History is not always written in neat paragraphs and grand monuments. Sometimes, the most important stories are the ones left untold. The ones silenced, forgotten, or deliberately erased. In 1994, over a period of 100 days, the Rwandan genocide took place. Hutu extremists; fueled by ethnic hatred and political manipulation, sought to eradicate the Tutsi minority. As a result, millions were displaced, and families torn apart.

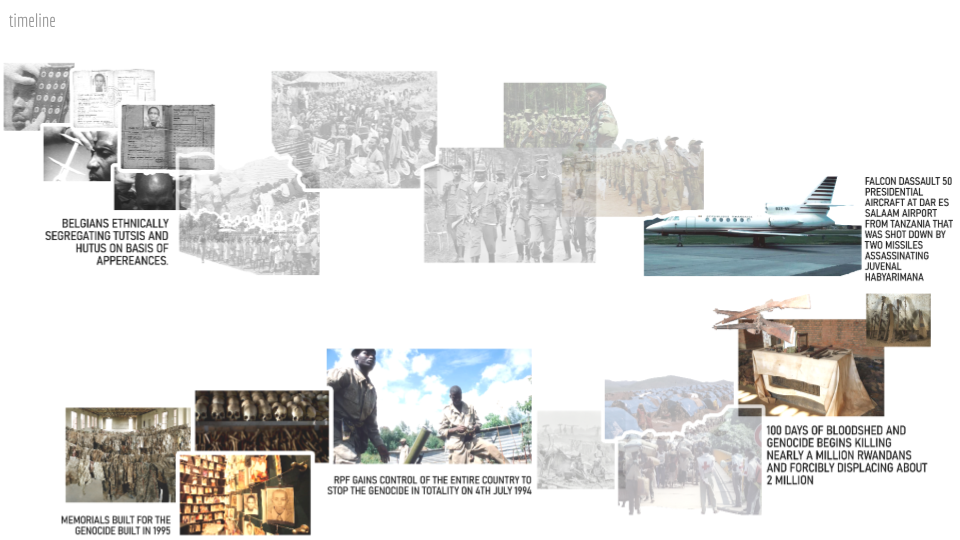

An overview of the genocide

Accounts of the genocide suggest that it was not a sudden occurrence, but a culmination of simmering ethnic tensions. The introduction of ethnic identity cards during the Belgian colonial rule, further hardened these lines and is widely believed to be the reason for the conflict. The 1990’s saw a rise in these tensions, culminating in the assassination of President Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu leader, in 1994. This sparked a chain reaction that led to the genocide.The Rwandan Patriotic Front, a group of exiled Tutsi, eventually pushed back, forcing an end to the genocide in July 1994

The genocide sent shock waves beyond it’s borders causing regional destabilization in Burundi and The Democratic Republic of Congo due to the displacement of people. Here, mobility and conflict become entangled, feeding off each other in a devastating spiral. This interdependence is not a linear cause-and-effect relationship; which requires alternate methods of storytelling, research and archiving in order to fully understand the breadth , depth cause and relationships of seemingly tangential issues of the conflict.

The question of this study then becomes what are the systemic issues of designing after an intent to erase the existing ?

Method

This study used two main approaches:

- Mapping Colonial Control: We analyzed historical German and Belgian colonial maps of Rwanda to understand how they established power and control over the region.

- Mapping the Genocide Narrative: We studied how the Rwandan genocide is presented in various sources (literature, media, etc.) to see what themes are emphasized and who controls the storytelling.

- Temporal Analysis : We created a timeline using the information we gathered. This timeline serves two purposes: it visually records the events of the genocide, and it helps us analyze and understand the event as a whole.

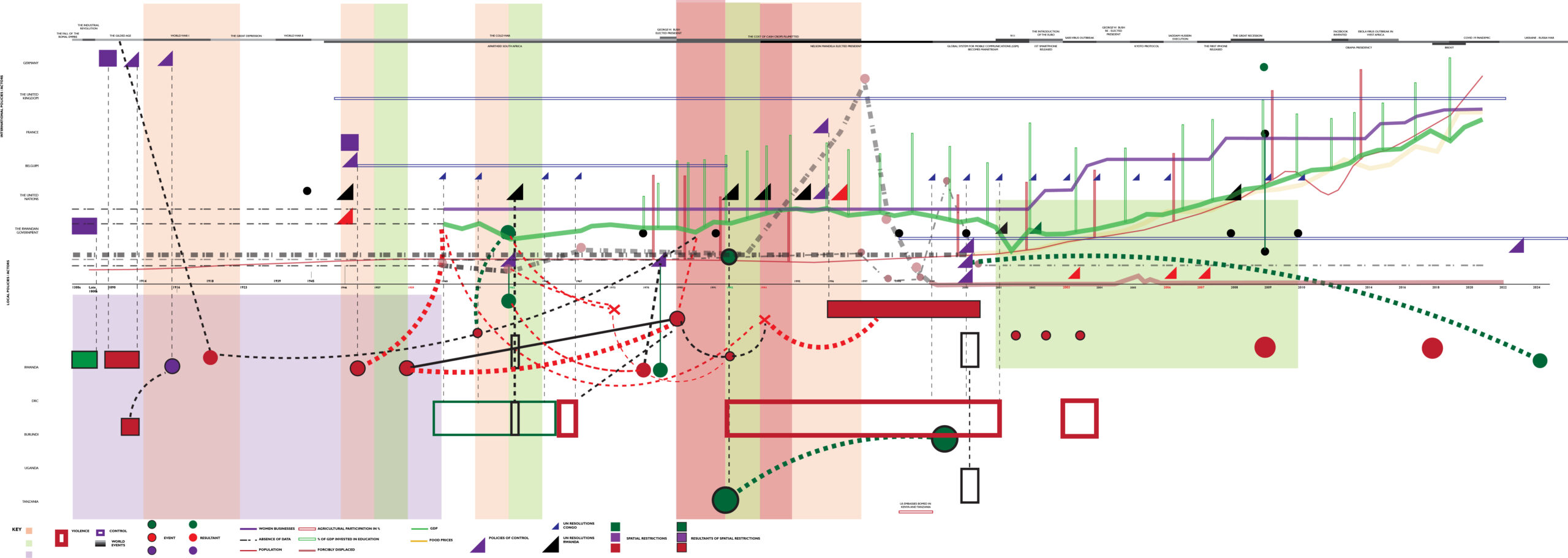

The Timeline

Diagram Symbology

As a general note, these colours represent the following on the map:

- Purple: Control

- Black: Neutral

- Green: Positive

- Red: Negative, Tension, Violence

- Background Bands:

- Green : Periods of release

- Red & Peach : Periods of tension

- Purple: Period of colonial rule

- Axes:

- X-axis : Time

- Y-axis : Actors. The ‘influencers’ are listed on the top half and the ‘influenced’ on the bottom half.

- Lines: Lines (green, purple, etc.) represent statistics like GDP, population, etc.

- Red: Population

- Green: Gross Domestic Product

- Yellow: Food prices

- Peach: Forcibly displaces

- Triangles: Policies enacted nationally and internationally

- Rectangles:

- Rectangles: Spatial Constraints

- Black outlined squares: Consequences of spatial constraints

- Circles:

- Black outlined circles: Events

- Circle: Consequences

- Dashed Lines:

- Straight lines: Simple relationships

- Curved green lines show positive relationships, and curved red lines show negative relationships.

- X’s: targeted killings of important political figures.

- Thick Dash-Dot Line: missing or inaccessible data

Cartographic Regression

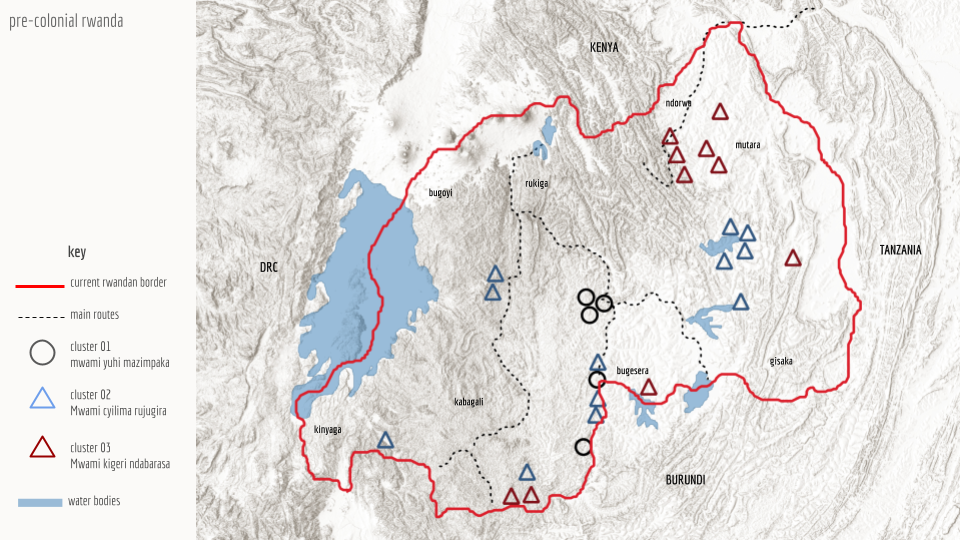

Settlement Patterns in pre – colonial Rwanda

- Topography & Environment

- Land and Water: In pre-colonial Rwanda, fertile valleys and plateaus were prime locations for settlement. These areas provided the rich soil and reliable water sources essential for agriculture, the backbone of Rwandan society.

- Fortified Settlements: Security was also a major concern. Some communities strategically built fortified settlements on hilltops, offering a clear view of the surrounding landscape for spotting potential threats. Alternatively, they might build dwellings within enclosures for added protection.

- Lake Kivu’s Shores: Settlements around Lake Kivu flourished thanks to the lake’s bounty. Fishing provided a steady food source, while the water itself served as a vital trade route connecting Rwandan communities with others in the region.

- Mixed Farming Strategies: Rwandans practiced mixed farming, raising livestock alongside growing crops. This dual need for land influenced settlement patterns. Villages would often be situated near areas offering a combination of fertile land for crops and grazing pastures for animals.

- Social Structure and Kinship

- Centralized Villages: Many Rwandans lived in nucleated settlements, clustered villages organized into chiefdoms led by a Mwami (king). These villages often grew around the homes of clan leaders or followed extended family lineages, fostering a strong sense of community.

- Scattered Homesteads: Near valuable resources like grazing lands or natural resources, settlements became more dispersed. Individual homesteads dotted the landscape, allowing residents direct access to what they needed.

- Following the Seasons: Some groups practiced seasonal movement. Herders might migrate their livestock to different pastures throughout the year, while farmers shifted their homesteads based on agricultural cycles, ensuring optimal use of the land.

Physical Forms of Control in Colonial Rwanda

- New means of transportation & transportation routes:

- German colonizers envisioned the circulation of pack animals, carts, and potentially automobiles on their roads.

- Starting from 1904, construction of state roads and sections of the central caravan route to accommodate year-round traffic with carts began.

- Establishment of Marketplaces: Efforts were made to attach some of the new roads to the needs of caravan travel by forcing entire groups to resettle along the highways. These marketplaces served as points for trade between settlers and caravan travelers.

- Forts and Outposts:

- Strategic locations were fortified with military installations to deter rebellions and control key trade routes and communication networks.

- Askari: They recruited local soldiers, known as Askari, to supplement their forces. These troops, while not always fully loyal, provided additional manpower and knowledge of the local terrain.

- Telegraph Lines: Communication infrastructure like telegraph lines helped maintain control and coordination between different regions.

Data Limitations : Data on the specific geographic distribution of ethnic groups, especially pre-colonial, is scarce and potentially unreliable. Colonial records often focused on administrative divisions rather than detailed ethnic mapping

Non – Physical Forms of Control

- Administrative:

- Indirect rule where they utilized existing local hierarchies and appointed chiefs loyal to the German administration.

- Direct rule where they appointing German officials to govern local populations

- Economic:

- They established large plantations for cash crops like coffee and cotton, exploiting local labor and resources for their economic benefit.

- They imposed taxes on various economic activities and established monopolies on specific goods to control trade and generate revenue.

- Cultural Assimilation: Established schools where German & French language and culture were taught, aiming to create a loyal and compliant population

- Social Engineering:

- Racial categorization where they introduced a system of racial classification, solidifying the social hierarchy by identifying Tutsis as a “superior race” and Hutus as an “inferior race.” This policy exacerbated pre-existing tensions and planted the seeds for future conflicts.

- Education: The colonial education system primarily served to train individuals for specific roles within the colonial hierarchy, promoting obedience and discouraging critical thinking or questioning of Belgian authority.

- Religion: churches were established in key locations to convert local populations to Christianity.

Economic Vulnerability and Decline

Rwanda’s pre-genocide economy was heavily reliant on coffee and tea exports, employing a staggering 90% of the workforce and contributing 60% of GDP. Despite this agricultural focus, Rwanda remained a poor nation (GDP per capita $270 in 1990). The economy was vulnerable to external shocks like coffee price drops and heavily reliant on foreign aid, especially during times of conflict. Droughts in the 1980’s further exacerbated a decline fueled by falling coffee prices and government mismanagement. Understanding these vulnerabilities and external pressures provides context for Rwanda’s economic landscape before, during and after the genocide.

Literature Mapping

This study analyzed 150 scholarly articles on the Rwandan genocide retrieved from Google Scholar. The analysis revealed three prominent themes: post-colonial studies, sexual violence, and central factors contributing to the genocide. Interestingly, 70% of the articles originated from the UK (38%) and the US (32%), with a smaller contribution from the Netherlands (20%).This distribution hints at who may be leading the conversation about the genocide and the language used to frame the narrative.

Conclusion

Creating a comprehensive archive empowers design professionals and policymakers. It allows them to critically analyze historical, cultural, and political factors surrounding the genocide, leading to more informed decisions.

Future Study

- Deepening Literature Analysis:

- Keyword Extraction: Further analysis of the identified themes is needed to extract key keywords.

- Author Origin: Mapping the authors’ nationalities can help understand why stories are told in certain locations.

- Plot these keywords on a timeline alongside historical events to understand how narratives connect to the genocide.

- Research the long-lasting consequences of the genocide on Rwandan society today.

References

- Human Rights Watch (1994). Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda. https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/1999/rwanda Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- UNHCR (The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) (2020). The Links Between Forced Displacement and Conflict. https://www.unhcr.org/news/unhcr-forced-displacement-continues-grow-conflicts-escalate Retrieved March 25, 2024.

- Vansina, J. (2004). Rwanda under colonial rule, 1908-1960. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Prunier, G. (1995). The Rwanda crisis: History and background. London: Hurst & Co.

- Smith, J. (2023, March 10). The War of Legs: Transport and Infrastructure in the East African Campaign of World War I.

- Lemarchand, R. (1970). Rwanda and Burundi. London: Pall Mall Press.

- Newbury, D. (n.d.). Precolonial Burundi and Rwanda: Local Loyalties, Regional Royalties.

- Expat East Africca. Mapping Rwanda. https://expateastafrica.com/home/kigali/mapping-rwanda/ Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACLED). (2017, January 1 – present). ACLED All Africa Data [Data set]. UNDP. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (n.d.). Human Development Indicators for Rwanda [Data set].Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (n.d.). FAOSTAT – Food Prices (Rwanda) [Data set].Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- World Population Data (WPD). (2023). WPDx RW [Data set]. https://data.humdata.org/dataset/wpdx_rwa.Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- World Bank. (2019). World Bank Trade Indicators for Rwanda [Data set]. https://data.humdata.org/dataset/world-bank-trade-indicators-for-rwanda.Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- World Bank. (2019). World Bank Gender Indicators for Rwanda [Data set]. https://data.humdata.org/dataset/world-bank-gender-indicators-for-rwanda.Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- World Bank. (2019). World Bank Poverty Indicators for Rwanda [Data set]. https://data.humdata.org/dataset/world-bank-poverty-indicators-for-rwanda.Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- World Bank. (2019). World Bank Health Indicators for Rwanda [Data set]. https://data.humdata.org/dataset/world-bank-health-indicators-for-rwanda.Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- World Bank. (2019). World Bank Agriculture and Rural Development Indicators for Rwanda [Data set]. https://data.humdata.org/dataset/world-bank-agriculture-and-rural-development-indicators-for-rwanda.Retrieved March 17, 2024.