Through Human-Centered Spaces and Experiences

In a world that is rapidly urbanizing itself, architecture holds immense power to shape the lives of individuals and how they experience the public space. Yet, architectural design often neglects the various needs of the community it is supposed to serve, leading to alienation and exclusion, particularly for marginalized populations. This thesis explores the concept of designing for empathy through architecture, investigating how built environments can become inclusive and empowering spaces for all.

Focusing on wearable technologies and immersive experiences, the research examines how tools like sensor-based devices and user-centered design principles can be leveraged to bridge the gap between architecture and human experience. By redefining traditional design frameworks to incorporate diversity and accessibility, this study explores new models for inclusive public spaces that actively respond to the needs of individuals, from the homeless to the disabled.

Through prototyping and speculative design, this thesis argues that empathetic architecture and body-centered design is not only possible but essential for fostering equity, but most importantly insuring dignity and connection in our urban environments. The ultimate goal is to demonstrate how design innovation begins with the human body, and it can be used to challenge systemic alienation and enable more inclusive interactions between people and the spaces they inhabit. This work advocates for design that prioritizes human-centric adaptability, transforming public spaces into empathetic environments that reflect the richness of human diversity.

–

Introduction & Context

Main issue: architectural alienation and hostile design

Impact: marginalized groups, particularly the homeless in urban settings

–

Research question:

–

How can realtime physiological data from the human body be used as a sensor to quantify and map urban comfort levels, and what insights can this provide for human-centered design?

–

Hypothesis:

By using real-time physiological data from the human body, we can map urban comfort levels across a city, revealing hidden stress zones and optimizing urban design for collective wellbeing. The human body functions as a living sensor, turning the body into a new ground for architectural innovation, while the city becomes a second skin that reflects the physiological and emotional responses of its inhabitants.

–

Aims

- Challenge and denounce hostile and alienating architecture

- Advocate for inclusive public spaces for all

- Explore concepts like wearable design and the human body in relation its environment

–

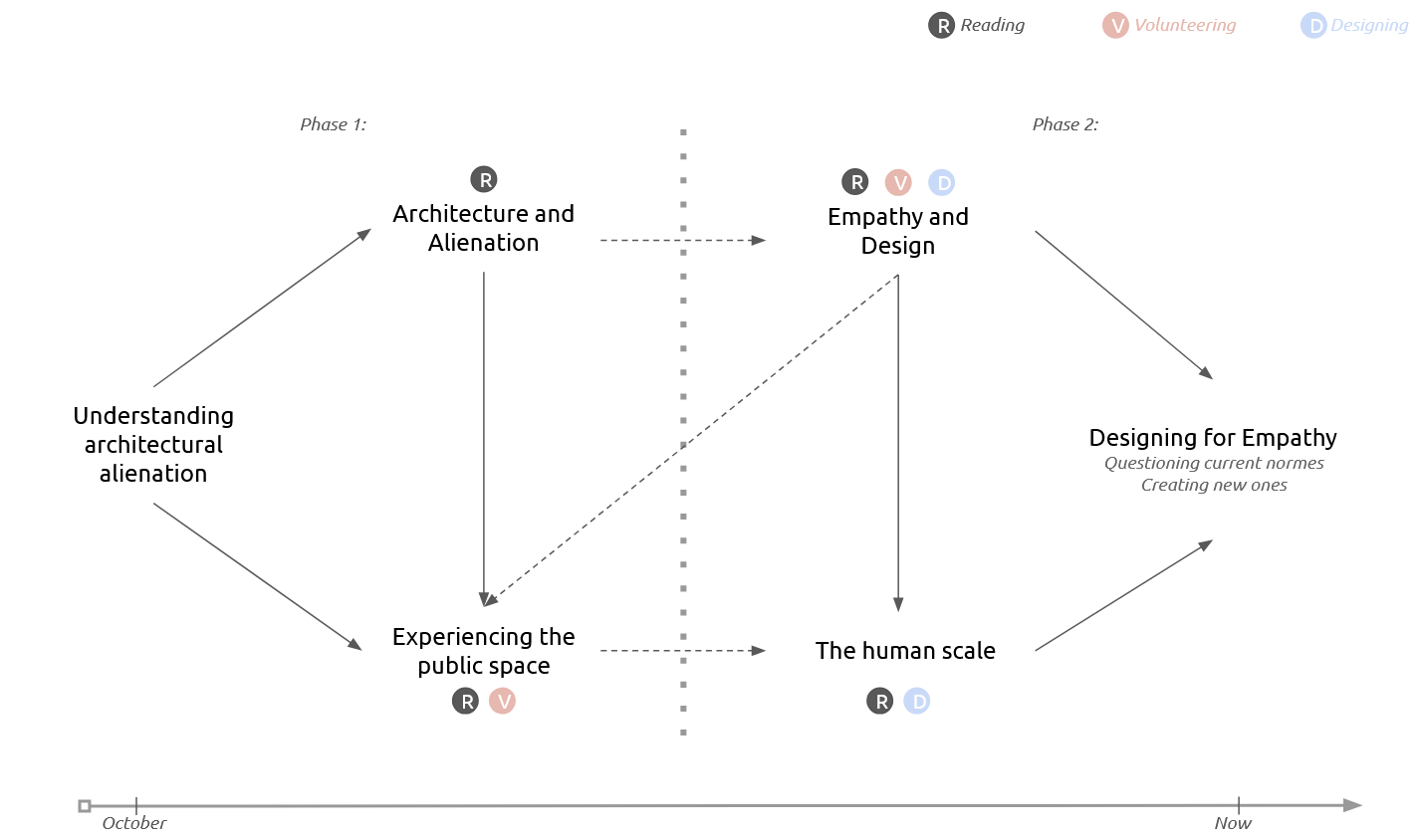

Research framework:

–

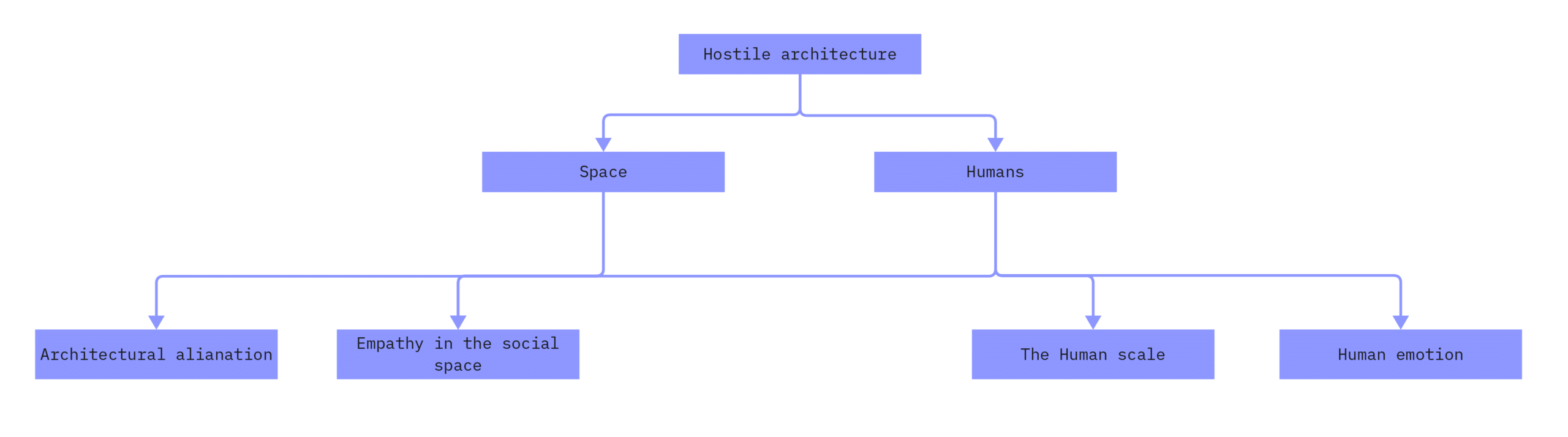

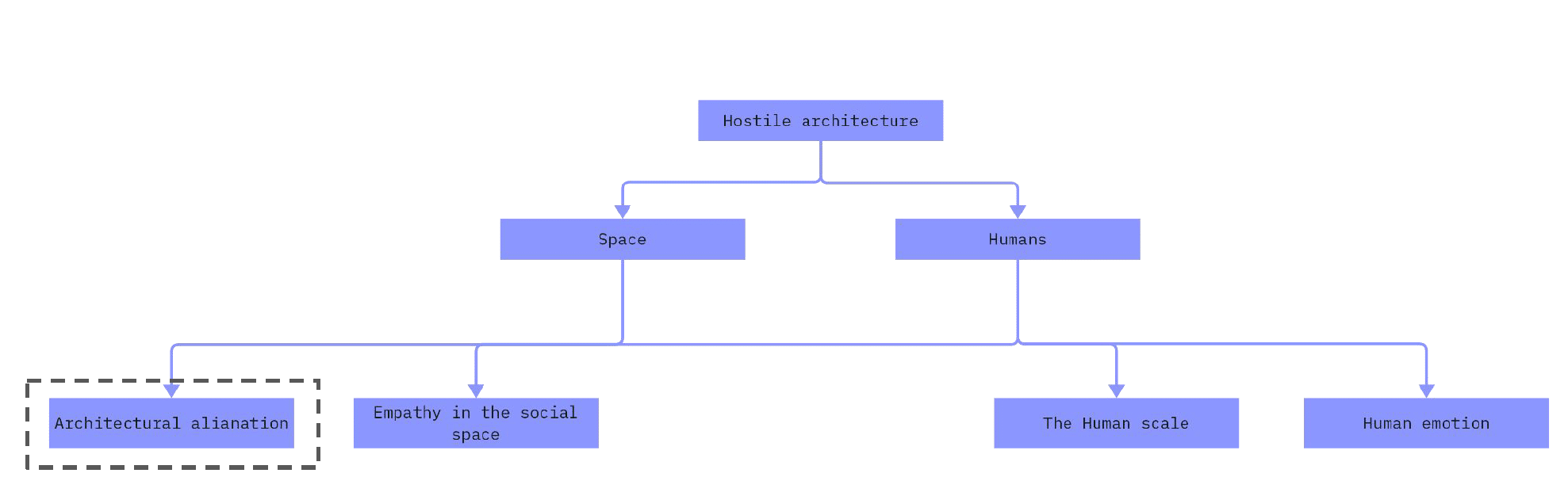

Understanding comfort

1. Architectural Alienation

1.1.Hostile design

Hostile Design: design elements in public spaces that are intentionally created to discourage certain behaviors or groups of people, such as the homeless, from using those spaces.

Forceful measures:

Mildly defensive measures:

1.2. Architectural Alienation: a layered issue

- Hostile architecture impacts all users, not just the homeless

- Prioritizes discomfort

- Erodes the communal nature of public spaces

- Promotes gentrification

- Public spaces become tools of control

1.3. HOSTILE: the social justice app

You don’t need to be a representative, a stakeholder, or a decision maker to take meaningful action. Social change does not only come from institutions, but also from individuals who are aware and engaged in their communities. This app was developed to increase awareness of social issues in one’s surroundings and to return a sense of agency to the public. It offers accessible tools for participation, making social justice work something anyone can engage in. To encourage continued use, the app includes a reward system: users receive a small incentive each time they report an issue, creating a sense of instant gratification and helping to build habits of sustained engagement.

–

1.4. The Human Bench: A radical response to hostile design

An exo skeleton that rules hostile urban furniture out of the equation completly, and turns the human body itself into urban furniture. You are now free to sit wherever you want, whenever you want. Wearing it becomes a quiet act of resistance and a powerful symbol of protest, taking a stand against the exclusionary principles of hostile design.

1.5. Hidden inclusivity bench: Turning the tools of harm into tools of inclusivity

Another approach would be to design a bench that is entirely tailored to the human body, offering a powerful counter to the exclusionary intent of hostile design. If decision-makers aim to enforce quiet animosity through their designs, we can instead embrace “hidden inclusivity,” a concept where aesthetically pleasing design choices subtly integrate inclusivity and accessibility. For example, a bench designed to follow the natural curves of the human body in various positions (lying down, lounging, sitting, etc.) would provide comfort and adaptability for all users. Such a design would not only meet functional needs but also challenge the norms of hostile architecture, proving that inclusivity can coexist with elegance and harmony in public spaces. By embedding inclusivity into the design itself, we can quietly subvert exclusionary practices and foster spaces that reflect humanity’s diversity and shared needs.

The inclusive bench prototype was handcrafted from modeling clay, then 3D scanned and digitally scaled. This process captured the essence of human touch and intuition, sculpting the bench as if shaping it to cradle the body with care.

4.2. Hidden inclusivity bench: the art of resting

–

2. Empathy in the social space

–

2.1. Edward Hall’s Proxemics

Proxemics: Edward Hall’s concept of spatial zones in regards to human comfort

2.2. Trans-Proxemics: comfort is beyond surface-level

As technology evolves at an unprecedented pace in an increasingly interconnected world, we must adapt by rethinking its role and the space it occupies in our lives during the design process. The COVID-19 quarantine revealed just how unprepared our environments were for such a shift, highlighting the need to create spaces that seamlessly integrate technology while fostering connection instead of isolation in the face of rapid change.

2.3. The emotional scale: Form follows emotion

Using the concept of proxemics as a foundation, we can create a diagram that captures the intricate relationship between human emotions and the architectural context. Proxemics, which explores how humans perceive and use space, provides a framework for understanding how spatial design influences emotional states. Architecture shapes our experiences by framing the way we interact with our environment and each other, whether through the intimacy of a cozy corner, the openness of a public square, or the alienation of a hostile urban space.

This diagram represents the connection between emotional responses (such as comfort, anxiety, or connection) and architectural elements, illustrating how environnement affects our feelings. For instance, Awe and Curiosity create Excitement, wich is reflected in spaces such as museums. Awe and Security create a feeling of Solace and peace which spaces like gardens evoque. However, when pushed to the extreme, these feelings become invasive and start to affect us negativaly: too much Security turns into surveillance, and too much Awe becomes overwhelming, resulting in feelings of intimidation, similar to what we would feel in a courthouse for example.

–

–

3. The human scale

–

3.1. Modernism’s obsession with conformity: standardized dimensions and universalized human norms

- Rooted in modernist design principles

- Design should prioritize functionality above all else

- Hyper-focuses on efficiency = overlooks deeper human complexity and its needs for versatility

- Good design must consider its impact on human behavior, cognition, and identity.

2.2. One-size-fits-all metrics: The modulor

Modernism and the Modulor:

- “idealized human form”

- Standardization

- Ableism

What would the Modulor look like today?

–

–

2.2.1. The Equalizer: understanding diverse human needs

2.2.2. The Equalizer (2.0): One-Size-Fits-one

An inclusive Python algorithm that allows you to enter your personal measurements as parameters in order to calculate recommended living space dimensions tailored to your own needs.

2.2.3. Becoming the modulor: comfort is what you make it

What if we could turn ourselves into the Modulor and measure our comfort levels in a space according to our lived experiences? By tracking environmental factors as well as emotional ones (such as a fast heartbeat and sweaty palms) we can gather data to transform living spaces into homes that embrace you like a second skin.

–

The body as the new ground

–

human-centric design: Meeting the physical and social needs of individuals while recognizing the emotional complexity of the human experience.

4.4. SHELL-ter: a nature inspired approach to mobility

This speculative prototype draws inspiration from the simplicity of nature. Rooted in the efficiency of a bird’s nest and the nomadic life of turtles, it offers a portable shelter that can be carried effortlessly. Lightweight and designed for movement, it provides a safe and comfortable refuge. This retractable design redefines mobility and shelter, allowing users to carry their space with them wherever they go.

4.3. The new tent: Freedom you can wear

Designing a wearable tent combines innovation, practicality, as well as empathy to address the needs of individuals who require portable shelter. This concept involves creating a cloak that not only provides protection from rain and cold when worn but can also transform into a full-sized tent when deployed. Lightweight, weatherproof materials would ensure durability and comfort, while collapsible and modular components would allow for easy portability and setup. Such a design could serve as a life-changing tool for the homeless, outdoor enthusiasts, or individuals in disaster-stricken areas, offering both mobility and reliable shelter. By integrating functionality with human-centered design, a wearable tent embodies the potential of design to address urgent needs with dignity and versatility.

–

–

4. Human emotion

–

Understanding the Nervous System:

The Nervous System’s reaction to its environment:

–

–

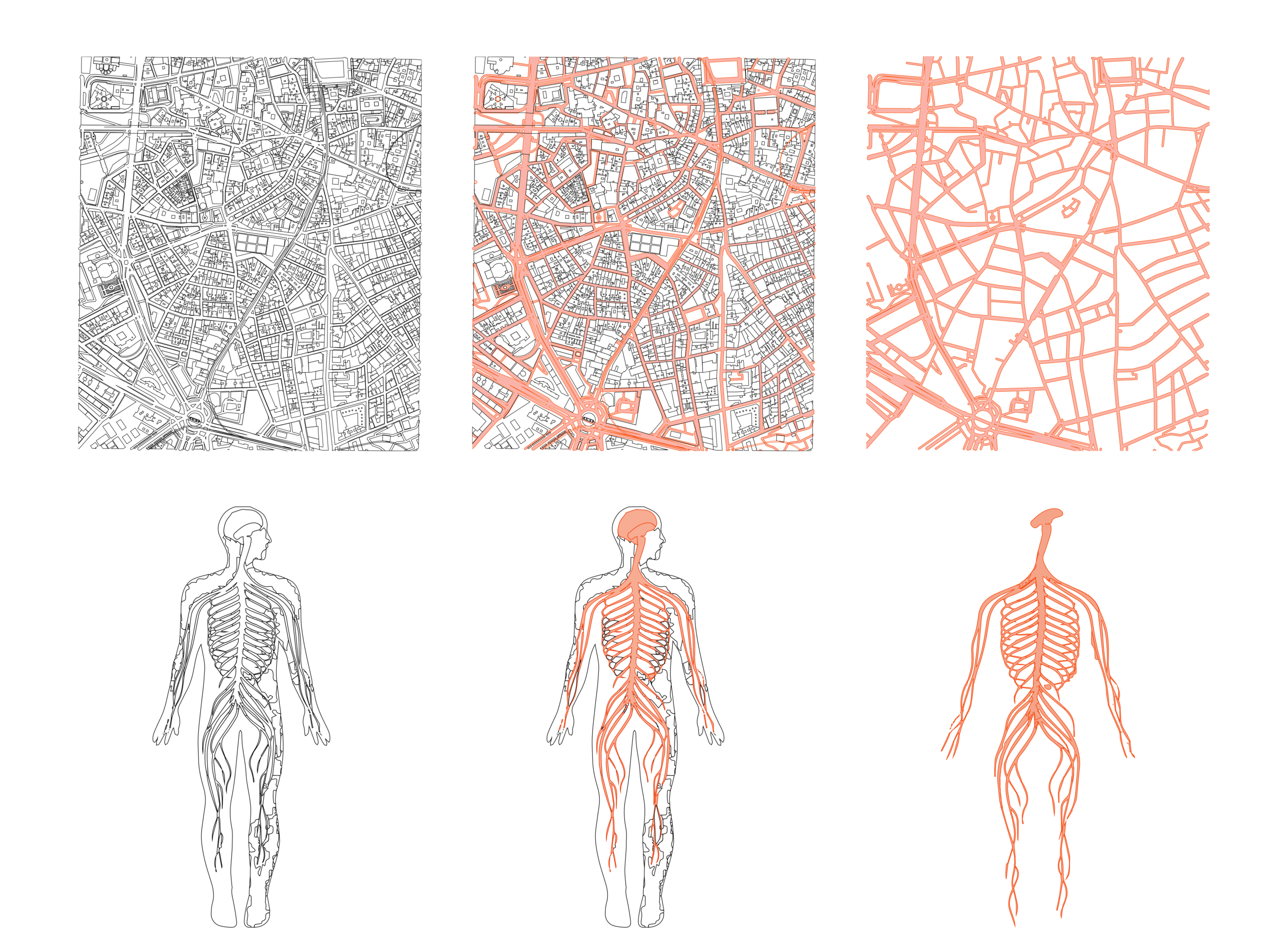

What if the city itself could become an extension of our nervous system?

Could the next evolution of urbanism be not smart cities but sentient ones?

–

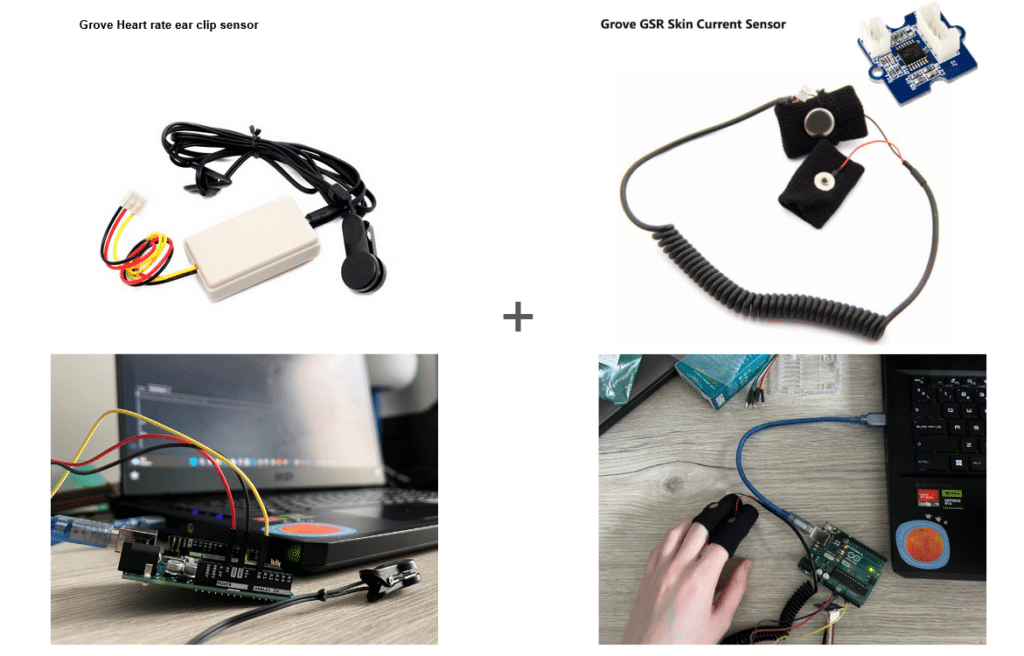

The body’s reaction to its environment: tracking & collecting data through sensors

–

–

–

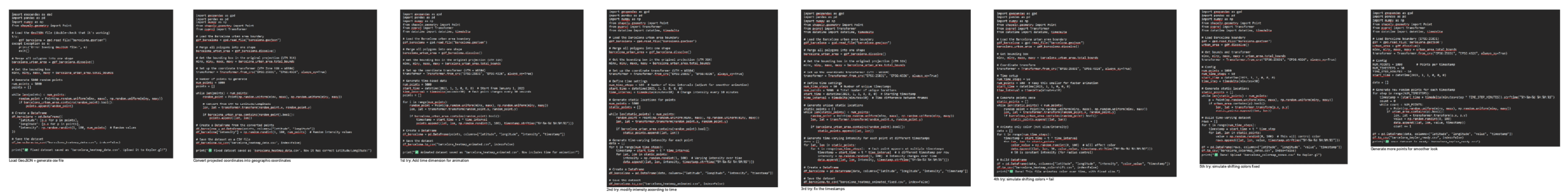

The human body as a sensor: mapping & visualizing the data

–

–

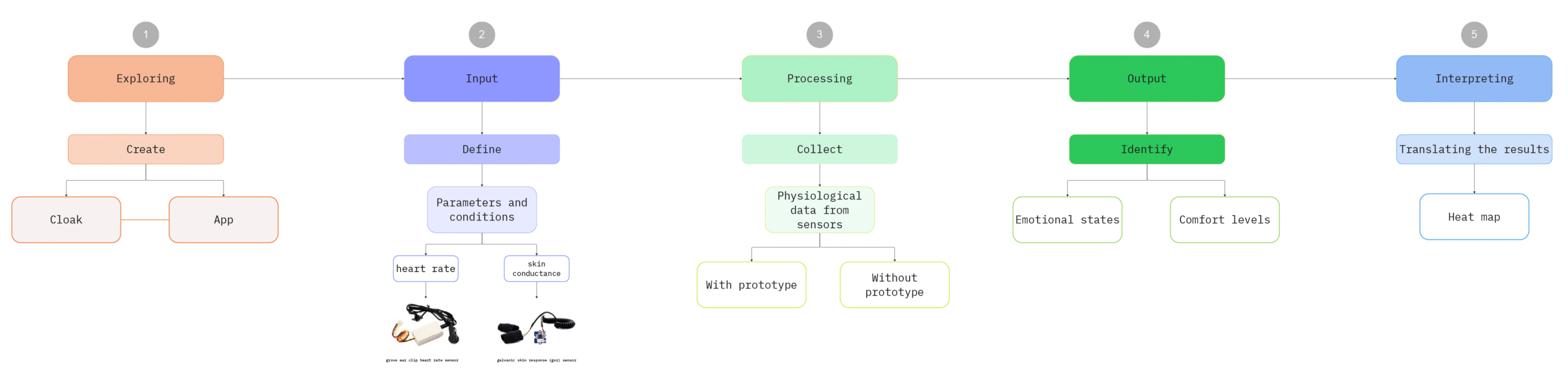

The human body as a sensor: the workflow

–