The Master’s in Advanced Ecological Buildings and Biocities (MAEBB) program at Valldaura Labs features the Collaborative Design Studio in its first term, also known as the Introduction to Self-Sufficiency. In recent years, the Collaborative Design Studio has engaged students in designing for and with diverse groups, working across various age groups, from school children to older generations and community residents. This course presents an exciting challenge: to collaboratively design and construct small-scale urban interventions.

Introduction

The global decline in physical activity among children is particularly alarming in dense urban areas, where limited outdoor spaces exacerbate the issue. Within these constraints, schoolyards are often reduced and, in many cases, confined to terraces as the only outdoor space available to schools.

The schoolyards are spaces where children spend a significant portion of their time during their formative years, time free of hard rules, time to socialize, a place to unwind. By definition, these spaces should provide children with the freedom to move, play, and express themselves without constraints.

However, they usually fail to meet the varied needs of students, creating significant disparities in how they are used by different genders and activity levels, leading to issues of spatial inequity, underutilization, and missed opportunities for healthy physical and social development. This problem doubles if the schoolyard is just a simple, small-in-area roof terrace.

To address these challenges, the participatory project “Activating the Courtyards of the Mare de Déu dels Àngels School as Climate Refuges and Inclusive Recreational and Educational Spaces” was launched. This initiative places health and freedom of expression at the forefront, recognizing the schoolyard as a critical space where children can enjoy unstructured time to explore, interact, and move freely.

Guided by an intersectional approach and informed by observations, interviews, and workshops with the school community, the project represents the first phase of a long-term effort to transform the terraces. By prioritizing inclusivity and well-being, this initiative seeks to create vibrant spaces that empower all students to actively engage, fostering both physical and emotional health while addressing gender-based disparities and ensuring equitable access for everyone.

Course Description and Objectives

- Less than 20% of children and adolescents meet the WHO’s recommended 60 minutes of daily physical activity – World Health Organization. (2020). “Global Status Report on Physical Activity 2020.”

- A UNICEF report reveals that modern children spend less time in face-to-face interactions than previous generations, leading to loneliness, poor social skills, and reduced emotional resilience. – UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti. (2017). “The impact of using digital technology on adolescent well-being.”

The Collaborative Design Studio course, part of the Master’s in Advanced Ecological Buildings and Biocities (MAEBB) at the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC), aimed to redefine architecture as a tool for social engagement and environmental stewardship. By engaging students in a hands-on, co-design process, the course sought to address the broader challenge of designing for inclusivity, sustainability, and social equity.

The first objective was to actively involve the school community – students and teachers – in the design process, ensuring that their needs and desires directly influenced the final outcome. Through observations, interviews, and workshops MAEBB students gathered crucial insights on how the terraces were currently used, identifying gaps and opportunities for improvement. This participatory process included a sex-based analysis, aiming to address the disparities in space usage that often exclude less active boys and girls.

The second objective was to equip MAEBB students with the skills and knowledge to transform theoretical design concepts into tangible outcomes. Students were tasked with conceptualizing, designing, and producing urban furniture, taking the project from initial sketches to physical installations. This collaborative effort fostered teamwork, allowing MAEBB students to experience the full design-to-production process while learning to create spaces that genuinely resonate with their users.

Finally, the project aimed to create a lasting impact on the school community by transforming the terraces into dynamic, inclusive spaces and fostering a sense of ownership and environmental stewardship among the students. This phase of the 3-year project sets the foundation for a long-term initiative that will continue to evolve in response to the needs and feedback of the school community

Analytical Process and Collaboration with the School Community

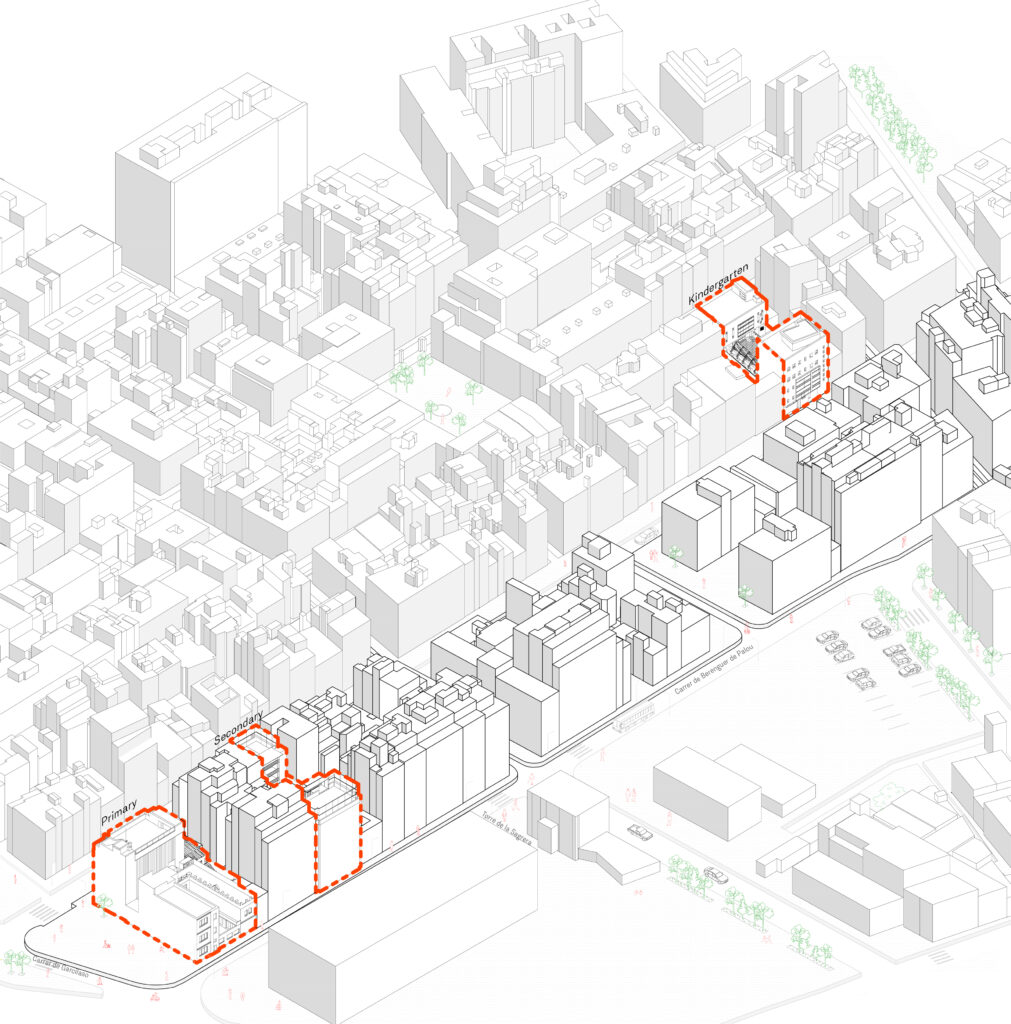

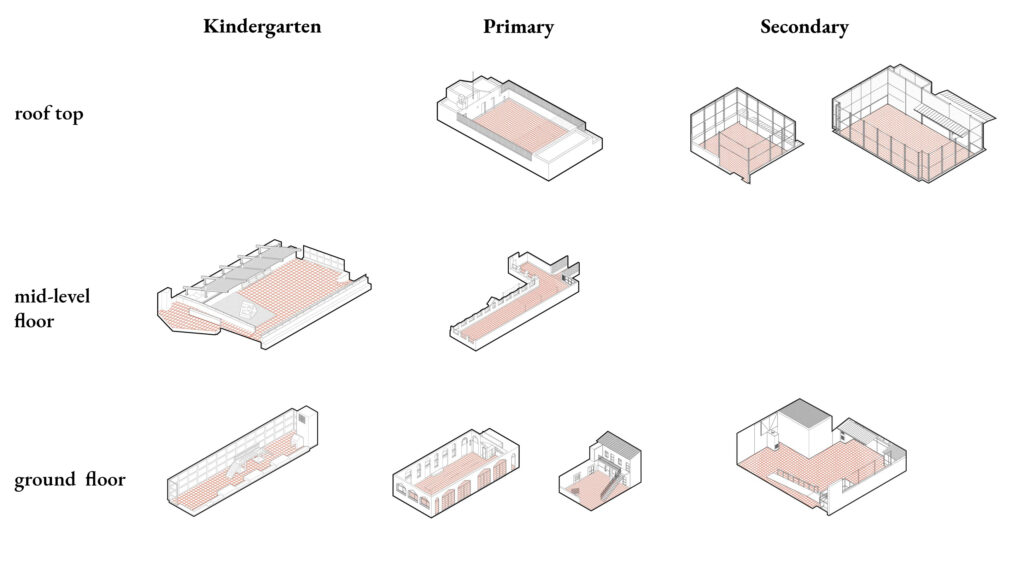

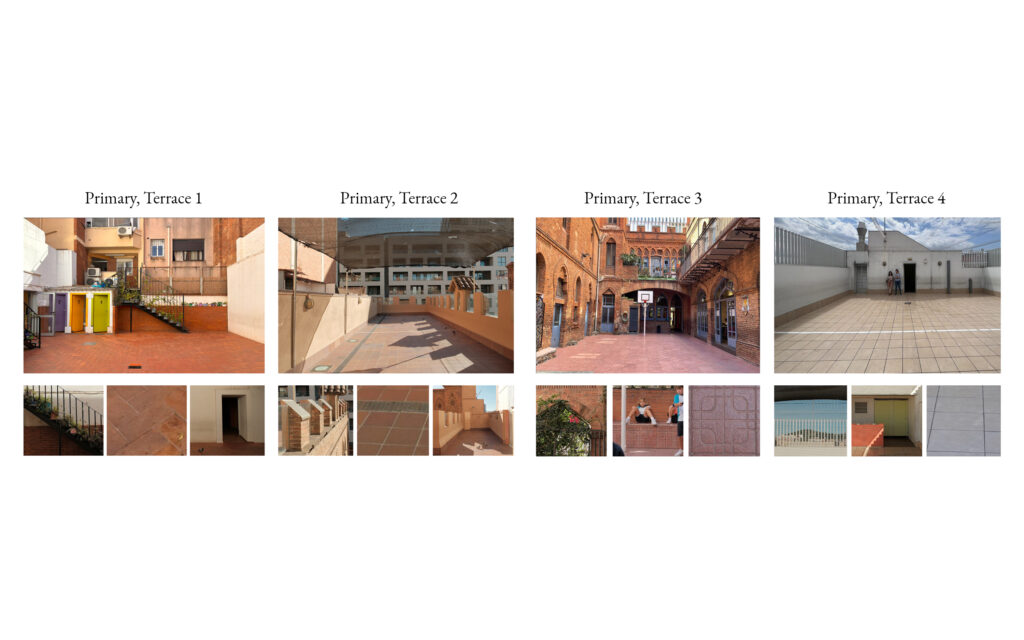

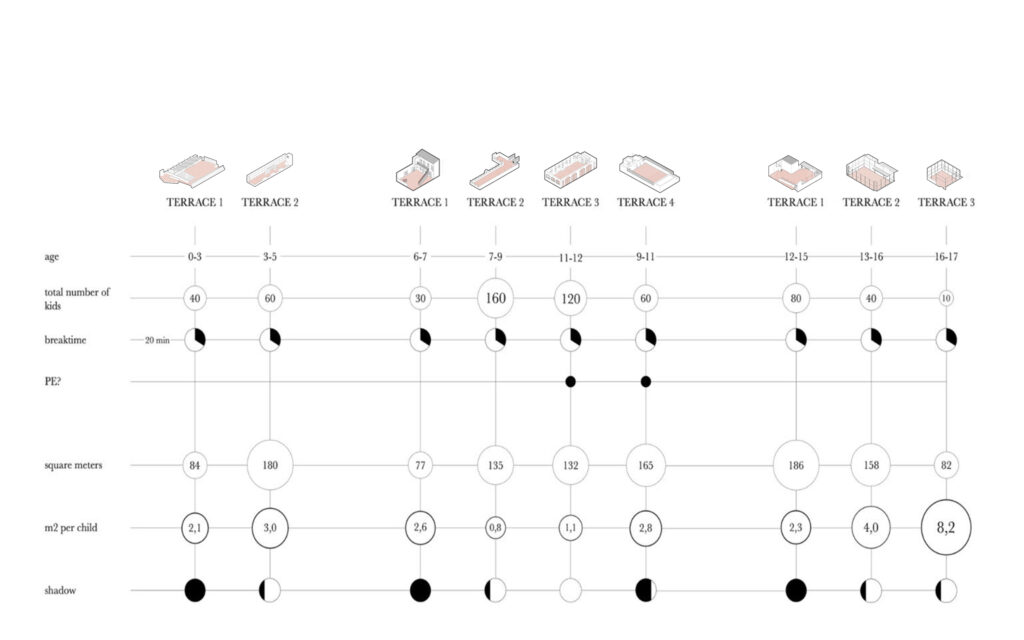

The design process began with an extensive analysis of the existing terraces at the Mare de Déu dels Àngels School, focusing on how the spaces were being used by different groups of students. The MAEBB students conducted an inventory, drew detailed plans, and documented each terrace’s specifics. This thorough process not only provided a solid foundation for the project but also created a sense of ownership for the school community, as the detailed maps and documentation allowed them to engage more deeply with their spaces.

The terraces are located on different levels, ranging from rooftop to intermediate terraces. Regardless of their size or position, they all have hard surfaces, such as concrete and tiles. They are completely bare, offering little more than the basic function of providing open air but no additional comfort or stimulating environment.

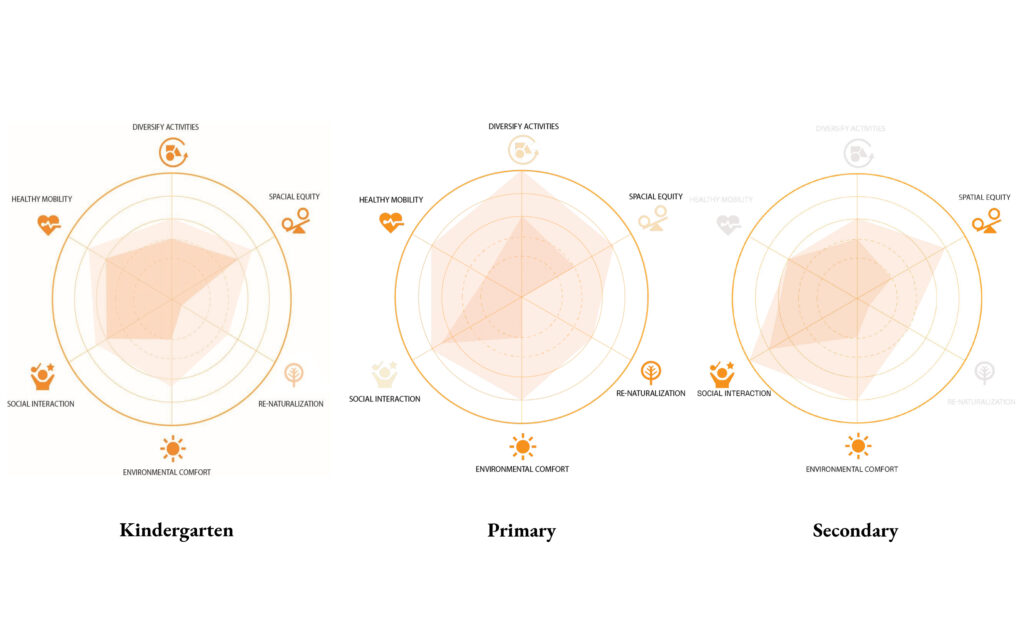

Building on this solid foundation, the design process moved into its first phase, where the MAEBB students conducted observations, interviews and workshops with school children, teachers. This allowed them to document the current state of the terraces and gather valuable insights. The analysis was age and sex-based, aiming to understand how different groups used the spaces and identify any patterns of spatial inequity.

A key insight from this phase was the significant disparity in how boys and girls, as well as more or less active children, used the terraces. Mostly boys, particularly those interested in football, tended to dominate the larger areas, while girls and less active boys were often relegated to the edges of the terraces or excluded from certain spaces altogether. This disparity became more pronounced with age.

Methodologies applied in the analysis stage:

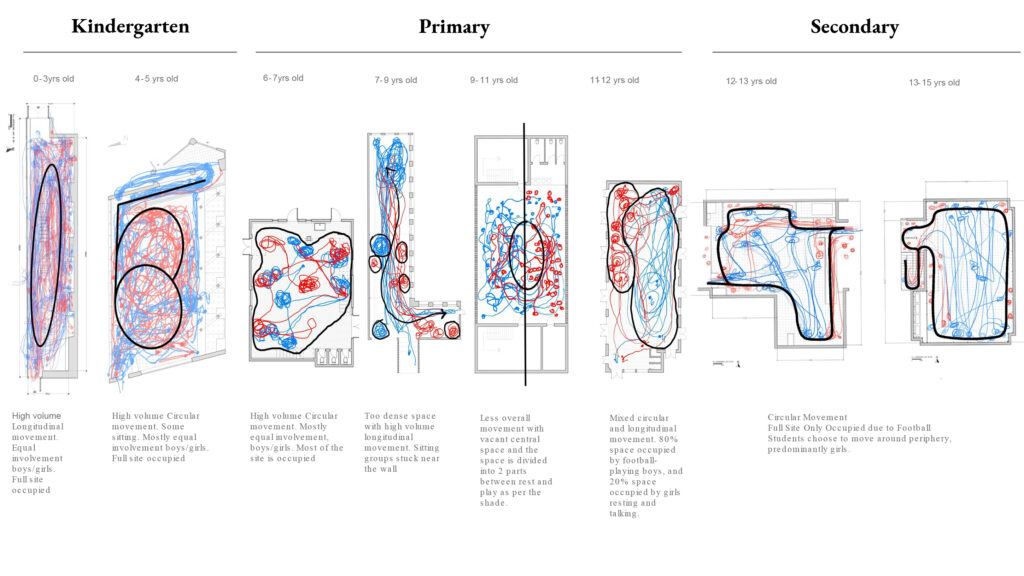

These movement maps illustrate how children’s physical activity in schoolyards changes with age, revealing a clear decline in overall movement and an increasing gender-based spatial divide. In kindergarten, boys and girls move freely and equally, with activity distributed across the entire yard. The youngest children engage in high-volume movement, with no distinct separation between sexes. The space is fully occupied, and the physical engagement is balanced.

As children enter primary school, movement begins to shift. While younger primary students still move actively, their use of space becomes denser, and small clusters of inactivity emerge. By the later years of primary school, the first signs of gendered spatial division appear. Boys continue engaging in active play, often occupying central areas, while girls begin to move towards the periphery, engaging in less dynamic activities. The central part of the schoolyard starts to empty out for those who are not part of the dominant physical games.

By secondary school, this division is fully established. The schoolyard becomes increasingly dominated by football, with boys occupying the central space for high-intensity movement, while girls mostly move along the periphery or remain stationary. The equal distribution of movement seen in early childhood disappears, replaced by a structured spatial hierarchy where active, high-energy play belongs to boys in the middle, and less active, socially oriented movement is pushed to the edges.

These patterns highlight a systemic issue in schoolyard design and social norms, where physical activity is gradually gendered over time. The early balance in movement fades as boys claim space for active play while girls become less mobile, often limited to the margins. This shift underscores the importance of designing inclusive outdoor spaces that encourage equal participation in physical activity beyond early childhood.

Other analyses were based on observations of children across different age groups, documenting their physical engagement with their own body.

In early childhood, the movement observed was a full-body experience. Kindergarten-aged children engaged in play that involves their entire bodies – they run, jump, crawl, climb, and tumble. Their limbs are fully engaged, and their play often includes physical interaction with their peers, such as holding hands, pushing, pulling, or lifting each other. Their movement is fluid, expressive, and uninhibited.

As children grow older, the observations conducted in primary school revealed that their movement patterns shift. By the age of 11, we see a noticeable reduction in full-body engagement. While some physical play remains, especially in sports or specific games, many interactions start to become less dynamic. Movement becomes more structured and less spontaneous.

By adolescence, physical engagement is significantly reduced. Teenagers in Secondary school tend to stand, lean, or sit in groups rather than move dynamically. Their social interactions often happen while being stationary, with minimal arm and leg movement. The once-expansive, active play of childhood is replaced with more reserved, subtle physical behaviors. This shift reflects not only changes in social dynamics but also how public space is used differently at each stage of development.

Based on the observations, the following conclusions were drawn: From ages 1 to 5, there was no significant difference in how children moved or used the space. During this time, boys and girls engaged equally, using all parts of their bodies and exploring various positions. However, starting from ages 6 to 7, a clear separation began to emerge. Girls and less active boys became progressively more sedentary, retreating to the edges or limiting their physical activity. By the end of ESO, they primarily stood or sat, while the larger, more central spaces continued to be dominated by physically active boys.

This analysis highlighted the need for a design that prioritizes inclusivity, ensuring all students have equal access to and engagement with the outdoor spaces, regardless of sex or activity level.

Design and construction

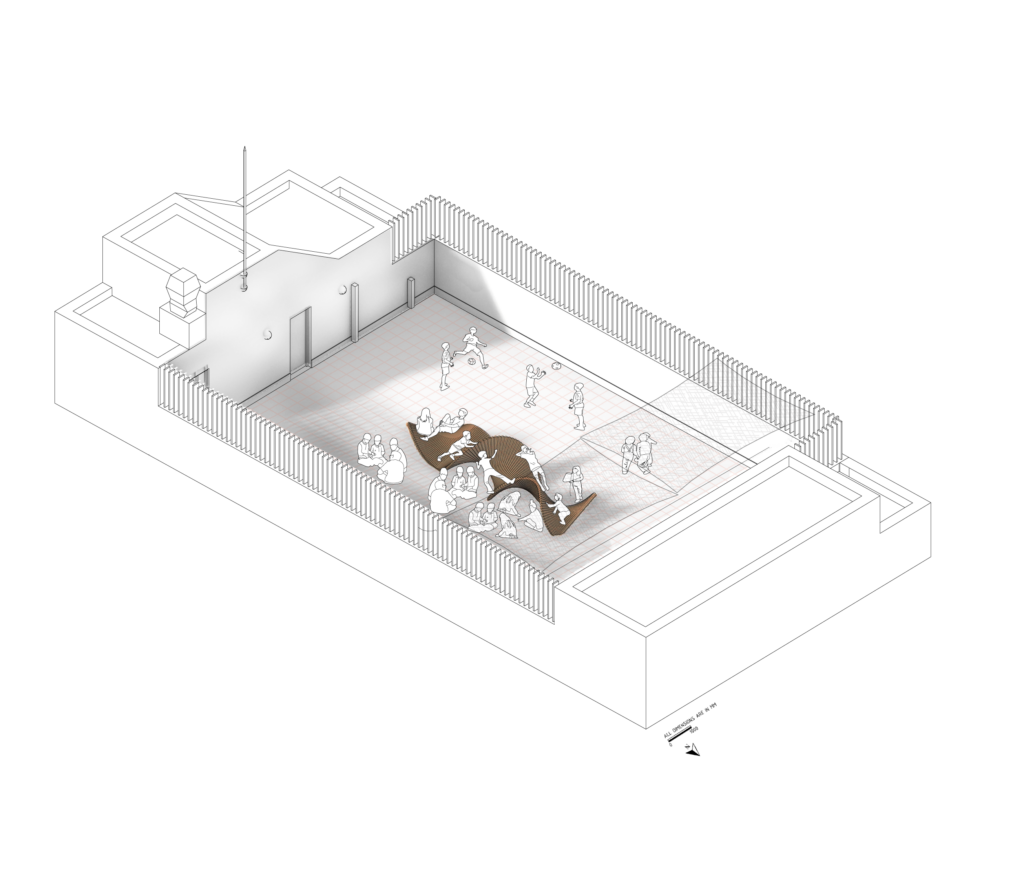

Building on these findings, the students developed a set of design criteria and chose three terraces in the most need. each one catering to the specific needs of different age groups: the kindergarten, primary, and secondary school terraces. The three terraces selected for the project were the ground-floor terrace of the secondary school, the rooftop terrace of the primary school, and the intermediate terrace of the kindergarten building.

As the design proposals took shape, the students refined their ideas through iterative feedback from the school community. This ensured that the final designs not only reflected the needs of the users but also fostered a sense of ownership among the school children and staff. The culmination of this collaborative effort was the final class, during which the designed urban furniture was installed on the terraces, transforming them into vibrant, inclusive spaces for education and play.

During the second month, the students worked collaboratively to design and produce urban furniture based on the insights gathered. This process included conceptualizing flexible, dynamic play elements that would foster movement, social interaction, and a connection to nature. The designs also addressed environmental sustainability, with materials chosen to reduce the ecological footprint and promote the long-term use of the terraces.

Kindergarten

The kindergarten terrace was a large, flat space with no vertical hierarchy, offering little more than an open area for running. The redesigned space supports the variety of activities and movements typical among young children, such as jumping, crawling, climbing, and sliding, while still accommodating their natural inclination for running play. This approach addresses the monotony of the terrace’s physical characteristics—primarily its flat surface—an issue common across all the terraces.

To overcome this, the design focused on manipulating the topography to create dynamic spaces that encourage diverse forms of movement and engagement, transforming the terrace into an environment that fosters creativity and physical exploration.

The design consists of three modular units, each measuring 1 meter by 3 meters, which can be arranged either side by side or stacked in front of each other. These modules create a continuous, angled, and wavy surface. Wood planks, placed at varying angles, are securely connected to the substructure below and painted in vibrant colors to spark curiosity and encourage active engagement from the children. The master students crafted all the wooden pieces, carefully sanding and routing the edges to ensure safety. Each module is lightweight enough for a few people to move, allowing the school administrators the flexibility to decide where to place the play elements.

Installation day

Primary

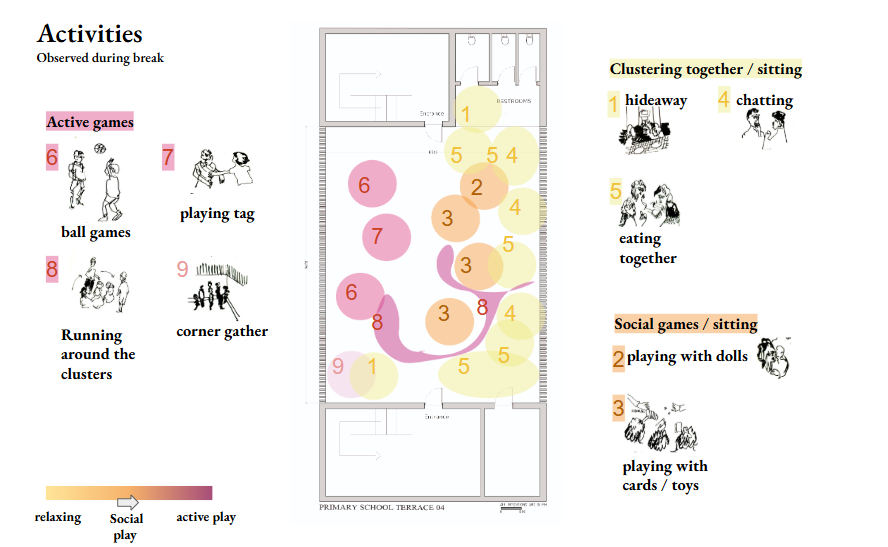

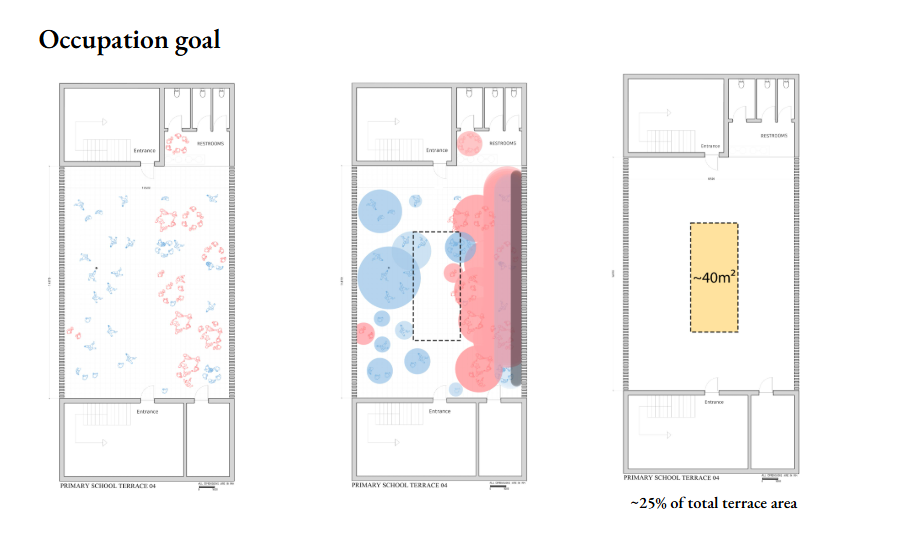

The redesign of the primary school terrace aimed to address clear spatial inequity and transform an underutilized space into a more inclusive and versatile environment for children. Analysis revealed a distinct division of the terrace into two areas: one side, shaded and accommodating 80% of the students, where children sat in groups on the floor, engaging in social interactions, and the other side, occupied by a small number of active children running and playing football. These two environments clashed, with little interaction and ongoing competition for space.

The area in the middle of the terrace was identified as a space of opportunity, sparking the design of an element intended to bridge the two halves. This intervention sought to invite physically inactive children to explore “the other side” while respecting and maintaining the unique qualities of both environments. By valuing both social and physical activities equally, the redesign encourages coexistence and inclusivity, fostering a space where all forms of engagement are celebrated.

Installation day

Inspired by tree branches, the twisting structure provides both shaded nooks and elevated paths. The lower sections create intimate spaces for gathering and quiet play, while the elevated parts encourage climbing, walking, and running, enriching their physical and social experiences. The flowing form integrates dynamic play areas with secluded spots for rest, fostering creativity and interaction with natural elements.

Built from thermally treated wood for durability and sustainability, the structure comprises 137 planks secured with over 530 bolts and 1,650 washers. Pre-assembled at IAAC’s Valldaura Labs, it showcases precision craftsmanship and thoughtful design, enhancing the terrace as a space for both active engagement and peaceful retreat.

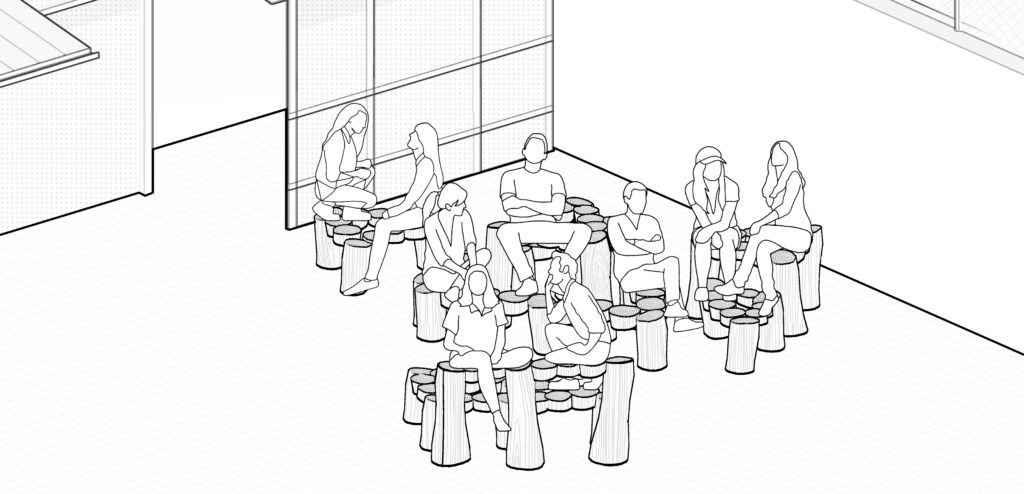

Secondary

The intervention on the secondary school terrace was a direct response to the significant demand from ESO and secondary school students for places to sit. While other needs and inequities were also present, the basic requirement of having spaces where teenagers could sit, talk, and socialize took precedence, as this activity is a daily occurrence for older students.

The design addresses several needs simultaneously. It provides seating options in various arrangements, allowing students to choose how they engage with the space. The inclusion of movable furniture enables them to reconfigure the layout, fostering a sense of agency and adaptability while encouraging interaction. Positioned adjacent to the cafeteria, the terrace seamlessly integrates with the area where students eat and drink, making it a multifunctional and dynamic social hub.

Pine tree trunks, harvested from Parc de Collserola by the students, were selected and cut to various heights. The bark of these trunks were removed and then connected using steel rods and nuts. The edges of the trunks were carefully sanded to ensure comfortable and safe seating.

Our mentors: Honorata Grzesikowska, Vicente Guallart, Esin Aydemir, Bruno Ganem