For the Love of Pasta

Introduction: From Your Dinner Plate to Architectural Design

Look closely at a piece of pasta. The curves, ridges, and hollows aren’t just for holding sauce; they are feats of structural engineering in miniature. But could the mathematical logic behind a common pasta shape be scaled up to create a full-sized, human-scale building? It’s a question that moves design from the culinary to the computational, from the kitchen to the construction site.

This isn’t just a thought experiment. In a student project called the “Cappelletti Pavilion,” Ahmad Baltaji and Emilie El Chidiac did exactly that. They took the precise formula for a piece of Cappelletti pasta and used it as the genetic code for a complex architectural structure. The project followed a clear four-phase journey: from backstory and form-finding to optimization and visualization, revealing fascinating insights into the future of design.

This article explores the four most surprising and impactful takeaways from their process of turning a pasta formula into a full-scale pavilion. From literal recipe-to-blueprint translation to AI-driven evolution, their work offers a glimpse into a new way of thinking about building.

1. A Recipe Can Literally Become a Blueprint

The Cappelletti Pavilion project began not with a sketch, but with a recipe. In the initial “Backstory” and “Form Finding” phases, the goal was a “direct digital translation from plate to pavilion.” The idea was not to simply be inspired by the pasta’s shape, but to use its fundamental mathematical description as the starting point for the architectural form.

Sourcing the parametric equations (a way of defining a shape using mathematical variables) for Cappelletti pasta from the book Pasta by Design, students Ahmad Baltaji and Emilie El Chidiac used a Python script within the Grasshopper visual programming environment to generate a 3D model. However, they didn’t just enlarge the formula. In a key act of practical design, they cut and scaled the shape to fit within an 8x8x6 meter bounding box, ensuring the spatial flow made sense for human experience. To give the surface its structural bones, they then used a tool called Crystallon to generate an initial lattice structure, creating the pavilion’s wireframe skeleton.

Welcome to the Cappelletti Pavilion where we decided to scale up dinner and turn pasta into a pavilion.

2. The Best Design Was “Evolved,” Not Just Drawn

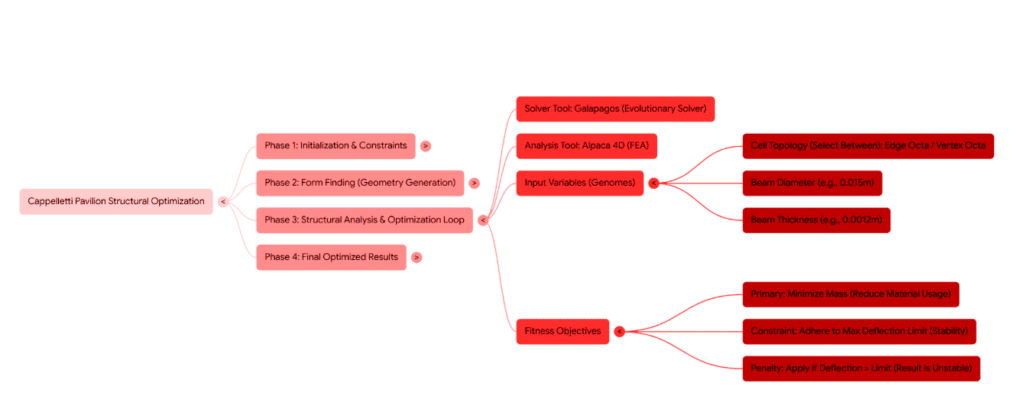

Here’s where the project pivots from mere translation to true innovation. In the project’s third phase, optimization, the team moved beyond simple translation, implementing an “evolutionary feedback loop” to discover the most efficient design possible. Instead of relying on human intuition, they let an algorithm mimic natural selection to “evolve” a better structure over thousands of generations.

Using a tool called Galapagos as the “evolutionary solver” and Alpaca 4D for Finite Element Analysis (FEA, a method for simulating physical forces on a digital model), the system tested countless structural variations. The objective was clear: ensure stability while minimizing material usage. The solver was allowed to mutate three core “genomes” of the design: the cell topology (the geometric pattern of the lattice), the beam diameter, and the beam thickness. This method allows a computer to explore a vast landscape of potential solutions, often discovering highly optimized and non-obvious designs that a human might never conceive of through traditional methods.

3. A Single Shape Required Two Different Structural Solutions

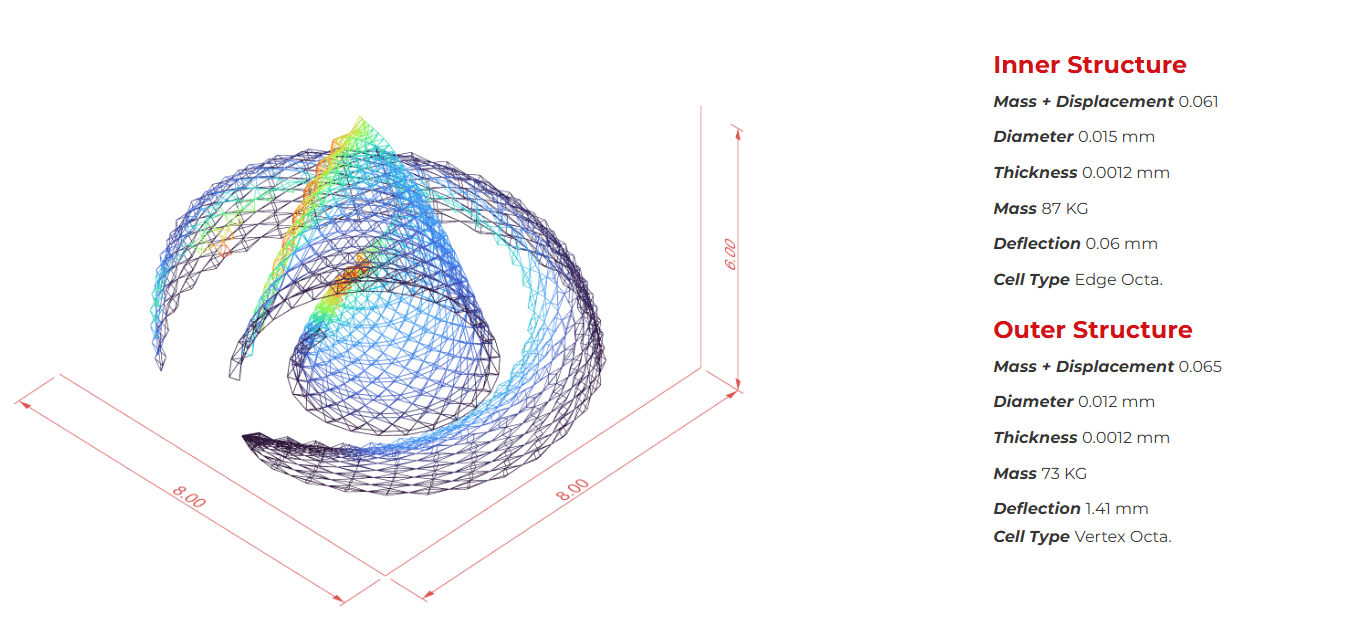

One of the most profound results from the evolutionary process was that the algorithm arrived at two different optimal structures for the pavilion’s inner and outer shells—even though they are part of a single, continuous shape.

The solver discovered that the forces acting on the outer shell were best handled by a lattice with a “vertex octa” topology. The inner shell, however, required a completely different “edge octa” configuration to achieve the best performance. This is a prime example of computational design uncovering non-intuitive solutions that would be nearly impossible for a human to intuit. It’s a powerful demonstration that a one-size-fits-all approach is often inefficient, and that even within a uniform object, different areas have unique structural needs that demand tailored solutions.

4. It’s Incredibly Light, Strong, and Made from Recycled Plastic

The final optimized design isn’t just a compelling concept; the data proves its real-world viability. The project’s success, unveiled in its final phase, is quantified by its impressive performance metrics and material choice.

The pavilion is designed to be built from Glass Reinforced Recycled PET, a strong and sustainable composite. The final optimized mass for the entire structure is a combined total of approximately 160 kg—just 73 kg for the outer shell and 87 kg for the inner. Despite this low weight, the pavilion is exceptionally strong. The two-part structural solution paid off: under a simulated load, the outer shell’s maximum deflection (how much it bends) is a mere 1.41 mm, while the more delicate-looking inner shell deflects only 0.06 mm—both well within architectural safety limits. These stats confirm that the process can yield a feasible, high-performance structure that is elegantly efficient in its use of materials.

Conclusion: A Recursive Idea Worth Chewing On

The Cappelletti Pavilion’s journey—from a mathematical formula in a book to a human-scaled form, then through thousands of digital generations to a fully optimized architectural design—showcases a powerful new workflow. It proves that inspiration can come from the most unexpected places and that computational tools can translate that inspiration into something remarkably efficient and buildable.

As a final, whimsical detail, the project’s visualizations depict people relaxing inside the pavilion while eating bowls of Cappelletti pasta. This makes the entire experience “fully recursive”—a structure born from pasta, designed to be a place to enjoy pasta. It’s a fitting end to a project that so elegantly connects the mathematical with the material, and the digital with the delicious.

If a simple pasta shape holds the code for a stable structure, what other everyday objects are hiding the blueprints for the future?