URBAN WAYFINDING FOR THE BLIND

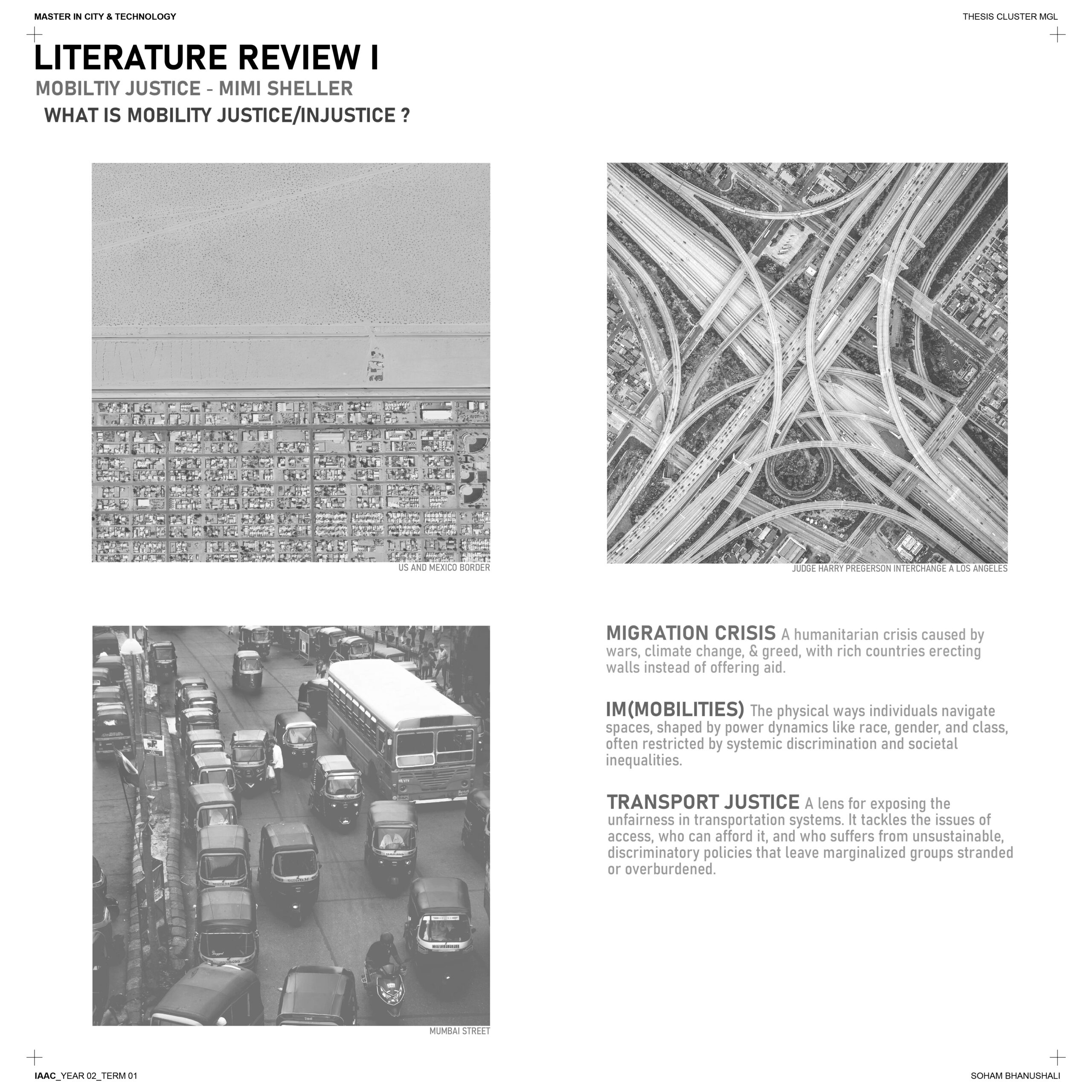

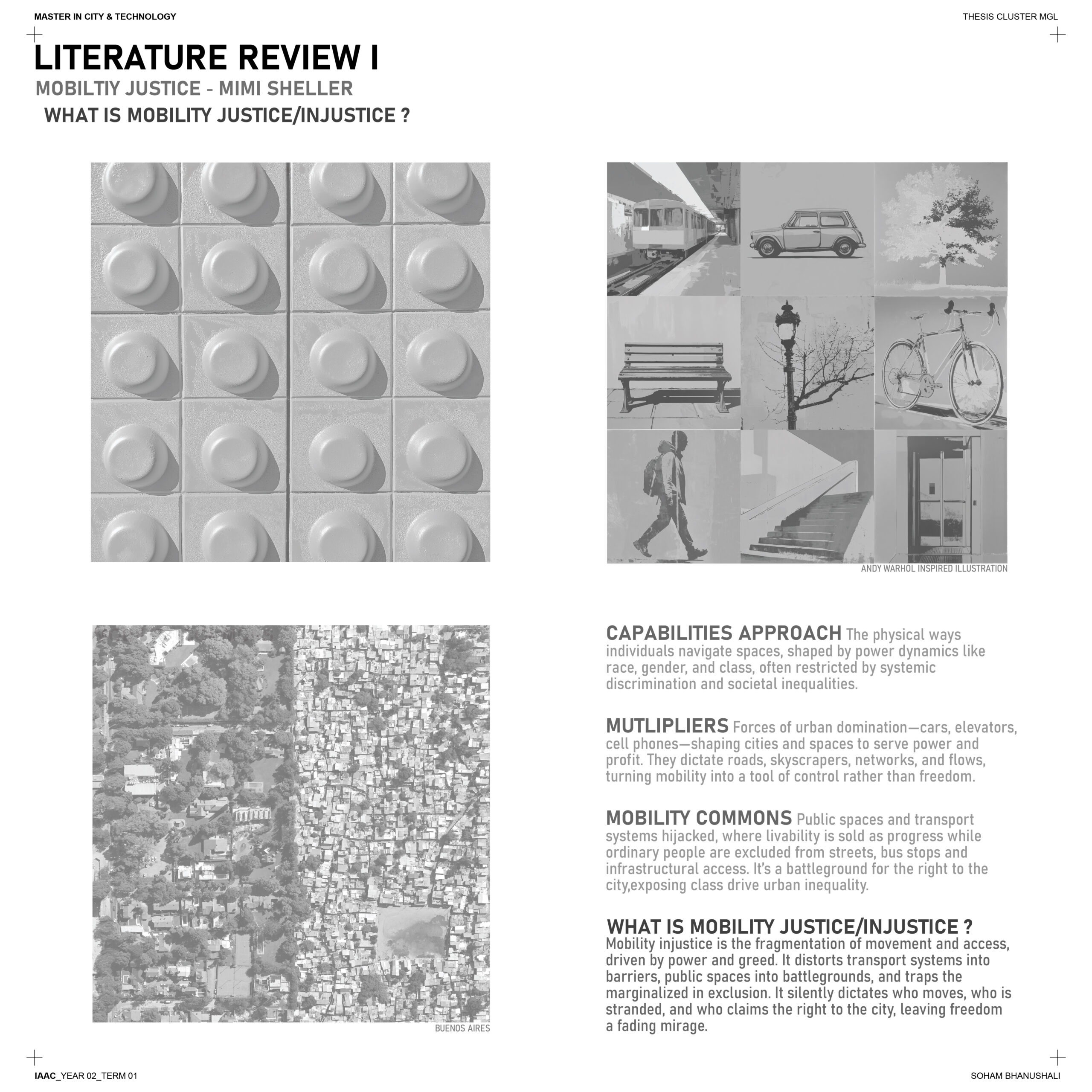

Understanding how visually impaired or blind individuals navigate urban environments reveals significant challenges tied to mobility injustice across various scales. This issue extends beyond individual obstacles, encompassing systemic gaps in urban design that fail to accommodate diverse needs.

My thesis delves into these injustices, exploring the barriers that hinder equitable access to city spaces. More importantly, it aims to propose a more streamlined approach to wayfinding—one that seamlessly integrates varying spaces and pathways within the urban fabric. By addressing these issues, we move closer to creating cities that are truly inclusive and navigable for all.

The process I’ve undertaken follows a funneling approach, starting with a broad exploration of mobility injustice and progressively narrowing the focus. This journey begins with addressing systemic barriers and then shifts to examining individualistic injustices tied to bodily capabilities.

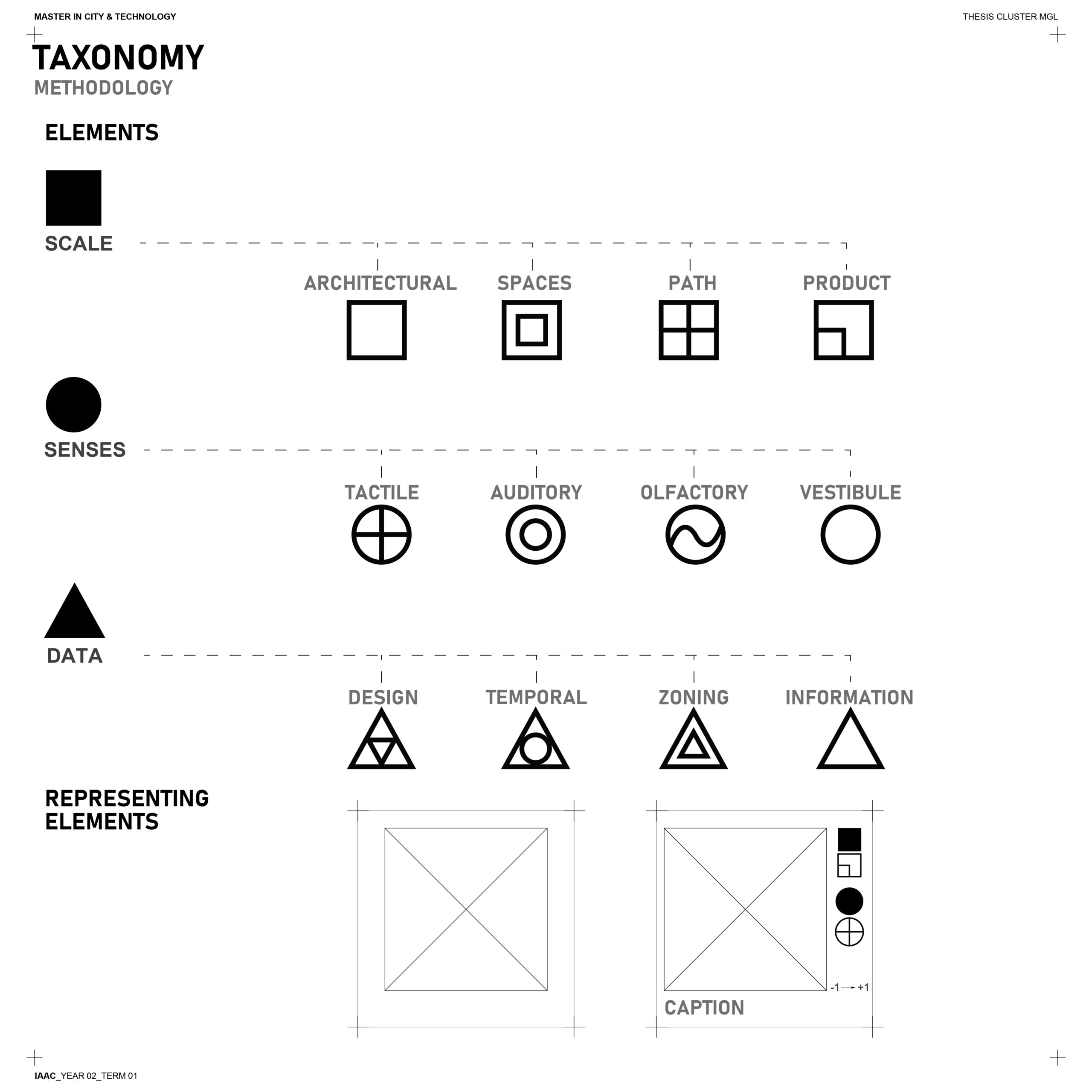

To ground this analysis, I conducted an experiment designed to establish a foundational taxonomy of wayfinding challenges faced by the visually impaired. This taxonomy will be subjected to both qualitative and quantitative analysis, offering critical insights into the interplay between individual experiences and the larger urban context.

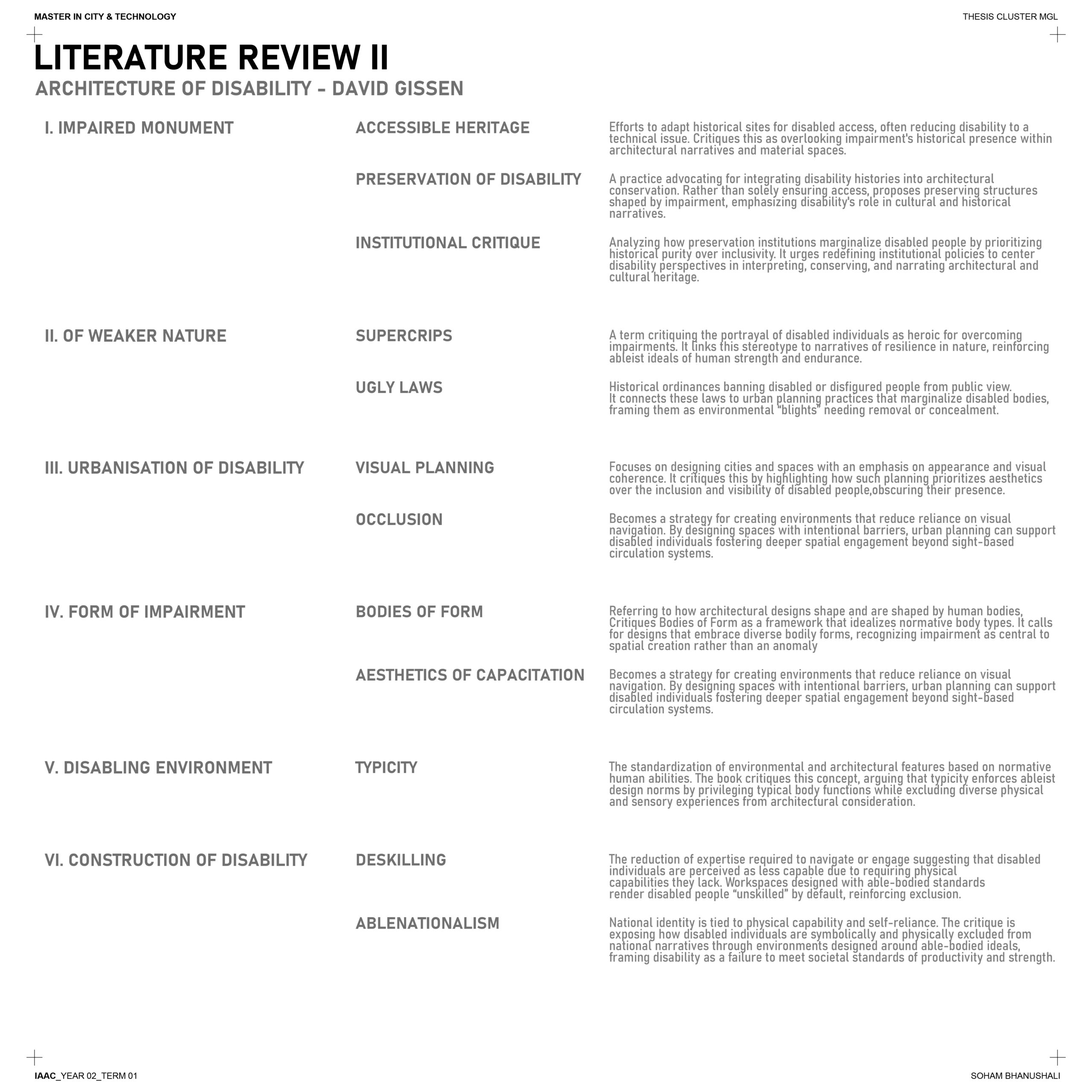

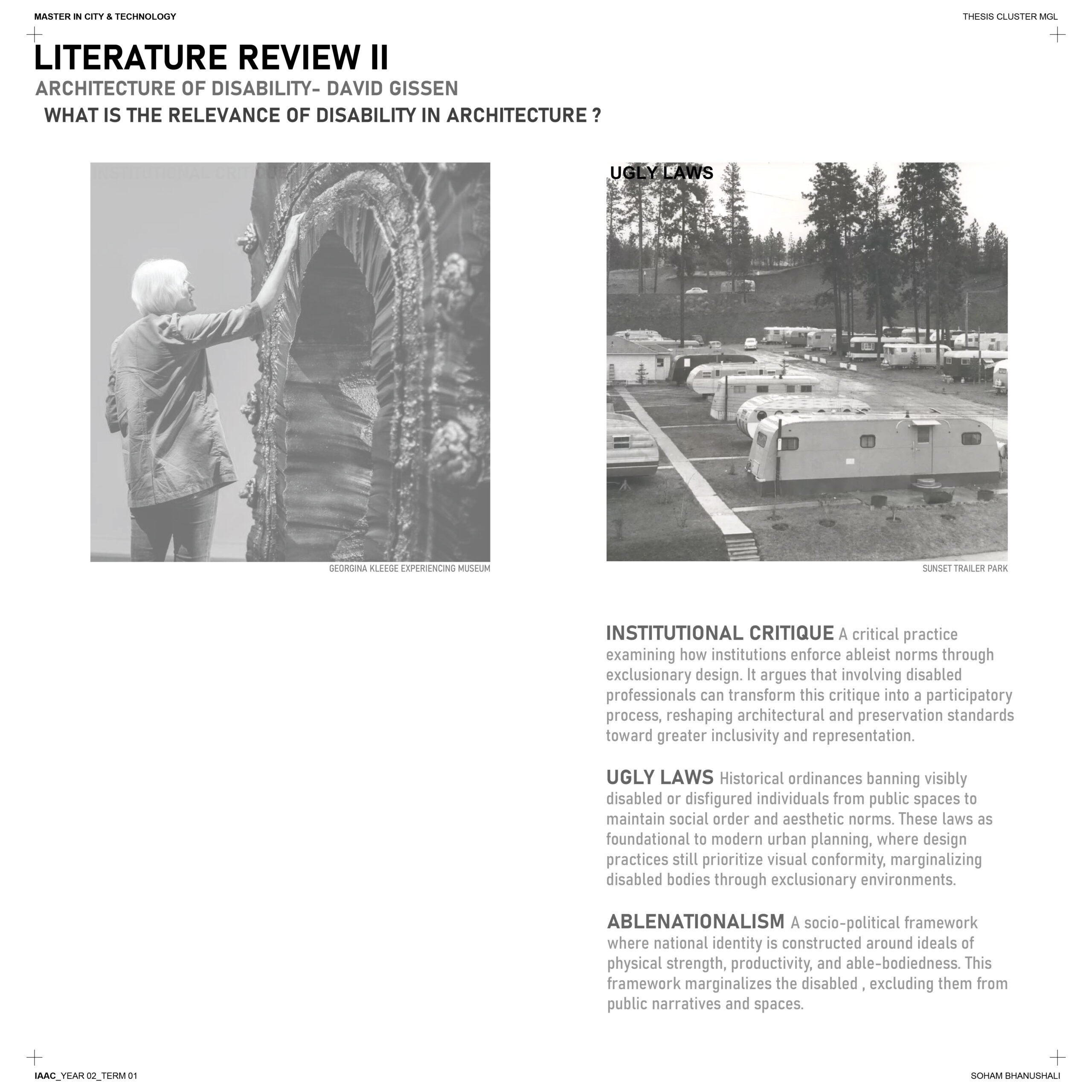

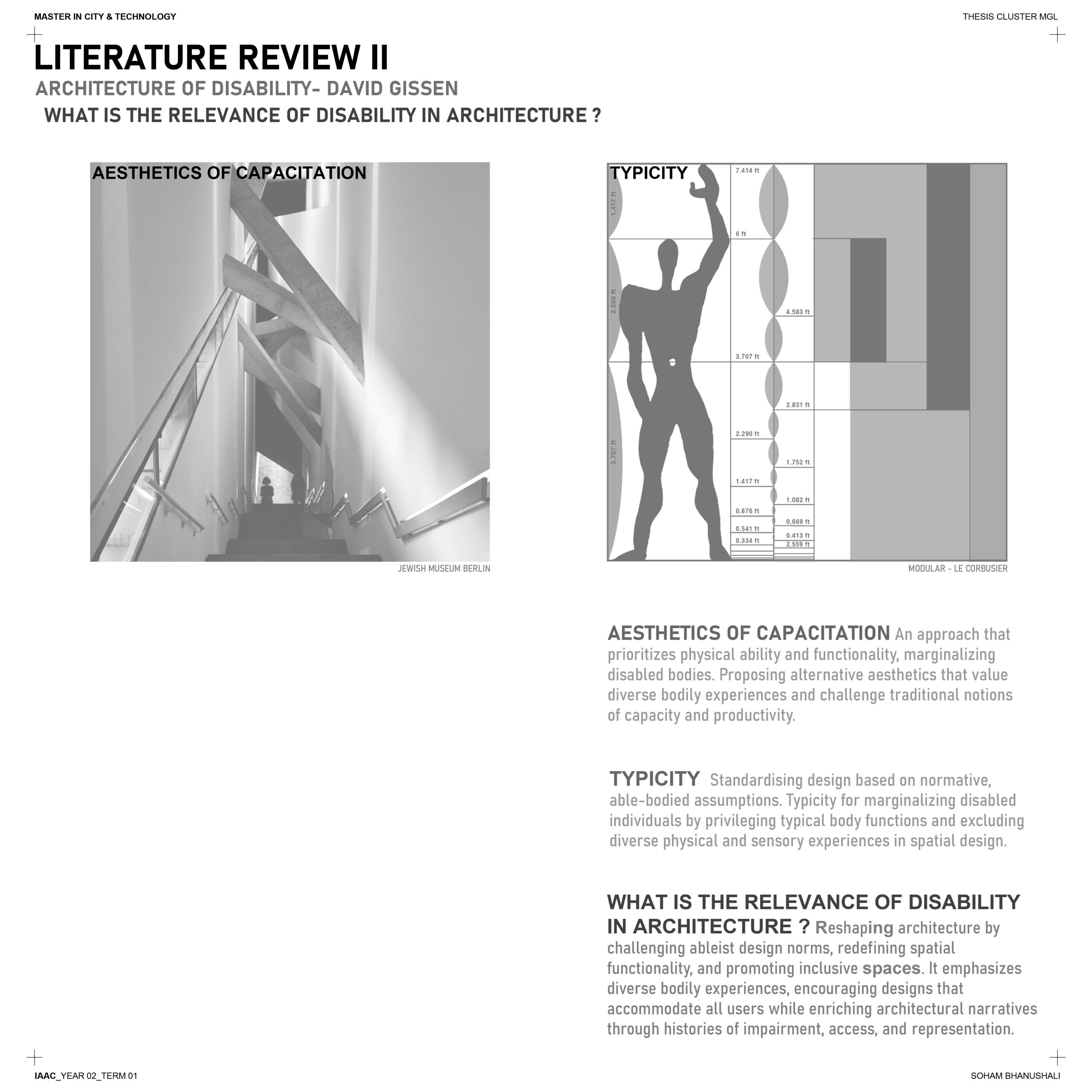

The process of distilling the book involved breaking down each chapter into a glossary-like format and further synthesizing it into well-developed definitions. These definitions were shaped by my questions, opinions, critiques, and key citations. This method allowed me to extract the most prominent principles of the book regarding mobility injustice while engaging critically with its content.

Ultimately, this approach not only clarified the book’s core ideas but also helped me frame a major question: what do I want to learn from this text? By dissecting and reflecting on its insights, I was able to bridge the gap between theoretical understanding and the practical application of its principles in my research.

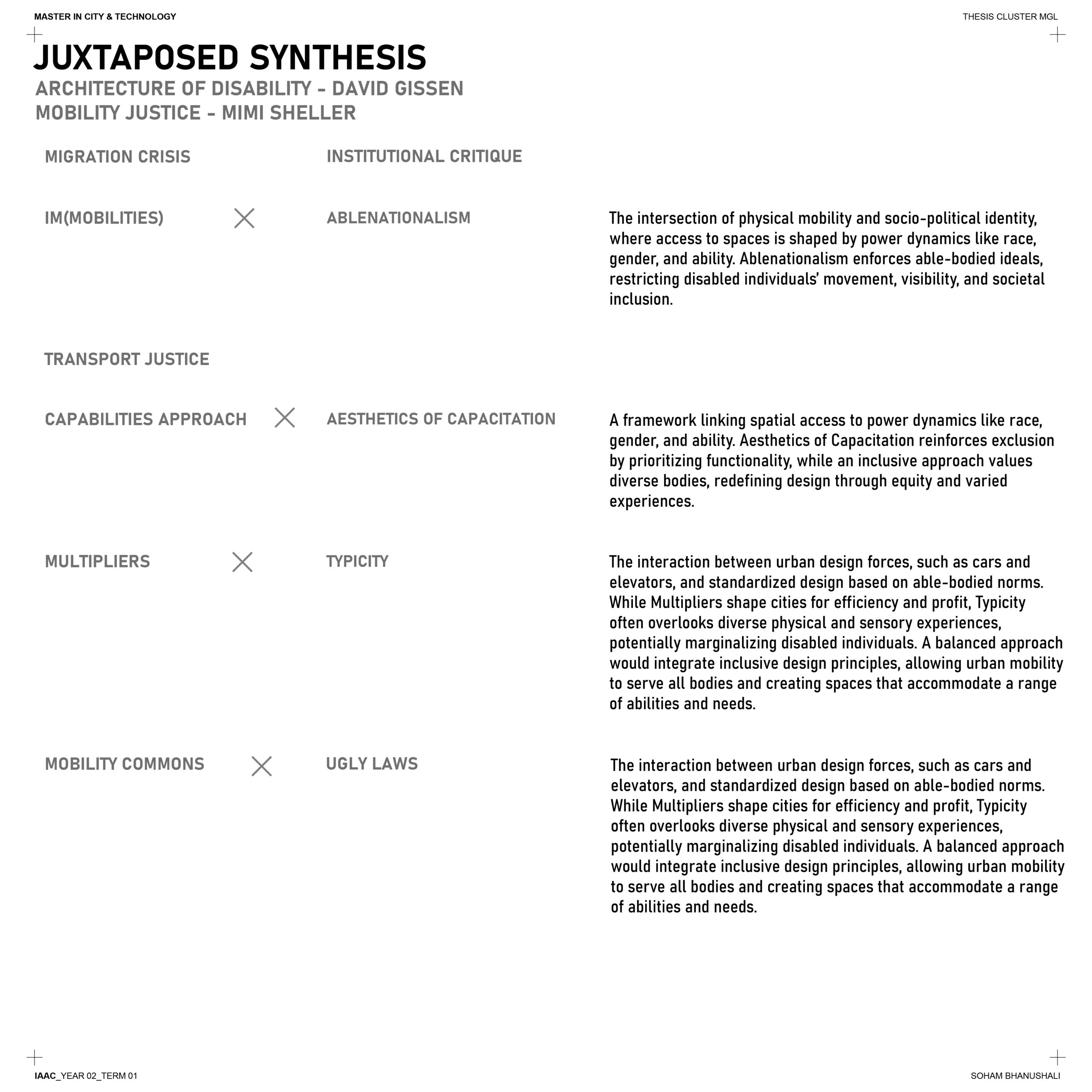

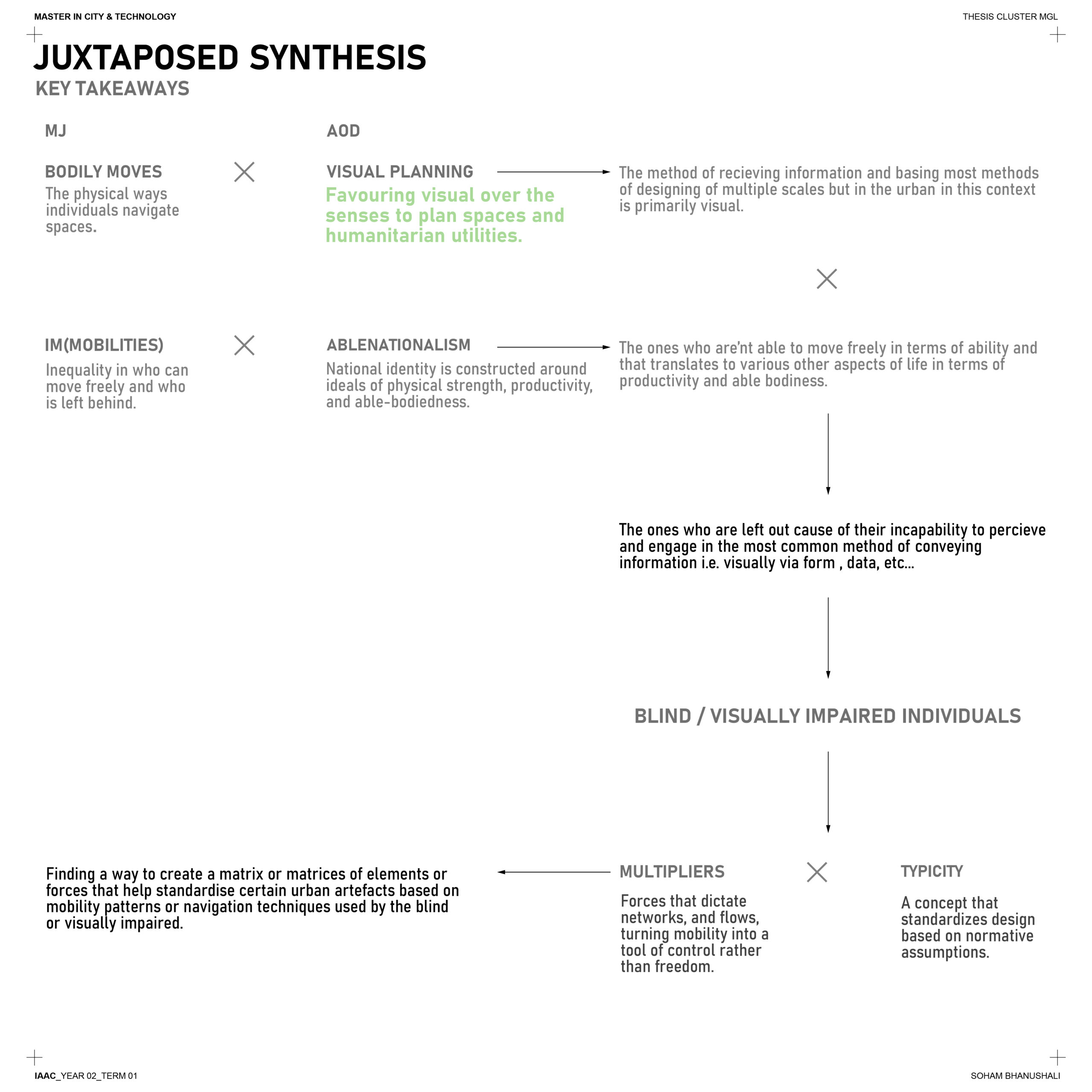

A synthesized understanding of overlapping principles across books, particularly concerning the scales of urban spaces and the individual, has been instrumental in refining the focus of my research. This process helps funnel the broader discourse into a deeper exploration of why addressing injustice toward the blind is not only relevant but necessary.

By integrating these principles, I’ve been able to outline a clear methodology for analyzing and processing this injustice. This approach forms the basis for developing well-informed strategies and designs that aim to create equitable and inclusive solutions for the visually impaired.

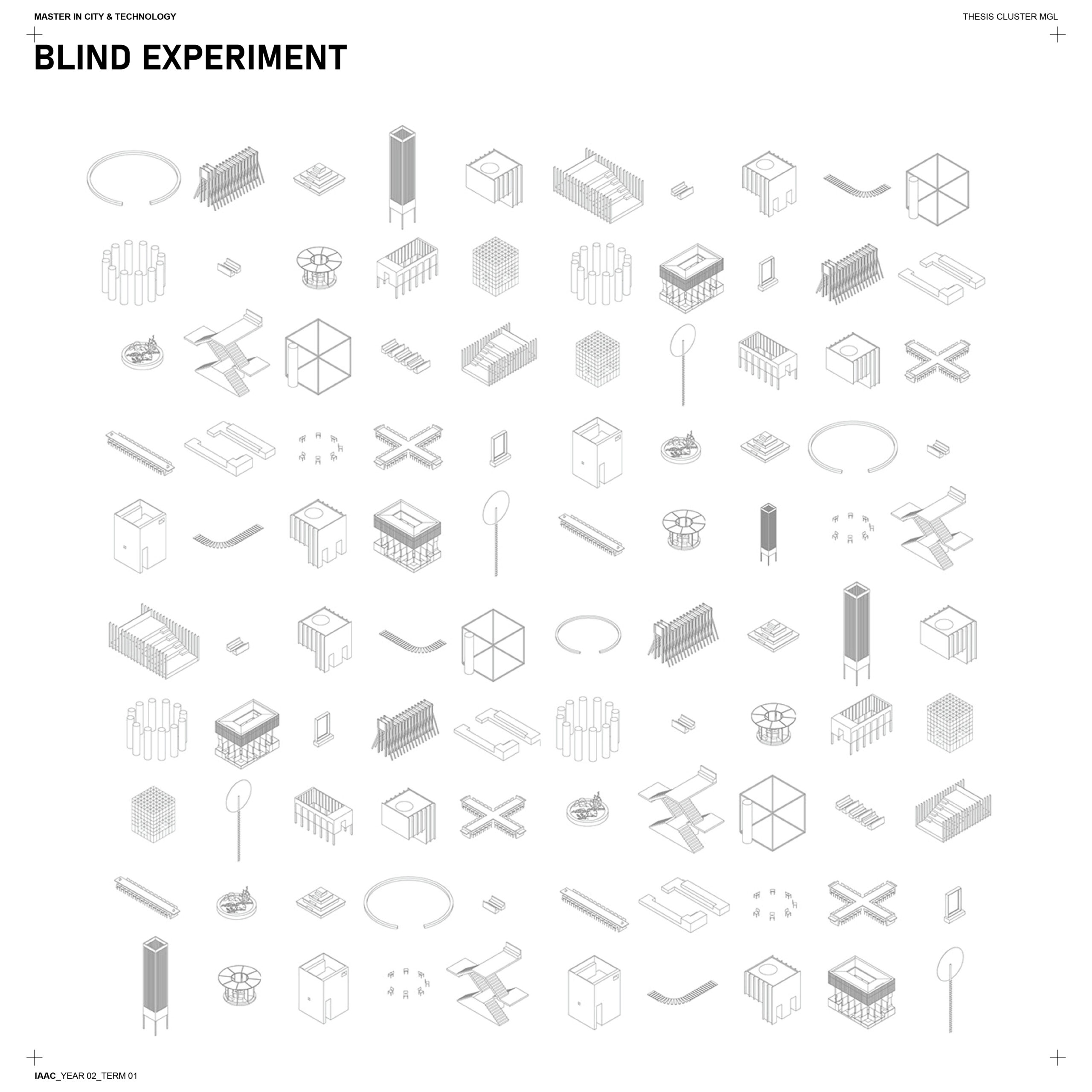

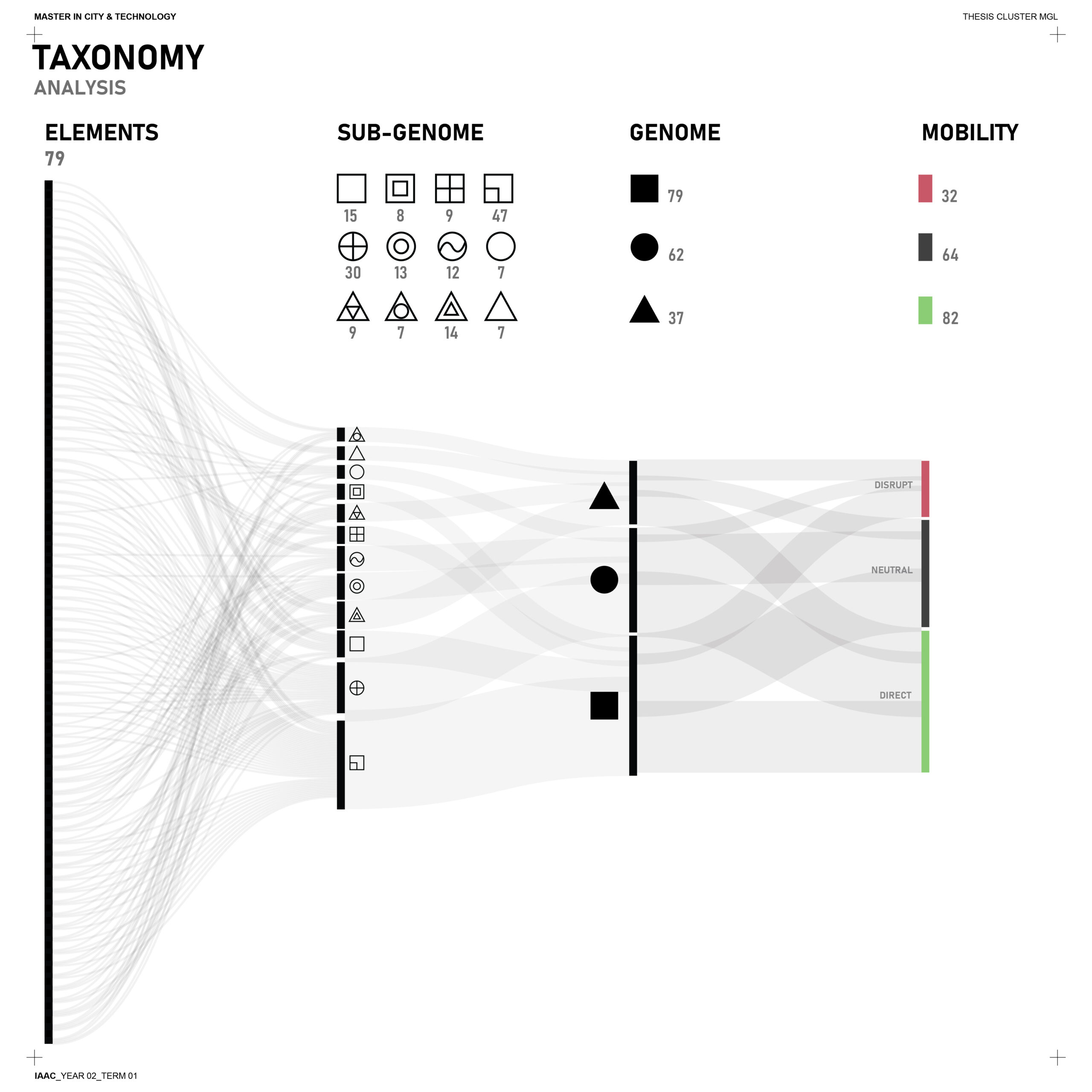

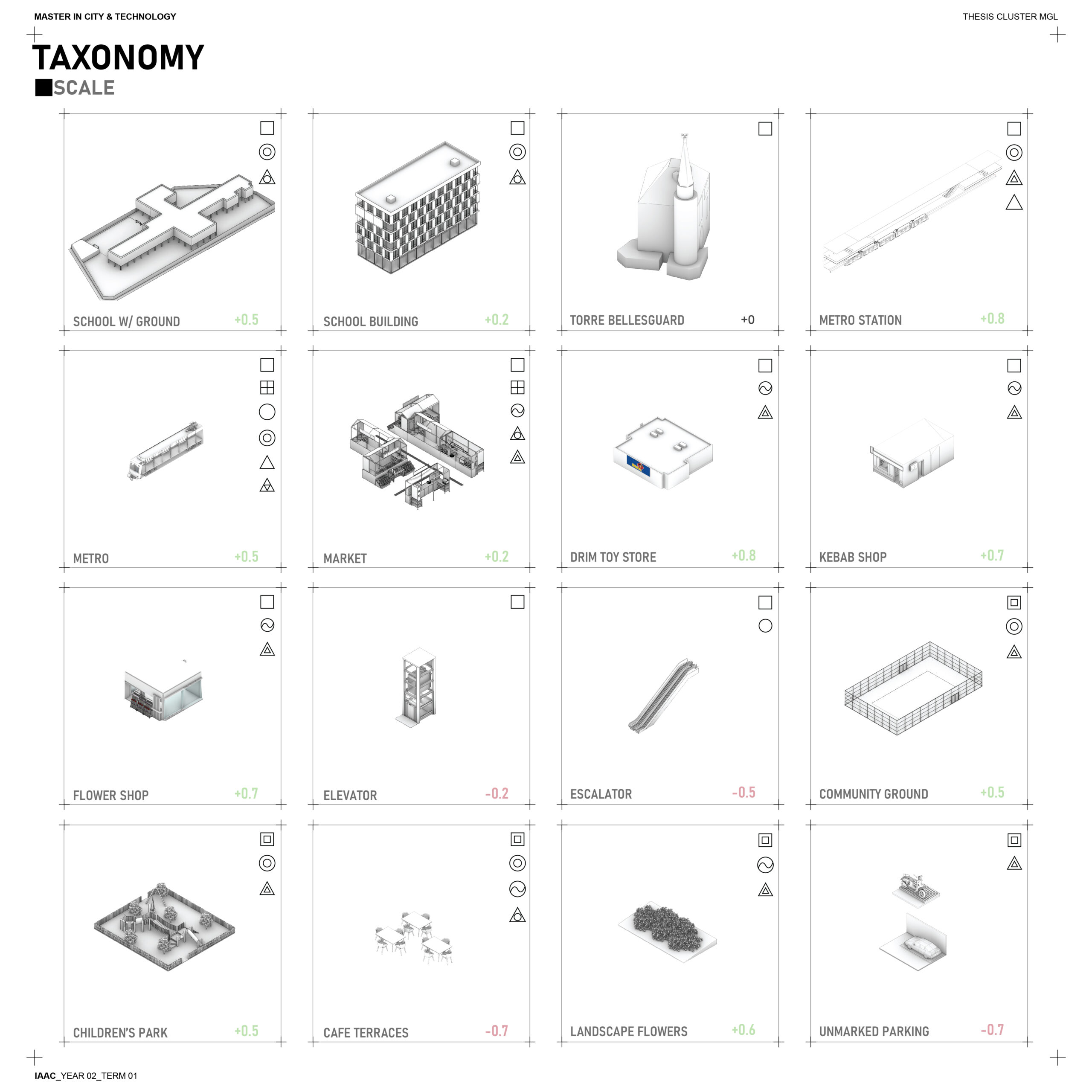

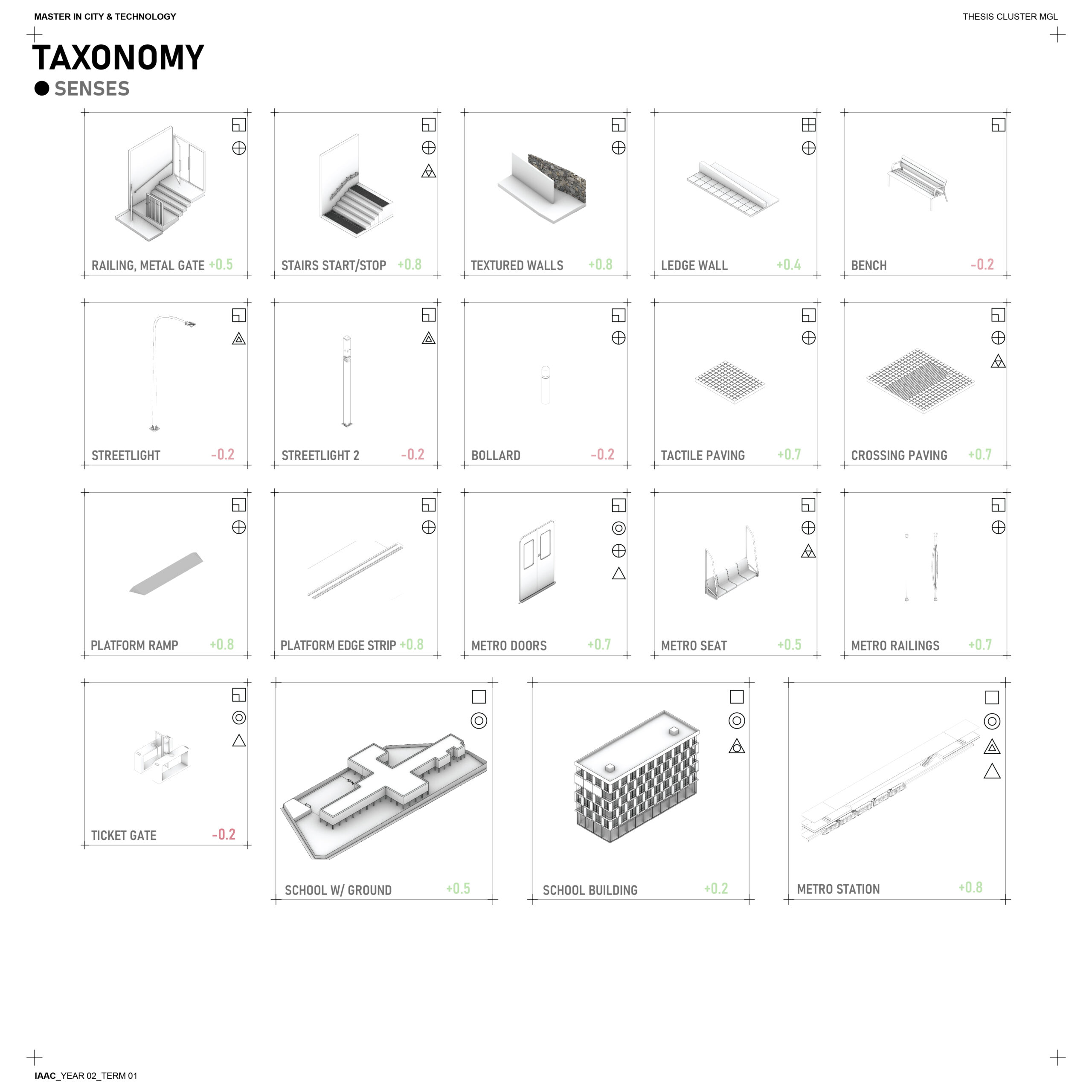

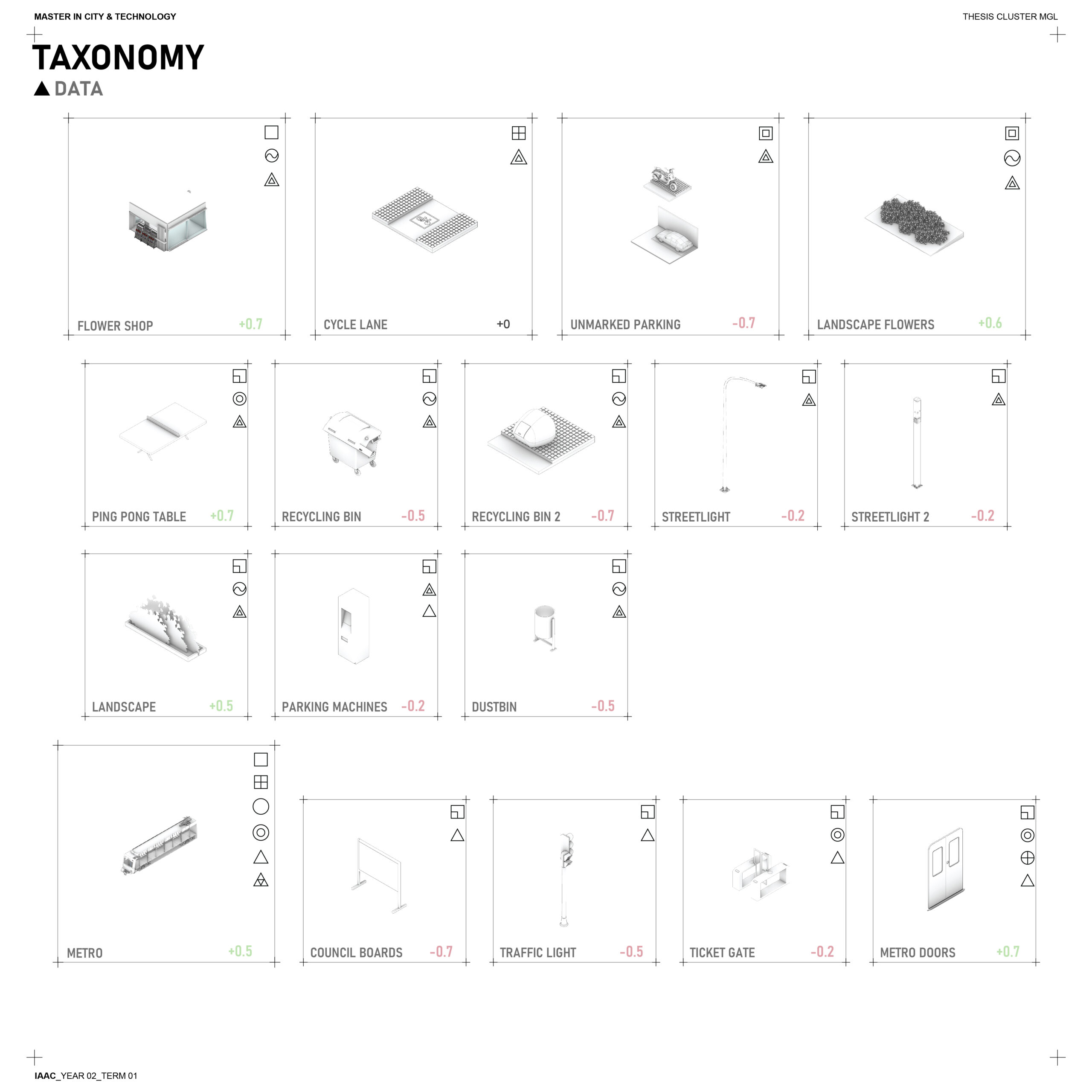

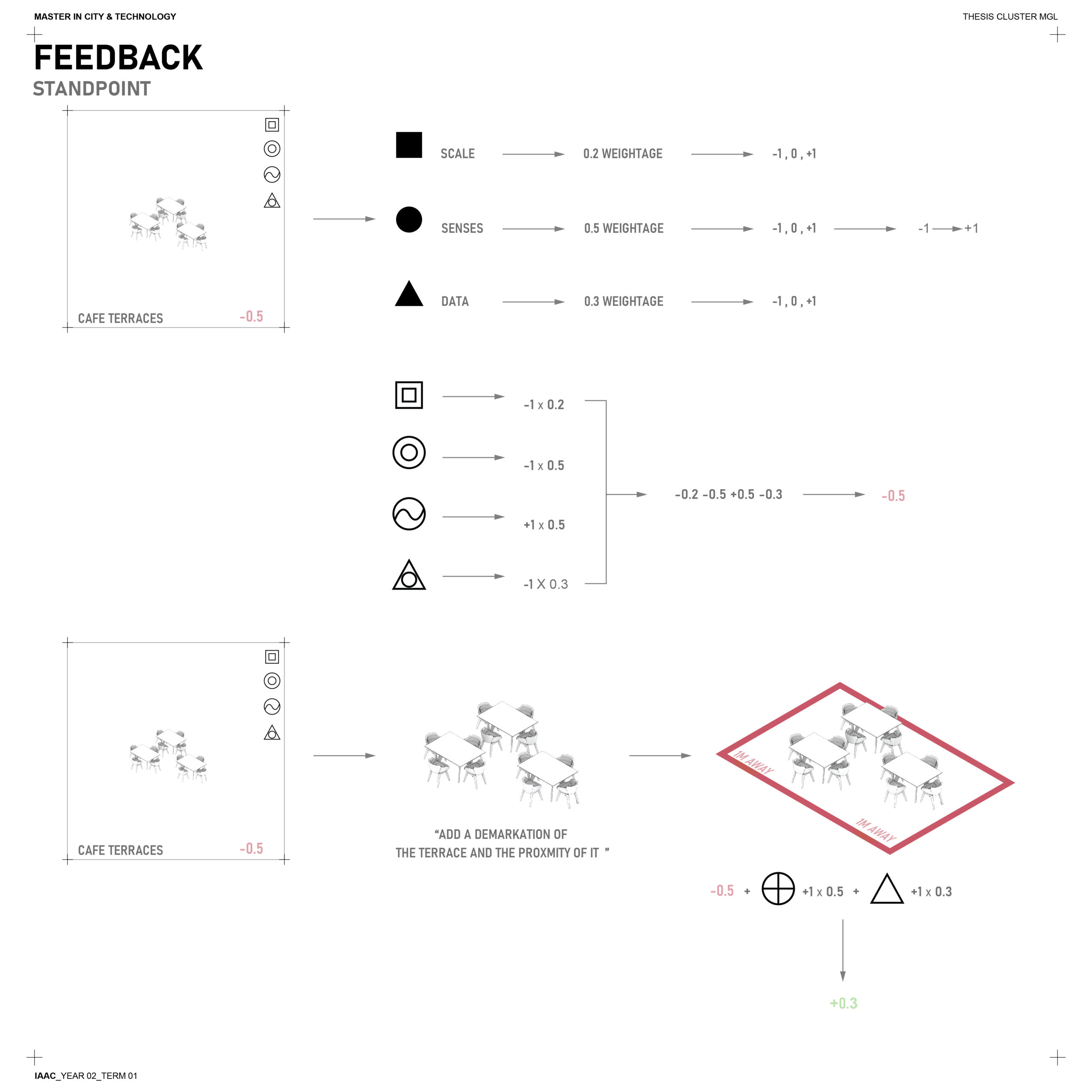

This synthesis led me to break down the understanding of navigation by the blind using the aforementioned multipliers. By employing an inventory method, I was able to create a foundational taxonomy of wayfinding challenges. This taxonomy serves as a framework for further exploration through iterative feedback loops with the individuals concerned.

These feedback loops not only validate the taxonomy but also refine it, ensuring that the insights gathered are deeply rooted in the lived experiences of the visually impaired. This methodical approach bridges theoretical understanding with practical, actionable outcomes, paving the way for more inclusive urban design strategies.

When faced with an overwhelming number of elements to consider, it’s challenging to determine which ones are most relevant to someone who is blind or visually impaired. How do you even begin to map these elements effectively?

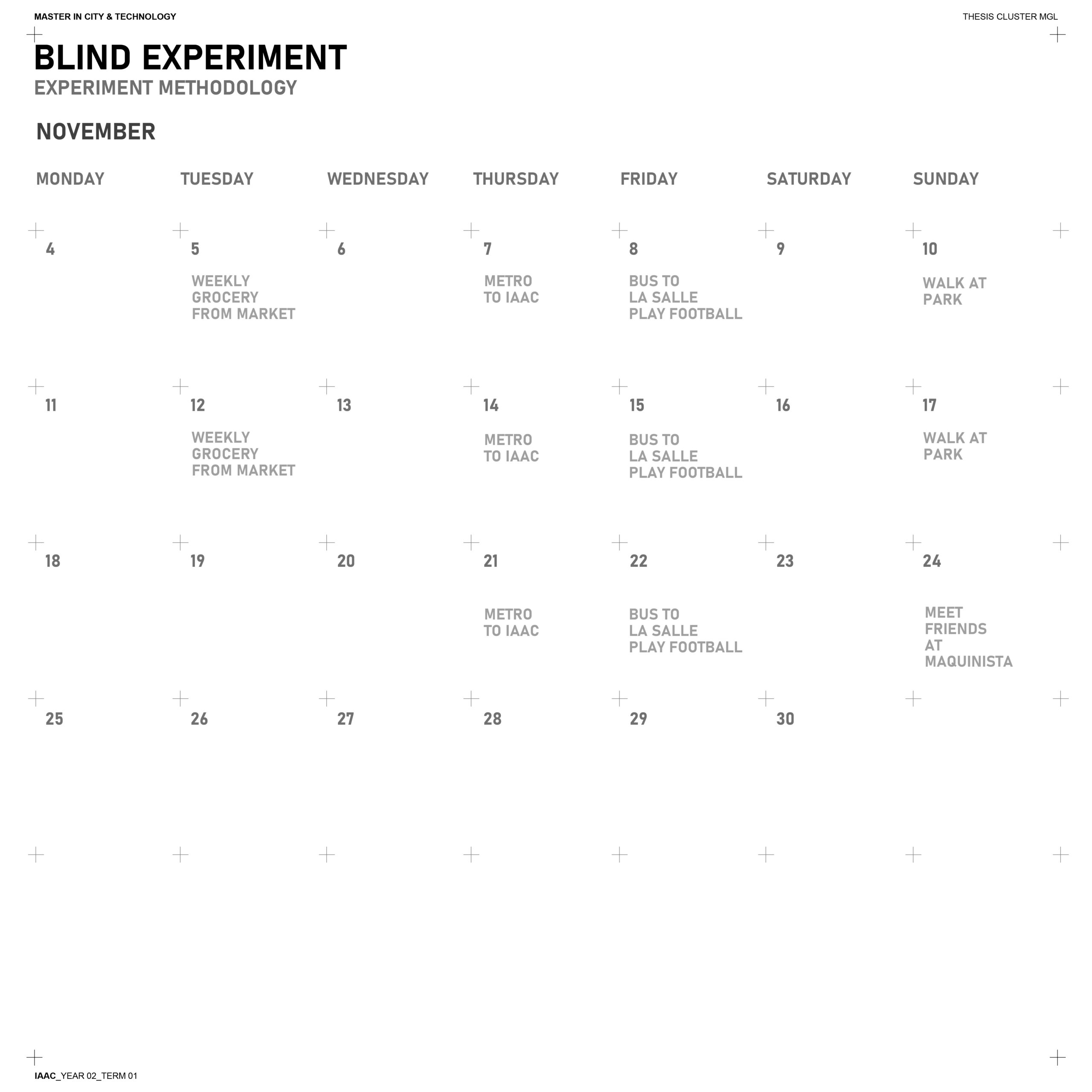

To better understand the challenges faced by the visually impaired, I conducted an experiment where I blindfolded myself and embarked on various journeys. This immersive approach allowed me to experience firsthand the complexities of navigating urban spaces without sight.

Through these journeys, I identified a range of elements or “multipliers”—that influence navigation for the blind. These include tactile surfaces, auditory cues, spatial layouts, and unexpected obstacles. Each element was carefully noted and organized into a taxonomy, serving as a foundation for deeper analysis.

After collecting and categorizing around 89 navigation “multipliers”—with more to come— I developed a scoring system to evaluate their impact. To refine this system, I conducted feedback loops through verbal interviews with blind individuals, gaining invaluable insights into how these elements assist navigation.

This process not only highlighted which elements, or “genomes,” play a more emphasized and weighted role in aiding navigation but also uncovered areas for improvement. Suggestions from participants provided ideas for enhancing these multipliers to make navigation more intuitive and accessible. These refinements are incorporated into the scoring system, ensuring it reflects both the functionality of each element and its potential for improvement.

Even if the physical enablers or systems are in place that may help make navigation convenient for visually impaired or blind people. But would this generally encourage them to break routines or actually access these enabling systems.