Introduction

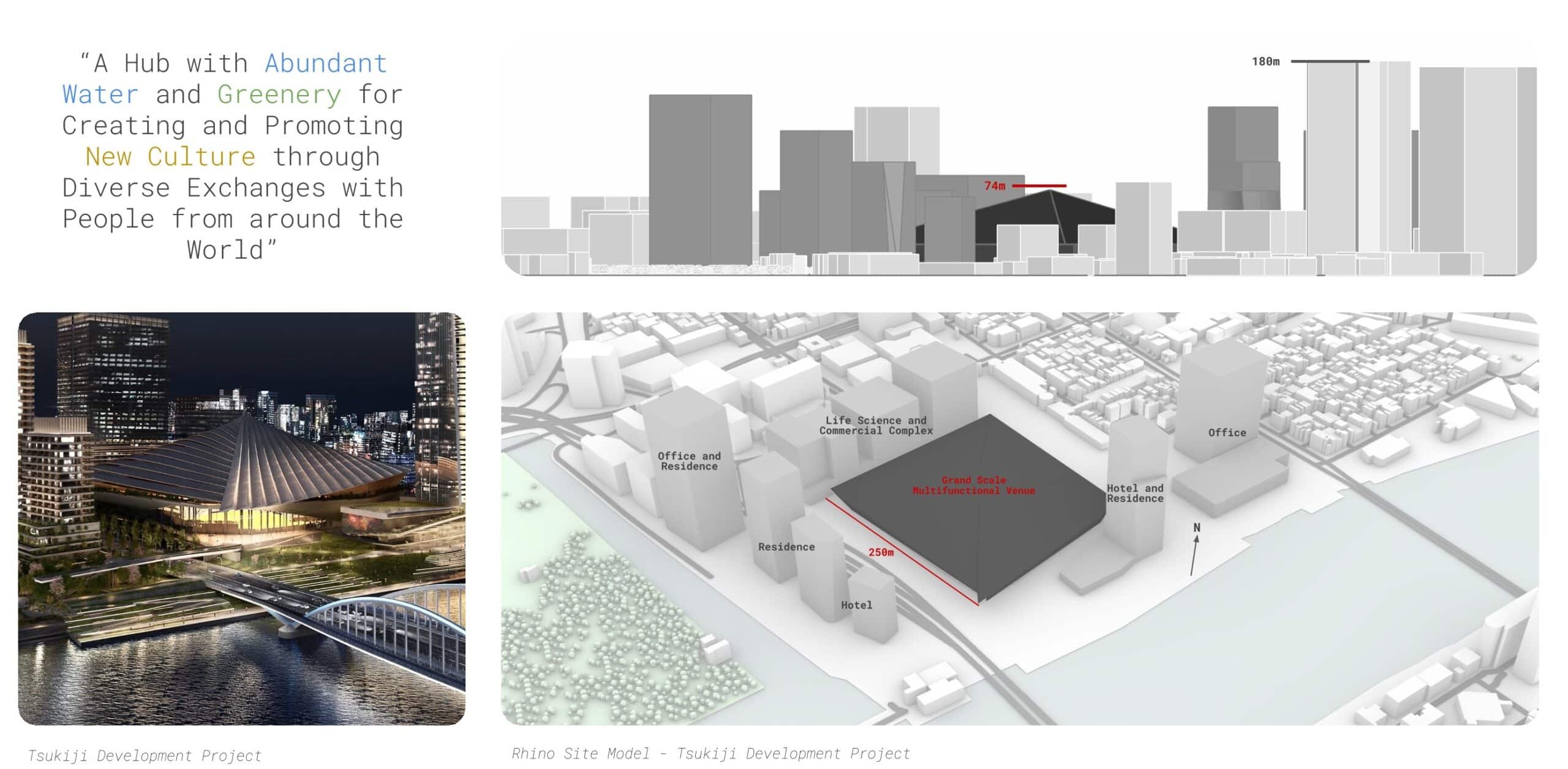

Group Async A, comprised of Charles Abi Chahine, Emilie El Chidiac, María Sánchez, and Lakzhmy Zaro, conducted an environmental analysis of a redevelopment project in Tokyo, Japan. We focused on a 19-hectare plot that was historically the site of the Tsukiji fish market.

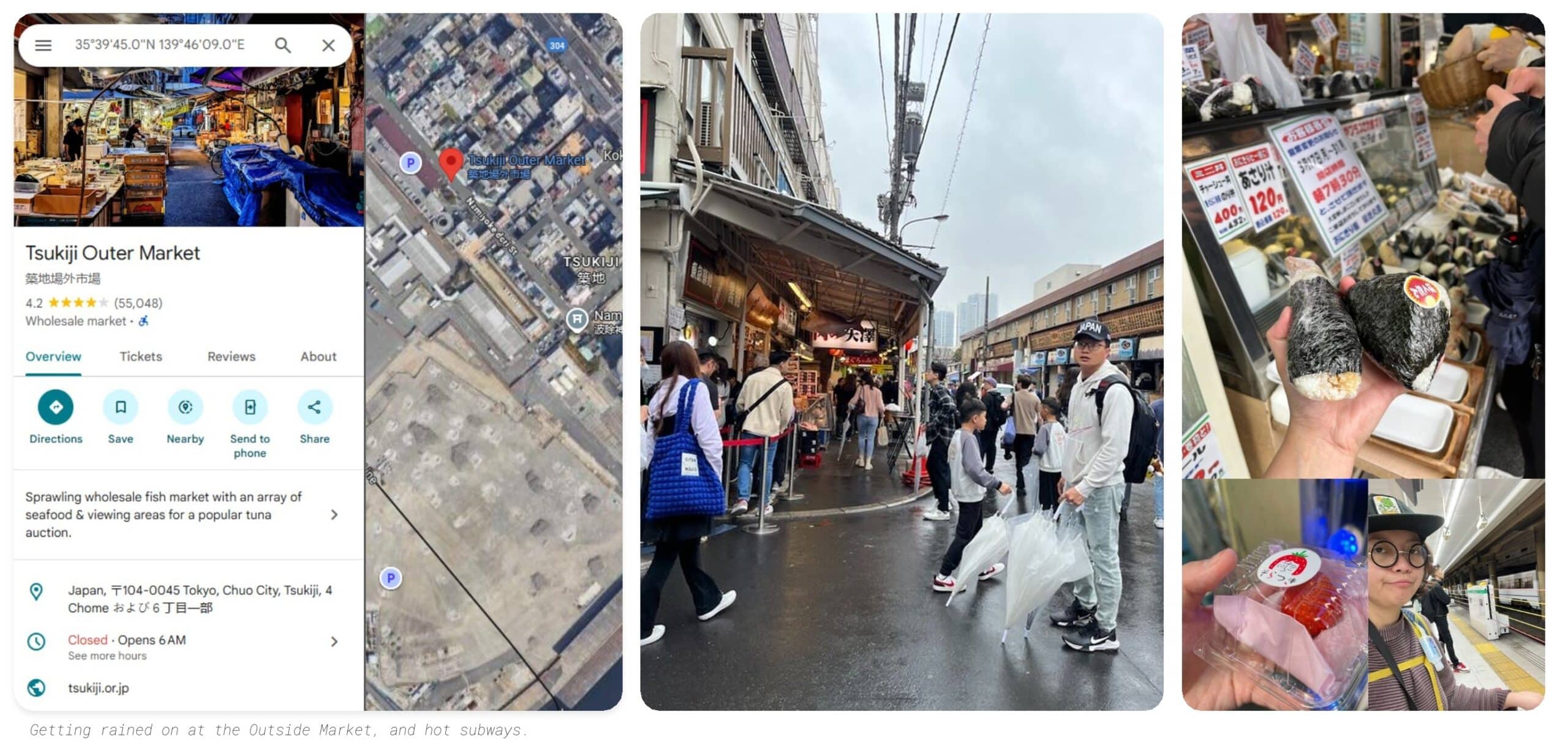

The Challenge of Dressing for Tokyo

Anyone who has visited Tokyo’s famous Tsukiji fish market knows the challenge of dressing for the city’s climate. I recall a trip where my outfits were perpetually wrong for the weather, which swung between “wet and cold and sometimes hot and humid” in the space of a day.

This personal experience highlights a much larger architectural challenge. If it’s difficult to simply dress for Tokyo’s weather, imagine trying to design a 19-hectare multifunctional venue for it. This was the task at hand for a new development proposed for this famous site. A deep environmental analysis of the project, using advanced digital simulations, was conducted to understand its performance. The findings revealed several counter-intuitive lessons about urban design in an extreme climate.

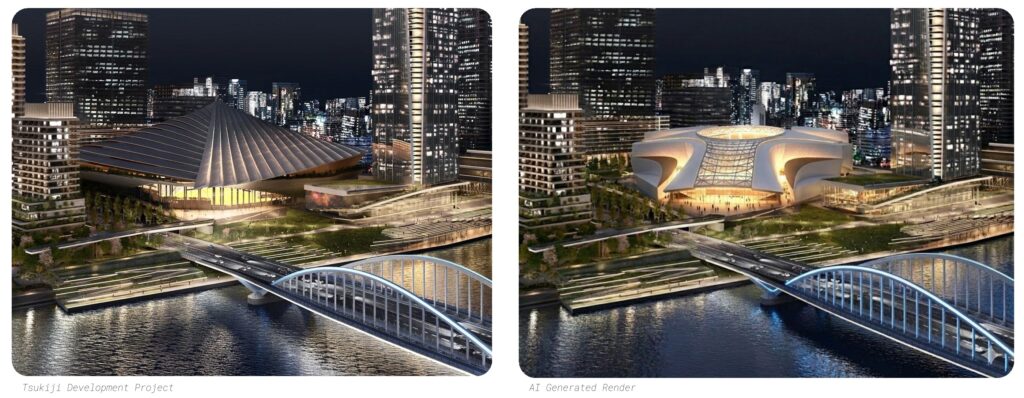

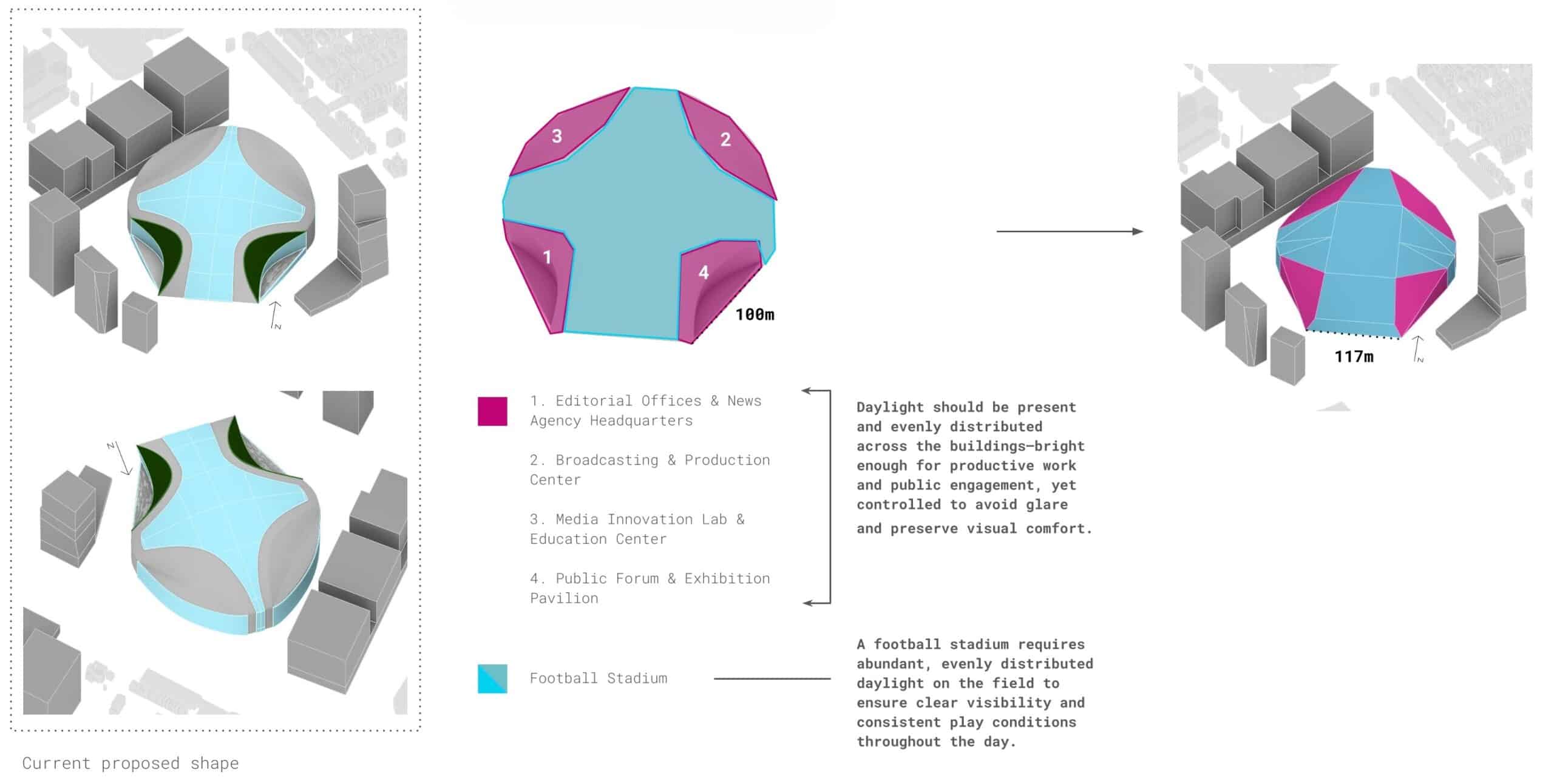

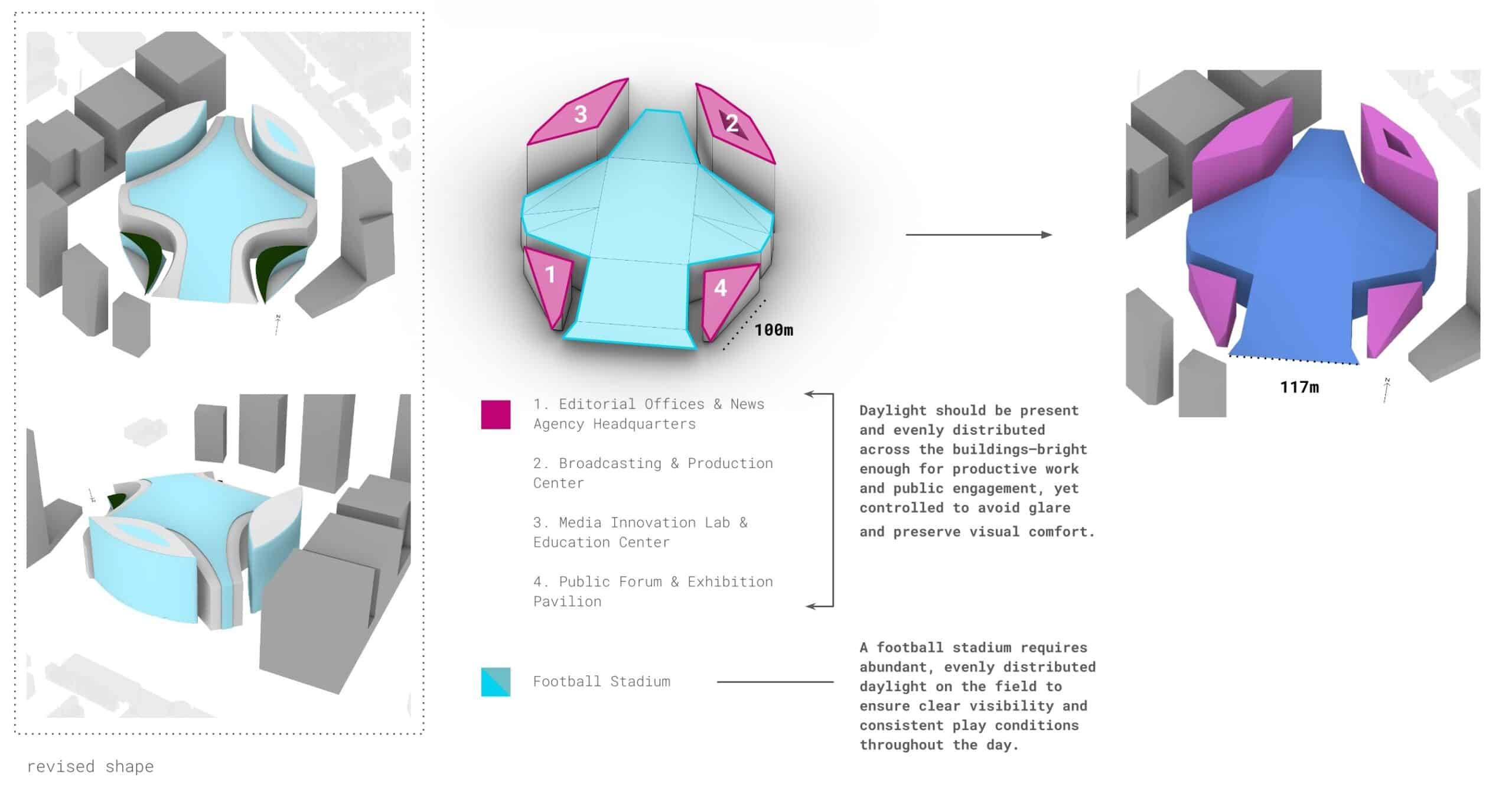

The existing proposal for the site is a multifunctional venue centered on wellness, innovation, food, experience, activity, and hospitality.

Climate Constraints

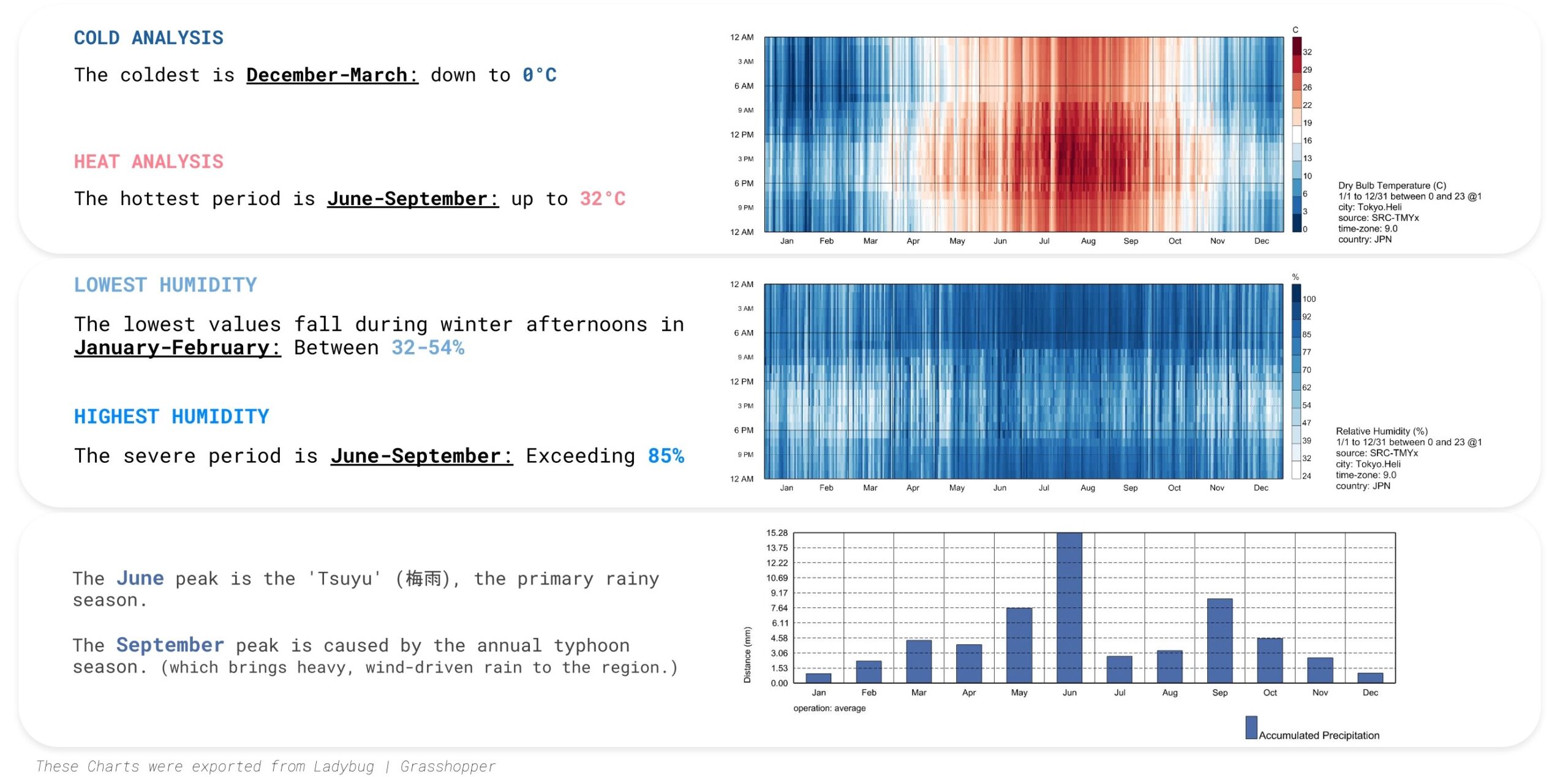

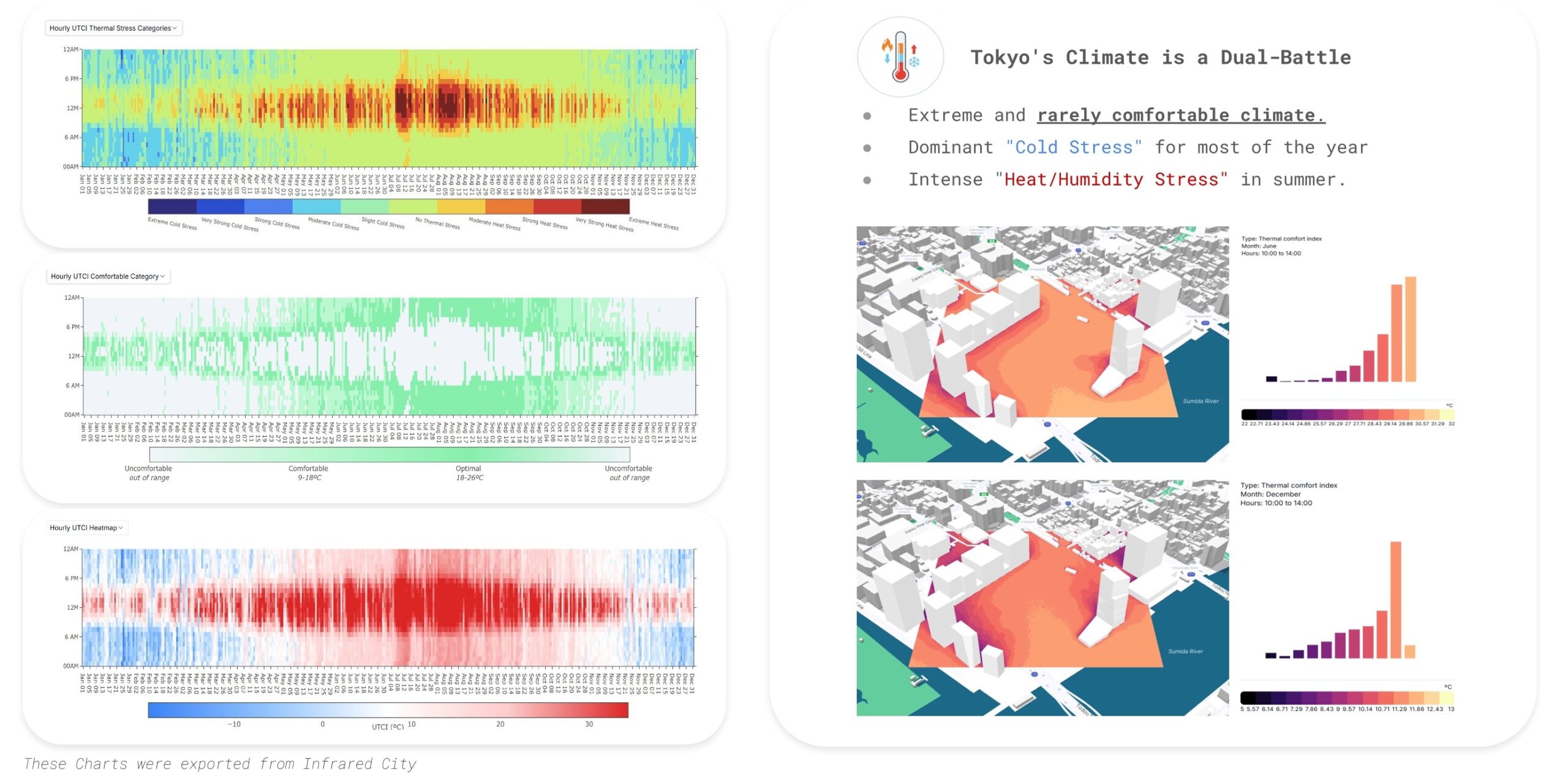

Our analysis addressed Tokyo’s humid subtropical climate. We identified specific seasonal extremes as primary design challenges, particularly from June to September, when temperatures reach 32°C and humidity exceeds 85%. Our microclimate analysis suggests that Tokyo presents a “harsh” climate where total comfort requirements are rarely met. This creates a “dual battle” for the site: it faces cold stress during the winter and significant heat trapping during the summer.

Methodology

We utilized Ladybug and Infrared.City to analyze the pre-existing urban development. Our process included several key steps:

1) Site Climate Analysis

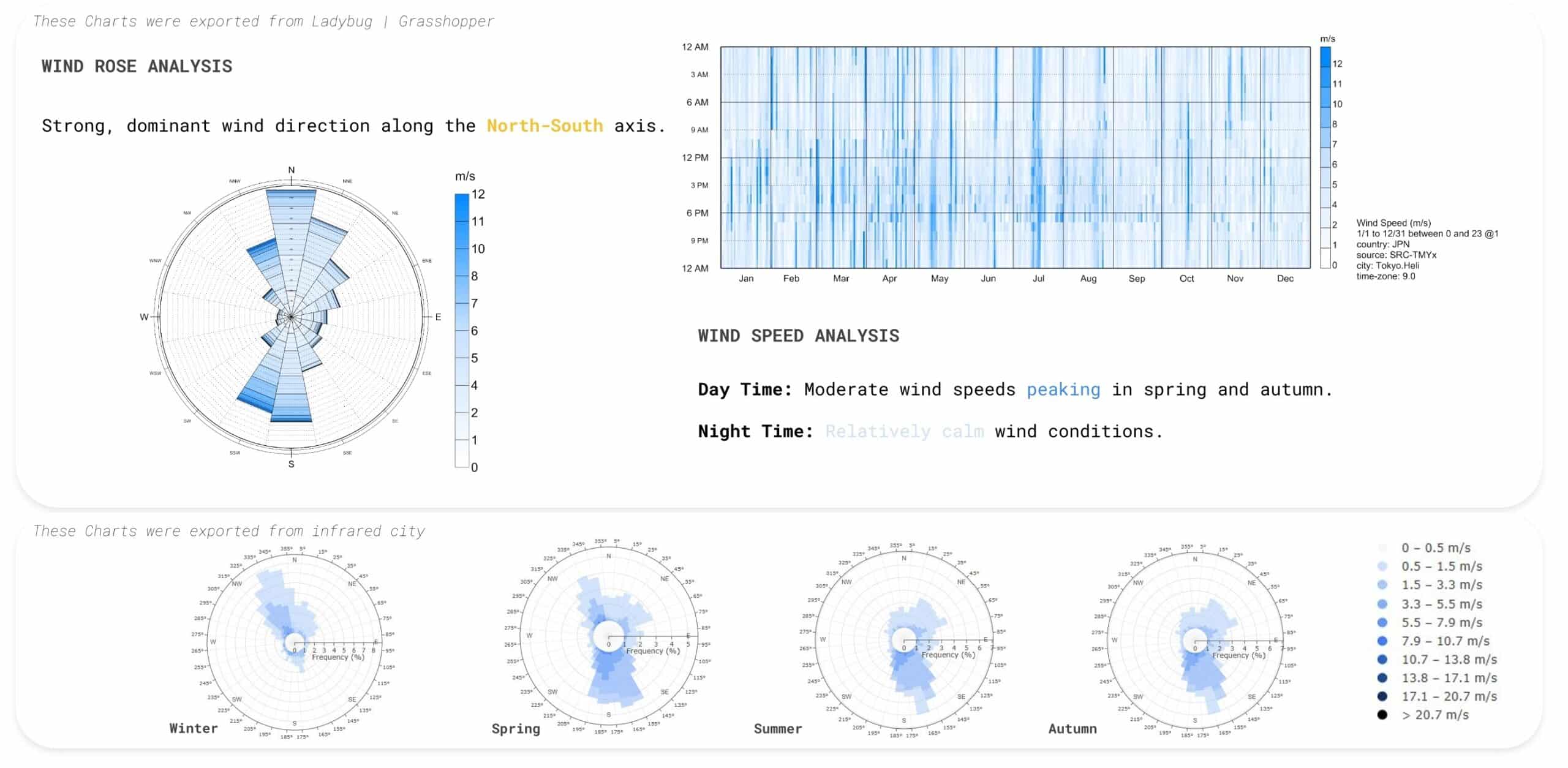

• Wind Mapping: We mapped a dominant wind direction along the North-South axis to understand airflow through the site.

• Thermal Stress Analysis: We used Infrared.City to pinpoint exactly when and where the site suffers from thermal stress, establishing a baseline for outdoor comfort.

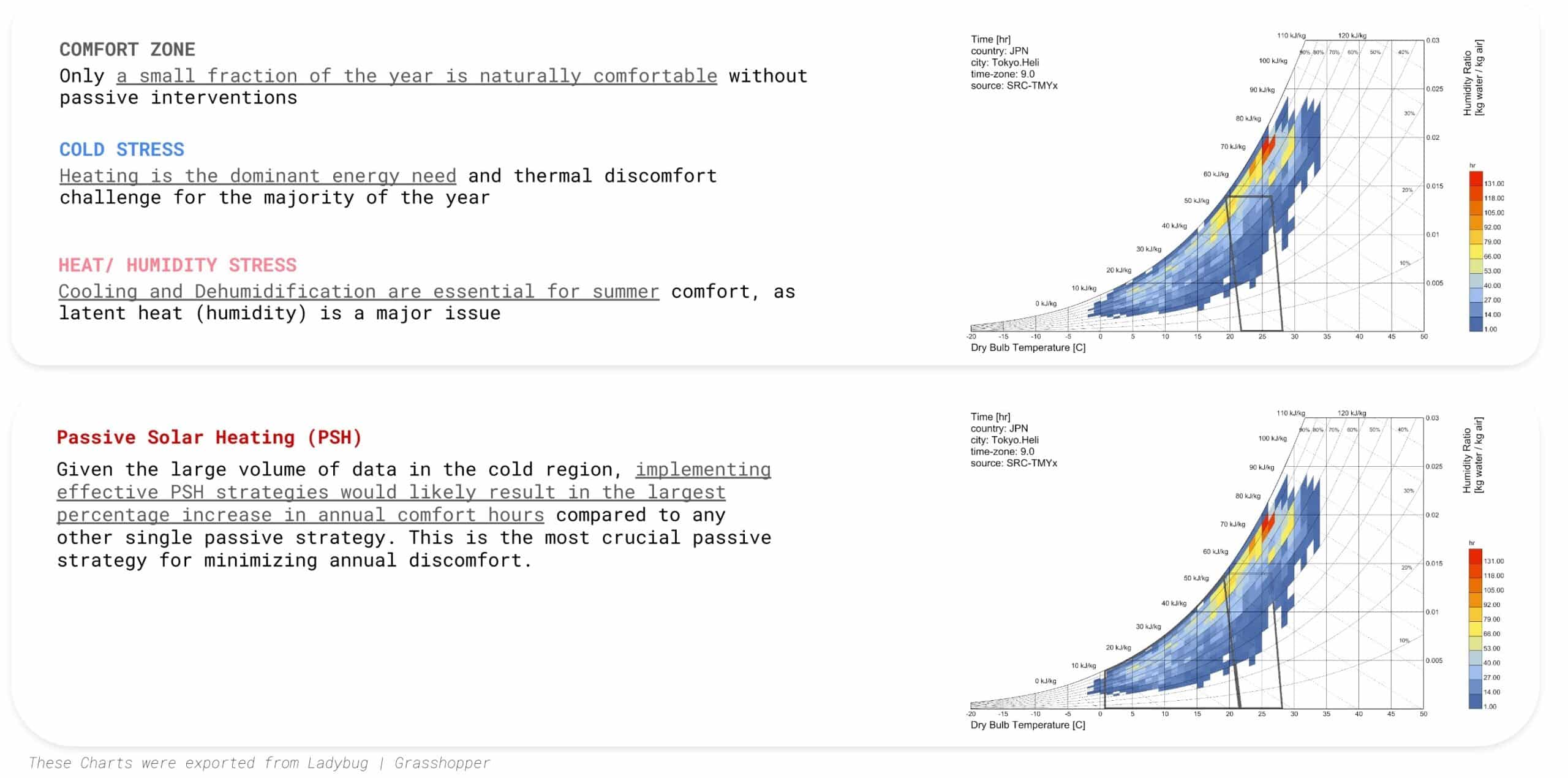

• Psychrometric: The analysis derived from the chart suggests that implementing Passive Solar Heating (PSH) is the most crucial strategy. This single intervention would likely result in the largest percentage increase in annual comfort hours compared to any other passive strategy.

2) Development Environmental Behavior Analysis

Once Tokyo and the specific site have been analyzed to understand their climatic characteristics, we move onto the assessment of the architectural development that is being constructed. This project will be analyzed through a series of lenses (radiation, daylight comfort, UTCI, multiobjective iterative analysis…) and for every assessment, we develop a new formal iteration to combat the found shortcomings in the proposal.

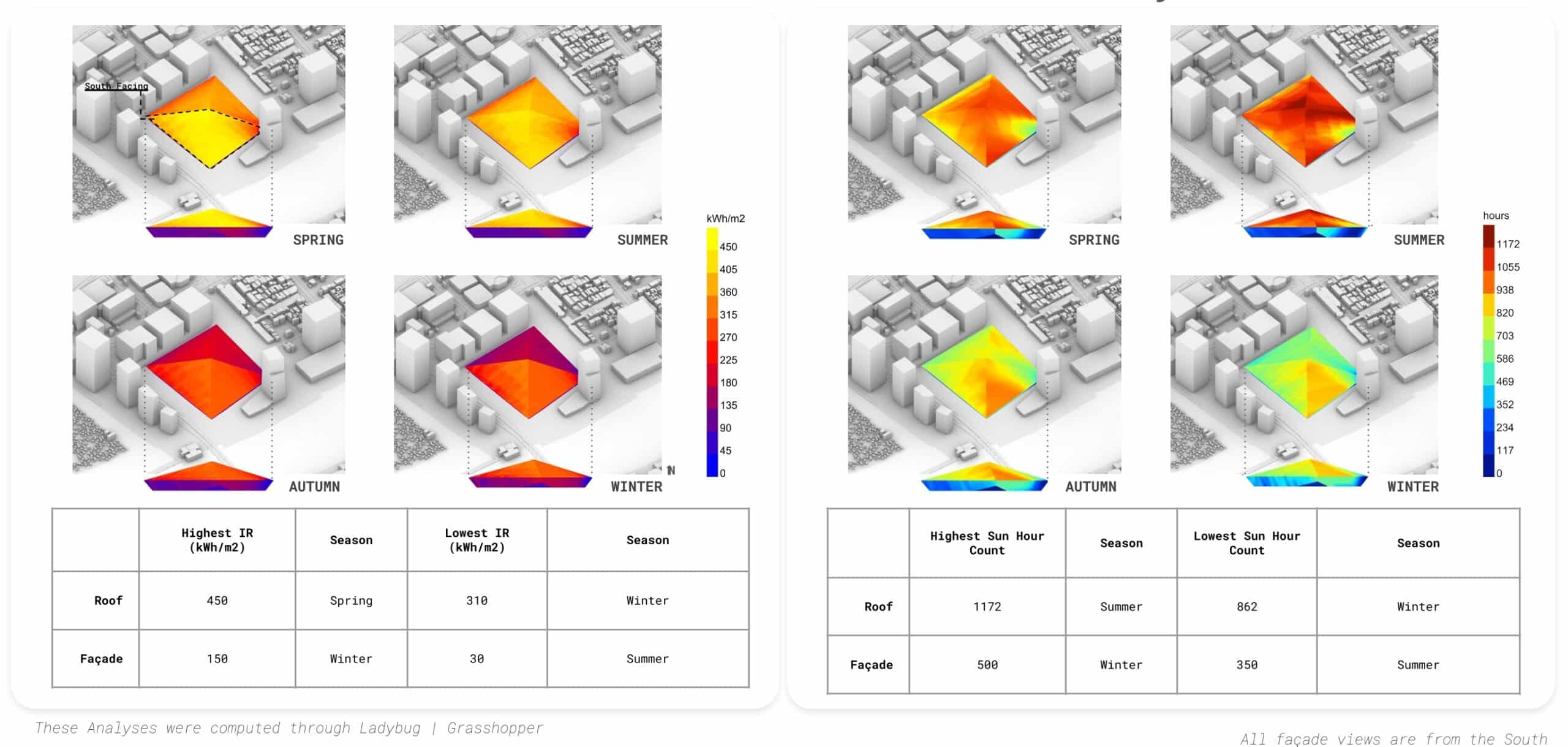

• Solar Analysis: We conducted an incident radiation and direct sun hours analysis on the initial shape, which motivated modifications to the roof to improve energy efficiency and cooling airflow.

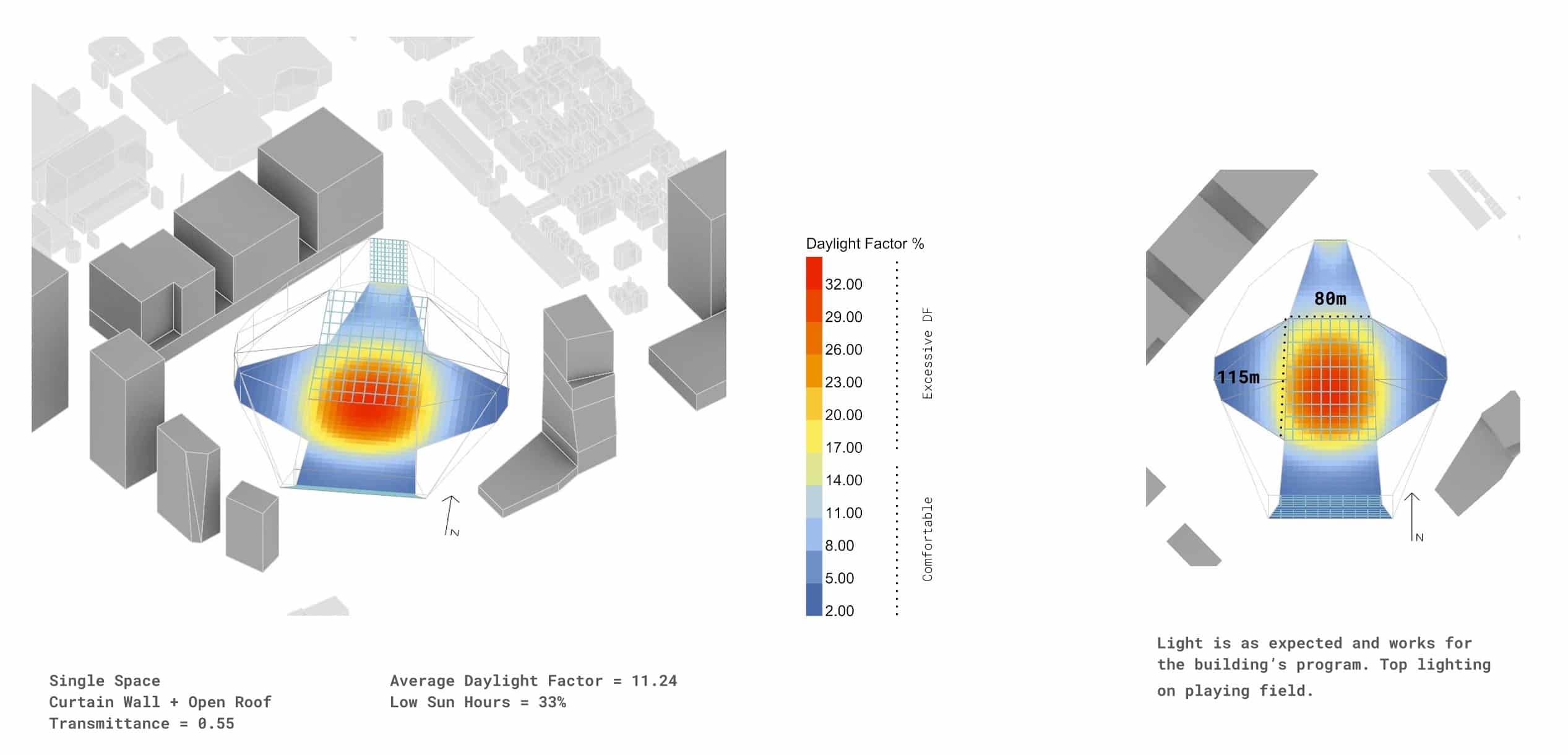

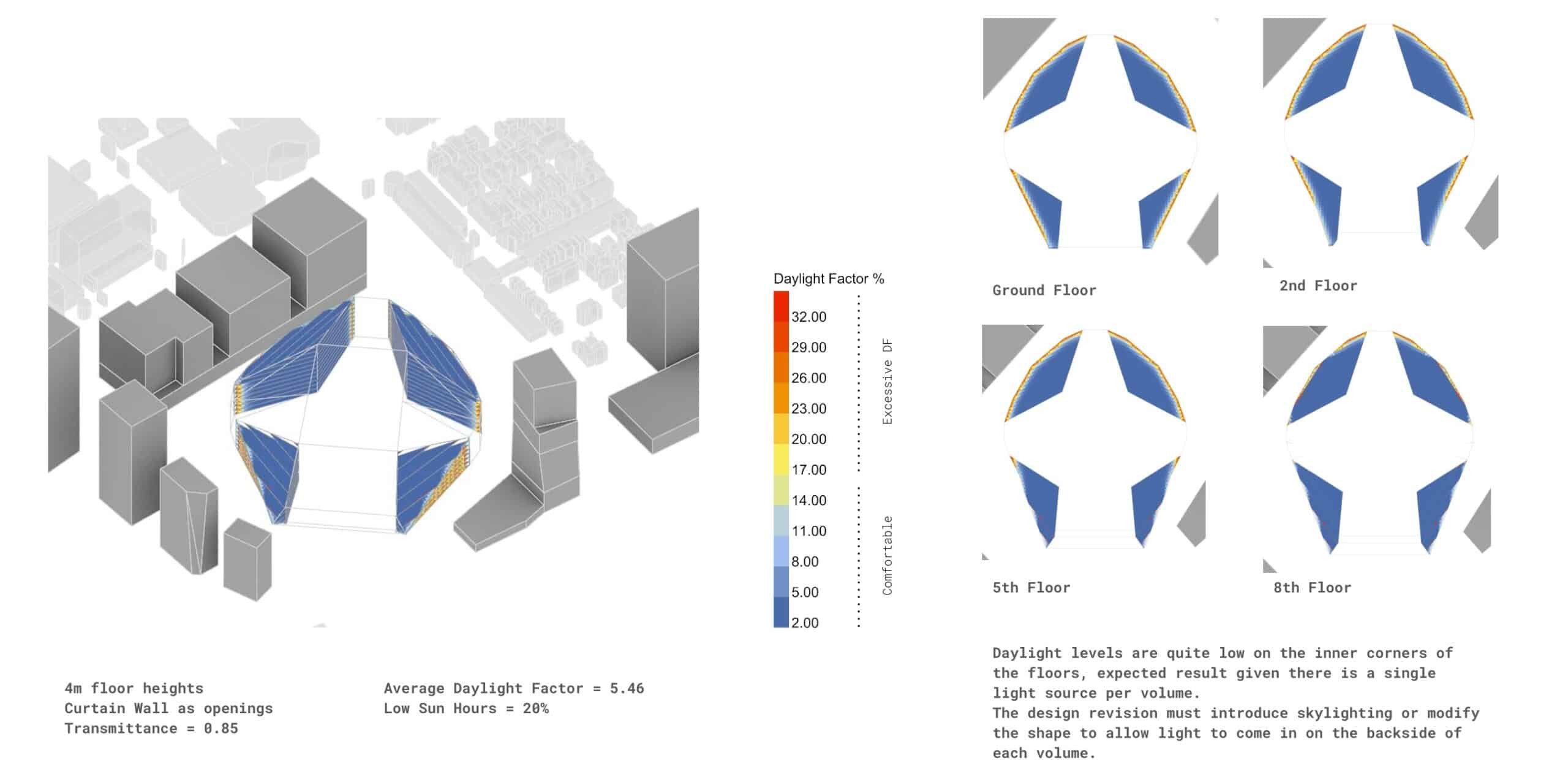

• Daylight Comfort: We evaluated interior daylight conditions by distinguishing between the two main programs of the building: the stadium in the center and the office buildings on the sides.

Findings and Iterations

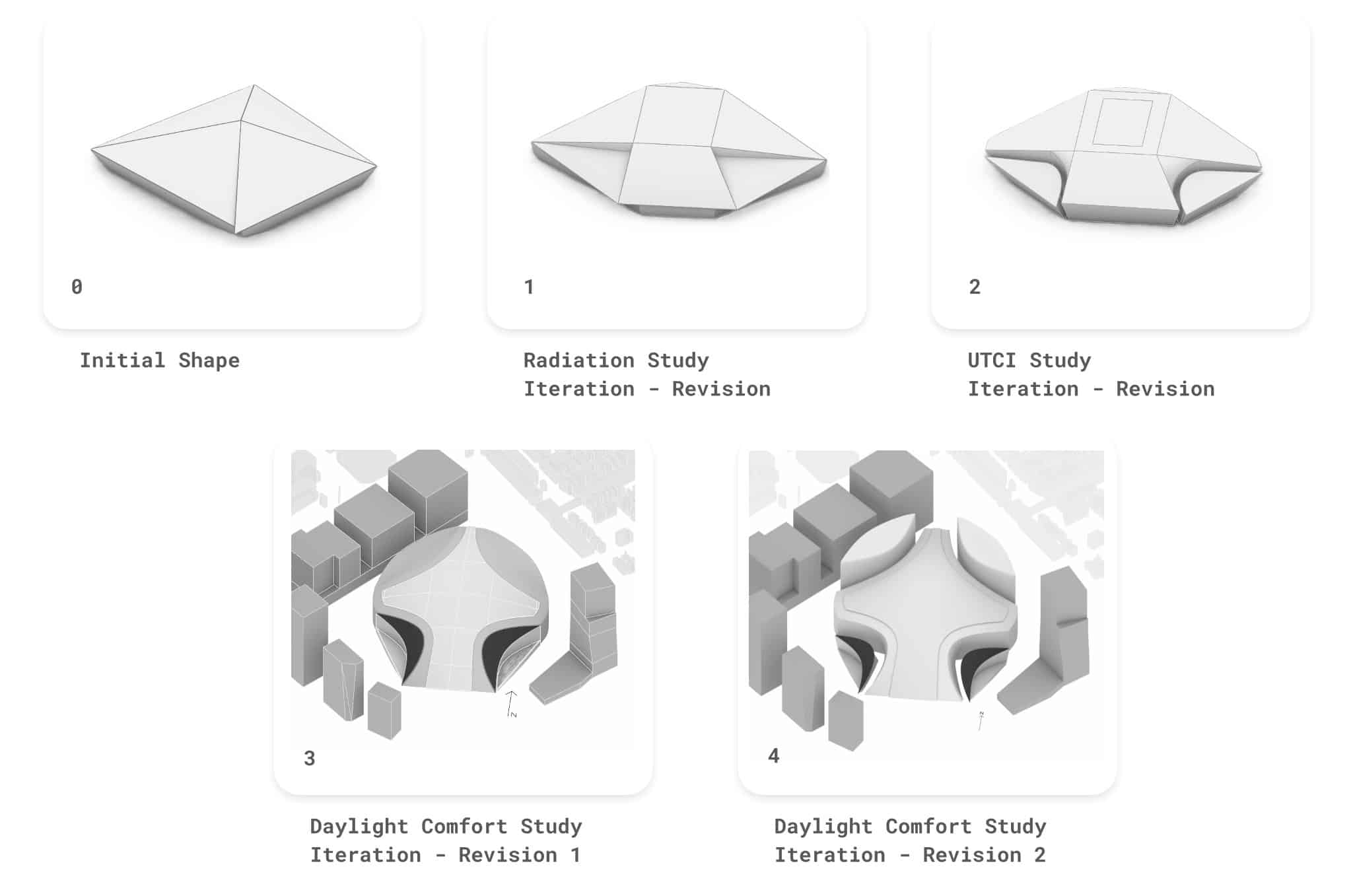

As a summary, the formal changes introduced throughout the diverse analyses are the following:

As a final step, to fully optimize the design, we established a validation loop using Infrared.City and Galapagos to fact-check our massing against a full 360-degree rotation. Our findings included:

• Wind Speeds: The site is naturally well-shielded, with mild annual wind speeds averaging 1.5 m/s.

• Orientation: Our simulation results indicated that the building’s original orientation was the statistical winner for maximizing airflow.

• Thermal Comfort: While 88% of the area performed well, we identified specific courtyard zones that trapped heat in the summer.

Conclusion

Ultimately, we concluded that Tokyo’s climate presents dual challenges: the city remains cold for most of the year but shifts to being hot and humid during the summer months. Our initial hypothesis was that minor modifications to the original form would suffice, but our analysis proved that these changes had minimal impact on environmental performance.

The data exposed clear shortcomings in exterior thermal comfort, compelling us to implement significant shape revisions rather than slight adjustments. Specifically, to mitigate the heat-trapping effects we identified in the courtyards, we altered the scale of the towers surrounding the stadium and populated the zones where heat lingers with trees.

However, the news wasn’t all bad. We found that the project actually performs well in orientation, interior daylight, and wind resistance without major intervention. We wrapped up our project by rendering our optimized design to visually compare how these data-driven decisions improved upon the existing development.