El Poblenou is a neighborhood in Barcelona which is experiencing several degrees of transformation leading to urban niches unconsidered. Open City Poblenou envisions public spaces that respond to urban flux, creating environments that encourage interaction and a sense of belonging through co-designed, adaptive interventions by leveraging data-driven strategies and participatory design.

INDEX

00_Introduction

Explanation of Poblenou’s context, its history, today’s situation and the problem statement

01_Data Collection & Analysis

Extracting data from various sources to understand urban patterns, identify vacant spaces, and inform design interventions for Poblenou.

Analyzing data to uncover insights, pinpoint underused spaces, and inform design strategies that address urban challenges in Poblenou.

02_Participatory Design

Engaging the community in co-design processes to ensure interventions reflect local needs, fostering inclusivity and ownership of public spaces.

03_Design Scenario

Creating interventions that transform vacant spaces into active public realms, promoting social interaction, sense of belonging and perception of safety.

00_INTRODUCTION

Poblenou is a neighborhood part of the Sant Martí District, at the south east of Barcelona, known for its mix of old industrial charm and modern innovation.

Historic Context

Historically, in the 12th century it was a marshy area used for cattle pastures supplying Barcelona. In the 19th century, Poblenou’s industry grew and It became known for textile printing. Workers of these places stablished in what was called Taulat or Pueblo Nuevo.

In the 70s, the textile and economical crisis led to factory closures and rising unemployment. But by 1992 for the Olympic Games some Factories and train lines by the coast were removed, new developments included Vila Olímpica, artificial beaches, and the city’s first modern coastal residences.

Poblenou Today

Today, Poblenou is part of the 22@ District, a transformative hub for universities, research centers, startups, and tech companies.

Poblenou today has good infrastructure, continuous developments and economic growth. However, is facing a silent problem. Even though the area has many positive aspects, it lacks the same level of public activity and foot traffic seen in other parts of the city. When we compare some of the most remarkable places in Poblenou to similar places around the city, we can see that in comparison, Poblenou has less people surrounding its public space.

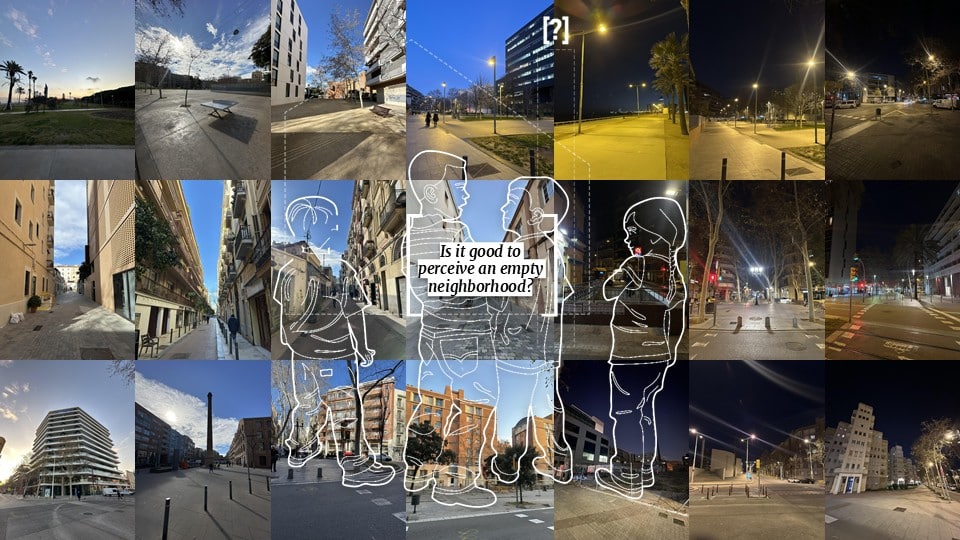

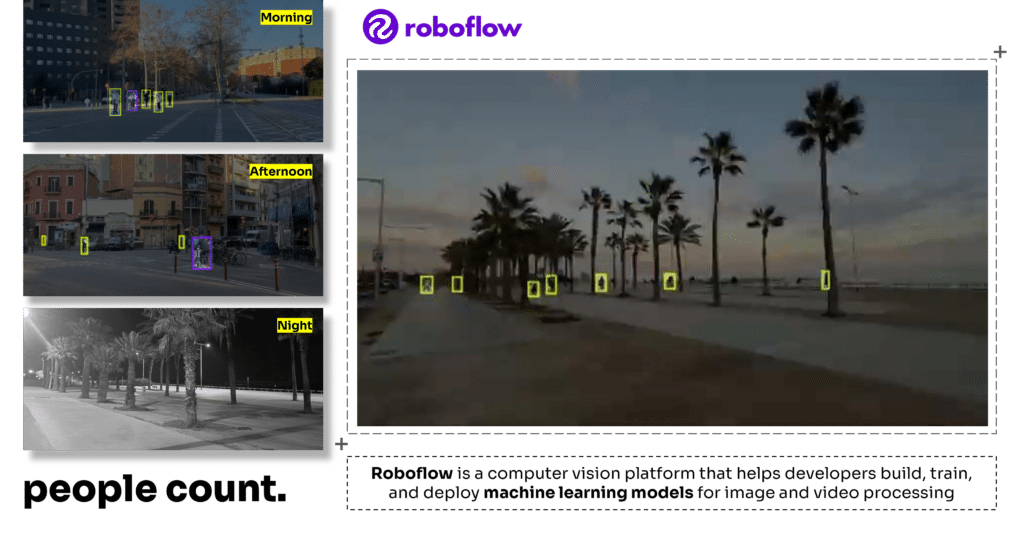

At first, we assumed that the lack of activity in Poblenou might be due to our visits occurring during working or school hours. To verify this, we decided to return at different times of the day (morning, afternoon, and night). However, we discovered that this sense of emptiness persisted throughout the day, with minimal human presence in public spaces. This experience led us to reflect on the idea of temporal emptiness in the neighborhood and question the impact of perceiving an empty neighborhood.

Based on Jane Jacobs quote from her book “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”, this should not be like this, ideally we should see people moving in the public space, we should have eyes on the street.

“There must be eyes upon the street, eyes belonging to those we might call the natural proprietors of the street. The buildings on a street equipped to handle strangers and to insure the safety of both residents and strangers must be oriented to the Street.”

Jane Jacobs

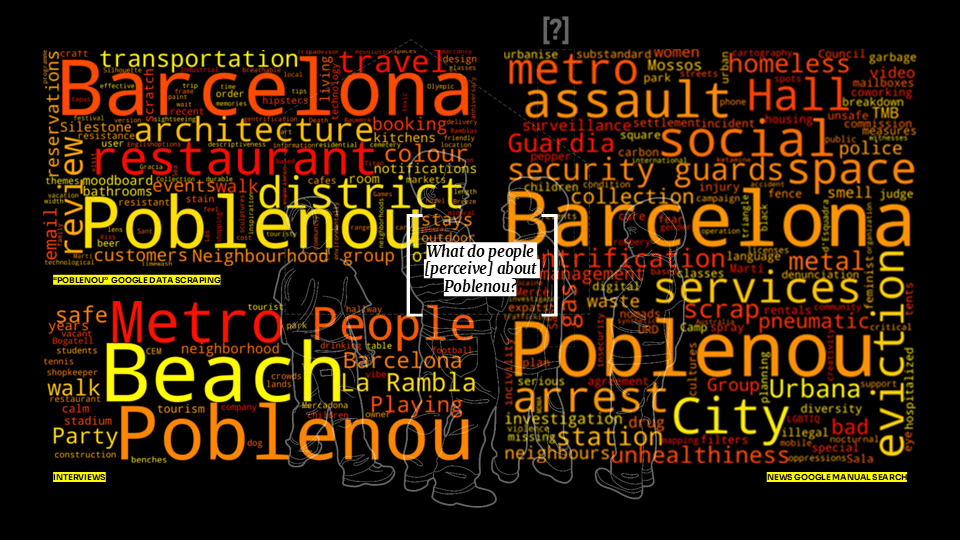

The positive aspect of Poblenou is that it is generally perceived in a favorable light. Data gathered from Google scraping and interviews show that people associate the neighborhood with its beach, shops, well-developed infrastructure, and cultural activities. However, there is another side to Poblenou, marked by incidents such as attacks on police in the metro and cases of prostitution and human trafficking. These issues highlight how the absence of public vigilance can make an area more vulnerable to problems. This reinforces the need to revitalize public spaces, ensuring they remain active and safe so that communities can look out for one another.

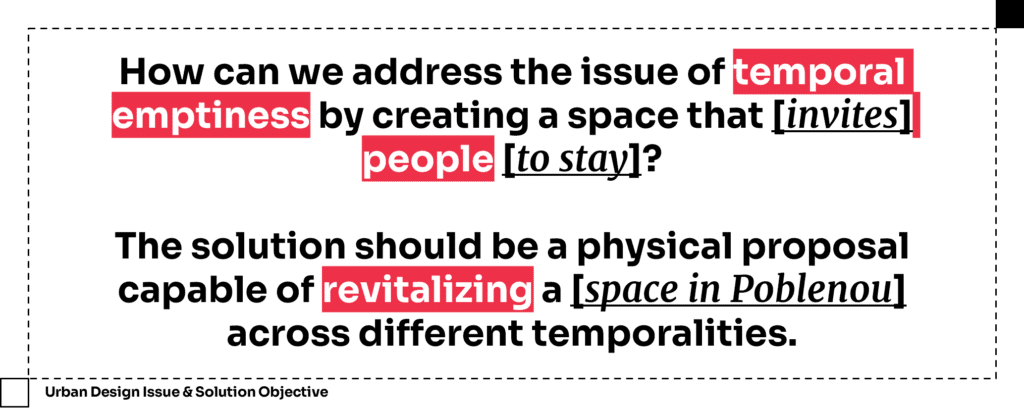

Therefore, taking into account everything previously discussed, we defined our problem statement and established our solution objective.

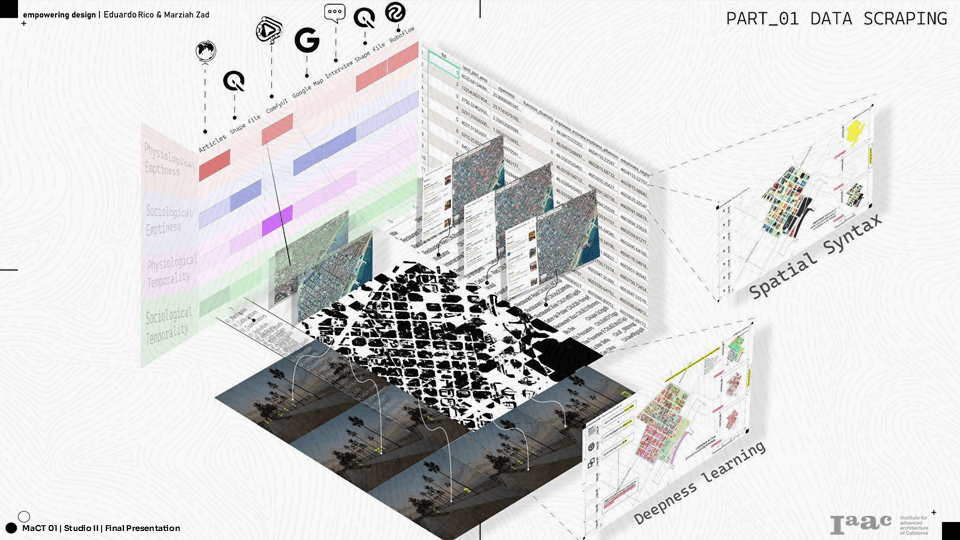

01_DATA COLLECTION & ANALYSIS

Zero down Transformed areas:

Given Poblenou’s history of significant transformation over time, we aimed to explore whether this ongoing change is connected to the sense of emptiness perceived in the neighborhood.

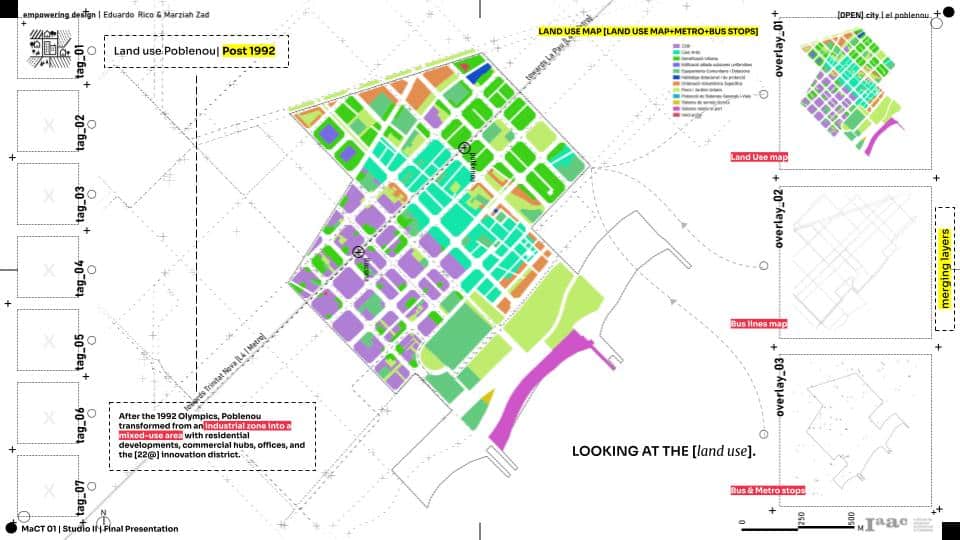

We created a base map of Poblenou with metro, bus stops and accessible points. Overlapping the data with land use provided the planning scope in the neighborhood. The 22@ district is primarily situated in the southwest of Poblenou, whereas residential areas are mainly found in the northeast. The 22@ area is more oriented toward offices and commercial activities than housing.

As a strong base to understand the transformation in Poblenou, we wanted to learn the where exactly and which buildings were transformed in Poblenou. In order to attain the dataset, we used ComfyUI Segment anything which select all the roof tops from the satellite maps. We choose two years, 2003 AND 2024 (Clearly available SAT images) and ran the segmentation.

We plotted a 25 x 25 m grid points that grabs values of roof top presence. Then we created a difference map of these grid points from 2003 to 2024 that gives us the transformed new building typologies in the neighborhood.

People Counting

Using the Roboflow, a computer vision model, we planned to map the emptiness in the neighborhood. We choose 6 different junctions in El Poblenou and visited these 6 junctions at different time periods in a day, and captured a two minute video. From the captured video, we used the vision model to count the number of people on the street.

In this way, we observed that most of the activity is concentrated around La Rambla and Pujades Street. However, at night, the level of movement drops significantly, and the neighborhood feels lifeless.

Google Maps Places

The project got an interesting turn with the google maps data scraping using n8n where we could calculate the possible functions and activities happening in each block to understand the neighborhood’s diversity.

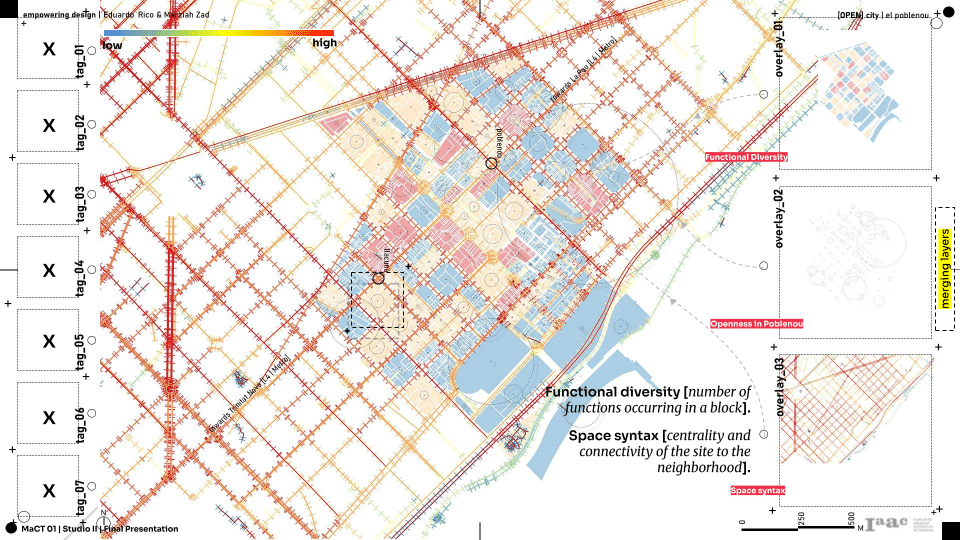

Spatial Syntax

With the overwhelming amount of data scraping, the crux of analysis opened up when every data was compiled to make a spatial syntax. Open land/ construction land in Poblenou related with syntax concludes that 22@district which was newly transformed (as per Segmentation outcome) and least activated area (as per Roboflow people counting), more number of empty lands fall in these zones and less diversity of function.

These compiled data of spatial syntax was overlapped with road network proximity to narrow down or pick a site in the new 22@ district. The openess values, functional diversity and road networking provided a open site which falls under Ajuntamento (Municipal corporation of Barcelona).

Zoning

After close study of neighborhood and their activities, we proposed five functions which can activate the neighborhood.

- Monument

- Exhibition space

- Open space

- Play ground

- Civic space

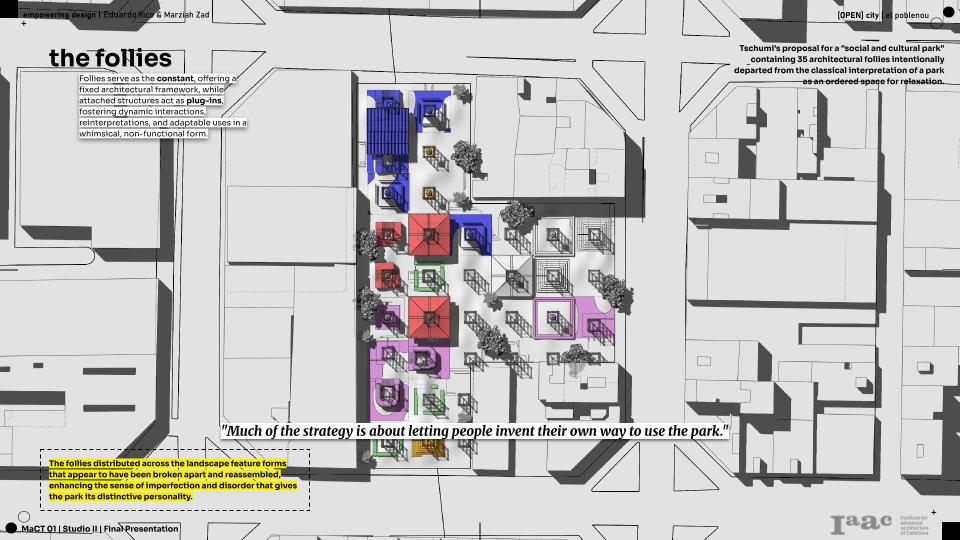

Based on the spatial syntax values, we iterated the zonings that can be transformed over the years as per the neighborhood’s needs. In order to achieve this, we used grasshopper kangaroo flux which creates a attractor points and curves to bend along.

As the zoning took a dynamic perspective, we proposed our designs to be dynamic and transformative as the functions change. In order to achieve that, we created a grid of 12 x 12 m which can transform based on functional plug-ins.

02_PARTICIPATORY DESIGN

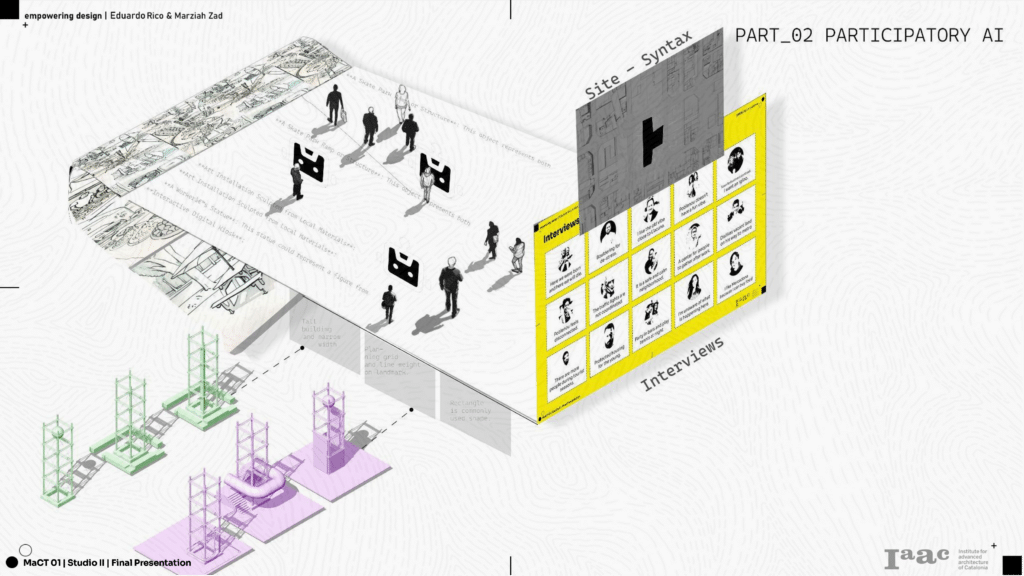

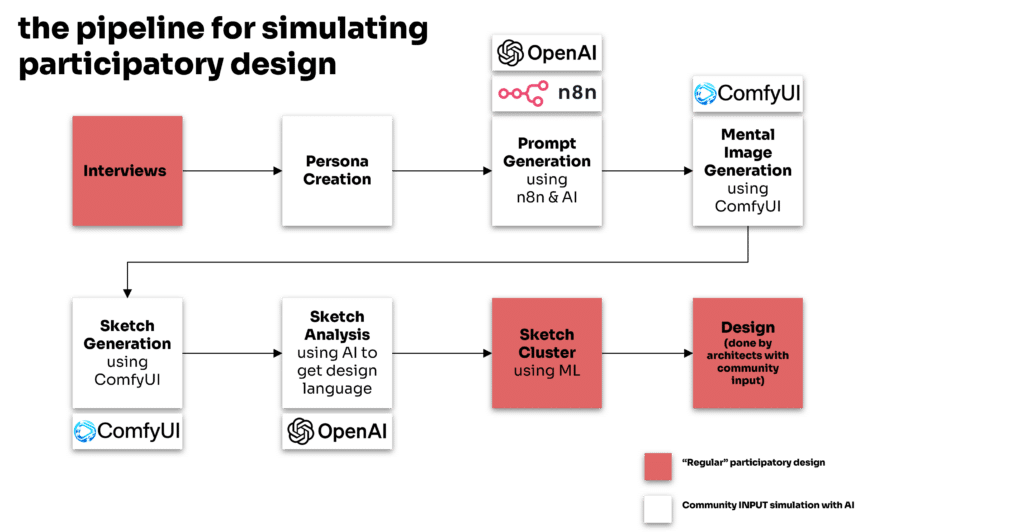

In a conventional participatory design process, we would typically engage with the community by conducting interviews, meeting with them multiple times, and asking them to create sketches with proposals for public spaces.

However, in our case, we didn’t have the opportunity to meet with people on multiple occasions. Instead, we relied on a series of interviews conducted throughout the term. To gather the necessary data for our proposal, we developed personas based on these interviews and used AI to simulate their perspectives. This allowed us to prompt the AI to generate sketches as if it were representing the voices of these personas.

We conducted a series of 15 interviews, gathering a wide range of responses and perspectives, including unexpected comments and random insights.

From these diverse interactions, we developed personas, each with a name, age, gender, needs and goals, pain points, and behavioral insights. This allowed us to standardize the information, ensuring that all 15 personas contained the same type of structured data.

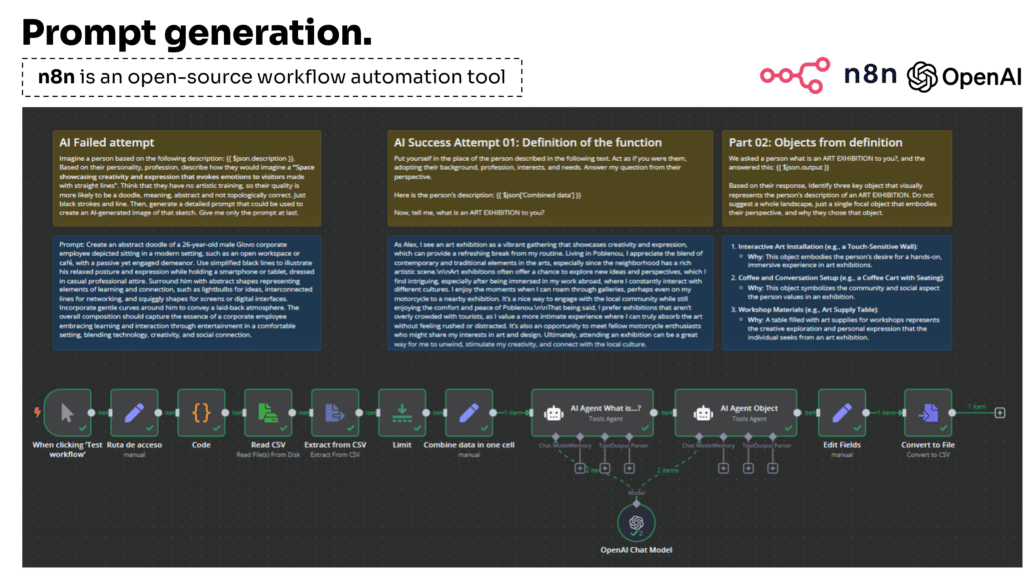

We used the personas to power an n8n workflow that leveraged AI to generate prompts reflecting community input.

Our aim was for the AI to take on the role of these personas, using the information we provided to describe five key elements for our proposal to revitalize the public space.

Initially, we encountered a challenge: the prompts we gave the AI were too long, and the responses ended up simply paraphrasing our own input rather than offering new insights. This led us to shift our approach.

Instead, we began by asking the AI questions in the voice of the personas, such as “What is a monument to you?” The AI responded with unique interpretations of what a monument meant to each persona.

We then followed up with, “Based on their answers, what kind of objects would they draw as a monument?”

This new strategy worked, AI began generating the tangible, descriptive objects we were aiming for.

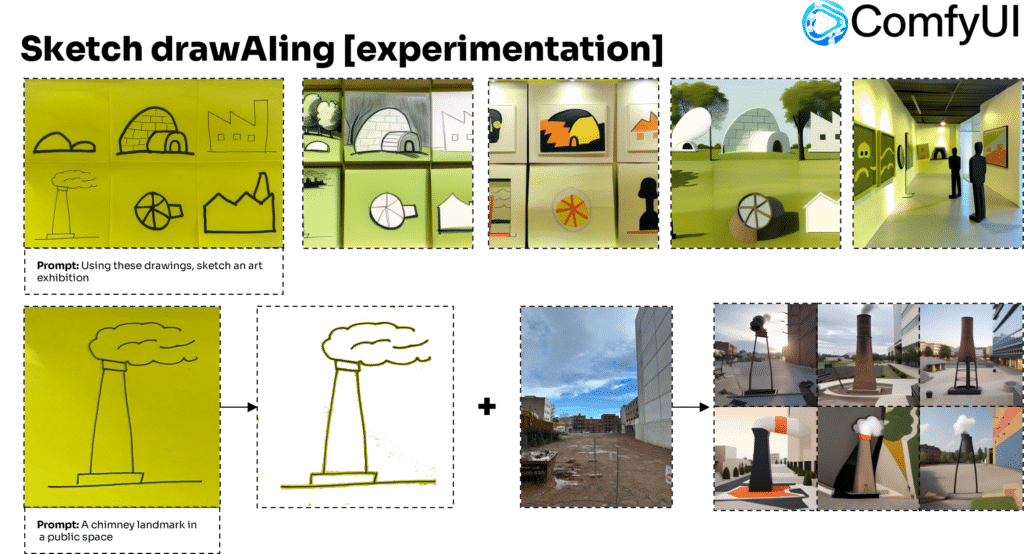

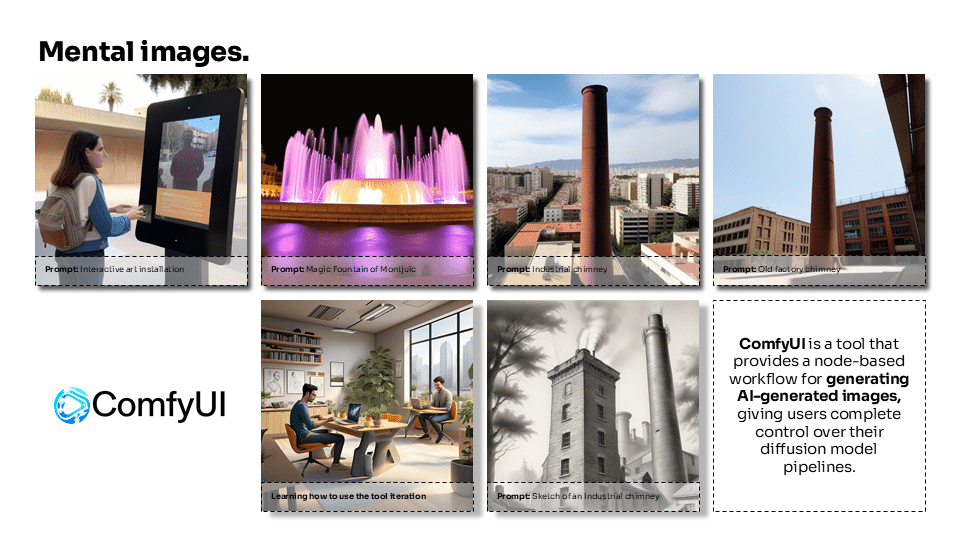

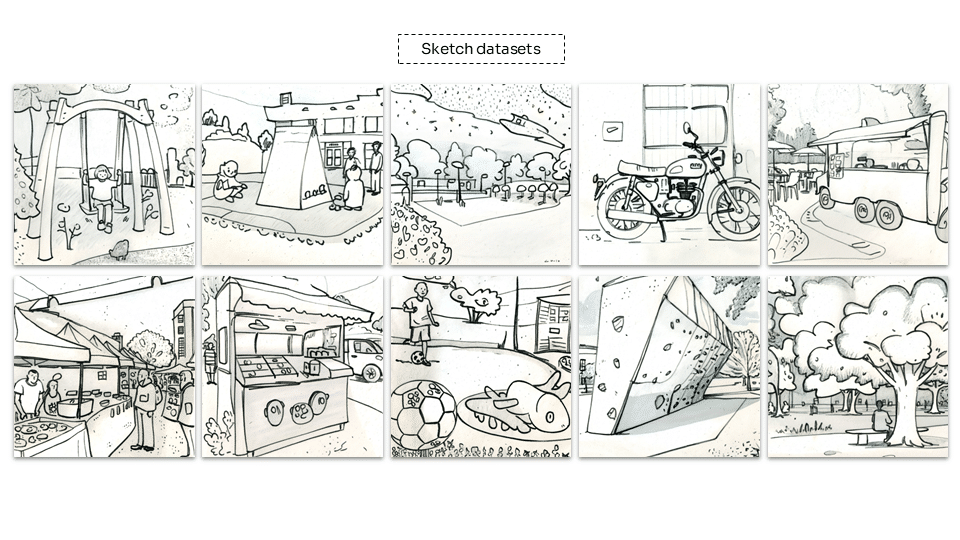

Once we had the prompts, we aimed to use ComfyUI to generate sketches based on the personas’ inputs. However, before achieving the desired results, we first needed to familiarize ourselves with the tool and its logic. Without this understanding, the initial outputs (shown in the following images) did not align with our expectations

Prompts to Images:

This task explored on learning what the stakeholder wants in this proposed site. Software like ComfyUi and n8n where connected through api-s in order to transform large number of prompts from one excel to visualisation. As an outcome, we got pretty images as per the stakeholder’s imagination. But as our participatory design process involves people with sketching, we tried to get sketches from the prompts and not fully visualised images.

On our first attempt, AI made a illustration of the stakeholder rather than his imaginary sketch and added a small sketch in photo frame. So we asked the AI to sketch “Sketch”, it gave us artistic sketchs which are more machine made and not humanly.

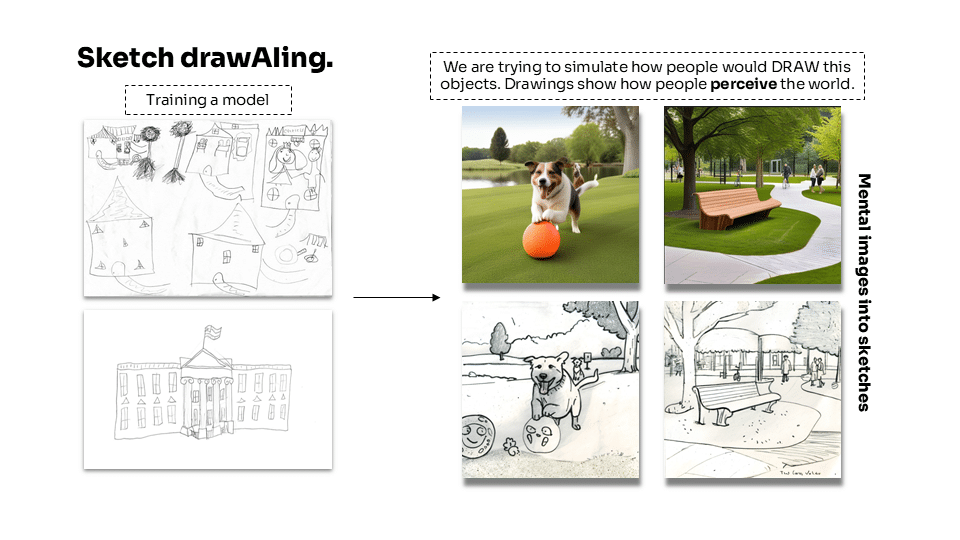

Images to Sketches

In order to achieve the sketches of desired outcome, we trained the model in comfyui to sketch by adding lots of references for each design element. Then we got some desired results as more humanly based on the human proportions and stroke styles.

Data extraction from Sketch

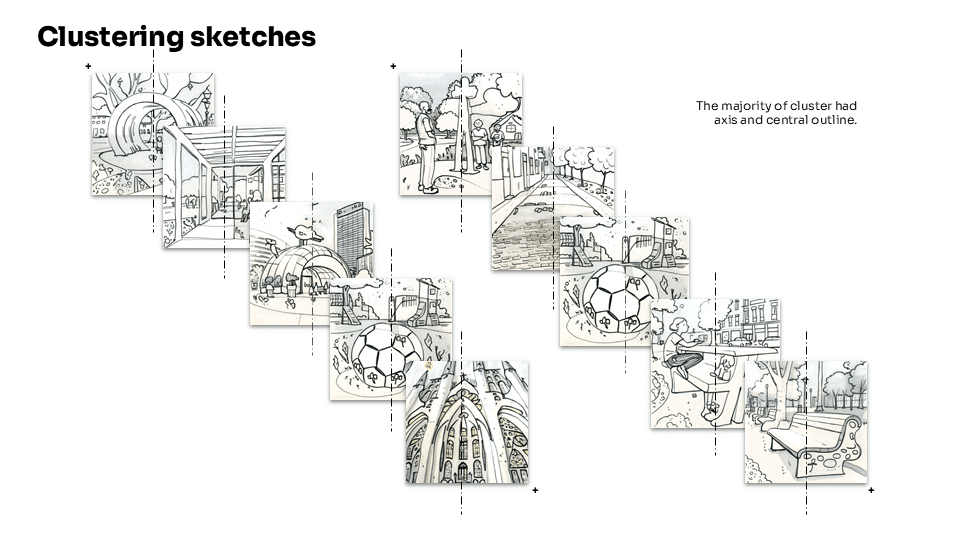

From the sketch datasets, we wanted to extract possible data sources which could help us design a proposal for the site. In order to achieve this, exploring different methods was convenient. Starting with Machine Learning, K-means clustering we used unsupervised machine clustering to classify the majority of sketches.

The results of clustering was not ample to proceed with the design proposal as the clusters were based on axis of objects in sketch.

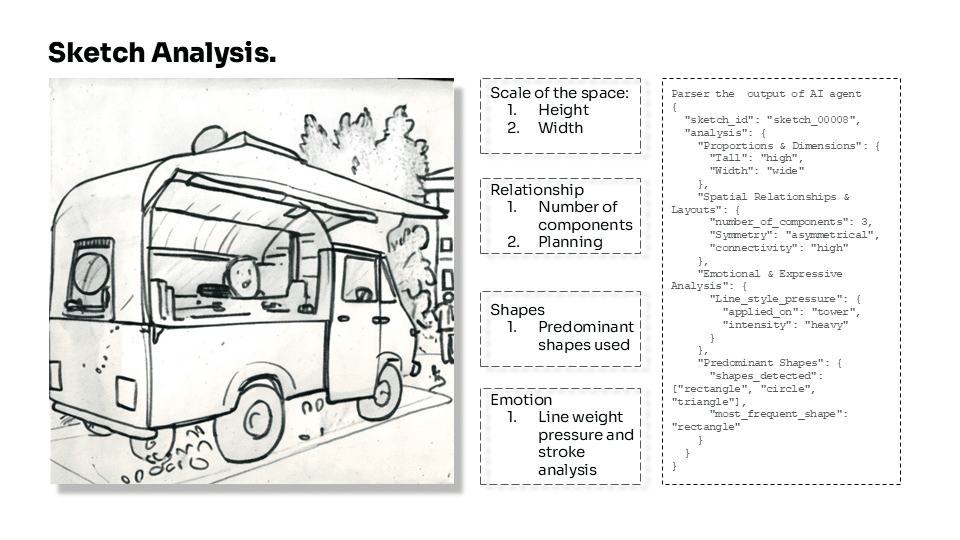

Sketch analysis

After exploring the machine learning clustering, we charted an idea of analyzing the sketches through a LLM model agent. We established a pipeline which analyses each sketch and stimulated the AI agent to analyze the following contents.

- The height and width of their proposal sketch tells us the scale of the proposal.

- Number of elements placed gives us the sense of function and planning.

- Kind of shapes and curves used to express each function.

- Last but the most interesting one, to understand person’s interest based on the line weight and detailing.

We came up with a way to collect data directly from the community while also demonstrating how their input influences our design. To do this, we developed a Telegram bot that allows users to submit a photo of their sketch proposal. The bot then analyzes the image and stores the extracted information in our database, making their contributions part of the design process.

03_DESIGN SCENARIO

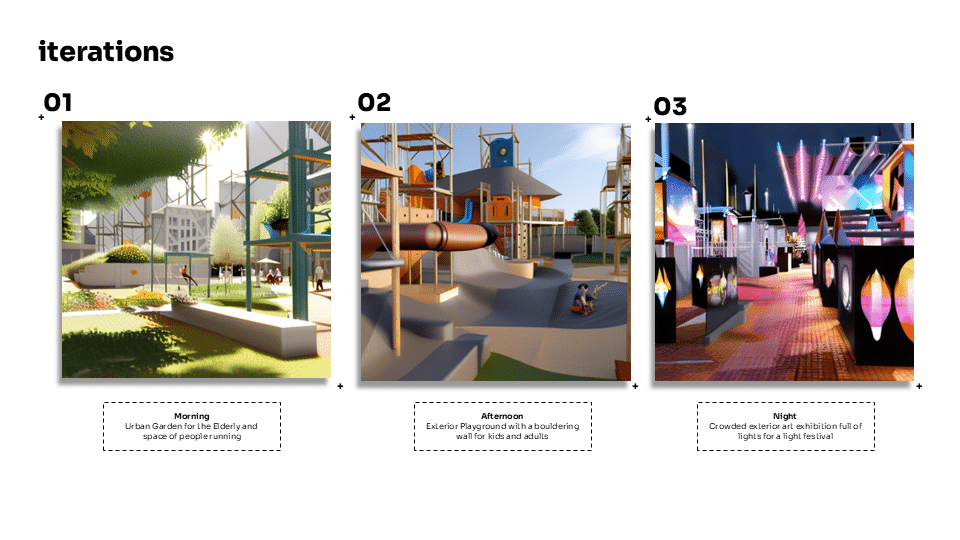

In the final stage, after developing our proposal to transform the vacant land into a vibrant public space, we captured perspective images of the model and used ComfyUI to visualize how the area would look at different times of day, tailored to the various user profiles identified in our interviews. This ensured that the people living in Poblenou could see themselves reflected in the space, with opportunities to enjoy it in ways that suit their lifestyles and daily rhythms.

From the sketch analysis, the values of each parameter where plotted with cohersion or correlation maps of each function which gives us the details for the design proposals. We experimented the scale of sketches stakeholders made for monument gives us the conclusion of “People wanted a wide structure than a tall structure”.

At the same time, we analyzed the recurring shapes in the sketches, such as squares, circles, and pentagons, and if the drawings were symmetrical or asymmetrical. The most frequently used adjective in each category helps define the character of that space. For instance, in the case of the “monument,” most participants drew a rectangular shape.

We repeated the process with other functional sketches.

In order to sum up, we clustered all the functional sketches together and we added values to concise that “stakeholders want wide structures but also for a food space, they wanted more in number whereas the other functions were less number of elements.

Visualize the data:

From the data analysis and design follies, we visualized using Comfyui adding the data as prompts and different events that can be hosted in site.

In this way, we can visualize how the space remains active throughout the day, shaped by the profiles of individuals we encountered in Poblenou during our interviews. The activities and desires they shared are reflected in the proposal, ensuring that it becomes a space created for and by the community—one that stays vibrant because it responds to the needs and aspirations of its people.

REFLECTION

To conclude our research, it’s important to acknowledge certain limitations and biases that may have influenced our findings.

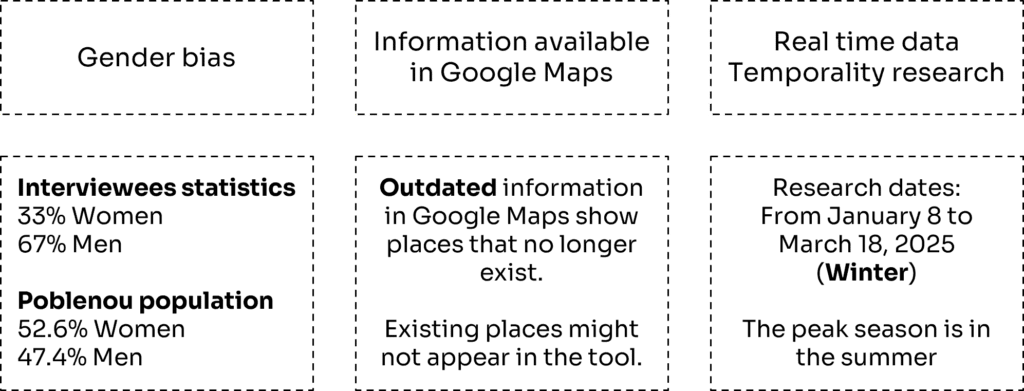

Firstly, only 33% of our interview participants were women. This was due to the fact that many women we encountered in Poblenou were either unavailable or simply not present at the time. Ideally, we would have interviewed men and women as the same percentages of the real demography in Poblenou.

Secondly, some of the data gathered from Google Maps may be outdated. In some cases, locations listed as open no longer exist, and some businesses or places may not appear at all if they haven’t been registered on the platform. This means our maps might not fully reflect the current state of the neighborhood.

Lastly, our research was conducted during the winter. Based on feedback from locals, Poblenou is much more active during the summer, which is considered its peak season. As a result, our observations might differ from what could be found during those months. However, due to time constraints and the scope of our project, we were unable to conduct research during the summer season.