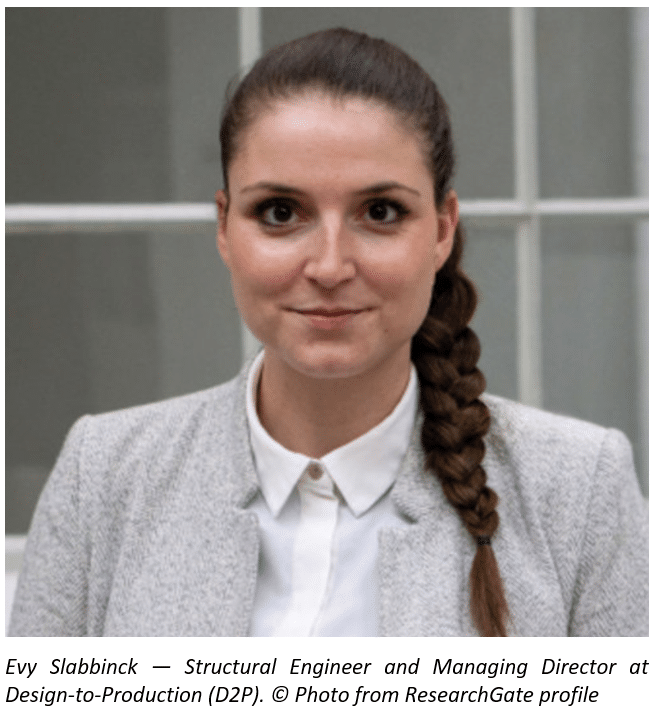

Evy Slabbinck – D2P – Design to Production

How do you build a complex timber structure with zero errors in record time? Evy Slabbinck from Design-to-Production reveals the answer: merging computational precision with material intelligence. In this interview, we explored bending-active design, digital fabrication workflows, and the philosophy behind projects that push timber to new architectural limits while staying environmentally responsible.

Evy Slabbinck, a structural engineer specialized in timber and complex geometry, presented insights from her work at Design-to-Production (D2P), a Swiss company bridging digital design and fabrication in advanced timber architecture. With a background from Stuttgart’s ICD/ITKE, she focuses on bending-active structures that exploit wood’s natural flexibility to create lightweight, expressive forms. D2P’s interdisciplinary approach merges architecture, engineering, and programming through three departments: digital planning, timber consulting, and software development. The firm’s portfolio includes iconic projects like Centre Pompidou Metz, Cambridge Mosque, and Swatch Headquarters, demonstrating how computational design pushes timber to new architectural limits.

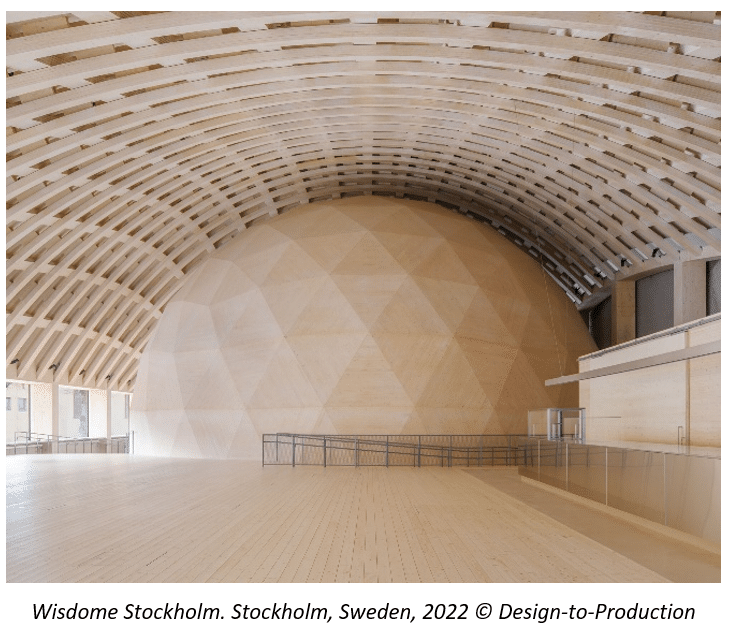

The presentation emphasized wood’s anisotropic properties and engineered products like CLT, Glulam, and LVL that enable efficient use of smaller trees. D2P’s methodology considers eight key aspects: design intent, engineering, materials, interfaces, production, logistics, pre-assembly, and installation. The case study focused on Wisdome Stockholm, completed in 1.8 years with just three people assembling the structure. All timber pieces were CNC-cut flat and bent on-site, achieving zero production errors through extensive mock-up testing. The project proved that merging digital precision with material intelligence creates construction that’s both technologically innovative and environmentally responsible.

In Conversation with Evy Slabbinck

Does the digital workflow truly connect architectural intent to fabrication files, or does it still require constant remodeling as it did years ago?

The digital workflow functions effectively, but D2P never uses architects’ models—they always start from scratch, extracting design rules rather than inheriting potential errors. Wisdom Stockholm’s success came from early project involvement, before procurement, avoiding the typical scenario where everything gets discarded post-procurement. A critical factor was the architects implementing an early design freeze. Fundamental late changes require reprocessing entire model sequences. This project achieved unprecedented success: zero production errors compared to typical projects with minor mistakes. The hierarchical model stack (context, reference, coordination, detail, production) worked seamlessly once each layer was finalized.

What happens to large-scale mockup materials after testing? Are they recycled or reused for smaller projects?

Physical mockups are not recycled. Blumer Lehmann maintains a complete warehouse of mockups serving as their marketing showcase. Mockups sometimes get shipped to clients for display in their buildings or placed in museums. The mockups function as demonstration pieces and portfolio evidence rather than being repurposed or recycled into other projects. While sustainability is important in actual construction, these full-scale prototypes serve ongoing value as physical references of innovative construction methods and completed projects.

You don’t use traditional BIM or Grasshopper but have custom Python tools. How do these scripts integrate, and where does digital fabrication happen in your workflow?

D2P practices Building Information Modeling but doesn’t follow traditional BIM standards. They use Python directly in Rhino without Grasshopper for large projects. Their proprietary component library operates faster with more capabilities than Grasshopper, though the principles remain similar—just pre-programmed. DTP Components (publicly available on Food4Rhino) demonstrate their hierarchical modeling approach where crossing components automatically generate joints. The system is equally capable as Grasshopper but optimized for complex timber projects. Educational webinars explaining their methodology are available on Rhinoceros’ YouTube channel.

What is your perspective on Building Information Modeling and its role in timber construction?

BIM serves important roles in construction standardization and reducing errors, making professionals think structurally about buildings. However, D2P questions whether current BIM approaches are optimal. A memorable quote from Paul (ICD, 10 years ago): “What’s the point of modeling every toilet roll?” Their philosophy: models should evolve according to specific needs at different project stages. Fabrication models need only CNC-required information. Digital twins for maintenance come afterward, handled by BIM specialists. No single 3D model should exist—instead, code should generate stage-specific models. BIM standardizes process, not design.

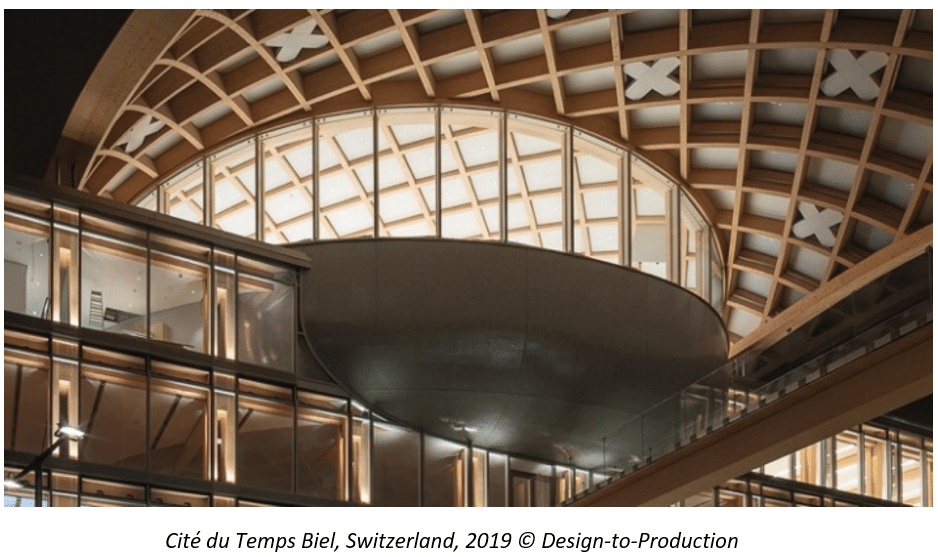

In some of D2P projects, it uses hexagonal pattern. What are the advantages of the hexagon in terms of stress distribution?

The hexagonal design originated from architect Shigeru Ban, who has strong timber expertise. Structurally, the pattern creates compression arches between columns, functioning like table legs with arching connections. Initial concerns about horizontal stability for the 14-meter glass facade proved unfounded—calculations confirmed complete stability. Wood anchors tie columns together. The hexagonal pattern incorporates triangles, which are structurally optimal. The dense pattern effectively controls horizontal movement. While the hexagon came from architectural intent, it proved structurally beneficial, eliminating the need for additional facade stabilization.

How do you consider the anisotropy of wood materials when designing complex curved structures?

Anisotropy is addressed at multiple scales. For blanks, fiber cutting angles are optimized and communicated to engineers for calculation adjustments. Globally, fiber continuity is maintained throughout designs—easier in complex curved structures than orthogonal buildings. In orthogonal beam-column connections, forces traveling perpendicular to grain (worst direction) create problems. The solution: maintain continuous fiber in columns and use reinforced hardwood elements to transfer forces through shear when fiber direction interrupts. The approach: follow fiber globally, then resolve each detail and element locally based on fiber cutting angles.

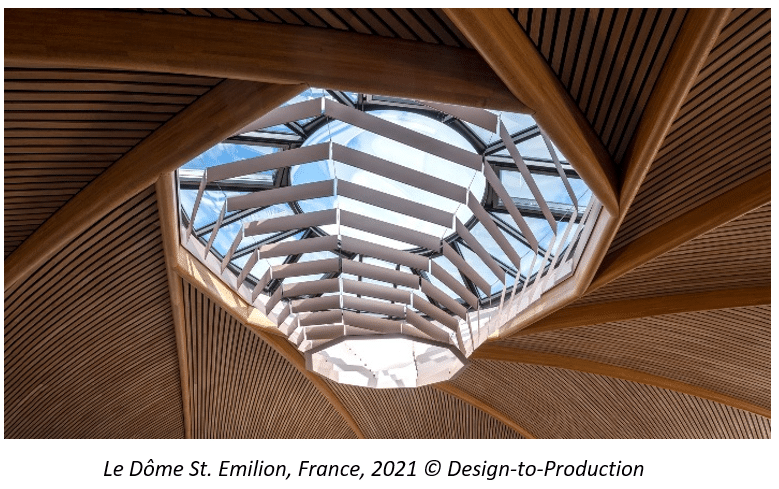

What is the relationship between software tools and craftsmanship in contemporary wood construction, and where do you see the greatest opportunities for technological advancement?

The discussion focused on arrays and lamination techniques used in projects like Cambridge Mosque and Shigeru Ban’s work. While craftsmanship is valued, the future points toward construction standardization—not design uniformity—to reduce costs and environmental impact. Construction remains expensive because each building is essentially unique. Using the automotive industry as an analogy: if every car were custom-built, it would cost as much as a house. Standardization enables dramatic cost reduction and material efficiency while maintaining individual satisfaction. The key is standardizing how we build, not what we build.

How do fiber strengths influence the future of wood construction, and are designs ultimately limited by inherent wood fiber strength?

New products like BauBuche achieve 75 MPa compressive strength (comparable to concrete) versus typical spruce glulam at 24 MPa. Beyond off-the-shelf products, Design-to-Production designs custom materials—CLT structures incorporating hardwood reinforcements where standard CLT is insufficient. Hardwood fibers are aligned according to specific structural force directions, creating visual contrast that becomes a design feature rather than something to hide. The philosophy: use the right material in the right place, including steel or concrete when appropriate, rather than limiting designs to single materials.

Where Code Meets Construction

The work of Evy Slabbinck and Design-to-Production demonstrates that the future of timber construction lies at the intersection of computational precision and material intelligence. By integrating digital workflows with deep understanding of wood’s properties, complex architectural visions become buildable realities—proving that innovation and sustainability can advance together. We extend our sincere gratitude to Evy Slabbinck for sharing her expertise and insights with us, and to Design-to-Production for their continued contributions to advancing sustainable architecture through digital innovation.