial intelligence is not being just a different or lesser or form of human intelligence, but really another type of intelligence arising in the world that is as interesting or not as any other kind.” [1] https://forthewild.world/podcast-transcripts/james-bridle-on-modes-of-intelligence-343

Closely tied to this is the idea of umwelts and that other species and machines have an umwelt often inaccessible to humans – or at least, not entirely understandable. Umwelt is a term coined by Jakob von Uexküll that essentially refers to worlds of subjective experience. [2] “Jakob von Uexküll’s Concept of Umwelt” by Tim Elmo Feiten (Keywords: Biology; Metaphysics; Animals) (thephilosopher1923.org)

“The structure of this world is largely determined by the species to which a creature belongs, by its physiology, its behaviour, and its environment, but this world discloses itself only through individual subjective experience. These worlds are both private and unique to each living subject.” [2]

Perhaps there is wisdom in recognizing AI’s umwelt. One example of this general notion is that of Asunder, by Tega Brain, Julian Oliver, and Bengt Sjölén. As described by Zeilinger [3], Asunder presents itself as an AI-driven “environmental manager” that generates recommendations for terraforming interventions based on its evaluation of a wide range of “satellite, climate, topography, geology, biodiversity, population and social media data” (Debatty 2019) gathered in real-time. Furthermore, we may dismiss what the AI model recommends when viewing the work. Referring to the notion of AI as a hyperobject – a term coined by Timothy Morton – Zeilinger once again advises:

“Indeed, it is easy to rationalize the absurdity/ impossibility of the AI suggestions by foregrounding AI’s non-human-ness as an insurmountable obstacle that prevents the system from recommending meaningful changes…But what is inevitably lost in such a rationalization is an appreciation of the seemingly beyond-human enormity of the changes that are now required to counteract global warming…In other words, to interpret the artwork’s AI system as incompetent or nonsensical from a human, anthropocentric perspective obstructs one’s view of the vast, almost unthinkable scale on which human activity now impacts the planet.”[2]

Finally, the Earth Species Project (https://www.earthspecies.org/) directly leverages what we’ve learned from human language and our AI models, this time pointing the machine towards non-humans. They are decoding other species’ communication utilizing AI in a more-than-human spirit, building awareness and empathy in a world quickly losing biodiversity.

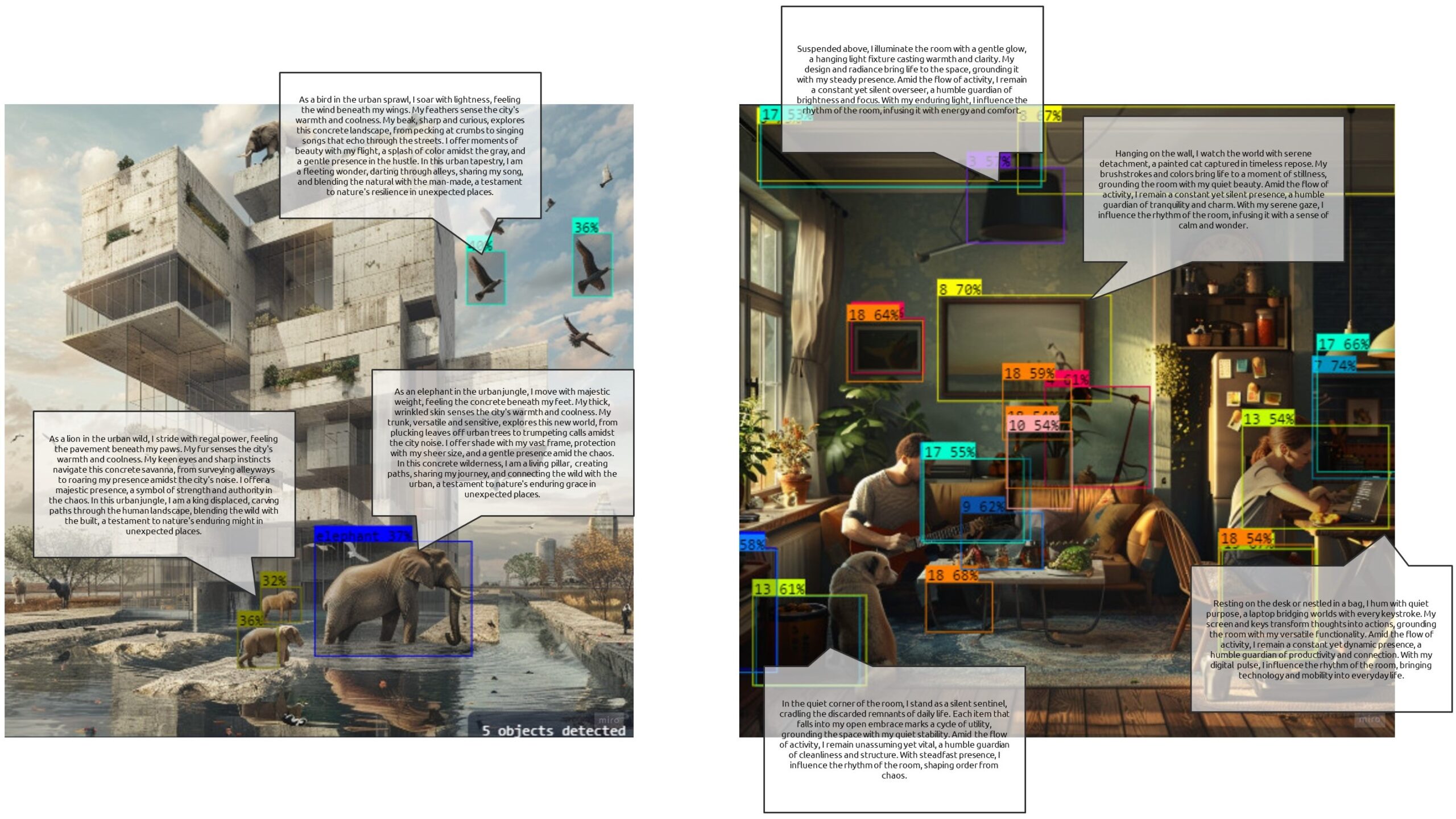

Speculative AI

As a first thought experiment, we had Midjourney generate an image of animals and household objects; next, a computer vision model detects and labels the animals and objects. ChatGPT was prompted to take the position of the animals and objects, talking about their phenomenological experiences and affordances to architecture and to the other objects in the living room. This rather simple methodology implies human and AI collaboration to try and access animal and object umwelts.

New Perspective

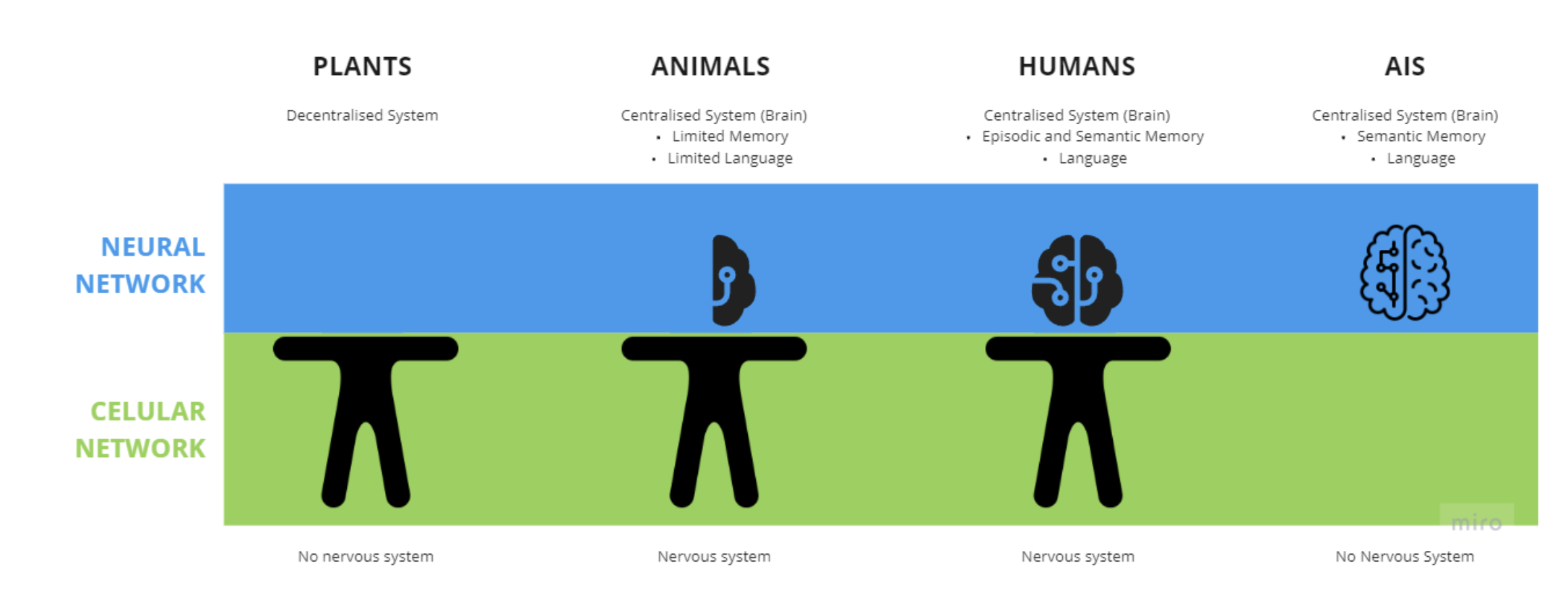

We are well on our way to a communication channel with beings with artificial neural networks that have access to language to encode and decode large amounts of information. But how about channels to communicate with mammals that rely on a centralised neural network but with more straightforward or no existing language (aka recursiveness)? How about communication channels with beings like plants that, while still embodied, lack a neural network? Intelligence is definitely not limited to electrical neural networks. To explore some of these questions, we gave ChatGPT 4o the entire manuscript of Manuel Delanda’s “Philosophy and Simulation” and interrogated it about non-human intelligence.

What data should be collected and encoded from these other inhabitants of our planet? The Delandian GPT answered that we could collect physiological and behavioural features that could be registered and encoded via sensors, computer vision, and time-lapse imaging.

When questioned about what it would take to train an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) for the non-human, it suggested paying attention to changes in leaf angles that might indicate water stress or keeping mobile devices handy to keep continuous communication with plants. It also meant a mapping system that translates specific bark patterns into an “I am hungry”, for example.

To conclude the interrogation, our synthetic Delanda concluded that such a system could help species express their needs clearly and efficiently: plants can tell when they need light or water, while dogs could finally understand what their owner has been trying to communicate via comprehensible signals.

Jokes aside, it is an excellent exercise to remind oneself of different communication systems and the limitations or excesses that each system entails.

Manifesto

We created a manifesto in collaboration with AI. All images are generated using Midjourney, and the text is generated by an LLM (Mistral) built with a custom RAG (with access to texts from Tessa Leach, Joanna Zylinska, Ahmed Ansari and research papers by Michael Levin). The idea is to leverage other intelligences to address the challenges of our time.