Introduction

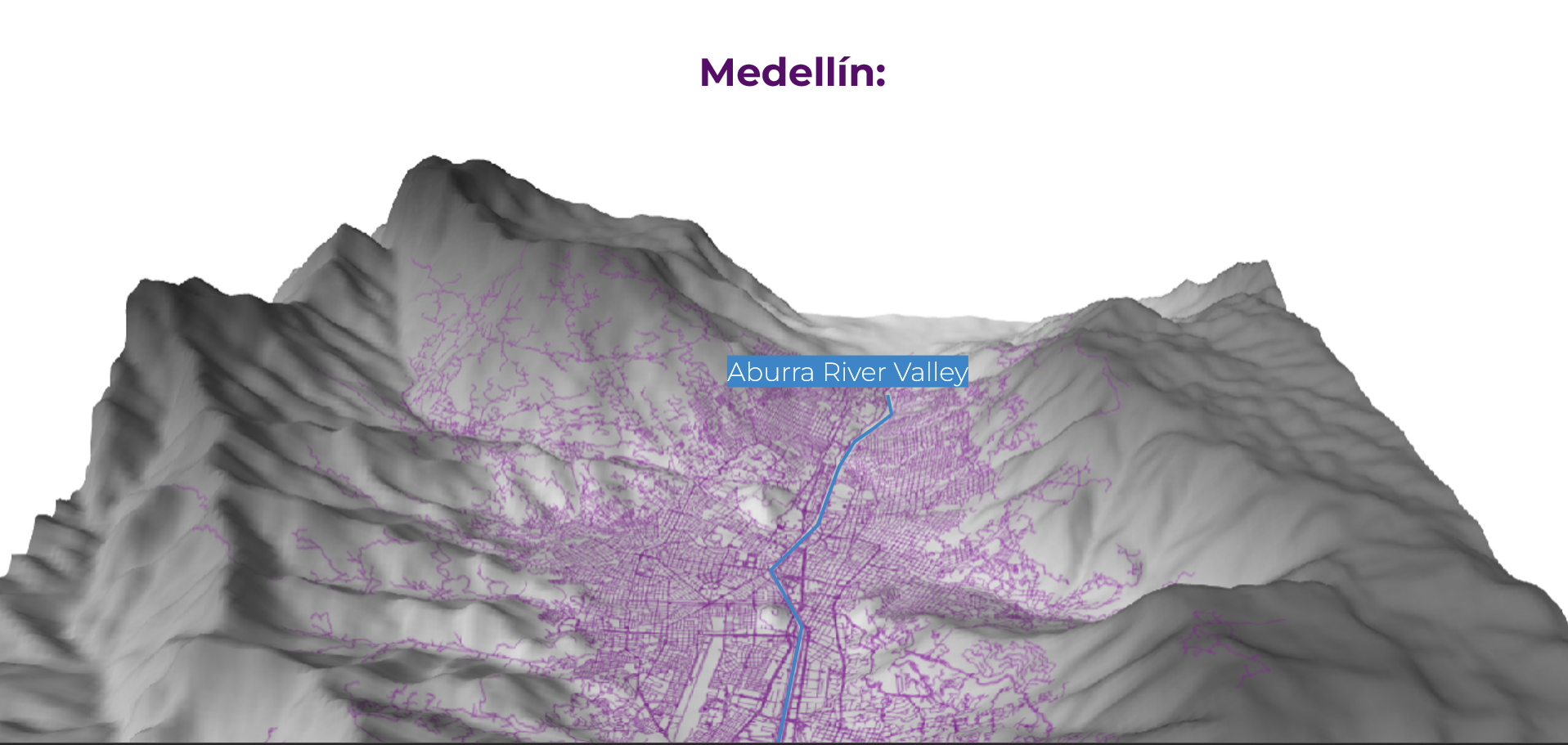

Medellin, known as the ‘City of Eternal Spring,’ is a Colombian city located between mountains around the Aburra River Valley. According to the National Census, it is inhabited predominantly by women, as 53.3% of the population is composed of women, and a large portion of them perform in areas such as education, healthcare and caregiving.

Spatially, Medellin’s built infrastructure is mostly located within the riverbank. The city’s original plan (Plan Piloto) was to build in the surroundings of the Aburra River, which are areas of lower slopes, but, due to the phenomenon of industrialization and the period of La Violencia (Internal Armed conflict in Colombia), large numbers of migrants reached the city looking for opportunities and an escape from violence. As some of these people were displaced and didn’t have the economic resources to move to the existing housing, they started building their own places in the city’s peripheries, which correspond with the areas of higher slopes, and, therefore, natural hazards.

Recognizing this pattern of vulnerability, the project focuses on La Loma, an informal settlement formed in the 1950s and 60s, when farmers parceled out the lands to work on crops that they could sell in the Medellín market, that expanded in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the arrival of hundreds of displaced people from Urabá and other sectors of Antioquia.

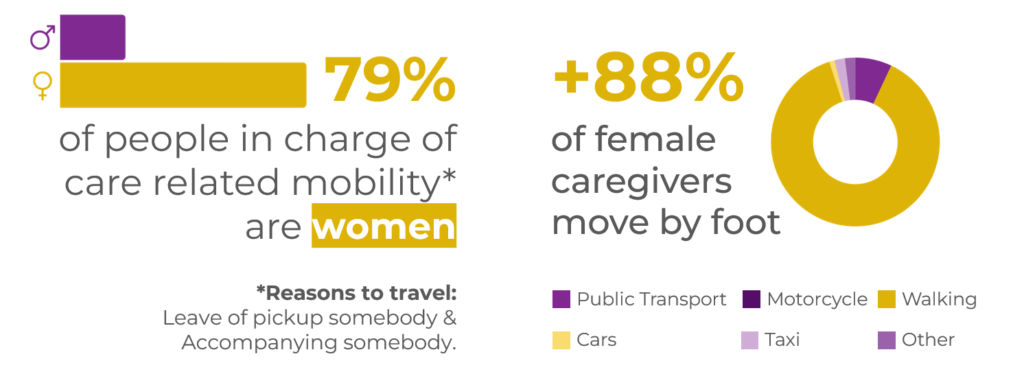

Finally, when looking back into the gender lens through interviews facilitated by an insider, we learned that women in La Loma primarily handle childcare and adhere to traditional patriarchal roles perpetuated by local media. This finding was corroborated by the municipality’s Mobility Survey, indicating that over 79% of care-related mobility participants are women, predominantly traveling locally by foot.

Caregivers and their mobility patterns

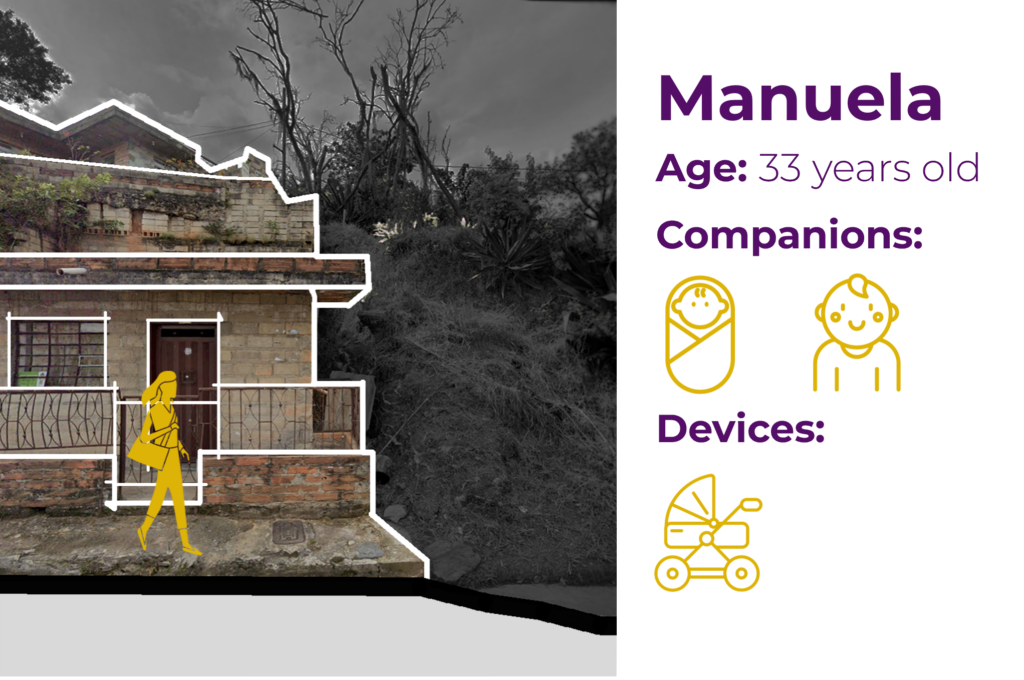

Our research led us to focus on caregivers, recognizing their vulnerability (related to the historical conditions of the neighborhood), essential societal roles, and often unrecognized labor. To illustrate this, let’s take a look into a day in the life of Manuela, a 33-year-old caregiver in La Loma:

Manuela, like many in her community, looks after her neighbors’ children, navigating steep slopes, dead ends, discontinuous sidewalks, and a lack of public resting spaces related to the topography and self-built conditions of the neighborhood.By

If Manuela was not a caregiver, she would simply travel from home to work in the morning and then come back home in the afternoon, through what is considered a pendular movement.

However, as Manuela is not traveling by herself, she has to make additional stops, leave kids at school, home errands, arrangements and stops that are usually outside of her linear path to work. This is considered a polygonal movement, and it implies that Manuela goes at a slower pace, and takes longer to reach places.

Estimations based on the local Census and network analyses suggest that San Javier has at least 600 women like Manuela, with about 150 taking children to Loma Hermosa School.

The combination of these insights led to multiple questions: How can we support caregivers like Manuela in making informed decisions by leveraging already existing tools within the community? How can we highlight and address the barriers they face daily?

Methodology

How can we take advantage of community’s existing tools to make mobility barriers visible, support informed decision making and inform participatory spatial transformation?

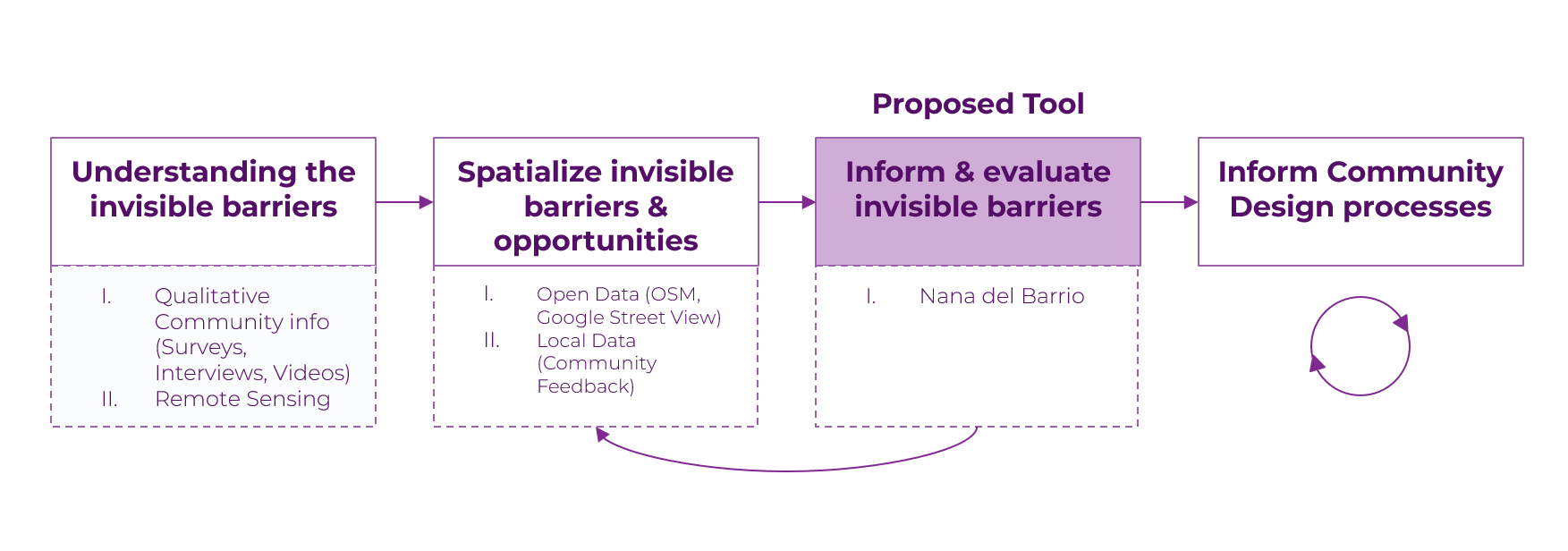

To find answers, we map a methodology that involves multiple steps:

- In primary attempts to understand the invisible barriers that most caregivers encounter, we do qualitative research through surveys and delve deeper into open-source data using OSM and Google Maps.

- Further on, we spatialize this information into discernible maps and interpret its reach.

- Conclusively, we propose a tool that allows caregivers to have access to qualitative information and provide feedback on the existing conditions.

- This same tool can be the initiative for engaging with and informing co-design processes.

Invisible Barriers

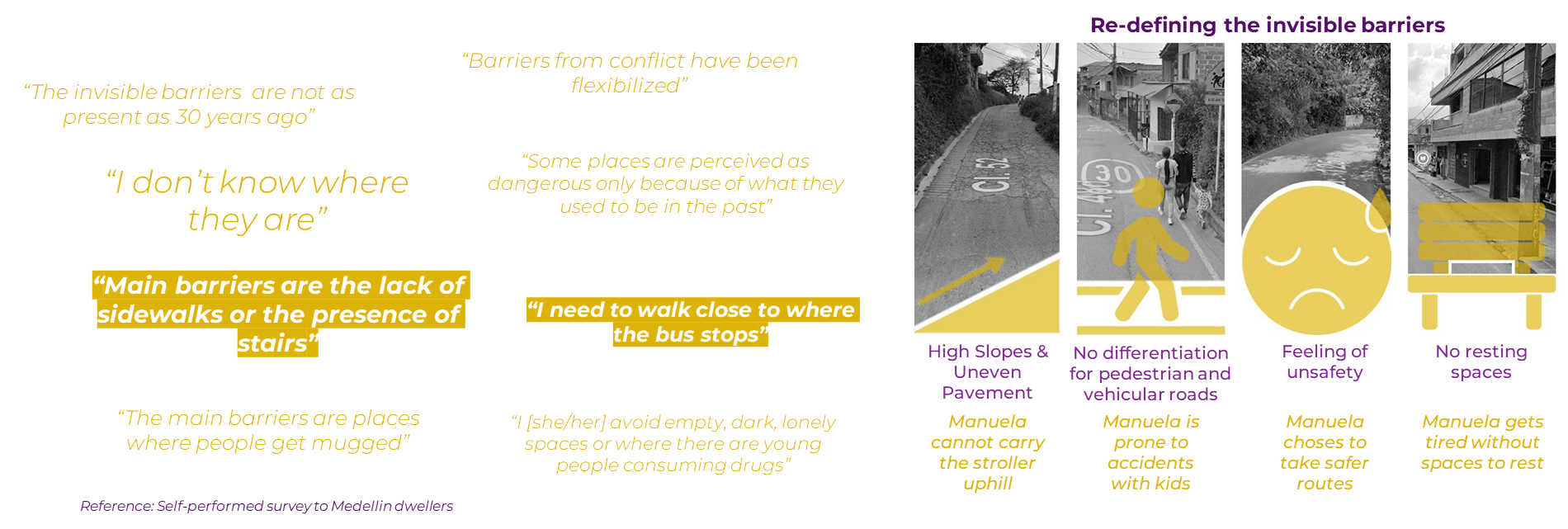

The term “invisible barriers” is a common concept in the context of Medellin. Historically, it was linked to the presence of violence and refers to spaces that cannot be crossed due to rules imposed by illegal armed groups within the city. As San Javier is a historically vulnerable neighborhood, we commenced to see the significant impact of these barriers on mobility patterns of the said caregivers.

However, in our initial engagement with the community, we discovered that most residents do not have a clear understanding of where these barriers are located. Likewise, they mention these barriers are not as significant as they were previously. Instead, they identified spatial characteristics such as steep stairs or eyeless streets as barriers. Taking into account concurrent comments from the community and our observations we strive to re-define invisible barriers. Therefore, we have redefined the invisible barriers in terms of 4 categories:

1. High slopes and uneven pavement

2. Lack of differentiation between pedestrian and vehicular roads

3. Feeling of unsafety

4. Lack of resting spaces

“Invisible barriers”, a concept that delineates the spaces where freedom of movement is altered”

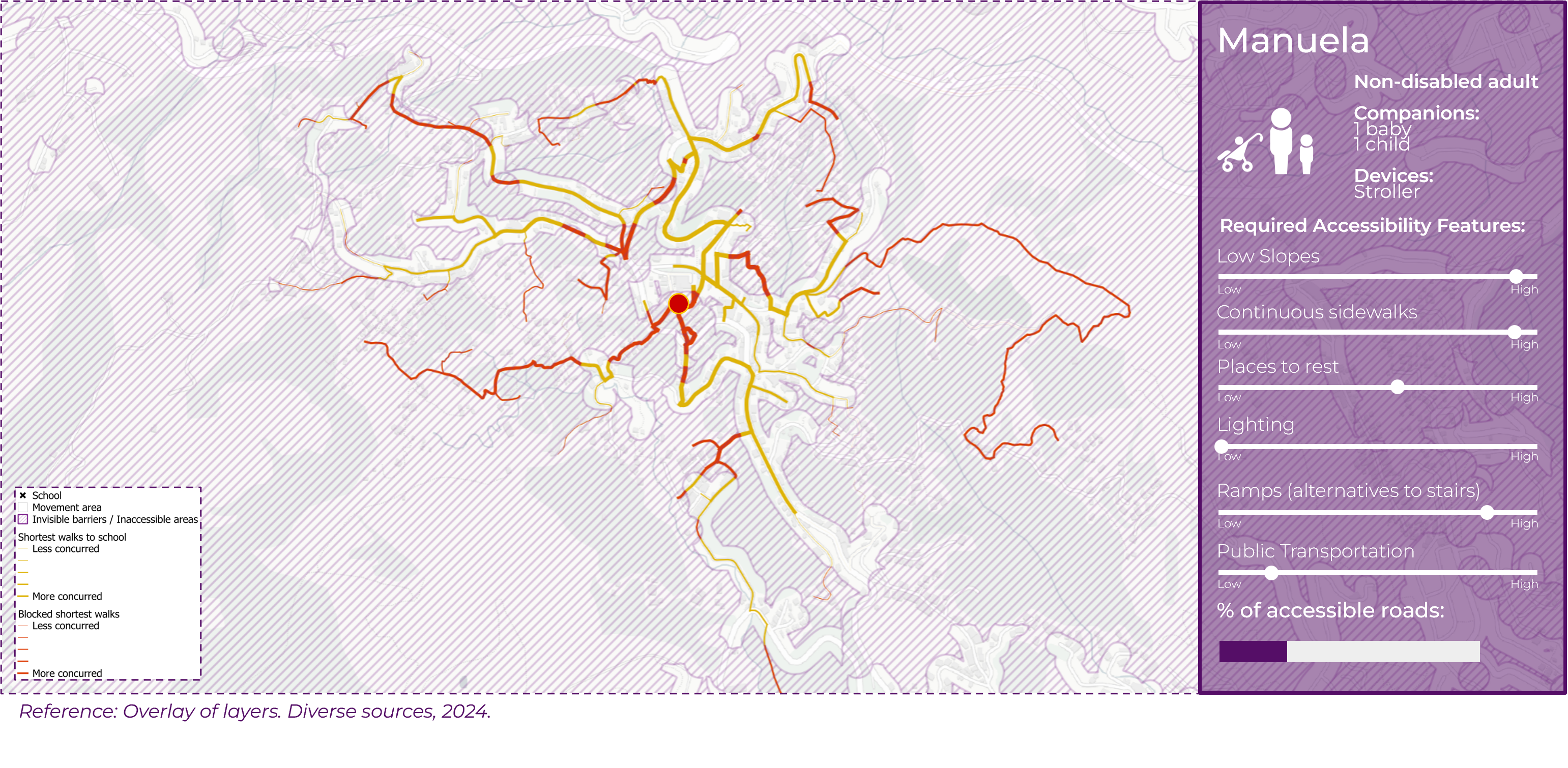

By spatializing and overlapping these layers, it is possible to understand how they reduce the availability of space. It is also important to highlight that they are relative to each person’s condition according to variables such as age, gender, who they travel with or the devices they carry. For Manuela, who’s traveling with children and a stroller, high slopes, the absence of sidewalks and stairs, can limit or halt her freedom of movement. When mapping these barriers, we can see the available routes that Manuela can comfortably traverse are reduced to 26% compared to the available space of a non-caregiver.

To better understand Manuela’s commute, we focused on the most concurrent path based on our shortest path estimations. From above, it looks like a straightforward path that takes about 10 minutes according to Google Maps. But for her, whenever there are high slopes, stairs, or when she picks up a kid and uses a stroller, she gradually gets slowed down, turning an ideal 10-minutes journey into a 17-minutes walk.

Other than slope, on her way she encounters other barriers from the stated categories, such as the lack of sidewalks, sections entirely dedicated for car flow, and stairs.

Invisible Opportunities

Besides visualizing the barriers, we also visualized the opportunities. For that, we queried open data, like OpenStreet Maps, for the available public spaces. The result showed a scarcity of public spaces in the neighborhood.

But when looking at human scale, using Google Street View and videos performed by local contacts, we identified informal uses of public spaces. This highlights not only the unavailability of public space, but the unavailability of top down data informing about it.

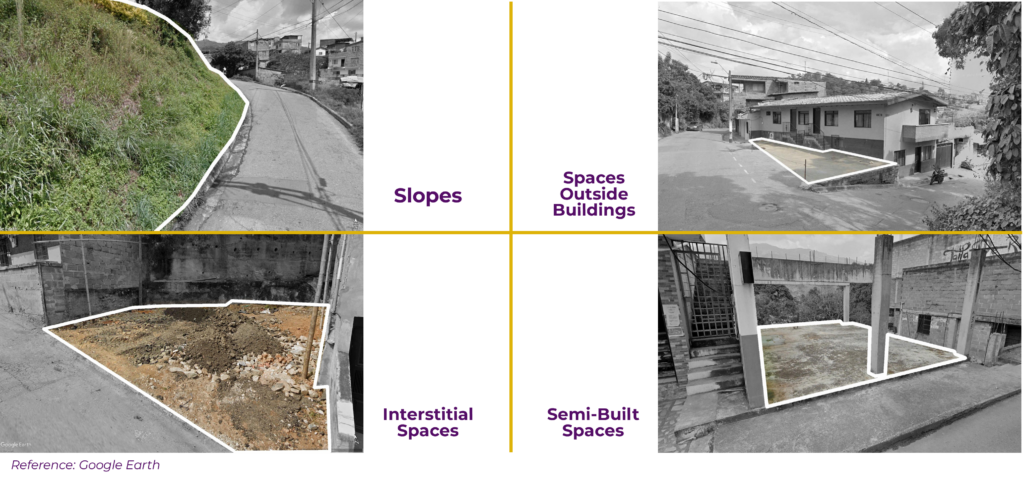

Through this same methodology of looking at the space from the human eye, we identified other types of available space that could be eventually reimagined, like green slopes that are unused, spaces outside buildings that are empty, interstitial spaces now filled with ruins or wastes, or semi-built spaces were not finalized.

Nana del Barrio: a tool for informing and evaluating invisible barriers

To develop the information we have already shared, we intend to learn from the self-made community as it holds more knowledge about the topic.

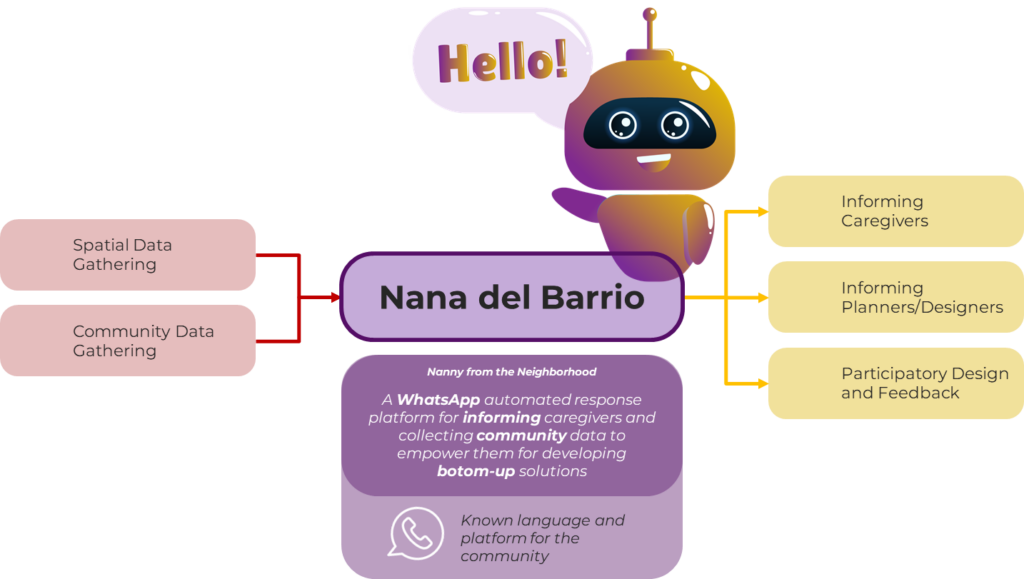

We propose Nana del Barrio, a WhatsApp chatbot for the La Loma community, that serves as an automated response platform for informing caregivers and collecting community data to empower them to develop bottom-up solutions. about spaces in proximity and varied routes, aids planners with suggested possible solutions and spaces of opportunity from the citizen and empowers the community by gathering feedback in WhatsApp chat space.

WhatsApp bot is a platform that is used by a majority of Colombia to communicate their ideas but also as an assistance with multiple requirements of people. In fact, there are multiple more examples of whatsapp chatbots developed by banks, health care providers, stores and more which are the inspiration behind Nana del Barrio.

Let’s take a look at how Manuela can use our platform on a daily basis. During her first interaction with the chatbot, Nana will ask Manuela about basic details like how she travels, who she travels with, and if she uses any special devices. This information will be used to create her profile, choose the best routing options and will be stored for future inquiries. Then she will be given three options: being taken somewhere, finding places and reporting something.

In this case, Manuela wants to know about resting spaces. And the required input for the chatbot is either a location from WhatsApp or an address. The information that Nana provides are the locations that have been stored in our database as places to sit, and they are shared as pins on google maps. The added value of our platform from using Google maps is having inputs from the community and our previous research and not just open data. However, Nana’s reach doesn’t end here. Manuela can also use the chat to get a route that accommodates her needs. In this case she gets it by simply choosing the place where she wants to walk.

Nana provides a Google Maps route that takes into account the possible barriers according to Manuela’s profile. In this case, it’s a route safe for strollers and children.

Now imagine Manuela encounters a previously unknown barrier that disrupts her journey. In this scenario she can simply use the option report within the chat to add it to the database by sending its location. This means that the community can input the information that is being used for recalculating the routes and the amenities in the area.

Apart from individual conversations, WhatsApp groups are a very common form of communication within the community.

Neighborhoods and schools usually have specific groups for informing multiple people at once and coordinating activities. Therefore, including Nana as a member of these pre-existing digital communities, is an opportunity to interact with them and gather community insights.

When added into a group chat, Nana can register permanent or temporal incidents shared between the members of the group, such as Juan who wants to report a street closure, and ask for the necessary details to geolocate them. and store them in a compiled database.

These events and reports can reference both negative and positive aspects such as this case, where Ana is providing spaces for people to rest during certain hours of the day. This engages mutual information between the community and fosters the use of communal spaces, all this, while Nana can gather bottom-up information to enrich data compilation.

Nana del Barrio as a co-design tool

So far the bot has been used mainly for helping caregivers identify barriers and providing them directions to avoid them. But the chatbot also is a tool for a final step, where the municipality designs and deploys interventions that make the space better for caregivers. To ensure that the future projects are well suited to the people, we envisioned a four step framework that leverages the use of the chatbot for co-designing spaces.

- Identify needs and spaces of opportunity based on the interaction of Nana with the community

- Socialization of design ideas through WhatsApp groups to get feedback from the community

- A final proposal is deployed as a tactical intervention

- Evaluation period: if the space is successful it can be transformed into a permanent intervention

At every transition between steps if an idea or design is deemed unfit the designs can step back to the previous stage and continue from there. This framework is meant to work as a continuous process where multiple interventions are being developed and deployed continuously, based on the needs of the caregivers gathered from the chatbot.

By proposing Nana del Barrio, we aim to continuously gather data and inform the community using a familiar platform. This approach not only addresses immediate caregiver needs but also fosters long-term, community-driven urban development.

However, we recognize that Nana del Barrio is just a first step. There is still a need to redistribute caregiving tasks more equitably across genders and to acknowledge caregiving as valuable labor. Efforts must be made to challenge and change the societal norms that confine these responsibilities predominantly to women. Only by addressing these broader issues can we hope to achieve true gender equality in caregiving. Nana del Barrio lays the groundwork for this change by empowering caregivers and highlighting their critical roles, but it is part of a larger, ongoing effort to create a more equitable society.

Juan Camilo, Azucena, Nupur & Pedro

References

- Sánchez, P. (2018) Ciudad planeada, ciudad habitada. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas (Universidad de Antioquia).

- Pérez Rivera, P., et al (2021) Masculinidad y paternidad en procesos de crianza en Medellín, Colombia. Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública (Universidad de Antioquia). DOI: https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.rfnsp.e344529

- El Descontrol, et al. (2023). Arte, memoria y vida: Comuna 13 y La Loma. Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica

- Pérez Fonseca, A. (2017). Las periferias en disputa: Procesos de poblamiento urbano popular en Medellín. Estudios Políticos (Universidad de Antioquia), 53, pp. 148-170 DOI: http://doi.org/10.17533/udea.espo.n53a07

- Área Metropolitana del Valle de Aburrá. (2019). Encuesta origen destino. Metropol.gov.co

- DANE (2018) Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2018

- Cañola, J.K., Osorio, J.M., Cardona, L.A., & Rodríguez, E.M. (2013). Fronteras invisibles: como espacios formativos para la construcción de interacciones sociales. Universidad San Buenaventura.