Urban Security & The Public Space of Foreigners

Introduction:

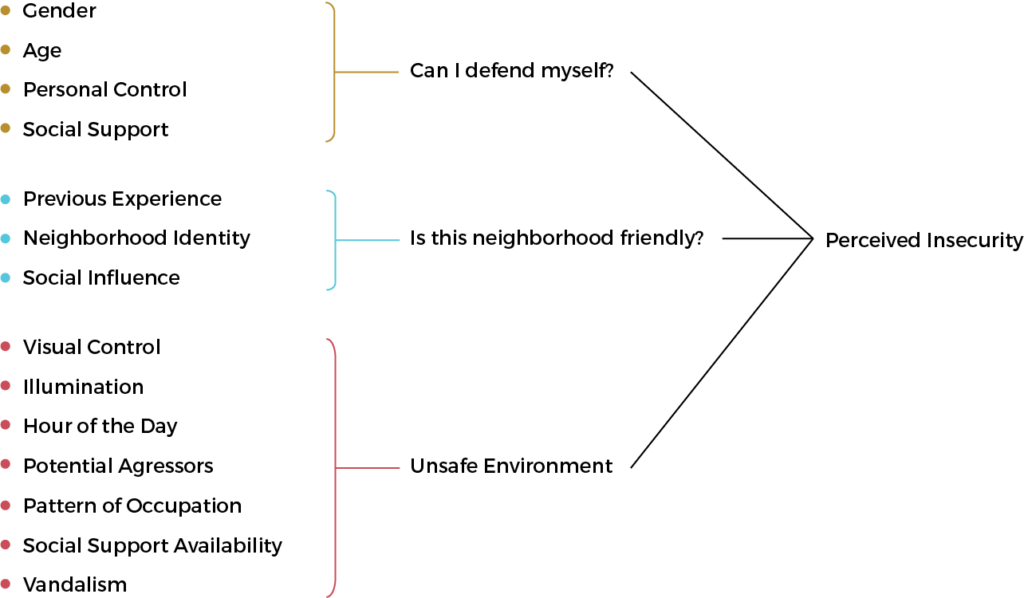

Is it safe to travel to Europe? Depends on who you ask, you might be told that your concern is almost a total nonsense, or be assured that it is a certain lost of phones and wallets. This is rendered by the fact that although the statistic of crime in a community may be relatively low, fears caused by the news of separated incidences around the neighbourhood can spread among public without actual experiences. For cities that has a high flow of tourist population, it is only reasonable that such phenomenon can also be observed among the sparsely distributed community of this particular group. An internet search using related entries yields results that prove the relevance of such concern. Notably, some search results points out specific categories that one should be aware of as tourist. These mainly include petty property crime such as pickpockets and hotel crime. Conversely, the committer of such crime also tends to target the tourist population, and it is very likely that they have chosen this “career” because of the high “opportunities” provided by the intense tourist presence. This factual positive relationship between tourist concentration and the soaring of crime rate has been statistically proven by many researchers. As architects and urban designers, the general population’s wellbeing in their residing neighborhood is naturally one of our major concerns. Taking Barcelona as a typical European destination for overseas visitors, this project intends to carry out a systematic study of the real state of affair in the city, and thereby attempt to experiment with a methodology that might assist in improving the public sense of security at the contested sites where concerns are needed to be addressed.

Project Aim:

The project aims to analyse the degree of responsibility of urban planning behind the cause of the current state of affairs, and to produce an intervention that best remedies where this responsibility might be failing as urban planners.

Methodology:

- Identify the correlation between tourist concentration and crime rate.

- Identify one specific townscape where crime and tourism overlaps.

- Analyse the urban elements that may have potentially contributed to the insecurity.

Framework & Prospectives:

- More tourist means more activities. More activities means more security concern.

- Tourists are foreign, unfamiliar with the local condition, and are less likely to seek help from the local police.

- Criminals are not necessarily local as well, views tourists as opportunities, professional occupation targeting specific urban areas.

- Property crimes (thefts/robbery) constitutes the majority of the reported crime.

- Perception of crime can easily become much higher than actual crime rate.

Thesis Statement:

Tourism, Crime, & Urban Security experiments with the possibilities to enhance public security and wellbeing at an urban design level by methods such as spatial management, the friendly deployment of barriers, and encouraging mutual support, reducing costs and repressiveness in public space that came along the continuous upscaling of policing, creating a positive environment that contributes to the healthy coexistence between foreign visitors and the local residences.

Case study of Barcelona:

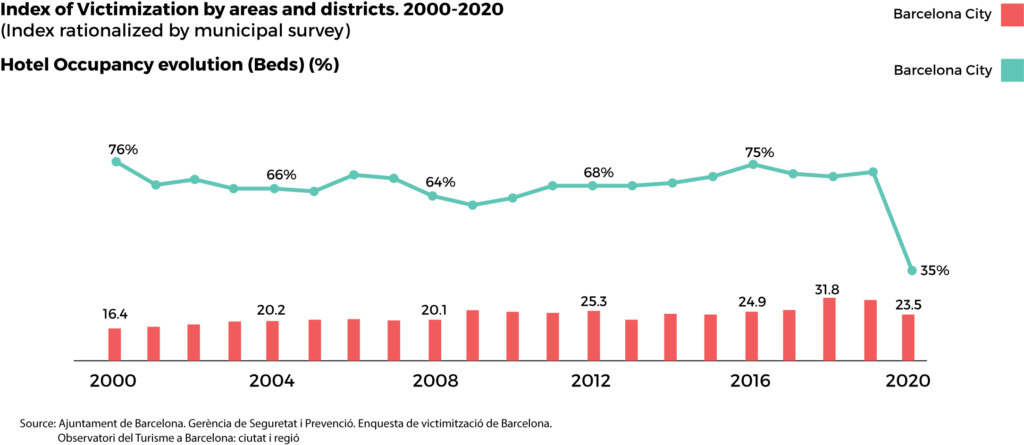

As a city that has established for itself a strong dependence on tourist economy, Barcelona received more than 29 million visitors (by hotel stays) in 2022. Tourism economy in Barcelona witnessed a stable growth in the past few decades, which came alongside a stable increase of crime rate. The relation between these two figures are no mere assumption: the rising level of victimazation dropped alongside the drastic decrease of toursit activity in 2020, after the COVID mesures went in effect. On the other hand, a study conducted prior to 2014 states that the fear of crime in Barcelona has been a prolonged issue since before the drastic rise of victimization index in the following years. An important observation made by the same study states that the social anxiety among local population could have been the outcome of uncertainty towards the soaring foreign population, which went from 2% in 1998 to 18 percent in 2012. The anxiety towards the frequent appearance of large groups of strangers, also amplified by reports of a mere few real cases, could spread incoherent fear among the local population.

Compare to data from online survey on the perceived security level of security, Barcelona is certainly on the top of the list.

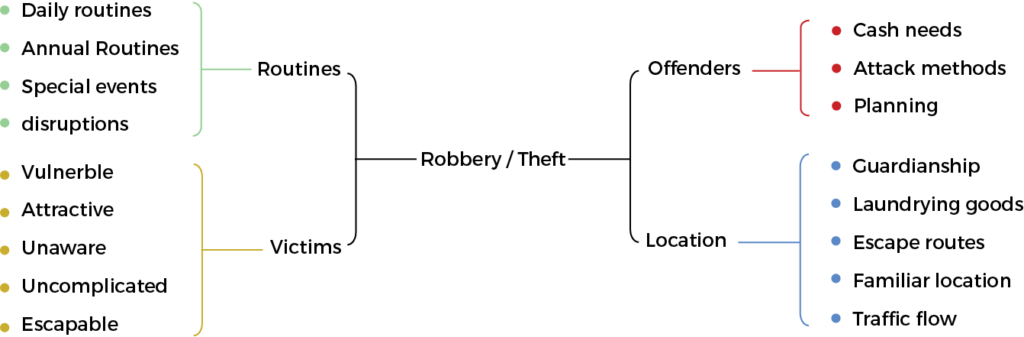

What makes tourists easy targets? The simplest reason is that tourists often carry valuable belongings such as cameras, phones, jewelries, and cash; but more importantly, their pattern of behaviors often differs obviously from the local population, thus making them easily identifiable as valuable targets. The Problem Oriented Guides for Police published by the U.S. Department of Justice has pointed out following scenarios regarding street robberies:

“Street robberies occur when motivated offenders encounter suitable victims in an environment that facilitates robbery. A street robbery problem emerges when victims repeatedly encounter offenders in the same area. ”

Meanwhile, the Guide also points out that:

“…tourists are vulnerable because they are more likely to be relaxed and off guard, and sometimes careless while on vacation.”

It is also claimed that tourists are less likely to report a crime, which corresponds to the results of another study conducted in Barcelona. All these traits contribute to motivate the offenders to target tourists, and the confirmed likeliness of success promotes such activities to emerge into repetitive and even organized offences. The Guide also reminds us: “Furthermore, media coverage of crimes against tourists often tends to be out of proportion to the actual risk, having a profound effect on public perception of safety at particular locations.” In Barcelona’s case, this observation is manifested by the notoriousness of El Raval.

El Raval in Media:

Barcelona’s district of El Raval has, for a long time, suffered from the reputation of being the most dangerous part of the town. Pickpocketing, robbery, drug dealing, and prostitution plague the alleys of the congested medieval side wing of Barcelona. Although it was mentioned to testify what the U.S. policing guideline states as the impact of media’s over-coverage of crimes against tourists, angry testimonies of those who actually suffered from property lost or personal harm are even more responsible for reassuring skepticisms towards every street corner of this otherwise quite acceptable neighborhood. Posts from personal accounts on platforms such as TripAdvisor or Reddit relives the details of their victimization with vivid words and strong opinions, which are hard to tell if there is any exaggeration due to anxiety and excitement.

El Raval in Data:

In order to obtain a clearer grasp on the actual circumstance of El Raval, data from research papers and government publications regarding the relevant information in the city of Barcelona has been put into visualized comparison. Hopefully, this could help to find out some insights, or confirm some assumptions behind El Raval’s low level of perceived security. Starting from the tourist heat map and tourist attractions.

Here we see that El Raval and the central Eixample are the two neighborhoods with highest violent crime index. These areas coincide with the tourist heat map, but somehow avoids the central venues of the hottest tourist activity. The following graph shows the extent of tourists occupation in each neighborhood by the percentage of tourist bed to the total bed count. This area meets the hottest zone of tourist activities, and is surrounded by the zones with higher crime rate.

These graphs indicate that El Raval is the neighborhood with highest perceived rate of crime. Interestingly, the central Eixample which also has a high rate of violent crime seems to be much safer in perception. Meanwhile, the other two neighborhoods in the Old Town are all perceived as rather unsafe despite having lower crime rate.

In the cited research, the author compared the effect of police presence to the perception of safety in a specific location. The graph here shows that police presence is much less frequent in El Raval than the adjacent neighborhoods. Although this data was gathered in 2015 and, according to the official publication cited previously, the police activities on the streets has seen a significant increase in the past few years, the author still offered some insights with their observation. Not considering the possible ambiguities behind the lack of police presence in El Raval back in the days, we can at least say that the police were much less motivated in stopping individuals in El Raval, especially in comparison to the other two, more tourist-rich neighborhoods of the Old Town. While the possible reasons for El Raval to be less attractive to tourists must be discussed in the following sections, here we can make a quick comparison of the police-crime-tourist data. Although one may observe that the low level of perceived security could be related to the lack of police presence in the region, since the other neighborhoods with high level of police activities are generally considered to be much safer, the author of the sourced research paper has pointed out that police presence may in fact cause negative impact to those who have recent encounters with actual crime. This is probably relatable to the negative impact of CCTV on crime risk perception: “symbols of security can remind us of our insecurities.” To put more rationally, outside forces that help us to maintain security could have the effect of reducing personal sense of responsibility and awareness, thus increase the possibility of victimization, while the level of anxiety is also risen as we realize that there is a necessity of constant police surveillance. This observation may seem self-contradicting, but is a rather realistic depiction of the complicated human psychology under the even more complicated social environments. The following graphs led an insight to one of the most disputed traits of El Raval when its crime issue is under discussion: its demography.

The last two graphs indicate the distribution of foreign-born male residents in each district and the distribution of education level among the general population, which shows a concerning degree of correspondence between the two. The negative impression towards immigrants is a problematic, yet unfortunately all too realistic factor that generates a perception of potential risk, especially among foreign tourists. From what we have discussed above over the factors that generates the senses of insecurity, we can assume that this impression of risk is very likely to be caused by obscurity between culture, a type of insecurity due to uncertainty and suspicion towards a community that is excluded from what we are used to. While it might be easy for those tourists who share a common language, or even a common nationality, to feel quite at home under this kind of environment, the apparent perception of economic underdevelopment and incivility around the streetscape, such as graffiti and litters, causes a natural sense of anxiety to those who came to expect good sights and friendly services. It is thus important to consider a redevelopment of these districts with special supports provided for immigrant entrepreneurs and encourage more unhindered contact between them and the visiting tourists.

So far, the observation provided by this series of maps can be described as follow:

- 1. The concentration of tourist activity is related to various other urban factors, but mainly with the distribution of attraction sites.

- 2. A strong positive relation between tourist concentration and crime rate.

- 3. A negative relation between tourist concentration and police activities.

- 4. A distribution of perceived crime rate that normally scales with the actual crime rate, but is lower in Eixample and higher in the entire Old Town district.

- 5. A very unfavorable statistic of education rate for residences who dwell in the Old Town, which are the most tourist-rich neighborhoods and are mostly occupied by foreign residents.

What are the Insights?

As of El Raval specifically, we found that:

- – It has a high level of perceived crime rate.

- – It has the highest level of actual crime rate.

- – It is adjacent to the hottest tourist zone, but tourists seem to have less interest in this neighborhood than the other ones of the Old Town district.

- – High percentage of immigrant popula tion.

- – Low level of education.

If put into cross-comparison with the other neighborhoods of Barcelona, especially the ones that are also frequented by tourists in the urban center, we can try to understand why is El Raval is special:

- The Gothic neighborhood: which is the actual nucleus of the ancient Barcelona, is also perceived as unsafe, but is much more popular among tourists than El Raval. Likely due to the fact that this is also the location of the city’s government, police presence in this immediately adjoining neighborhood is significantly higher than El Raval, separated only by a few alleyways. It also has a low level of education, but has a significantly lower percentage of foreign-born residents, likely due to the fact that this area is mostly occupied by temporary visitors. It is hard to tell a strong difference between this area and El Raval other than the higher concentration of attraction sites.

- The central Eixample neighborhood: also has a higher rate of crime, but has a very low level of perceived insecurity. It is also home to some of the hottest tourist attractions, with also a large percentage of tourist accommodations. The concentration of immigrant population is low and education level is high, and police do not frequently stop people in this area. Besides those quantitative data, the urban landscape of Eixample is much more open and aiery, which is very likely a source of perceived civility and security. Compared to El Raval, the main differences here seem to be the townscape and the demography.

Putting the above observation together with the elements of security perception, which we have discussed earlier, we can see now that the deteri-oration of El Raval’s security level can be accredited to the following causes:

- – High level of tourist activity has caused a target-rich environment for the offenders.

- – Low level of police activity has reduced the potential cost of crime (according to the city council, this situation has been altered by increasing police activity in the past year).

- – Relatively lower density of tourist level room for offenders to maneuver.

- – Proximity to the more concentrated area sometimes cause tourists to lower their guards when they enter this somewhat quieter environment, as people are generally more worried of pickpockets in crowded areas.

- – On the other hand, as they wonder deep into El Raval, the apparent signs of incivility (litters, graffiti, and suspicious groups of individuals) could cause them to feel anxious again.

Commenting from the first-hand experiences of the author during the field survey, it can also be said that the appearance of El Raval’s streetscape can also lower the awareness of a tourist, since they are likely expecting to feel some medieval vibe around the area. Negative sensation may also arise as they discovered that El Raval somewhat resembles an underdeveloped ghetto rather than a medieval tourist town (like the adjacent Gothic neighborhood).

In order to further understand the issues with El Raval, the next section will be dedicated to a brief history of El Raval’s development. As a part of Barcelona’s Old Town, why is it different from the Gothic nucleus, and why are tourists way more interested in the latter?

On the other hand, as we have now observed the relation between the concentration of tourist activity and the concentration of crime, we can conclude that the lucrative tourist industry is indeed capable of raising both the legal and the illegal businesses that feed around them. As town planners, measures should certainly be considered to mediate these problems, as they negatively affect the healthy growth of local economy and the wellbeing of the regular citizens. At this point I would like to revisit the thesis statement of this project:

Thesis Statement:

Tourism, Crime, & Urban Security aims to boost the perception of safety during tourists’ visits at attractions with high victimization rate.

El Raval in History

After investigating the state of affairs in today’s El Raval it would also be necessary to have an understanding of its historical development. Although some may think that it is better for the introduction of historical background to be placed at the beginning of the story, in this case it is more important to first understand the problematic that is widely relevant to many tourist cities in Europe. That is because the main reason behind this phenomenon is also widely relatable to many other cities in Europe and some other parts of the world: the making of a tourist city from what used to be only regular fabrics.

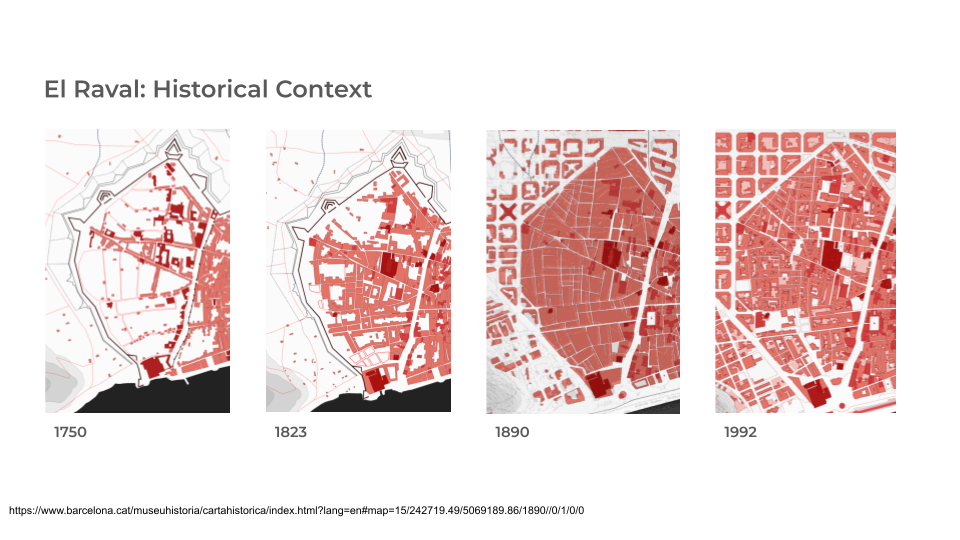

As mentioned, El Raval is a part of Barcelona’s historical nucleus that seems more underdeveloped than historical. This is due to the fact that although El Raval has been a part of the ancient Barcelona since as early as the 14th century, most of its fabrics were only built up during the 18th century. Initially, it was populated by the displaced residents of the Ribera district, which was demolished in favor of a military citadel under the order of the newly crowned Felipe V, a move that is understood as the retribution for the city’s support to his opponent during the Spanish War of Succession. From that point on, El Raval’s image as home to the displaced working class continued to the modern days, only that the distance of displacement is expanded from within a city to across the oceans.

Scholars sometime characterize the architecture of Barcelona into three periods: the Gothic, the Modernist, and the contemporary. This wide range of variety is considered as an advantage for the city’s marketing of its tourist image under the competitive environment of the old European cities. El Raval, on the other hand, is on a quite awkward position that fits into neither of these three categories. Its streets are as narrow and organic as a medieval town, yet the residences are mostly constructed in a pre-modern time under repressive condition, only a several decades older than the Modernist blocks of the Eixample district. The tendency of over construction during the industrial age was mediated by the openness of Ildefons Cerdà’s masterplan in the Eixample, but is worsened by the narrow alleys of El Raval. This has caused an inherent disadvantage when the neighborhood needs to be integrated into the new image of Barcelona as a welcoming city that opens its arms to the global visitors.

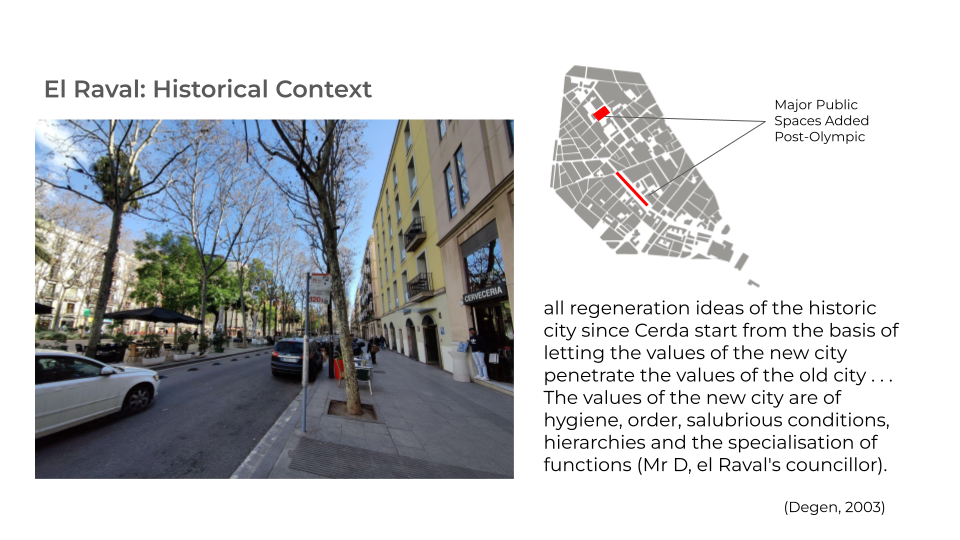

In a paper published in 2003, Monica Degen described this kind of urban reforms as “fighting for the global catwalk,” a trend motivated by the rise of global leisure business. Degen made a comparison between Barcelona’s El Raval with the Castlefield neighborhood of Manchester, England, as both of them are seen as typical examples of how the public life of a socially underdeveloped domestic landscape could be altered to serve as a showcase of the city’s reclaimed identity to the global audiences.

Degan observed that the reforms of El Raval back in the days was aimed to “homogenize” it with the rest of the city, in a way that the uniqueness of its physical space is preserved as the local population became mixed with the rest of the city. The new public spaces such as the Museum of Contemporary art and the public spaces for leisure were meant to present El Raval to a brand-new type of audiences. The local population were considered as elements of instability and potential risk of crimes, while the prospective user of these new spaces, the educated middle-class who find interest in the unique vibe of El Raval’s unexpectable physical space, were imagined to take up the public activities and suppress the actions of incivility practiced by the local residents.

Degan then quote the words of a planner who was involved in the reform programme of El Raval:

“[The criminal activities] are happening because one type of people occupy [el Raval]. . . . When they start to mix they will be forced to disappear. Because people won’t allow that somebody shoots up [heroin] in their door entrance.”

The reality is that the undesired “one type” of people refers exactly to the immigrants from Africa and Asia, who made up of a significant part of Barcelona’s labor force. As stated before, El Raval was a once-vacant part of Barcelona’s old town with little significant sites, save for a few monasteries, and was populated first by the displaced workers from Ribera. The number of workers living in this area grew rapidly since the early 19th century, as the industrial revolution demanded more workers, first from other parts of Spain and then from the third-world countries. Those who have basically made El Raval to what it is are now considered uncivil and are needed to be displaced again in order to make their neighborhood’s unique appearance exploitable as tourist resources. On the other hand, the reform was only completed in a piece-meal fashion, with only the namable few public sites “regenerated”, while most of the narrow alleys were left untouched. Unfortunately, the dreadful housing condition and the lack of real historical vibe of the Gothic district have offered little interest to the targeted middle-class population, who would only visit El Raval as passer-by at those designated public spaces.

It should be easy to understand the high level of criminal activities in El Raval at this point. Although it is never possible to say that there can be a clear-cut answer of why, since society always ferment with a million possible combinations happening and tangling at the same time, the amount of information we have obtained so far makes it safe to reach a rational understanding of the situation based on the previous diagrams on the motivation of crimes and the perception of risk. From this point on, the project will start to discuss a potential set of solutions that may bring positive changes to El Raval’s state of affairs, taking lessons from the previously discussed design-security theories and the implemented interventions in this neighborhood at the same time.

Identifying Crime Scene

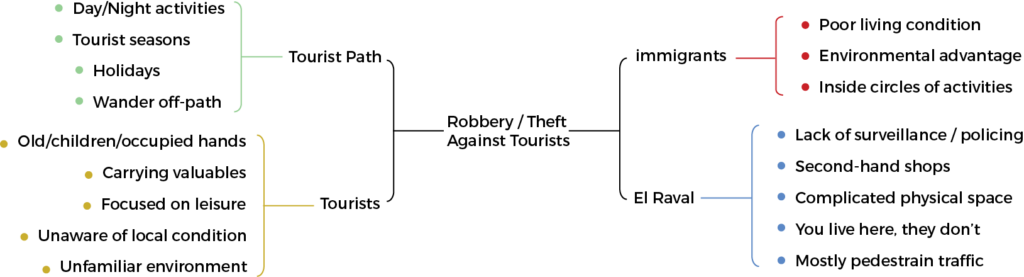

In order to start discussing the potential sets of interventions that may help to improve the level of urban security in El Raval without making the same mistake of excluding its existing social structure, it is necessary to first identify a specific set of physical spaces. This should be done based on finding the typical condition of sites where crimes are most likely to occur. Let us recap the following points.

- Crime rate in El Raval is associated with tourist activities

- Tourists mainly occupies the adjacent neighborhood, only visit El Raval at specific sites of interest.

- El Raval’s local residents generally live under undesirable circumstances, while its demography allows for the creation of small, closed circles that lacks community connectivity with the other occupants.

- El Raval’s physical space is usually narrow, dark, and irregular. Each of these four factors matches to a category of the previously introduced diagram of street crime. As a specific type of victims, tourists in El Raval makes routine visits along specific passages of El Raval, making lucrative opportunities for offenders with motives to conduct their “businesses”, and use the irregularity of the physical space to setup both the element of surprise and the escape road.

If we utilize the previously-shown diagram to analyze the case with El Raval (Fig.32), it is possible to make a direct substitution of each category that contribute to the final moment of an offence with a specific trait of El Raval’s tourist sector. Not only that the tourist are traditionally easy targets for offenders, given that they often carry cash and valuables and are unfamiliar with the local environment, their pattern of behavior in El Raval is also highly predictable. Unlike the nearby Gothic district, where tourist may take every single minute path to both get to the densely scattered sites of tourist interest and to experience the medieval atmosphere, tourists in El Raval often only for the few sites that interest them. This is not only making it easier for offenders to identify their targets and plan their action, but also allowed them to use the unvisited alleys as their escape. As of the offenders, it pains to acknowledge the reality that they often came from a specific demographic group, but it is only understandable if one considers the desperateness of their living environment and economic status. What could be said if they even hold resentments against those tourists, who are wanted by the city for the economy, while they are the unwanted margin at where they have to make their own life?

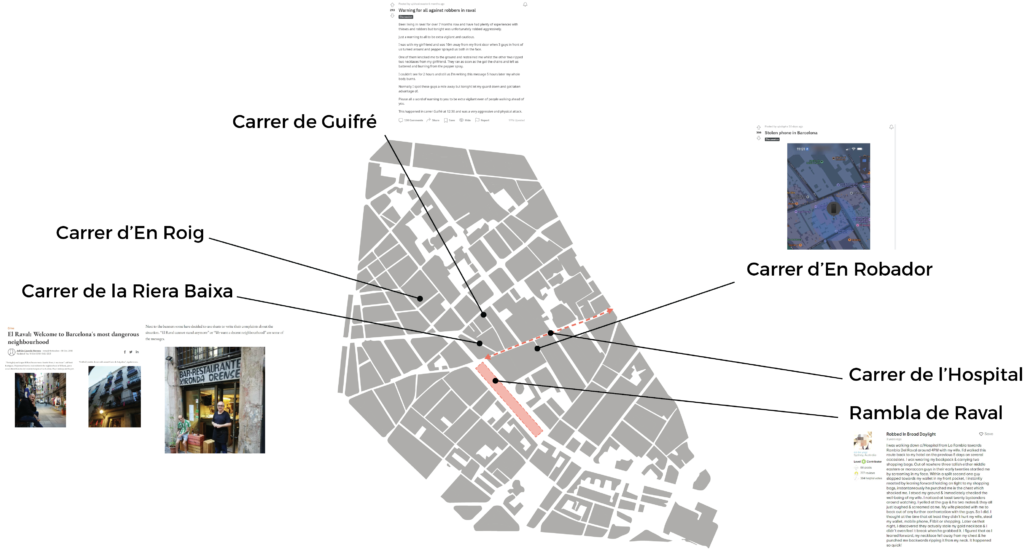

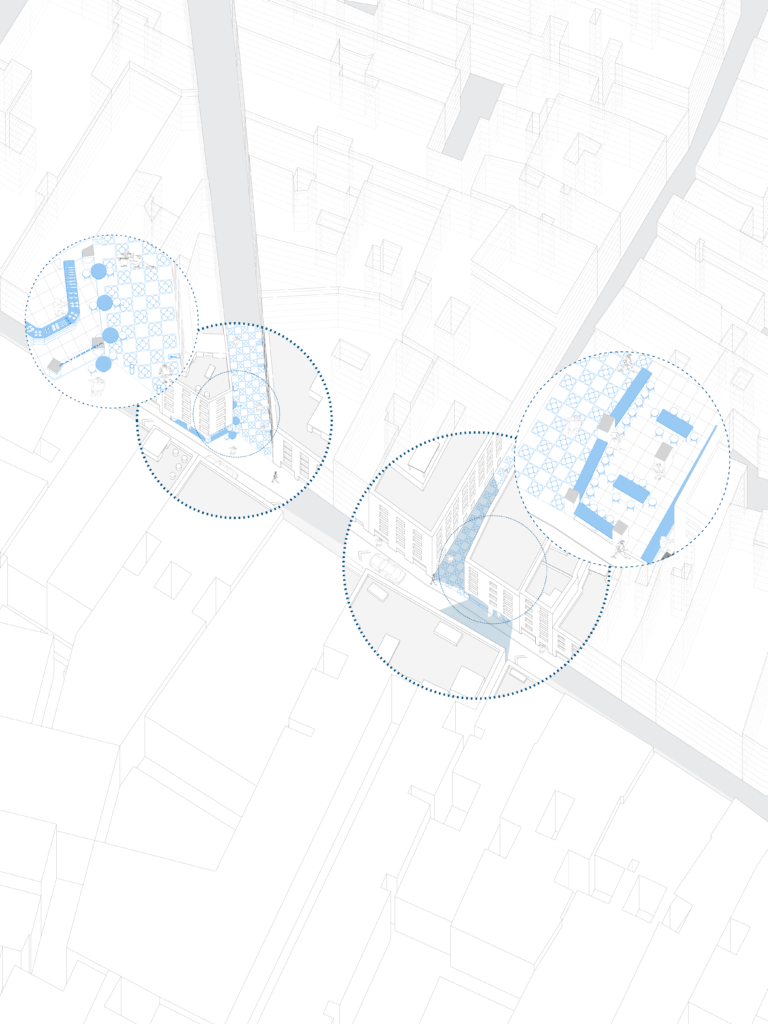

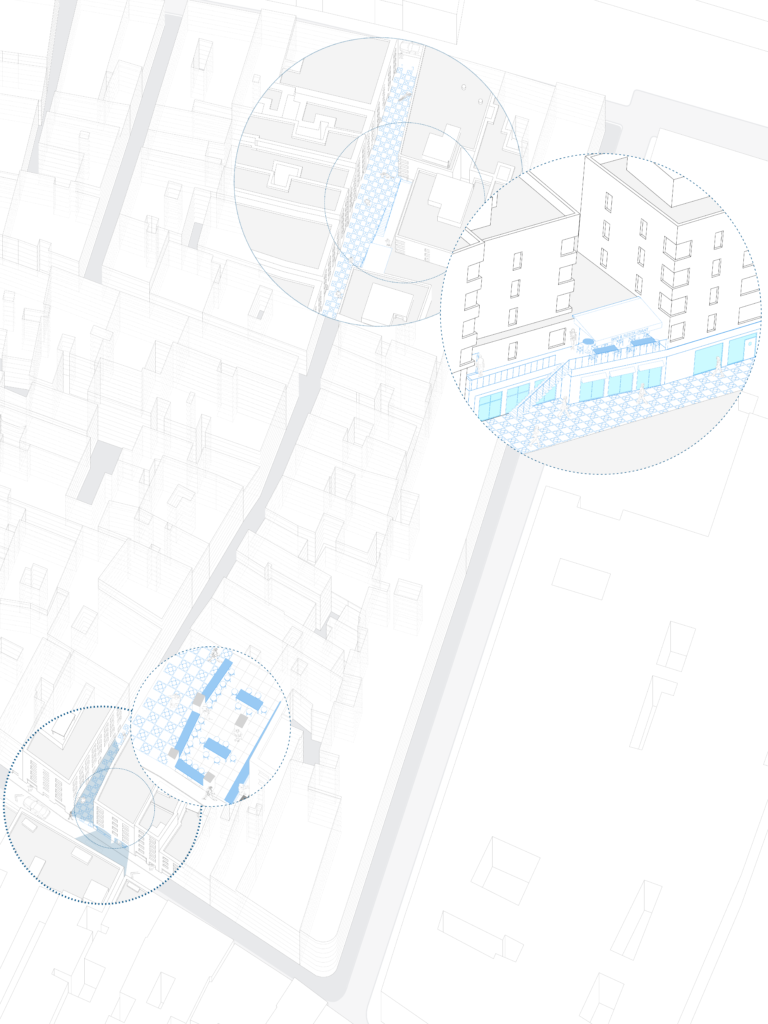

Sites of Intervention

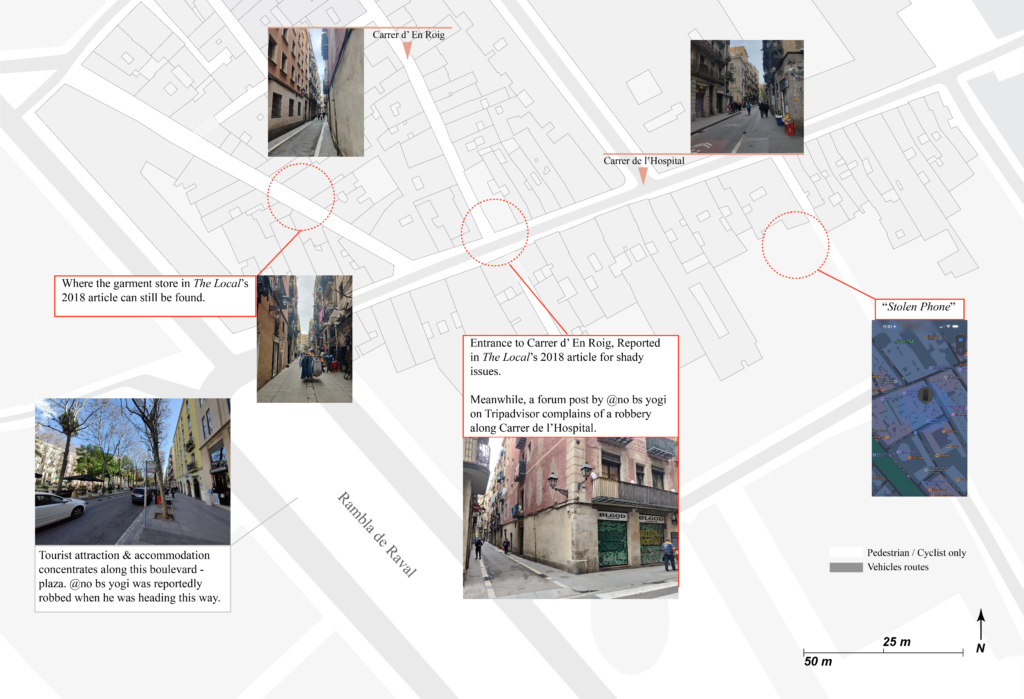

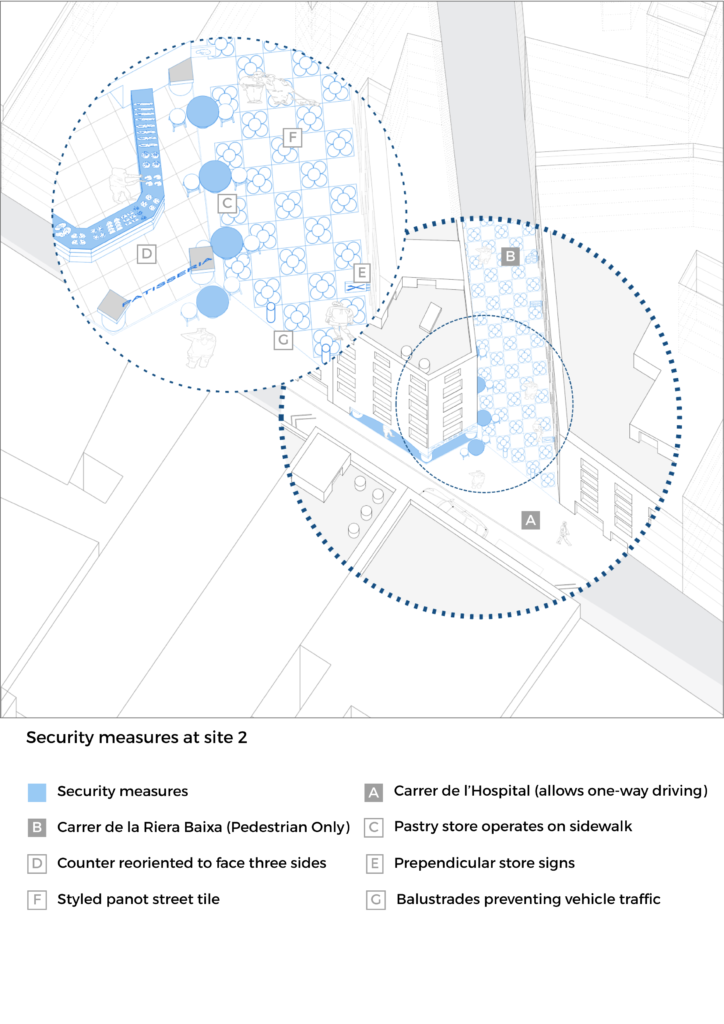

In the previous chapter, we have presented a few examples of crime cases and testimonies of victims. In order to find out a specified site for intervention, the distribution of these cases is mapped and analyzed based on the diagram of street crime. It is concluded that there exists a concentration of both reported crime cases and apparent complains of public safety along the Carrer de l’Hospital, especially between its joint with Carrer de la Riera Baixa and Carrer d’En Roig. We then proceeded to zoom down into its plan and investigate its physical characteristics.

In the testimony of a user named no bs yogi, the victim described his encounter with a group of hooligans who walked up on him and took his gold necklace in a violent and mischievous physical assault.41 It is observed that the location of this incident, the Carrer de l’Hospital, is a direct access between La Boqueria food market on La Rambla and the Rambla de Raval, which accommodates a concentration of hotels and was where the victim was heading towards. The case includes almost all of the elements stated in the street crime diagram: Along the route of routine where tourists often travel, a victim with his hand occupied by shopping bags and has valuable displayed on him, a bunch of offenders who are very likely to be skilled recidivists, and a physical environment where they could easily get away without being stopped by either bystanders or police officers. It was noted that while the male victim had the intention to strike back, his wife stopped him because she was afraid to run into more trouble. This could as well be an effect caused by the hostility of the physical environment around them: the lack of pedestrian witnesses, inactive shops along the road, absence of justice personals in sight, and the general aura of the physical space which gives a sense of uncertainty about who lives behind these corners. An article on the news site The Local interviewed two entrepreneurs from Carrer de la Riera Baixa and Carrer d’En Roig respectively. Both these people complained that their businesses are harmed by those who commits acts of incivility because people would be afraid to visit their establishments. This information raises the point that the locals are also victims to the repeating offenders in the neighborhood. An insight can thus be obtained, which makes these people potential elements of collaboration in the effort of improving the level of public safety. More importantly, though, is that the security measures should never be introduced at the cost of their private assets.

An article on the news site The Local interviewed two entrepreneurs from Carrer de la Riera Baixa and Carrer d’En Roig respectively. Both these people complained that their businesses are harmed by those who commits acts of incivility because people would be afraid to visit their establishments. This information raises the point that the locals are also victims to the repeating offenders in the neighborhood. An insight can thus be obtained, which makes these people potential elements of collaboration in the effort of improving the level of public safety. More importantly, though, is that the security measures should never be introduced at the cost of their private assets.

A study conducted in 2021 by Magdalena Domínguez and Daniel Montolio investigated the effect of the community health policy in Barcelona (Barcelona Salut als Barris, BSaB) and its effect on crime rate between 2008 and 2014. It was indicated in this study that crime rate did see a general decrease in the neighborhoods where the policy has been implemented, in either long or short term. The policy’s main objective was to improve the access to health service in neighborhoods of needs, On the other hand, as it has been discussed earlier, the overall crime rate in Barcelona has been on a constant increase until the end of 2019. While the paper by Domínguez and Montolio stated that the community-oriented polices did have a positive impact on the reduction of criminal behaviors, the extent of its influence still needs be improved by follow-up measures that are able to exploit this benefit.

The importance of working with local entrepreneurs is further stated by the case of a reportedly stolen phone. Although a grain of salt should always be taken when obtaining information from online forums, what is being stated in this post can be assessed in conjunction with an important factor in our diagram of street crime: the reselling of stolen properties. It is highly likely that petty crime committers in El Raval would resell the stolen goods to a buyer in the neighborhood. Thus, considering integrating the local businesses in the security program may help to cut off another favorable condition for the offenders to act. On the other hand, their ring of activities could be more complicated and only deal away the lost property to outside buyers, in which case the collaboration with local shopkeepers can still be helpful as a preventive measure that helps to reduce the options for the offenders.

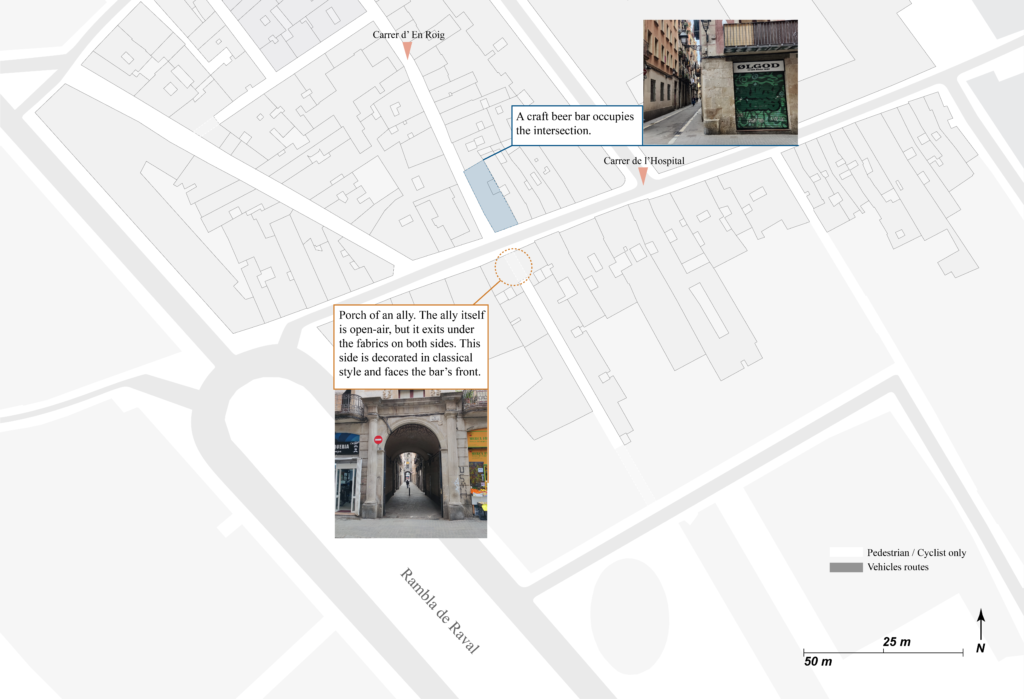

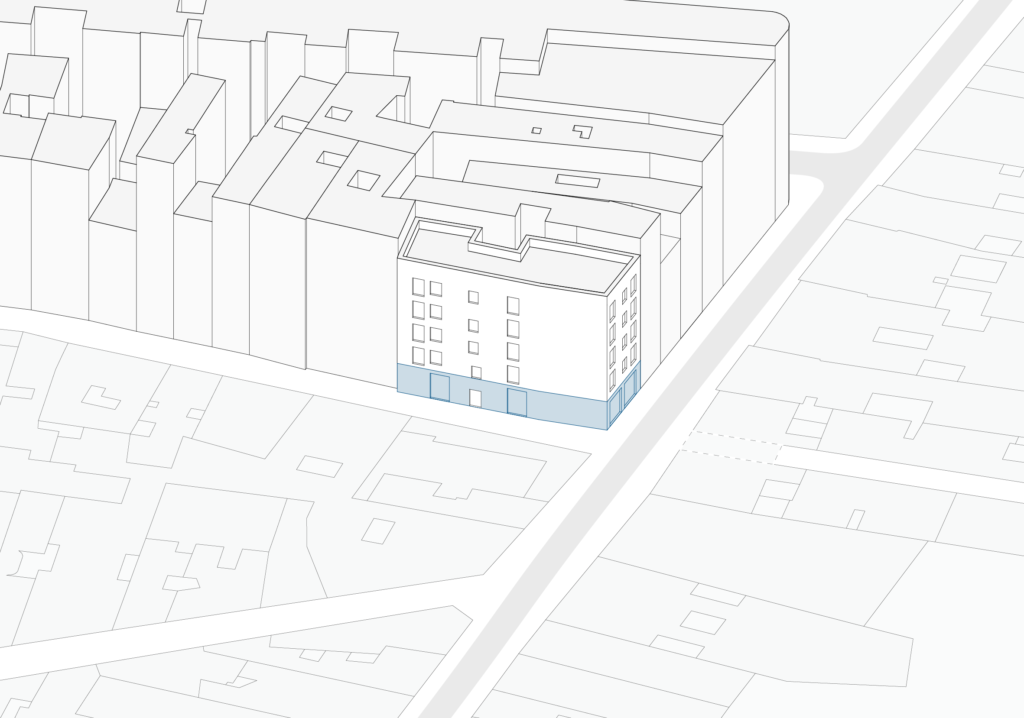

It is under these considerations that the project decided to choose a pub establishment located at the corner between Carrer de l’Hospital and Carrer d’En Roig as the first site of intervention.

As indicated on the plan, the location of this pub is right on a junction point that matches the description of a few critical factors that favors the final realization of a street crime. Not only that the physical space surrounding it represents the typical condition of El Raval’s narrow and complicated alleyways, the pub also operates only after evening. There are two other businesses facing it that opens in day time, yet both of them have way narrower openings and do not offer a decent angle to watch over, or be seen from the street. This condition generates not only a physical environment where witnesses cannot be guaranteed in the event of an offence, but also a perception of hostility with most of the roadside establishments being closed behind monolithic facades and heavily graffitied rolling shutters.

The plan of intervention is thus to be the mobilization of this pub’s space, from both its inside and the outside. Based on the theoretical groundworks discussed in the previous chapters, a set of strategies can be proposed to target the specific issues of this case study.

Strategies for Security

Followings are the strategies, drawn from how we understand the principles of public security so far:

- “Eyes on the streets”, the involvement of local businesses as active players in both the facilitating of community ties and the realization of a surveillance method based on reassurance.

- Surveillance based on nods of private businesses should also be integrated into a mutually supporting system, rapid response calls can be provided by police.

- Inclusiveness of activities. Local businesses that is equally enjoyed by the tourists and the locals, meaning that the service is not overpriced and the facade should offer an welcoming openness.

- Overlap of private business & public space, or the “defendable space”. As stated in the previous theory, the business can extend its sphere of influence on the streetscape to create a sense of territoriality, thus discouraging the unruly individuals from taking the advantages when the streets are vacant.

- The effect of D is best achieved by integrating the inner space of shops into the public space, this way both the effect of security and the revitalization of the cramped urban space can be achieved.

- Special attention on routes that are frequently used by tourists. Providing spatial hints of directions while not encouraging loitering.

- Lighting should be introduced to not only increased the perceived sense of security, but also to help improving the sense of direction.

A simple and cost-efficient strategy can thus be proposed to mobilize this establishment as an urban hinge point of community-based security.

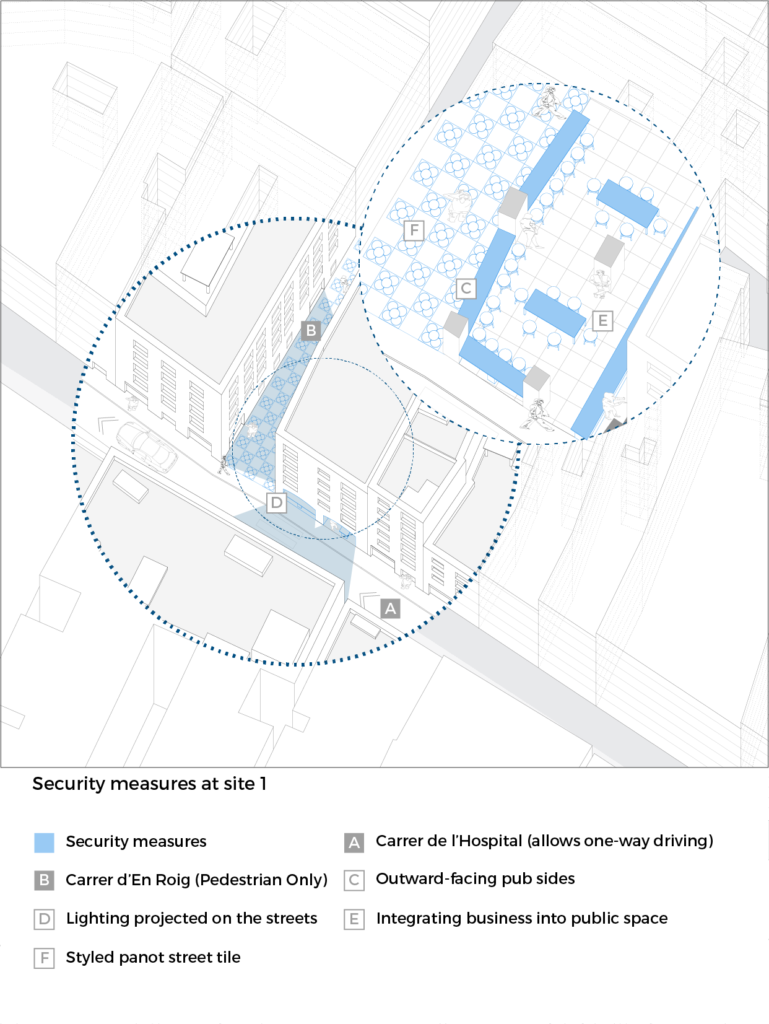

Proposed Intervention 1

Site: The Pub

The detailed plan of intervention at the pub site can thus be produced as shown.

The proposal aims to mobilize the limitation of El Raval’s physical space and turn it into its feature. The chosen site of intervention sets at the junction between an underdeveloped back alley (Carrer d’En Roig) and a busy access (Carrer de l’Hospital) that connects the hottest tourist attractions through the eastern side of El Raval (from La Boqueria on La Rambla to Rambla de Raval). Its position and orientation at a somewhat extruded corner ensure a strategic advantage, allowing it to play the proposed role of social hinge point more effectively.

The store sides, used to be wrapped by monolithic brick walls, are opened up after upgrading the load-bearing columns, thus transforming it into a free-standing ground floor. This allows the pub to operate directly over the sidewalks without hindering the movements on the narrow streets. More importantly, though, is that this would remove the visual hostility of solid, unwelcoming walls that might contributes to the generation of anxiousness towards the social atmosphere of the neighborhood. Especially given that the shop mainly operates after nightfall and often has a large group of, presumably local, teenagers loitering at its front door, having an open façade can help reduce the sense of uncertainty over what might be going on behind the walls. This way, the pub can become both a local public space of communal gathering and a welcoming urban feature for visitors passing by.

While the facilitation of community ties is supposed to take effect in the long term, the localized surveillance achieved by this intervention is expected to take effect in the short term. The business should be encouraged to extend its opening hours from after nightfall to afternoon, offering alternative services if opportunities allow. This way it will help to create a cluster of activities that mix up different populations at a joint where the flow of traffic used to disregard anything along the sidewalk, and remove the favorable environment for troublemakers to jump up at casual travelers off-guard. The integration of private business with public space also allows for an intricate way of implementing CCTV cameras: The store can have it installed to protect the interior space, but as the activities happening around the business can happen across its walls, there is a chance that the camera can record certain evidences.

The extra lighting provided by the business after dark is also important for both the elimination of hiding spots for offenders and reassuring visitors with their directions. This is further assisted by transforming the paving of Carrer d’En Roig to a series of stylized panot tiles along with improved rain sewage. This small feature can help reduce the impression of backwardness of the physical space, while also providing the visitors with a clear indicator of direction.

To conclude, this is a proposal that attempts to revitalize the street space at where things are difficult to maneuver. It helps to optimize the security status on the surrounding public space by increasing the number of eyes over what is going on and reducing the spatial negligence of the cramped neighborhood. This way, surveillance can be achieved on the bases of mutual respect of privacy.

Proposed Intervention 2

Site: The Pastry House

The second intervention is proposed for the pastry house that sets on the tip of a Y intersection, situated immediately next to where the first site is found. The proximity between the two sites allows them to be in sight of each other, and thus forming a new spatial connectivity.

As it is stated, the intervention proposal has a main aim of transforming the physical space of El Raval that were neglected in the previous regeneration program, in a way that allows it to facilitate street interactions between both the visitors and the residents, which renders the connectivity between each sites an important factor to consider. Other than the features which were already explained in the previous page, certain other security strategies are used in the proposal for this pastry shop.

Firstly, its triangular location is highly advantageous and allows the counter desk to operate directly with all three sides simultaneously. The degree of spatial transparency and uniformity is even more favorable than the previous site.

Secondly, the side alley in this case is a few meters wider than in the previous example, and some tailor businesses are already occupying its road space at a bit further down. This is already making this bit of the neighborhood a bit more welcoming for visitors, and the pastry shop can serve as a director and mediator that guides the spatial perception into a smoother transition.

Thirdly, it is proposed to place perpendicular store signs for every shop down this side alley. Although less frequented, Carrer de la Riera Baixa provides a verity of services along its narrow body (Fig.44.). Indicators of their existence that can be viewed from the more used passage will help to improve the perception of vividness in the neighborhood, while also offering a picturesque scenario for visitors who are not expecting to see a local business alley at this point of El Raval.

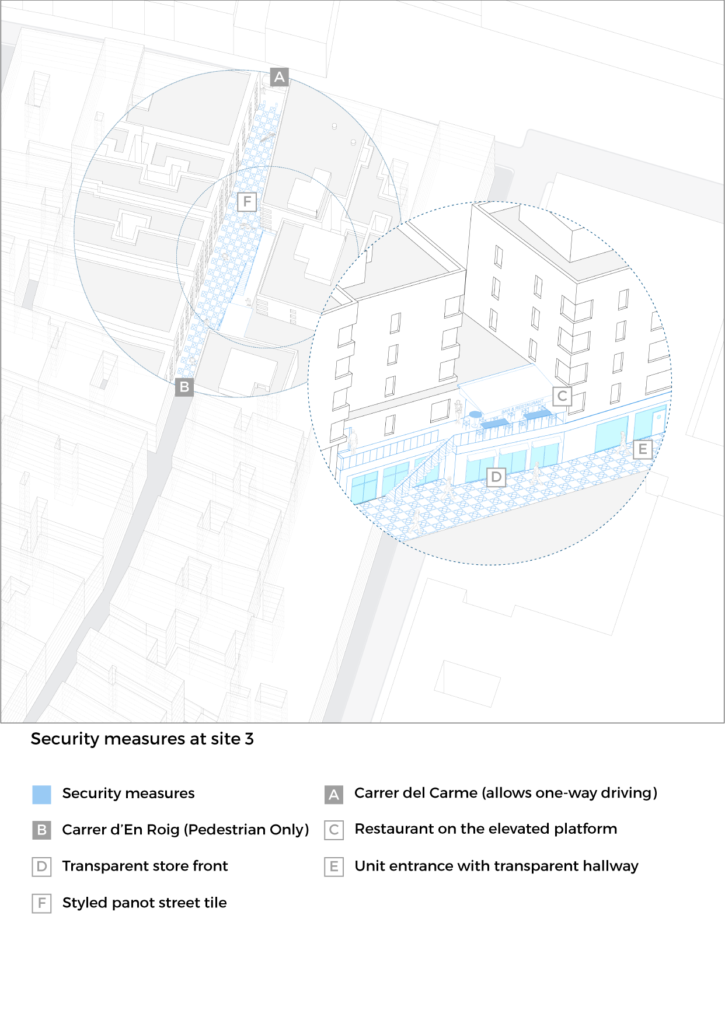

Proposed Intervention 3

Site: The Restaurant

The third site of intervention is a bar-restaurant, located at the northern end of the same alley as the first site. Again, the intervention takes the advantage of the existing physical space by placing a typical bar-restaurant over the extruded second floor of a residential unit.

The existing space at this junction point is far less than active, even with a supermarket and a cloth store on the ground floor. The apartment building that offers the potential site of intervention appears to be relatively recent. Its main superstructure setting behind a façade of louvers leaves a considerable area of the ground floor’s rooftop unused. The way that this building interacts with the streetscape also poses an obvious sign of regenerative intervention: it is tilted to make extra buffer zone between its own residential units and the opposing apartments, while having a semi-freestanding ground floor at its corner on the intersection.

The proposal thus assumed an additive approach, and utilized both of the apartment’s existing design features. Firstly, the tilted façade along the narrower alley allowed extra space for an exterior stairway to be attached on it. Secondly, the stairs can lead directly into a bar-restaurant of average size on the second floor, which can be created by reorganizing the interior space of the portion of the second floor that also has no superstructure above it.

Other than the proposed security effect of what has been stated previously, namely the facilitation of community interaction and the reactivation of the public space, this proposal also offers an alternative way of creating spatial variation in a neighborhood with very limited roadside space. As indicated by the theoretical part of the paper, symbols of active and decent use of the public space can always produce positive influence to the perception of security in a neighborhood.

In order to not interfere with the existing businesses at the same site, the proposal also considered a rework of their façades, making them more transparent and engaging with those who travel pass them. There is also an apartment entrance on the ground floor, which is sunken into the building. This creates a very cramped negative space along the roadside. The new proposal attempts to align it evenly with the sidewalk, so that the potential dead angles of vision can be eliminated, while visions from the hall of the apartment entrance is improved.

Impact Analysis & Conclusion

Honestly speaking, it is hard to say a word of certainty on what kind of effect these proposed interventions might have in either improving the actual security status of the street space or the reduction of the perceived level of insecurity among visitors; however, the principles used by the research and analysis which brought the intervention design into existence are certainly based on tested security theories.

Such is why the final proposal looked more like a community revitalization program than having anything specifically to do with crime prevention, which I believe is at least on a good direction. As stated previously, the danger of surveillance by public law enforcement agencies is that people do not have any idea of who is watching them and when. Utilizing those whose livelihoods are grounded on the street space can provide an interior surveillance system based on mutual acknowledgement and trust, because it would be the people who can look into each others’ eyes equally who are serving as the watchful eyes on the streets.

As of the crime actors, unfortunately their existence among peaceful folks can not be denied. It has often been said that people can easily be skeptical about the authority’s efforts of combating crimes, especially when a clearly identifiable population is involved, because it would always end up with the crime actors simply relocating their businesses to somewhere else. This makes it all the more important to not only consider the preventive measures against crime, but also to cut off the source of motivation for the actors. Motivating local businesses and encouraging a more active social environment is naturally going to help in that aspect. Afterall, nobody liked to be desperate.

For the design itself, the idea is that the thought model behind their visualization can be reproduced at every contested spot where activation can be achieved by utilizing certain spaces or collaborating with certain actors. In the case of El Raval, I do consider that if a large-scale act of revitalization can be realized based on the supports provided to local business owners, both the security status and the public image of the neighborhood can be significantly altered. There should not be any more tourist-targeted public facilities, though, since the density of tourist activity is right at a perceivable point. Should the flow of tourist population in El Raval goes far beyond the capacity of its alleyways like on the La Rambla, or even worse, like in Rome and Paris, then I am afraid that no remedies can ever cure the problem with crime rate, as there would be almost no room at all to maneuver other than inserting more active security personals into the crowd.

In a sense, it is fortunate that El Raval has not actually turned itself completely into the hands of tourists yet. Its apparent signs of deterioration are mostly due to the far simpler reason of economic underdevelopment among the population. On the other hand, the major population of the neighborhood are indeed made up of immigrants, and it might be difficult to find a good number of households that has lived here for more than one generation. Either way, the lack of communication between different demographic group is really problematic, because if Europeans, Asians, Africans, and Pakistanis all have their own circles of communities running in parallel in this crowded neighborhood, the level of miscommunication and the atmosphere of uncertainty can only ever become more severe.

At the end I would like to conclude this paper with some future expectations for the similar projects. In El Raval’s case, specifically, tourists’ security should naturally be ensured along their most frequented routes, and thus more sites of intervention should be selected along the passages leading to and leaving from Rambla de Raval and the MACBA museum. In fact, there should be an entire series of intervention sites that links up as a system along the route that connects these two attractions. As of the other European cities, the mode of thought is the only thing that this project can help to produce solutions based on their own specific conditions.