Every individual, regardless of age or economic status, can play a crucial role in shaping a sustainable future.

In Viladecans, a gamified co-design process is recommended to turn this vision into reality. Challenges of an aging population, energy poor buildings, and coastal climate change vulnerability may be aligned with public program priorities to adapt Viladecans’ infrastructure under a unique co-design process that leverages smart grid technologies and toolkits specific to vulnerabilities.

Approach

People in Focus

Vulnerable populations were understood as the most challenging for the city to support. With vulnerable people in focus, each module of the course was approached to locate solutions matching vulnerable populations’ needs aligned with public policy goals in places of distress.

Key Considerations

- Focus on the needs of vulnerable people

- Find climate-positive alternatives

- Find opportunities for resident involvement by way of power transfer and resource provision

Methodology

People and their Places

- Public goals, those of Viladecans, Spain and the European Union keyed into the needs of “vulnerable people”. People vulnerable to climate were found to be over 75 and under 5 years old. Those vulnerable to energy poverty are earn low-income and live in poorly energy-rated buildings.

- Analyses

- Demographic Shifts | Population projections revealed a rapid rise in those over 75 and with disabilities (gencat). Out of every 100 people, an additional 5 are estimated to be elderly and 9 may have a disability. Baseline projection scenarios were factored into the analysis. Estimates were derived from the age composition of Viladecans’ from 1987 through projections for 2040.

- Density by Age | To better understand where age vulnerable people live and spend time, the population density and frequented places of youth (under 5), elderly (over 75), and all (general) people were mapped by census region.

- Elderly and youth densities were inversely correlated.

- The population overall is dense in the Montserratina district and by the railroad.

- Frequented Places | Places categorized by population segment guided solution placement recommendations.

- Visits to Viladecans suggest outdoor eating, walking, and group socializing is common to residents. The daytime population is largely elderly.

- Daily journeys of residents by type were charted by first identifying points of origin, then destinations, and finally the transportation between spaces.

- The typical routes of residents by population segment drawn based on the attraction betweenness of resident journeys. The nodes driving the analysis were weighed by the density of the population segment.

- Social and Economic Vulnerability | To locate energy poor populations, energy intensive buildings were matched to economically vulnerable populations. Energy intensive buildings were identified as those with F and G ratings. Low-income populations earn less than 40 percent of the Area’s Median Income (AMI). The social vulnerability of residents is captured by the Census, and is similar to the Gini Index, increasing from 0 to 1 as income inequality rises.

- Economic Security | To understand opportunities for support, economically secure areas were identified as those with high earners and public infrastructure investments. High earners make more than 200% of the AMI and are the proposed source of new tax income. Public infrastructure can sustain new public investments in community technology such as solar panels.

Understanding the Policy Environment

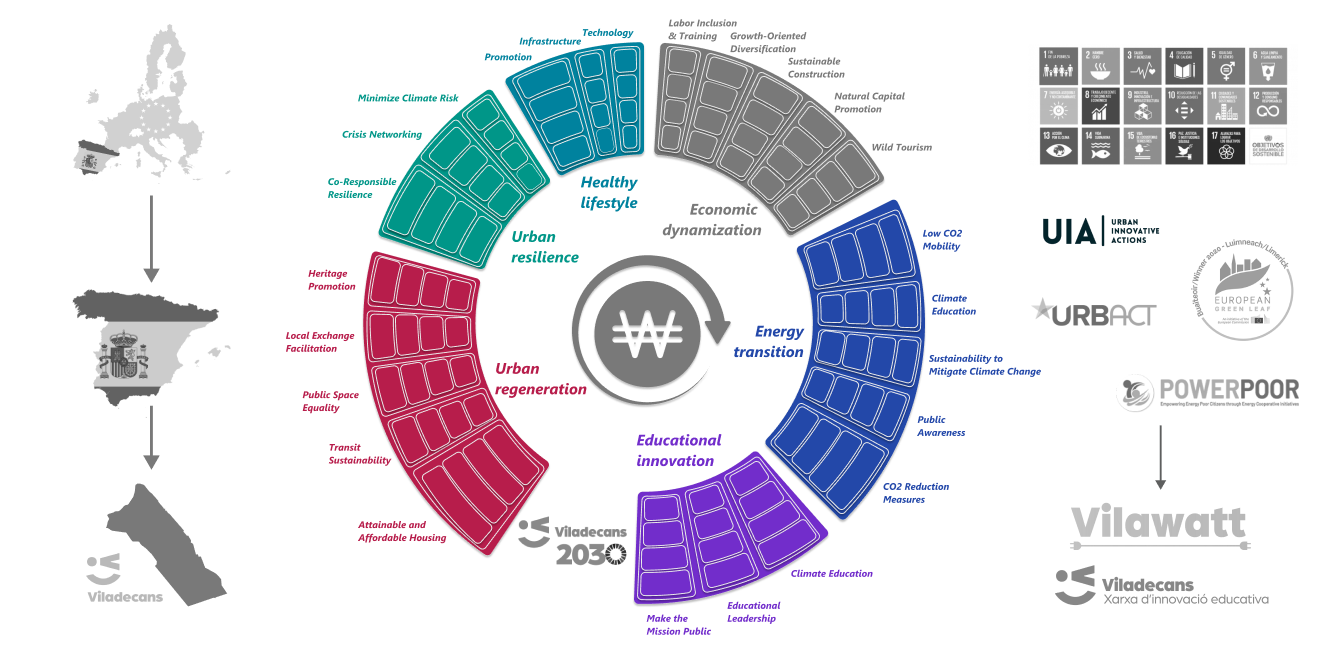

Prior to developing solutions an in-depth analysis was conducted of Viladecans’ 2030 strategic goals and likely available public policies and programs. Understanding that public projects typically receive European Union or National support, both EU and Spanish realized projects were analyzed for their alignment with Viladecans’ needs.

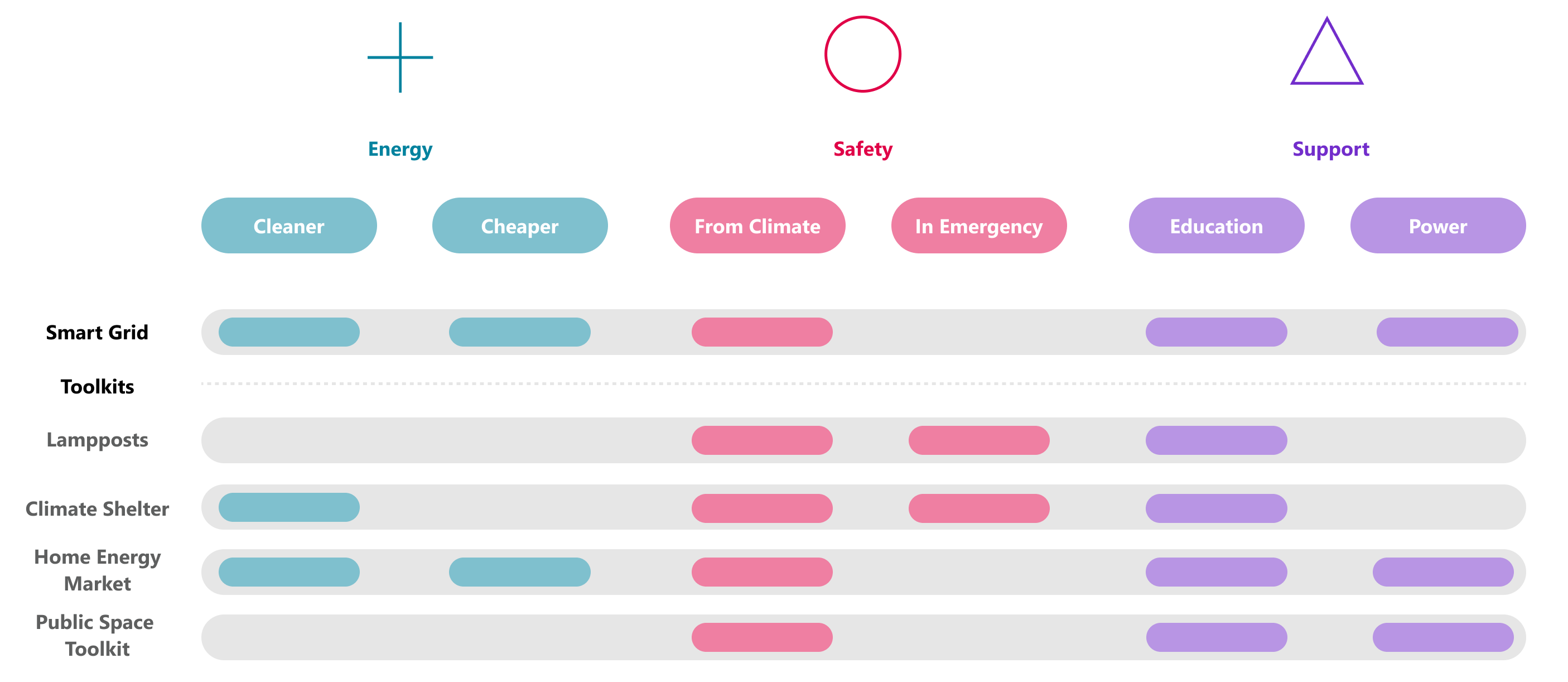

Aligning to the 2030 Strategy | The smart grid and co-design toolkit were elected as the underlying infrastructure for adaptive solutions. Each selected toolkit meets at least eight of Viladecans’ 25 goals. All 25 goals are met with the successful implementation of a smart grid and plug-in toolkits.

Recasting the Framework

- The goals of Viladecans and potential funding providers were recast to address the specific needs of Viladecans’ vulnerable residents.

- Each elected solution meets Viladecans’ key initiatives of safety from extreme climate and innovative education.

- Analysis of toolkit flexibilities guided recommendations of plug-ins supportive of vulnerable population needs.

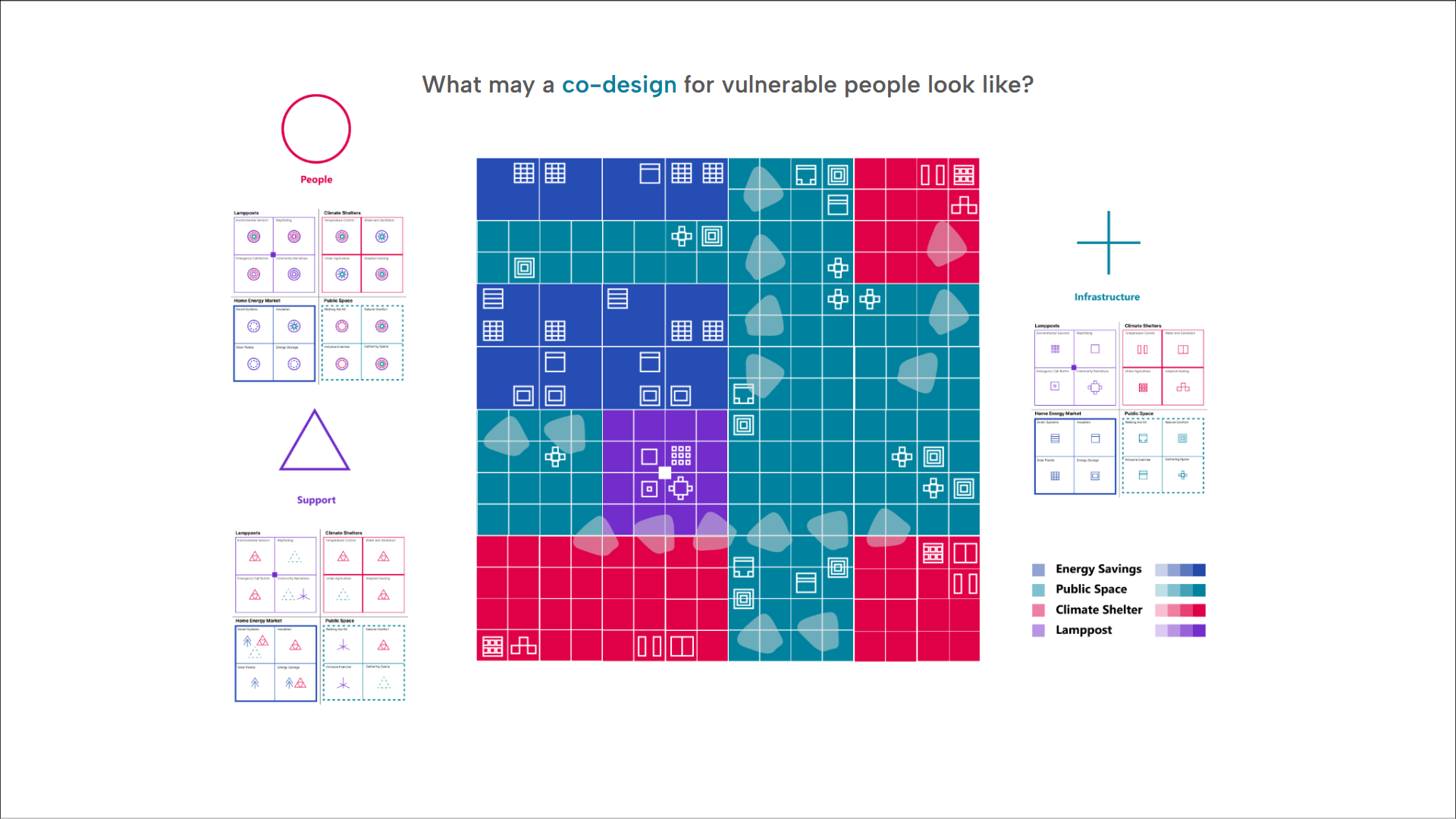

Decomplexifying for Co-Design

Smart grids are complex in their abilities operations but can be simplified during the co-design process by overlaying a grid and subsuming presence of vulnerable populations within relevant squares. Co-designers can then view the simplified needs of their landscape or address just the needs of their square.

Smart Grid | The smart grid is the infrastructural base for toolkit interventions. Smart grids optimize energy distribution and consumption and allow for the ongoing integration of renewable energy sources to meet community energy needs. Smart technologies collect data at the source of energy, along the grid, within storage, and on user meters to analyze usage patterns and redistribute energy. Residents are nudged to participate in energy exchange as unused energy from a home’s smart meter may be returned to the household in Vilawatts.

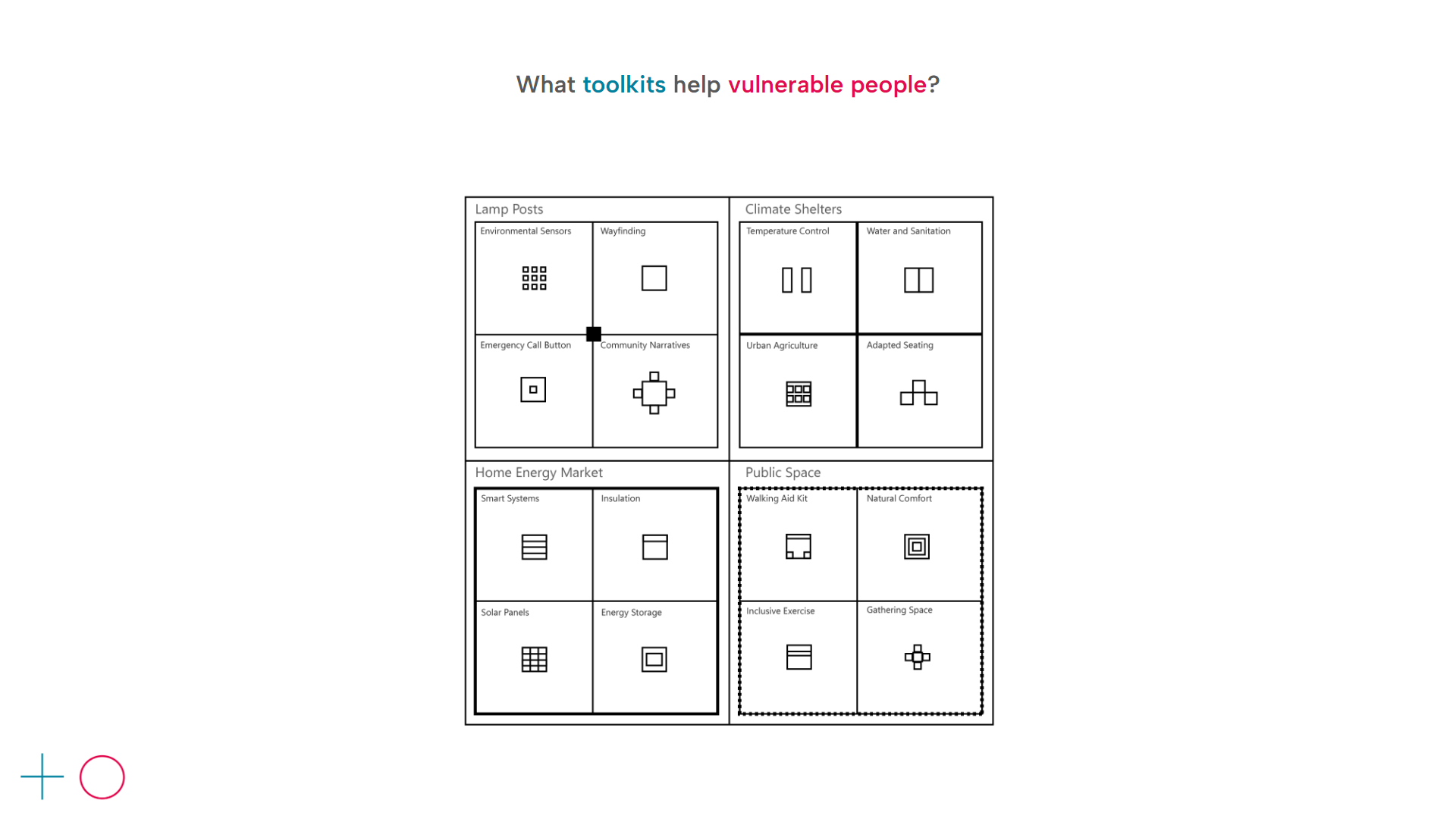

Focusing the tools in toolkits

- Selected toolkits address but expand beyond the needs of vulnerable people; they allow for citizen and private involvement and are adaptable to the changing needs of the population.

- Toolkits are kits of parts. Some parts specifically address the needs of vulnerable people. For each toolkit, four parts were identified to either support safety, involvement, or provision of energy.

Toolkits | Through toolkits focusing on empowerment, safety, and community engagement, residents are becoming architects of their sustainable environment. The typical nodes and paths of travel of elderly and youth residents guided the placement of climate shelters and lampposts and the recommended priorities for public space interventions. Given that toolkit parts change, the placement of each toolkit should be viewed as a unique opportunity to meet place-specific needs.

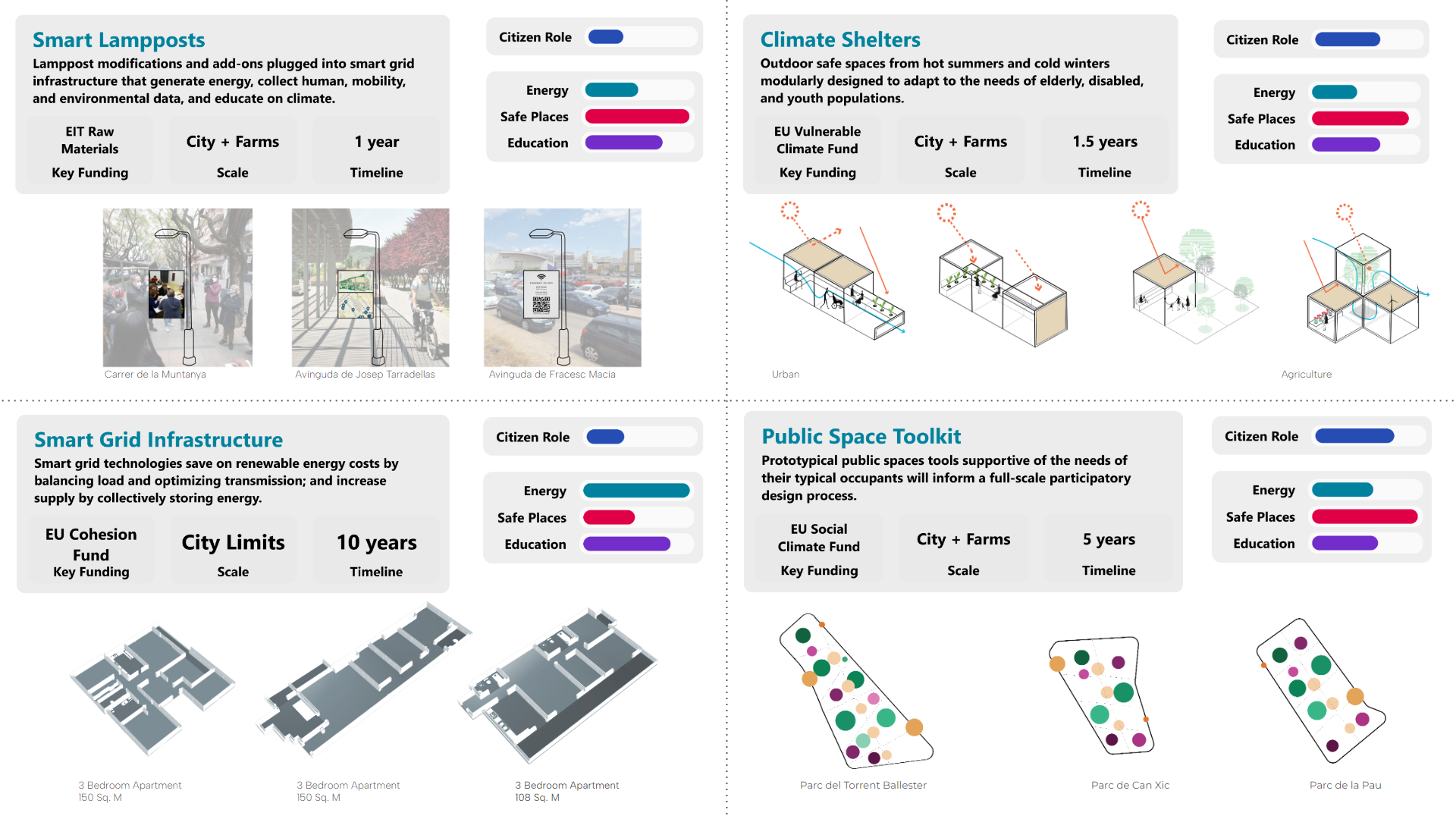

- Smart Lampposts | Lampposts are nodes of interaction between residents and their environment. Lamppost were placed to optimize their plug-in functionality. To ensure fruitful qualitative data collection, lamppost were placed at the intersections of routes frequented by elderly, youth, and the general population. Their initial placements intersect with climate shelter recommendations.

- Climate Shelters | .Climate shelters may be indoor or outdoor. Indoor climate shelters are placed in the lobbies of public facilities, mainly libraries and resident activity spaces. Outdoor climate shelters are placed at busstops near public spaces. Key busstops for intervention are not currently wheelchair accessible and are on the route frequented by the elderly population.

- Public Space Toolkit | Public spaces were segmented by vulnerable resident type based on the density of frequented places within walking distance, 500 meters. Spaces with high density of elderly, youth, and low-income populations were considered for a, later showcased, prototypical intervention.

- Home Energy Market | The home energy market supports households to collectively move towards carbon neutrality. Households with the greatest needs are energy poor, in E, F, and G rated buildings. Households easiest to support are in multifamily units due to the economies of scale of solution purchases.

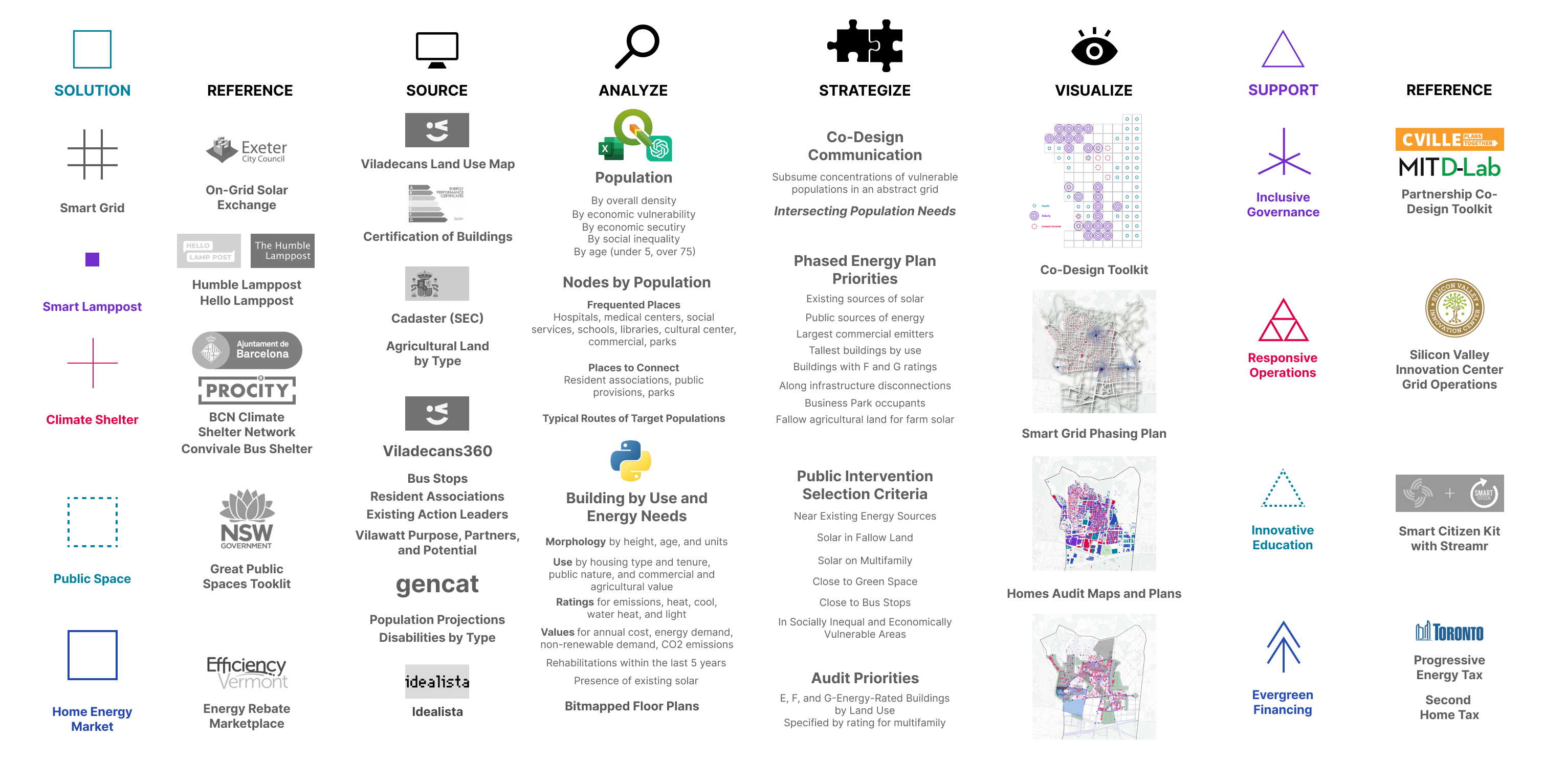

Locating Solutions

The recommended placement, co-design materials, and support infrastructure for each solution was developed iteratively under a process to:

- Reference | understand how overarching challenges are resolved through precedents,

- Source | source comparable open data for relevant context,

- Analyze | locate and analyze the conditions of the context,

- Strategize | fit challenges with the context of viable solutions,

- Visualize | develop tools to communicate strategies,

- Support | ensure tools are implemented with success.

Implementation Strategy

Phased Approach

A phased approach is recommended given the funding and socialization requirements to implement a smart grid. Central to this strategy is the active participation of the community, with partnerships and co-design efforts ensuring that solutions are both effective and embraced by those they aim to benefit.

Phasing the Smart Grid | The Smart Grid is a dynamic system that draws collective value from collective participation. Collective value is calculated as the quantity of clean energy that pulses through the grid. Viladecans has a head start on collective participation, with solar panels on the roofs of some private homes, public buildings, and industrial facilities.

- Phase 0 | Existing renewable energy nodes.

- Phase 1 | Networking existing sources through the extension of renewable energy transmitters and addition of key public nodes.

- Phase 2 | Incorporating private adopters, targeting multifamily with poor energy grades, and public hospital and school spaces.

- Phase 3 | Realizing multifamily, community solar projects and new public nodes.

- Phase 4 | Incorporation of private and household solar.

Key Takeaways

- The Vilawatt, VIladecans’ local currency, brought about as an Urban Innovative Action in 2018, was identified as a key opportunity to shift the focus of the economy to be equitable and climate positive. The value of the local currency, the Vilawatt, was challenged during COVID.

- Through the Vilawatt project, the city developed a Public-Private-Citizen partnership framework to share the responsibility to save energy.

- The value of energy savings is the quantity of Vilawatts and the currency value floats with the Euro.

- Viladecans has found meager but successful use cases for the Vilawatt but lacks a strategy to drive its continued use and intended integration into the citizen conscience.

- Vilawatts may be circulated with velocity by developing private markets for energy savings.

- The co-design strategy was derived from Viladecans’ Vilawatt framework and focus on innovation in education through involvement in local action.

- Co-design processes empowering community members to actively participate in the creation of solutions.

- The EU Social Cohesion Policy and Digital Education Plan identify co-design as a system worthy of financing.

- CVille Plans Together guided the relationships partners may build with one another and the cadence of partner interactions through the design process. The MIT Co-Design Framework identified the strategies for the engagement of diverse partners and the materials required for collective understanding.

- The smart grid solution was identified from Barcelona’s curve flattening strategy, Spain’s PowerPoor program, EU Cohesion Fund provisions. Specifically, the EU Cohesion Fund funds green and digital transitions of cities working to keep up with technological advance. Viladecans can capitalize on its proximity to Barcelona, a city keen on building smart and green technology, by submitting bids that align with the city’s technological advances. The smart grid system allows for the provision and ensures the optimal use of clean energy. The cost-savings of shared energy translate to lower energy costs for households and businesses, which can be collected as Vilawatts.

- Toolkits were found to be the adaptable solutions Viladecans needs to guide without imposing smart solutions.

- Smart Lampposts | Cross-Modal Data Collection and Interaction | Plug-ins available through The Hello Lamppost and Humble Lamppost, funded in many cities by the European Union and Neighborhood Programs, help cities better understand their environments, improve communication with citizens, and

- Climate Shelters | Modulating Safe Spaces | Modular panel systems, built from sustainable materials, wood and cork, can be tiled to shade and ventilate spaces at-risk of extreme temperatures. The EU Vulnerable Climate Fund and BCN Climate Shelter Network informed how these systems should create safer spaces.

- Public Space | Accessible, Natural Comfort |

- Home Energy Market | Stimulating Energy Savings | The Efficiency Vermont marketplace was a valuable case study to transform the Vilawatt into a tool that achieves empowerment goals.

Visualizing a Co-Design Process

Simplifying the City | Co-designers may leverage the abstract grid at a specific site by dividing the location into gridded parts, imagining each of those parts to be valuable for a specific toolkit, and finally placing toolkits where they are needed. Vulnerable population segments are represented as game pieces, distinguished by color and symbol, to help designers identify plug-ins specific to each site.

The prototypical intervention site was selected to showcase a design:

- for intersecting resident needs, where elderly, youth, and energy poor households are concentrated,

- with adjacent green space, within an 100m buffer,

- with busstops on-site,

- along the typical path taken by elderly residents,

- and in both socially inequal and economically vulnerable areas.

Just two locations in Viladecans meet all resident criteria and only one sits adjacent to green space. The selected location, a superblock next to the divisional railroad and along the southern border, contains roughly 230 homes and a park with barren groundcover.

Simplifying the Block | The site is abstracted into a grid for co-designers to understand site conditions: land use, proximity to amenities, and energy needs. The Spanish Cadaster and Certification of Buildings allow for identification of households by age and energy poor status by household. The grid again decomplexifies and anonymizes co-design materials.

Impact and Direction

Path Forward

The immediate benefits of the project are tangible, with reduced energy costs, enhanced public spaces, and a strengthened sense of community resilience. Looking ahead, Viladecans serves as a blueprint for sustainable urban development, offering valuable lessons on the integration of technology and community collaboration in addressing urban challenges.

Keys to Success

- Governance | Patience and on-going commitment | Implementation through the recommended co-design framework will take time and require assistance from Vilawatt partners.

- The public-private-citizen-assistance (PPCP) governance structure leverages the existing workstream structure for inclusion. Workstreams, headed by the lead of the project and with a member of each governance member on the board, will form the basis for toolkit implementation.

- Public partners may lead smart grid and public space toolkit implementation. These solutions are visible, costly, and procedurally complex.

- Citizens may lead the implementation of lampposts. Plug-ins from the Hello Lamppost and Humble Lamppost toolkits are highly customizable, are specific to vulnerabilities, and showcase the histories of residents. Coordination and procurement should be carried out with assistance partners. Educational materials may be developed with citizens to increase lamppost engagement.

- Private partners may help to realize climate shelters. Modular climate shelters are composed of sustainable construction materials, have space for local advertising, and can vend local products.

- Assistance partners may develop and support the implementation of a home energy market. The complex procurement, ongoing management, and technical education material development for a marketplace for energy saving technologies requires the expertise of energy infrastructure partners.

- Financing | Evergreen in nature and targeted in practice | Viladecans can independently and externally fund smart grid and toolkit solutions through identified programs.

- Local budgetary opportunities | Additional operating capital may be accessed by primarily increasing the tax rate, last shifted in 2006, by placing a tax on 200% or greater AMI households for their energy consumption, and cracking down on second home taxation, which fell ~60% during COVID.

- Targeted funding programs | Programs supportive of each policy intervention were identified as starting points for pilot program funding.

- A smart grid would require multiple levels of low-cost financing, accessible through Spain’s National Energy Efficiency Fund or PowerPoor program and the EU’s Cohesion Fund.

- The EIT Raw Materials program has funded smart lampposts.

- Climate shelters may access the EU’s Vulnerable Climate Fund.

- Public spaces intervention costs are highly variable. Light touch interventions can be funded through programs under the ‘Fit for 55’ strategy while larger projects may access the EU’s Social Climate Fund.

- Education | Innovative and specific to residents | Education can become innovative by varying the use cases for and methods of citizen involvement.

- Responsibility | Citizens may take an active role in shepherding the implementation of smart lampposts. This would require outreach to resident associations typically championed by a single or a few individuals.

- Relaying Information | Materials developed with assistance partners may contain information on the strategic placement of new lampposts and addition of plug-ins to existing lampposts. The simplified smart grid may prove helpful for initial site selection.

- Weighing Tradeoffs | The cost, timing, and abilities of each solution should be communicated to facilitate debate among residents.

- A Time Capsule | The Hello Lamppost, specifically, allows for community members to relay and record their experience in places. This recorded history can serve as a time capsule for future generations to understand the history of their place.

- Operations | Responsive to changing realities | The adaptability and modularity of the smart grid and toolkit solutions ensure they can respond to changing climate realities and demands for energy.

- Embracing New Technology | An annual review of new technologies specific to each toolkit should be conducted to stay current on the best practices and plug-ins for toolkits. For example, the home energy market should update their product list to match cost constraints with available technologies.

- Acting on Newly Available Data

- Environmental and qualitative data collected by the lampposts, energy supply and demand data collected by smart grid meters, and product demand data captured by the home energy market should be used to calibrate toolkit offerings to resident preferences.

- New census, cadastral, and building certification data will refine understanding of the age and energy poverty compositions. Materials and strategies should be updated to reflect these changes.

Sources

- Adjuntament de Viladecans.

- Viladecans 360.

- VIGEM.

- VIURBANA.

- Circle-Gespromat.

- Catalan Institute of Energy.

- European Investment Bank.

- Ciclica.

- Government of Spain Cadastral Property.

- Catalonia Open Data.

- CVill Plans Together.

- MIT Co-Design.

- Smart Citizen Kit.

- City of Toronto.

- Efficiency Vermont.

- New South Wales Government.

- EU Social Cohesion Fund.

- EU Horizon Programme.

- The Noun Project