Ndama, the fastest-growing informal settlement in Rundu, Namibia, faces critical challenges in water accessibility shaped by gender, age, income, and spatial isolation. With women disproportionately responsible for water collection under unsafe and inequitable conditions, our study combines interviews and spatial data to map intersectional vulnerabilities. We developed an interactive tool that simulates real-world constraints—heat, crime, and distance—to inform equitable planning. Complemented by an immersive experience of daily water-fetching struggles, this project supports inclusive decision-making and spatial justice through participatory, data-driven methods tailored to Ndama’s evolving needs.

Context

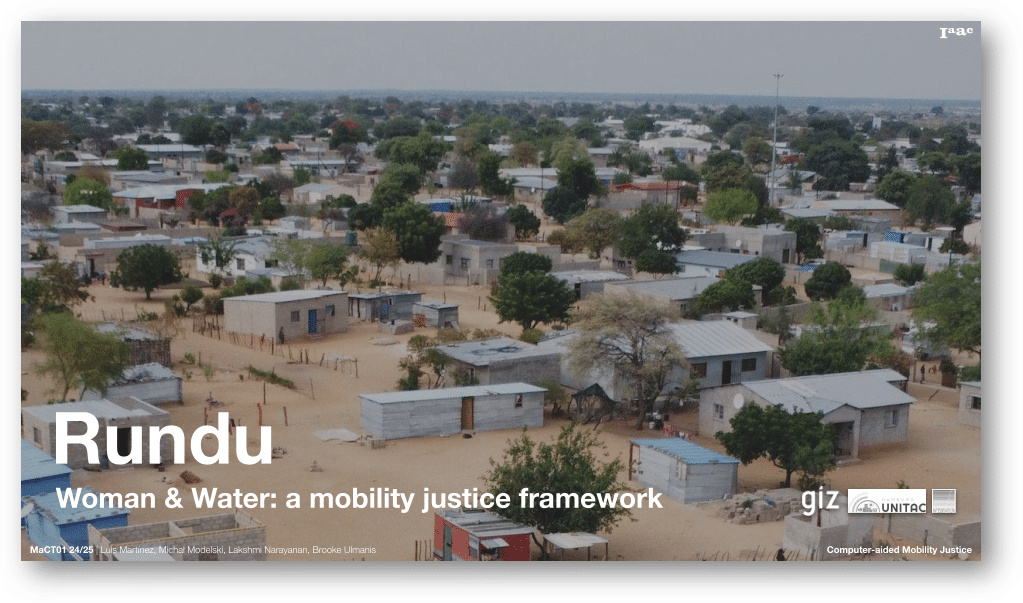

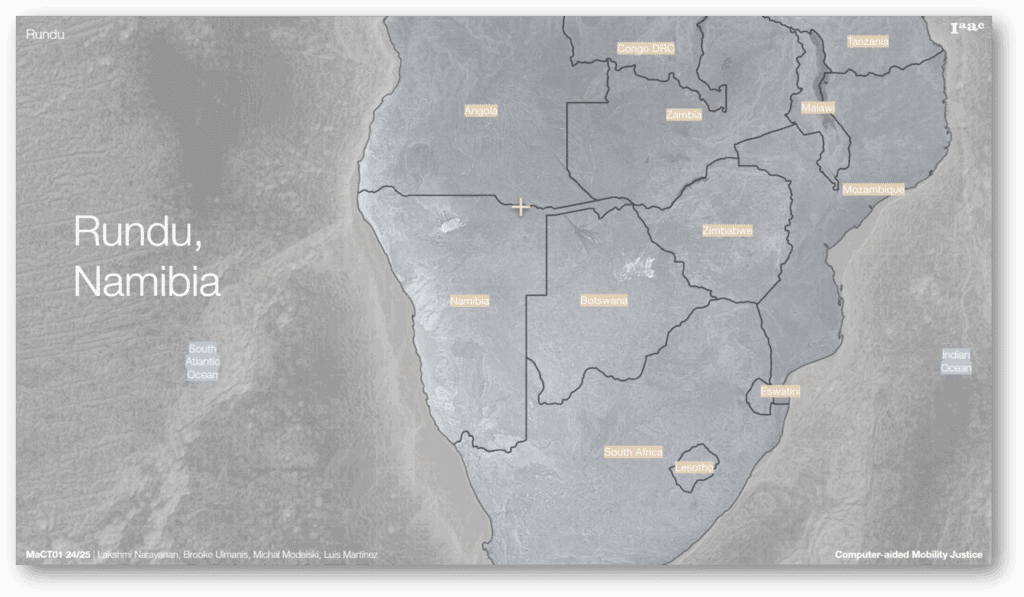

This study is situated in Rundu, a rapidly growing urban center located at Namibia’s northeastern border with Angola. Rundu serves as the capital of the Kavango East region, although it lies in close proximity to the border of Kavango West. The city’s dynamic position as a border town has significant implications for migration, economic activity, and urban development.

Rundu is currently experiencing substantial demographic and spatial expansion. The population is growing at a rate of 5.4% annually, while the built-up area expands by only 4%, suggesting that infrastructure and housing development are struggling to keep pace. According to the 2023 census, Rundu’s population has surged to over 118,000—an increase of 82,000 since the 2001 census, which recorded only 36,000 inhabitants. Women comprise approximately 54% of the current population.

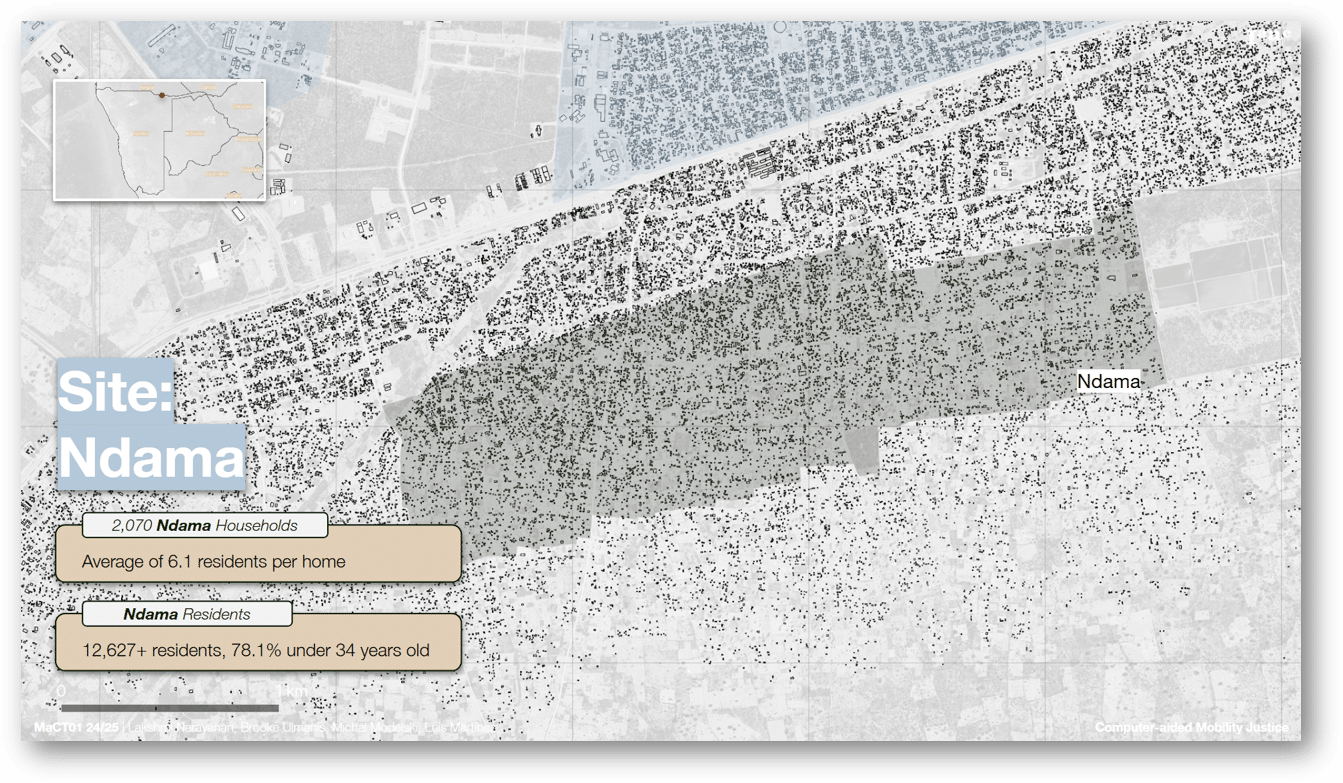

Ndama, an informal settlement at the south of Rundu, has seen rapid growth, now home to more than 12,000 residents. With an average household size of 6.1, and over 78% of the population under the age of 34, the settlement exhibits a distinctly youthful demographic profile. Given the region’s lower life expectancy, individuals in this age group are often considered middle-aged in local terms.

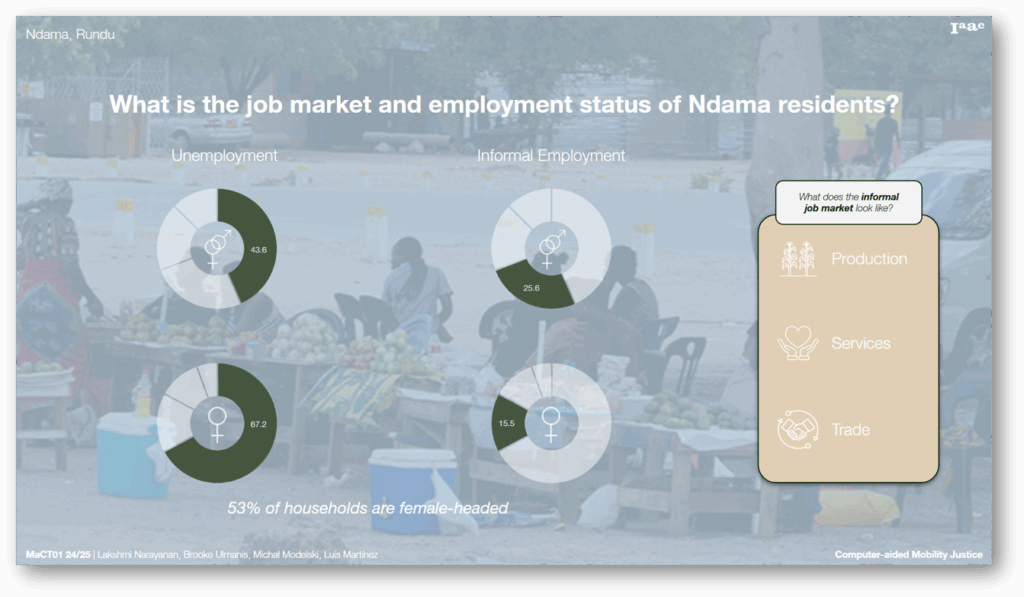

Employment & Income

The socio-economic challenges facing Ndama are particularly acute for women. The overall unemployment rate stands at 43.6%, but this figure rises sharply to 67.2% among women. This is especially concerning when considering that 53% of households are female-headed, placing the burden of economic provision squarely on women’s shoulders. Informal employment accounts for 25.6% of the labor market, with 15.5% of these positions occupied by women. These jobs—typically in informal production, services, and trade—often involve long hours, unstable working conditions, and irregular pay.

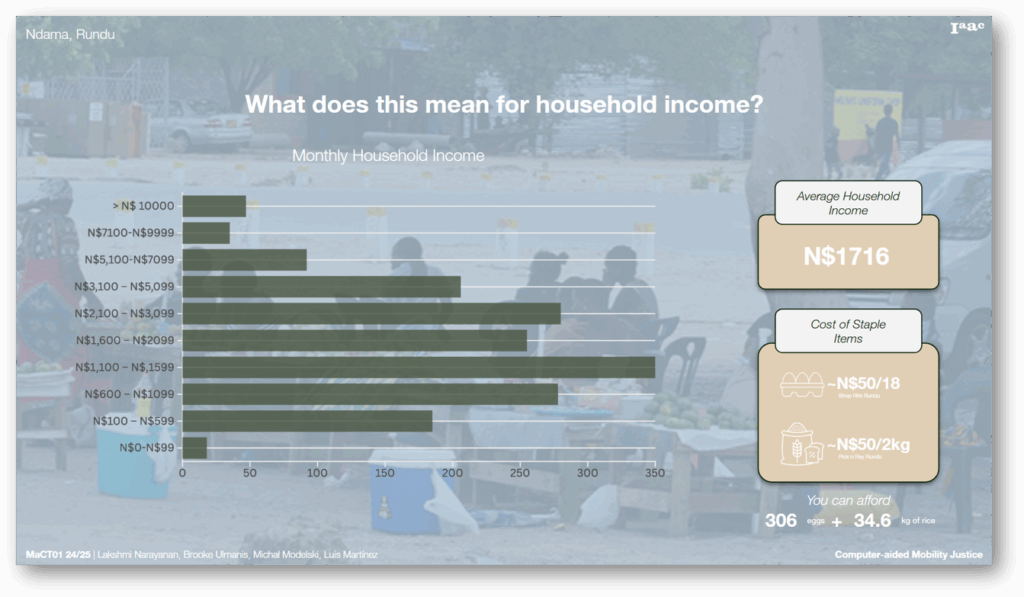

In terms of income, the average monthly household income in Ndama is approximately 1,716 Namibian dollars. To contextualize this, it could purchase about 306 eggs or 35 kilograms of rice. Average household savings are only 441 dollars per month—a figure that underscores the settlement’s financial vulnerability. This limited economic buffer leaves households particularly exposed to food shortages and emergencies, directly affecting their access to essential services such as water and transportation.

As said by Queen Kuveza, member of the Integration Consultant Team in Rundu:

Water & Transportation

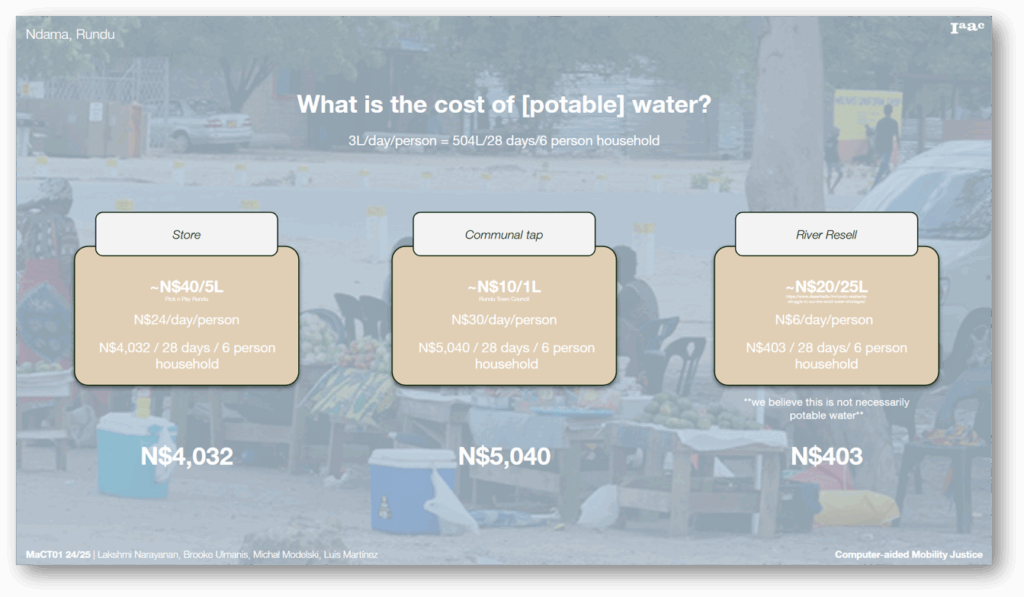

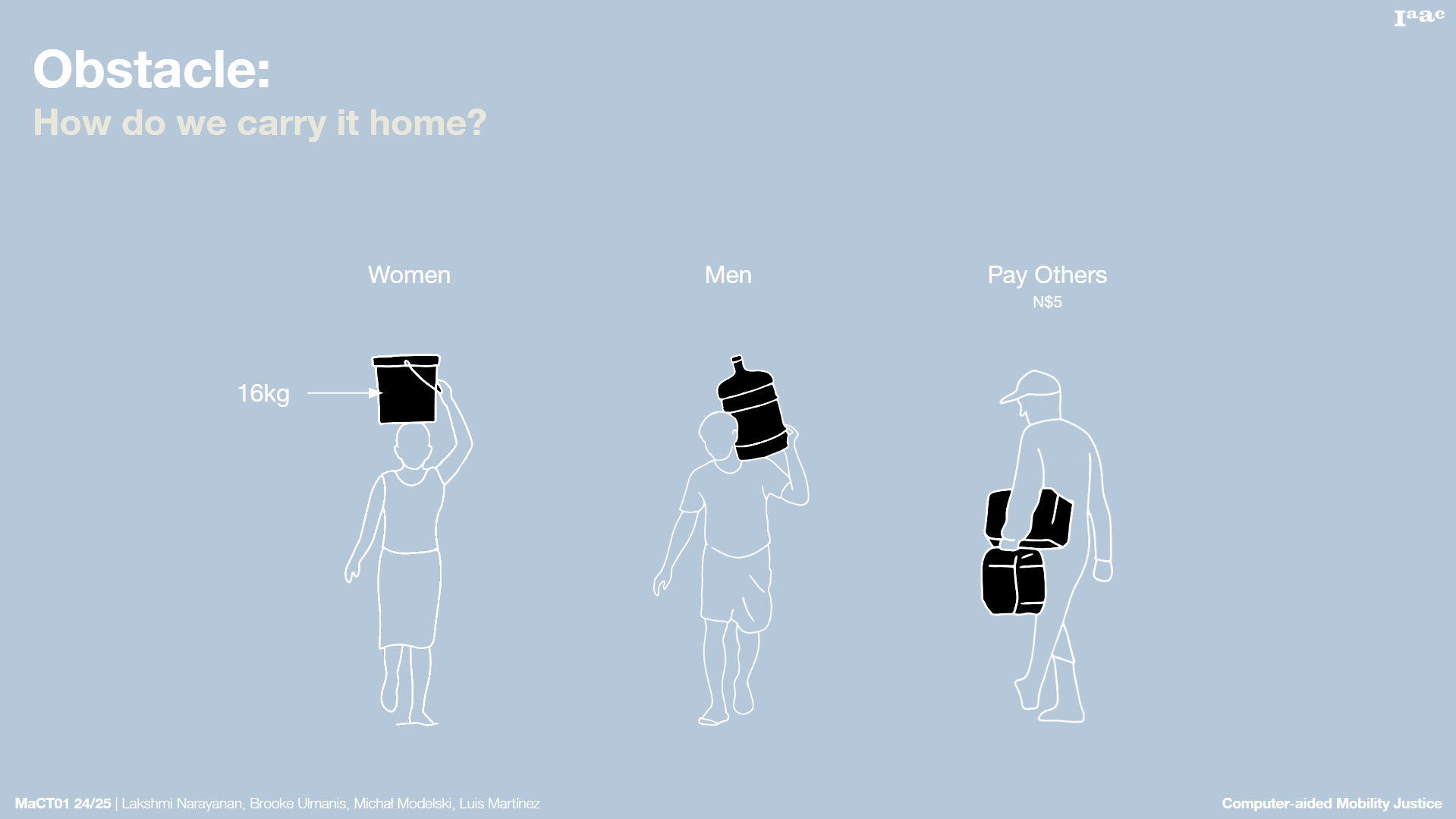

Access to water in Ndama is costly and complicated. Households typically rely on three sources: store-bought bottled water, prepaid public taps, or resold water (either river or municipal). The latter is the most affordable option, yet still financially burdensome, particularly since these costs are for drinking water alone. The responsibility of collecting water falls disproportionately on women and children, who must walk long distances, often under harsh conditions.

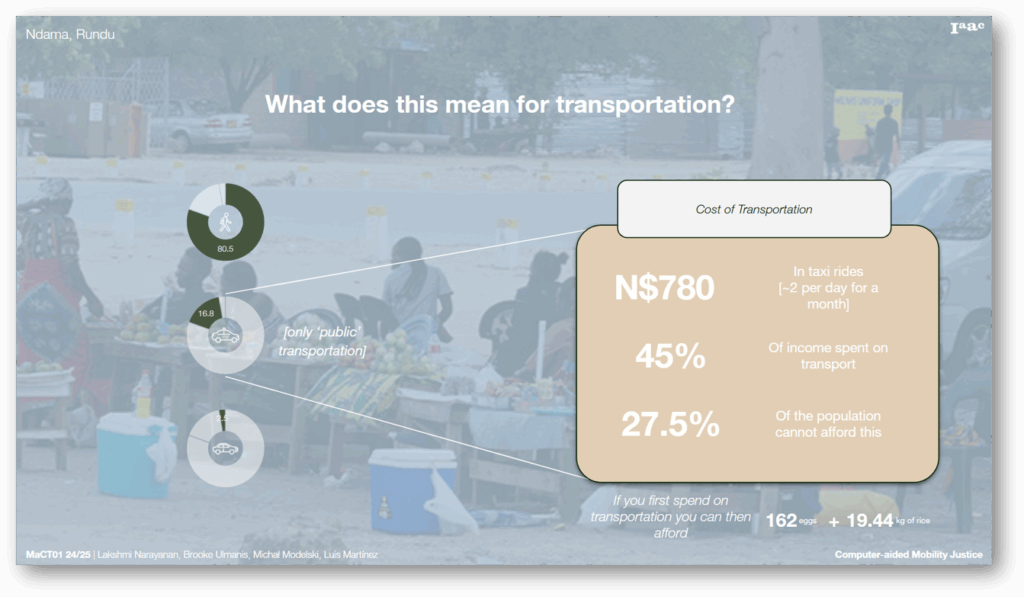

Transportation is similarly constrained. With no public transit system in place, residents rely on three primary modes of transport: walking, taxis, and private vehicles. Most people walk due to economic necessity. Using taxis for daily commutes can cost as much as 780 Namibian dollars per month—equivalent to 45% of the average household income and exceeding the total income of 27.5% of the population. Consequently, high transport costs reduce available funds for basic necessities, such as food, and reinforce the cycle of poverty.

Obstacles

The Water Collection Experience

The central issue under investigation is access to water, identified as a critical concern through preliminary contextual research. To move beyond quantitative data, a set of semi-structured interview questions was designed to explore this topic in depth. The objective was to gain insight into the daily lived experiences of community members regarding water collection. These interviews revealed the tangible and persistent effects of water scarcity on daily life.

A total of seven interviews were conducted, with 22 people present in them, including individuals accompanied by children or other family members. Findings indicate that water collection constitutes a routine activity. In four out of seven cases, individuals reported visiting multiple water sources in search of availability. These efforts often involved lengthy, 3-kilometer journeys over sandy terrain while carrying heavy loads, with water supply being inconsistent. In two interviews, respondents indicated that they pay individuals with household taps to access water, highlighting financial constraints and continued dependence on external sources. Only one interviewee reported having a private tap at home, a rare circumstance often associated with safety concerns.

To provide an embodied understanding of the challenges associated with water access, a brief interactive simulation was developed. This experiential game, available during the coffee break, utilizes updated Google Street View imagery to simulate the journey undertaken by residents in search of water. Participants are invited to virtually traverse the same sandy roads, endure the perceived heat stress, and comprehend the distances that must be covered daily. While engaging with the game, participants are encouraged to reflect on the logistics of transporting water from public taps to their homes.

Research Framework

Research goal:

Our goal is to help local stakeholders prioritize where and how to improve water access — especially for the women as the most affected group.

Research outcomes:

To do this, we created a data collection tool, which enables local stakeholders to gather and input the necessary information into a database that feeds the dynamic vulnerability and impact maps.

Outcomes

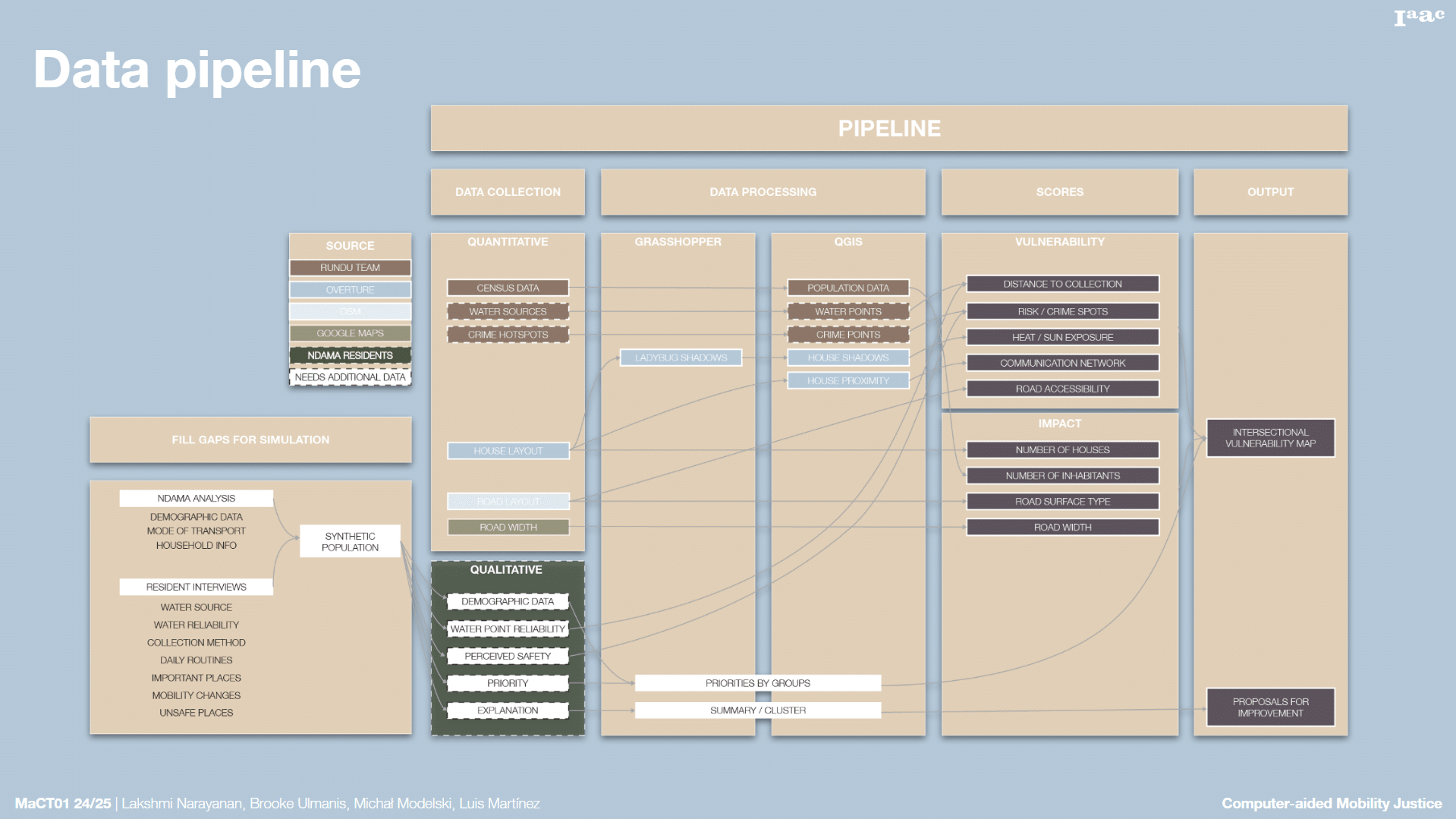

Research Metholodgy & Pipeline

Mapping Water-Related Vulnerabilities

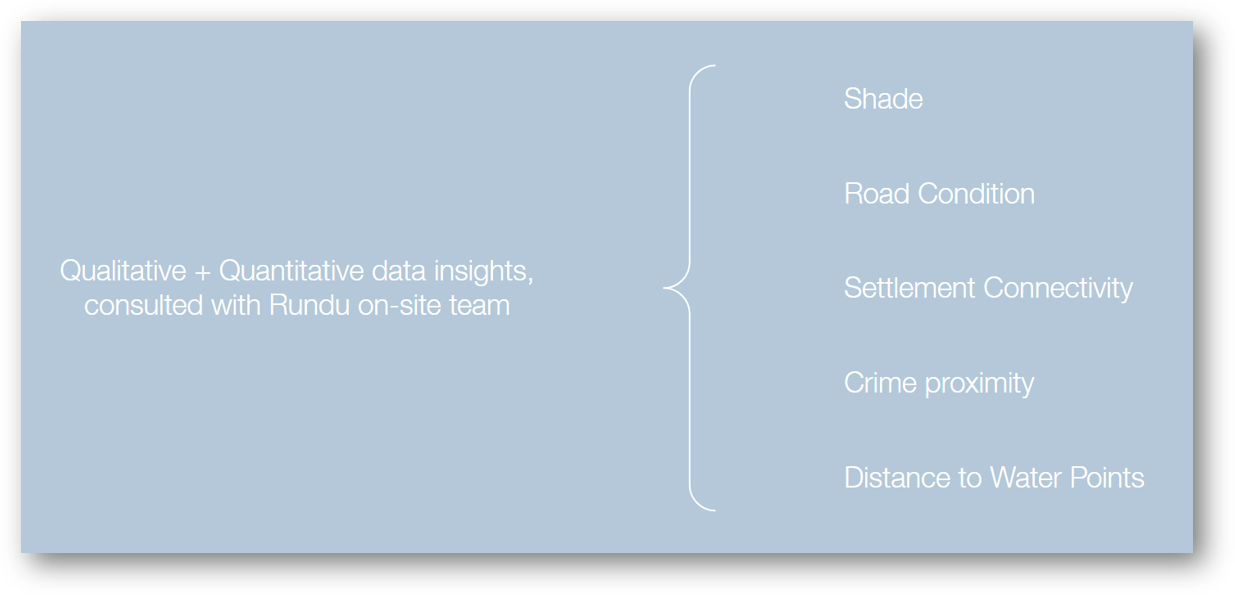

To map water-related vulnerabilities in Ndama, we integrated both qualitative and quantitative data obtained through collaboration with the on-site team in Rundu and through our conducted interviews. From this analysis, we identified five key categories contributing to mobility-related vulnerability in the context of water collection: availability of shade, road conditions, settlement connectivity, proximity to crime-prone areas, and distance to water sources.

01. Shade Analysis (Remote Assessment)

This category considers environmental features such as buildings and trees exceeding 10 meters in height, which provide shade along pedestrian pathways. These shaded areas play a significant role in reducing heat exposure during water collection.

02. Road Condition (Remote Assessment)

We evaluated the type of road surface within a 500-meter radius to determine accessibility. Gravel roads were prioritized, as they enable easier pedestrian movement and the possibility of taxi transport. In contrast, sandy roads are typically avoided by taxis, reducing mobility options.

03. Settlement Connectivity (Remote Assessment)

Due to the absence of an official registry or network for tracking functional water sources, we used the spatial distribution of housing clusters as a proxy for communal connectivity. This approach allowed us to approximate how information regarding water availability may circulate within the community.

04. Crime Proximity (Local Knowledge)

Areas with high crime rates were identified as zones that residents actively avoid, thereby exacerbating their vulnerability. A notable example is the pension distribution point, which becomes a hotspot for theft due to the concentration of cash transactions, posing particular risks for elderly individuals.

05. Distance to Water Points (Local Knowledge)

Lastly, we created a distance map using 500-meter buffer zones around known water points to highlight areas with more accessible water sources. This spatial representation helps identify zones with relatively easier or more constrained access to water in Ndama.

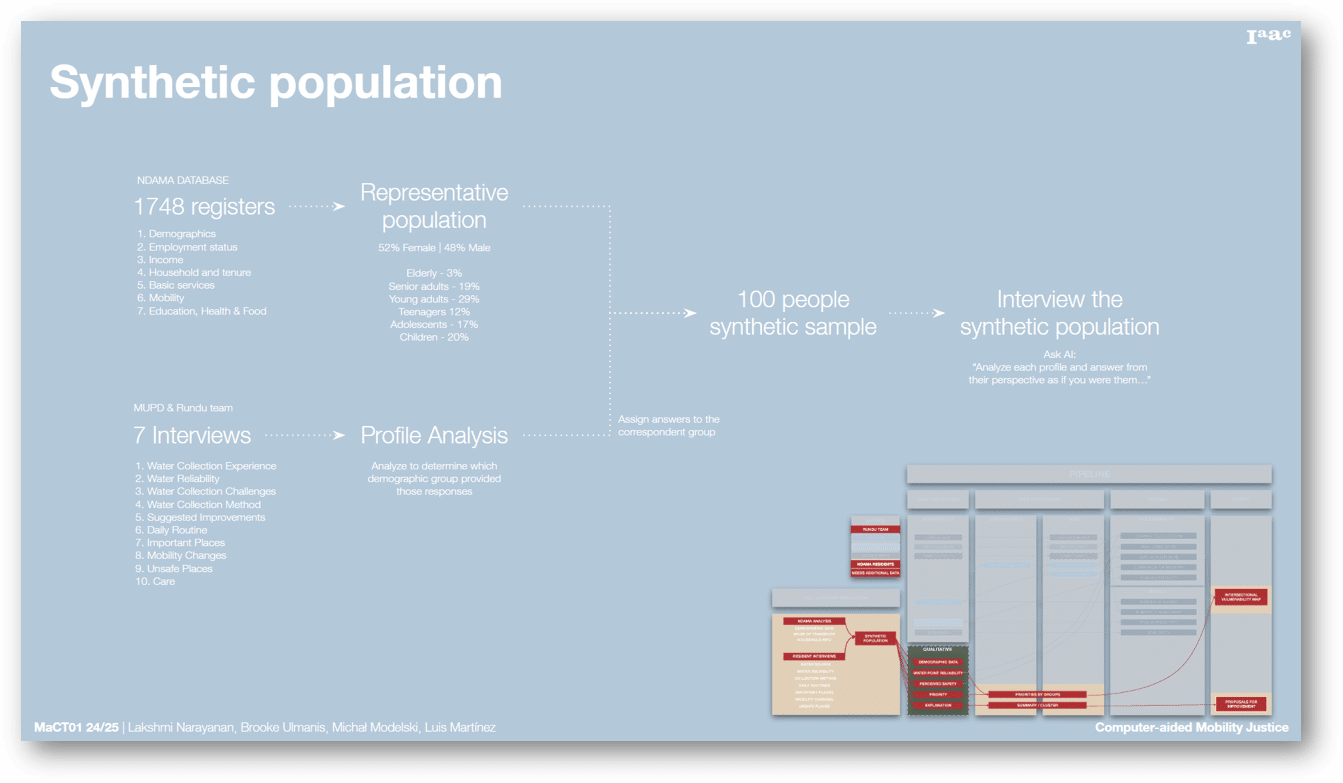

Synthetic Population

To simulate the functioning of our tool using data as close to reality as possible, we developed a synthetic population to temporarily stand in for real data from the residents of Ndama that we don’t have at the moment. A key feature of the synthetic population is that it is statistically representative: each synthetic individual or household reflects real-world characteristics, such as age, gender, income, location, and household size, drawn from existing census or survey datasets.

For this purpose, we utilized a dataset provided by the Integration Group in Rundu and GIZ Consultants. This dataset includes information from 1,748 households across East and West Ndama and spans seven key categories. These variables allowed us to construct statistically representative profiles of the community. In parallel, we sought to understand residents’ perspectives on water collection and accessibility in Ndama.

With support from Martha Siyamba, we conducted interviews with seven residents: two men and five women, ranging in age from approximately 20 to 60 years old. The interview consisted of nine open-ended questions. The responses were then matched to similar profiles within the synthetic population. This process enriched our personas by adding a qualitative layer reflecting lived experiences and opinions about water-related challenges.

Once the personas were created, we employed artificial intelligence to simulate the voices of these interviewees. The AI analyzed their profiles and responses and generated realistic interactions to demonstrate the capabilities of our data collection tool. While the synthetic population enables us to carry out a simulation grounded in local realities, it is essential to acknowledge the inherent biases in this approach. The results generated by the AI are limited by the assumptions and constraints of the data. Our goal is not to replace the voices of Ndama’s residents but to illustrate how our tool could operate using realistic input. Ultimately, the tool’s true potential is realized through the use of real data and the active participation of the community.

Open Source Platform

RunduTrack

Next Steps

Throughout the development of this methodology, several limitations and biases were identified:

Limitations

- The effectiveness of the platform relies heavily on the availability of extensive data and the active participation of Ndama residents, to ensure an accurate representation of both vulnerability and its impacts. However, the community’s limited access to digital devices posed a significant constraint. As a result, our approach necessitated the physical collection of data by an external individual, which in turn implies the need for funding to support this labor-intensive task.

- Moreover, there remains potential to incorporate additional layers of vulnerability. For instance, integrating road width as a proxy for accessibility could further refine our analysis.

Biases

- Assumption bias: The model assumes an average household size of four residents. While useful for simulation purposes, accurate, geo-referenced population data would significantly enhance the precision of our vulnerability mapping.

- Several biases were inherent in our simulation model.

- Coverage bias: Our interviews were conducted with a limited range of demographic groups, excluding crucial perspectives from children, adolescents, and the elderly.

- Synthetic data bias: Some spatial data—such as water collection from leaking pipes—were simulated using randomly generated locations. While this randomness attempts to mimic real-world behavior, it may not fully capture actual usage patterns.