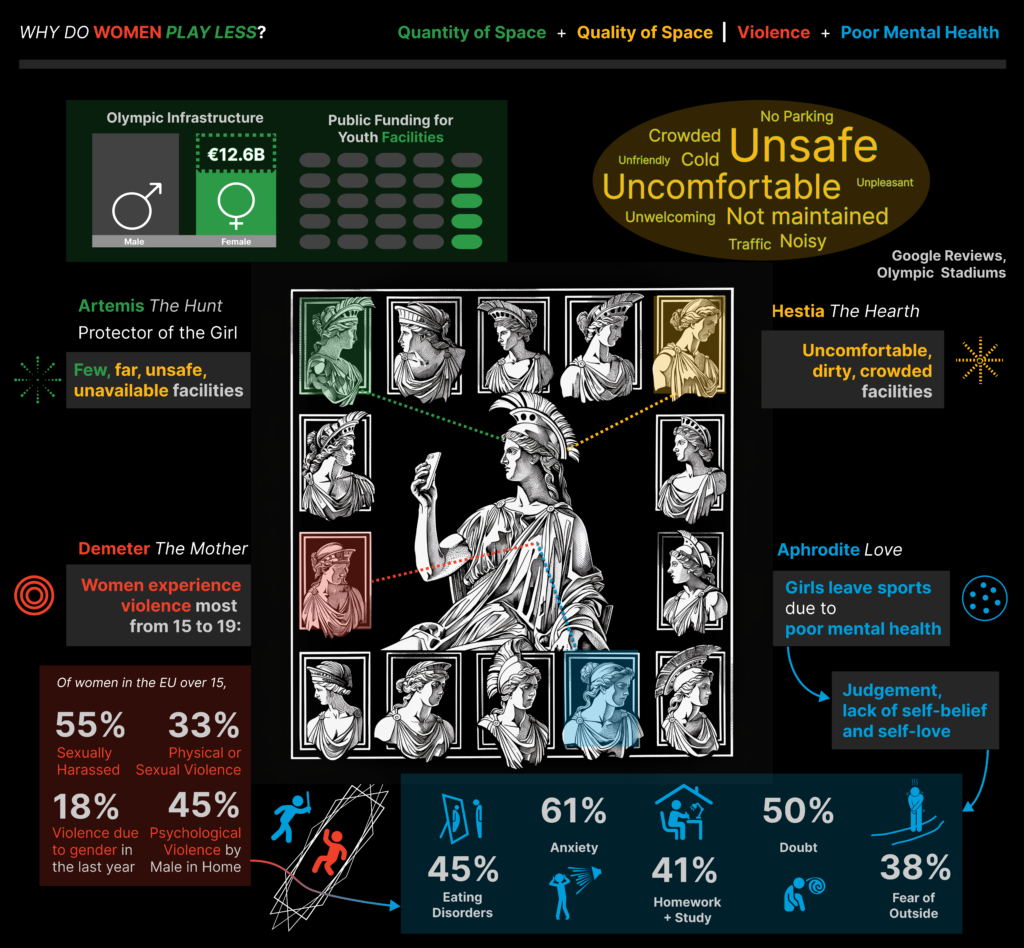

Fields at Play identifies the value of gender inequality in Olympic infrastructure and proposes to leverage the derived $12.6B Olympic gender gap in sports facilities to fund the revitalization and ongoing program of reliable, safe, and comfortable spaces for women at risk of gender-based violence.

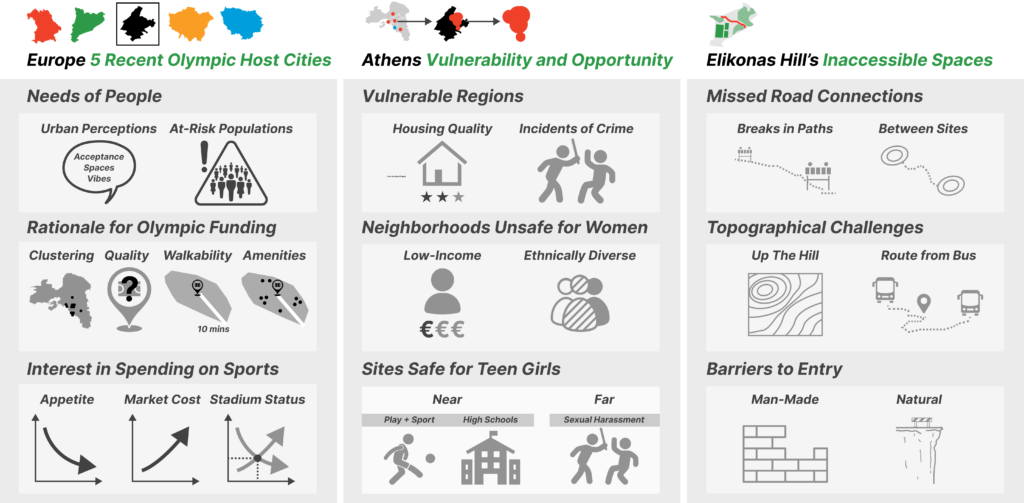

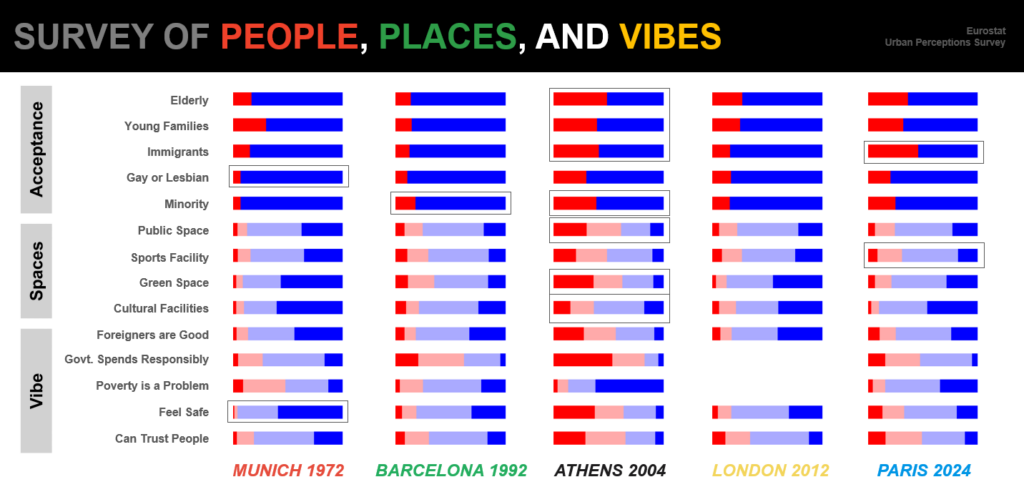

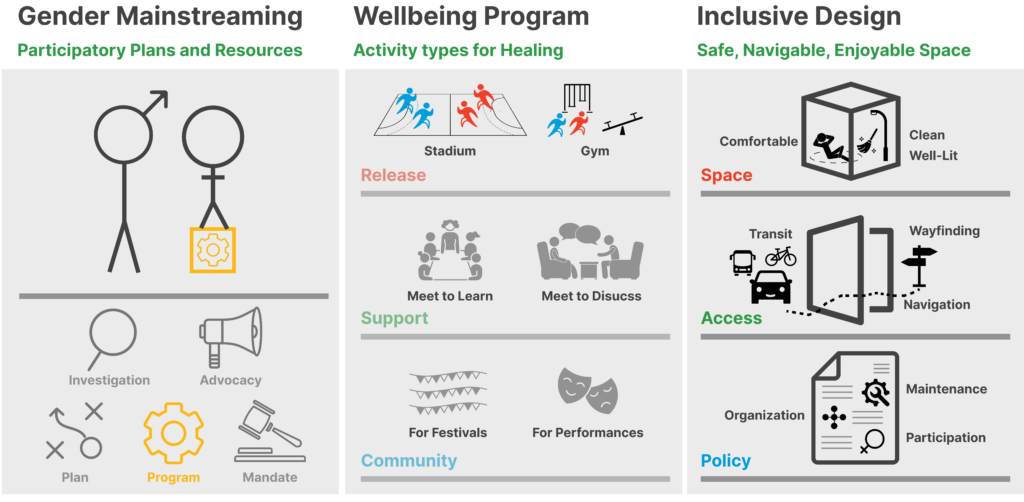

Understanding the purpose and outcomes of Olympic infrastructure strategies in Europe’s five most recent Summer Olympic host cities through their quality, clustering, and amenities for women guides regional site selection criteria and solution design. Mixed-methods case study research identified the principles of place, space, and activities that encourage reliable comfort. Findings guided a light-touch approach to site improvements and a need to segment partners between buyers of spaces and buyers of programs. a need to organize partners by type of activity and leave specificity up to the engagement process and long-term facilitate release, support, and community.

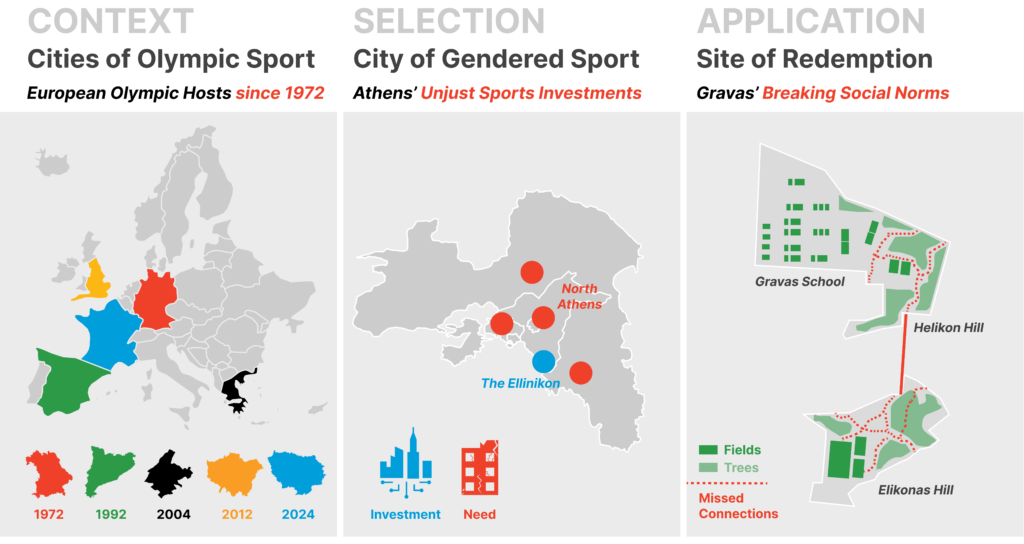

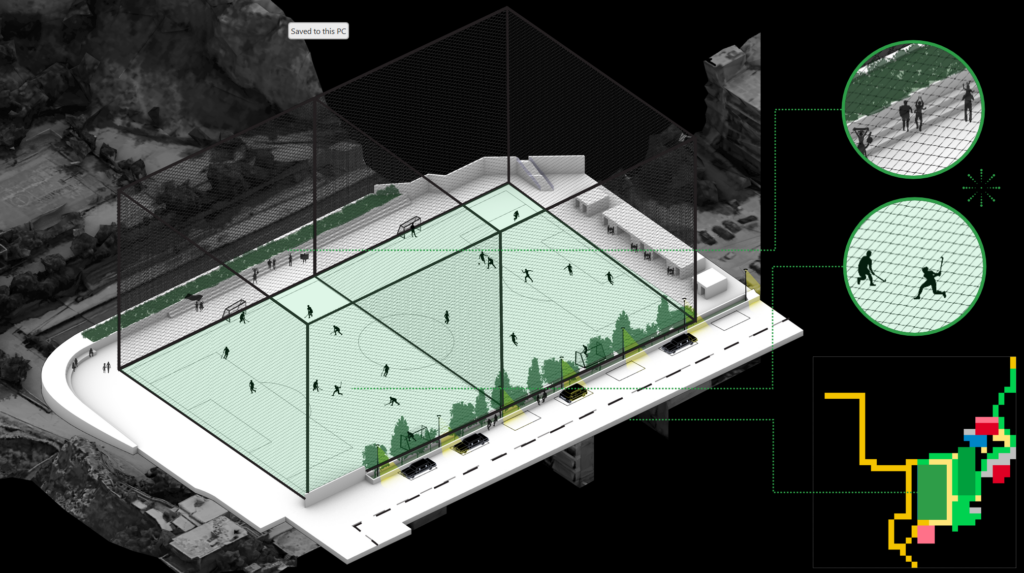

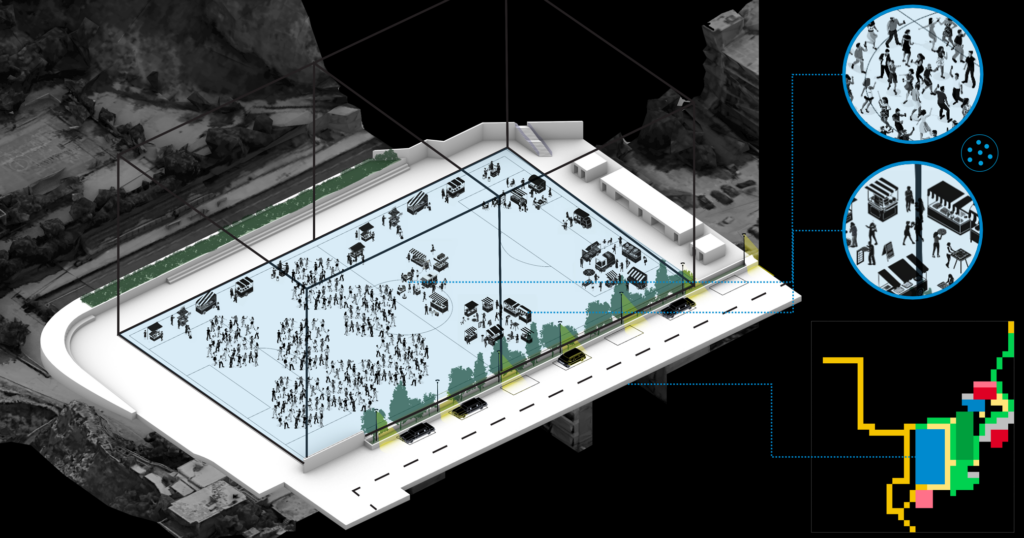

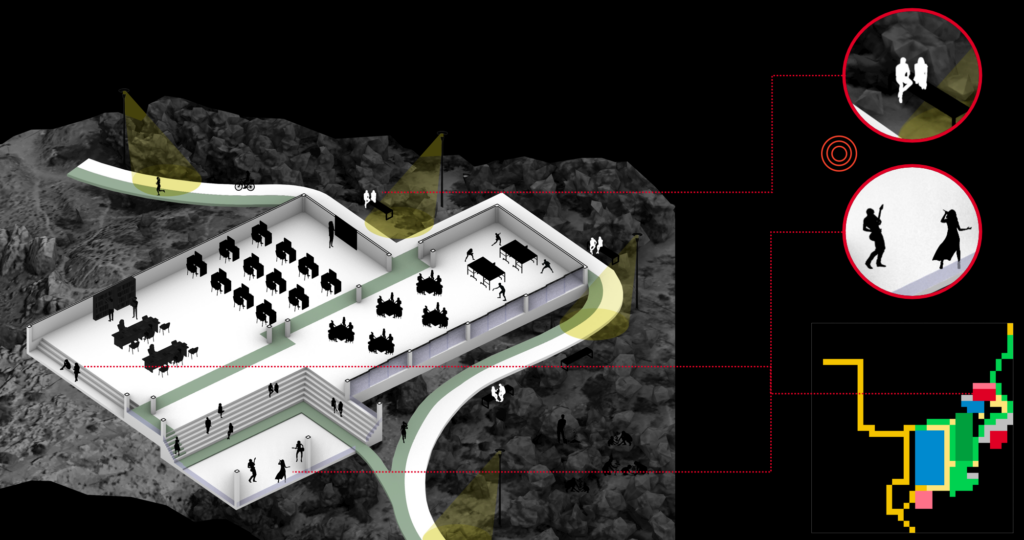

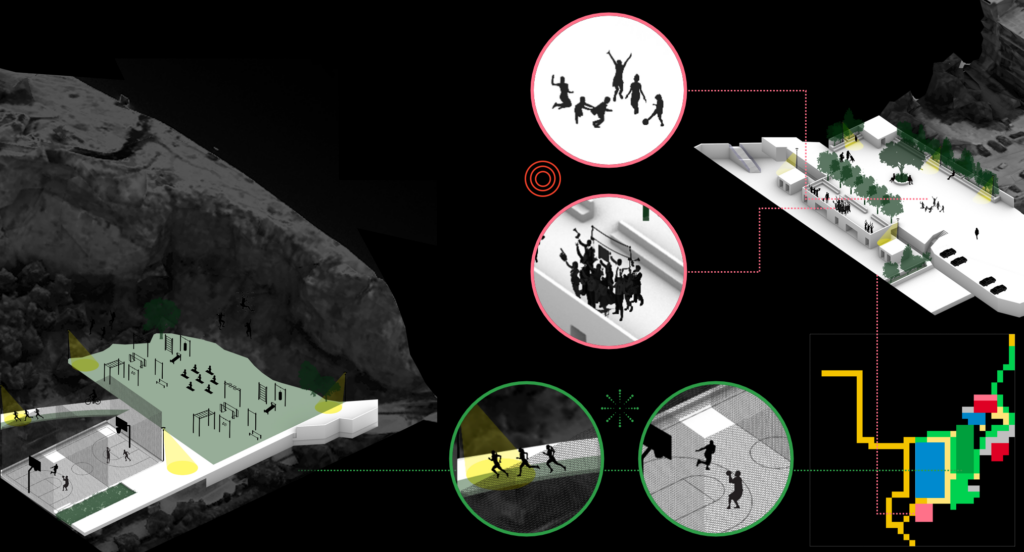

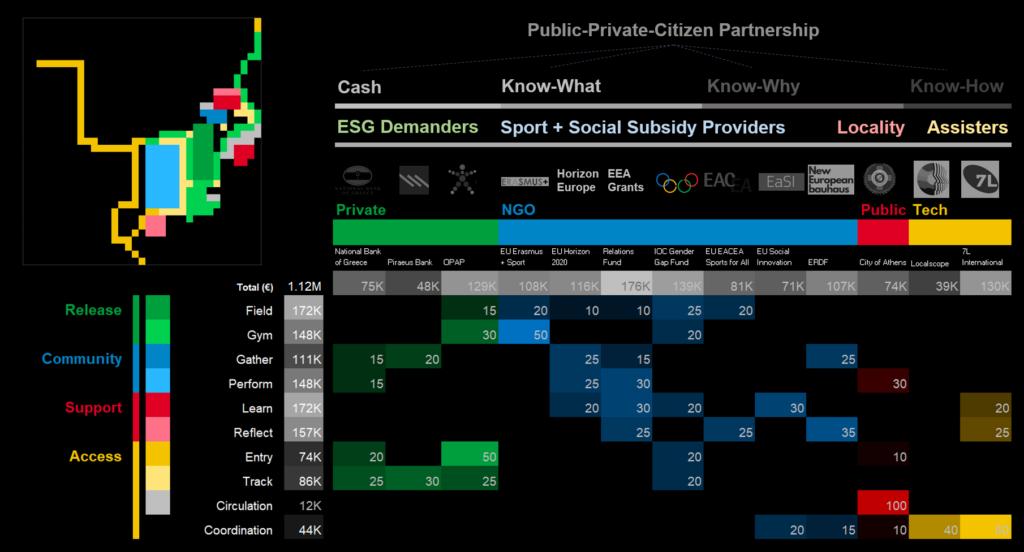

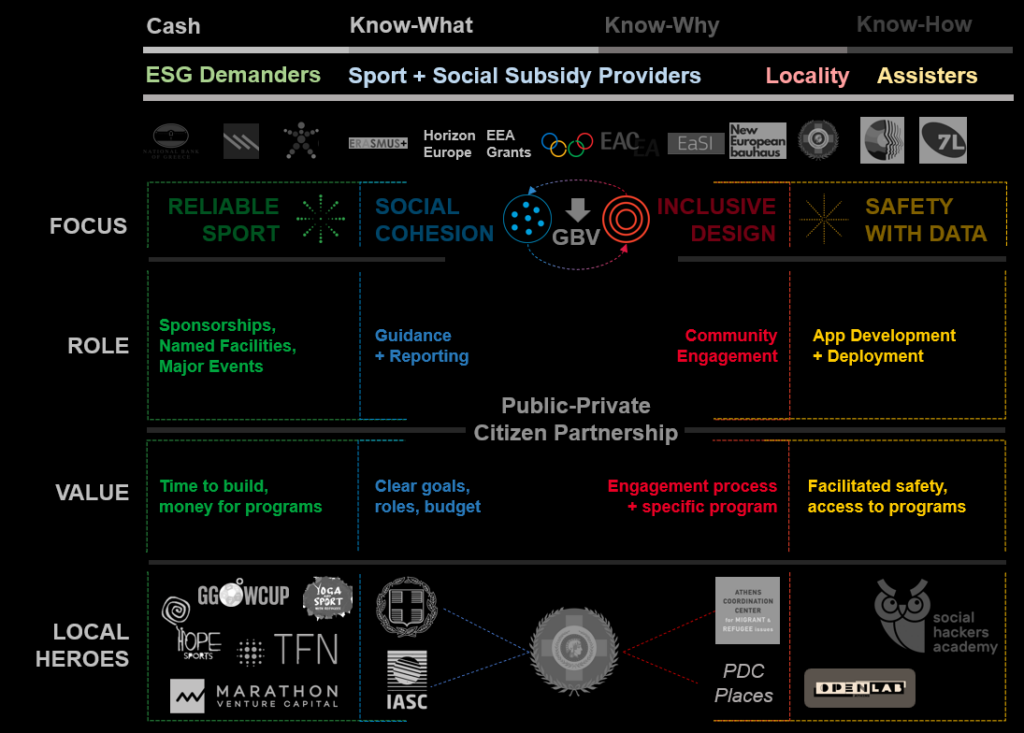

Through the case study of Elikonas Hill in Athens, Greece, justice is modeled at the 10x10m scale to maximize use and minimize cost. Improvements and programs are matched with partners that demand the social goal of the space type: sports, education and mentoring, and cohesion.

The fund’s ongoing mission is to select and catalyze projects in areas susceptible to violence against women at safe, accessible sites with reliable programs that build mechanisms to cope and retain independence.

The role of the fund is narrowed by geography:

- Catalyze | Make funds available for projects and lead multi-scalar partner communication

- Global Benchmarking | Benchmark the intersectional drivers of the rate of gender-based violence

- Continental Coordination | Coordinate inventoried indicators of gender-based violence (European Institute for Gender Equality) with European Union-wide funds for activities that advance equality by gender through the identified social goal.

- National Plans | Plan the path from investigation to funding allocation and creation of selection criteria by geography to support girls at risk of gender-based violence. Align continental funds to key intersectional needs by geography.

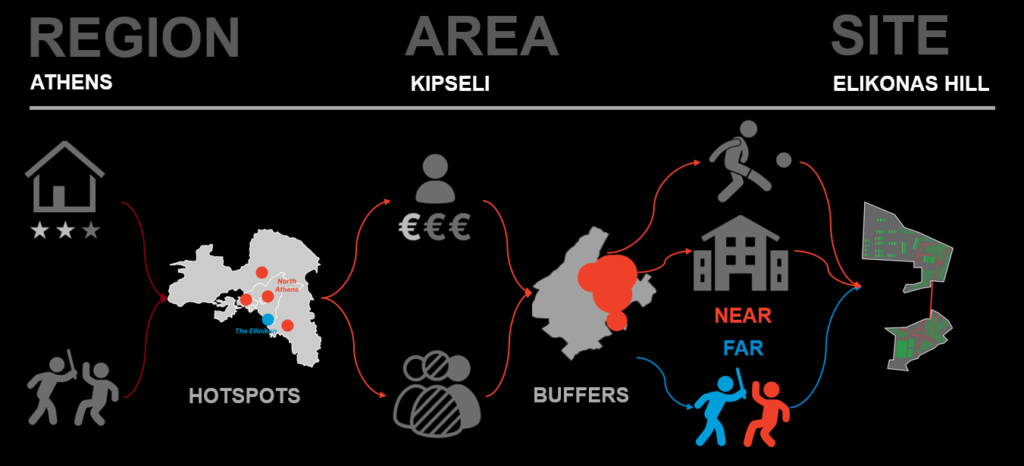

- Regional Prioritization | Prioritize site selection and activities within at-risk neighborhoods but at safe sites, measured by distance from incidents of sexual harassment and by integration, walking distance, and visibility shifts due to site features; here, a steep, sloped site boundary.

- Site Programming | Existing conditions of the site lay the foundation for potential programs. Site improvement opportunities locate partners sponsoring spaces. The needs of the nearest stakeholders by ethnicity, the 1,200 students of the Gravas School, determine the sports, education, and social cohesion programs worthy of sponsorship.

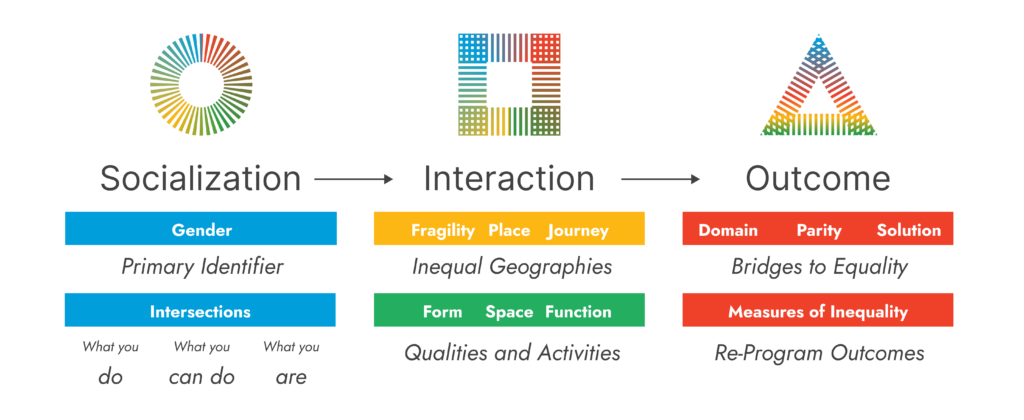

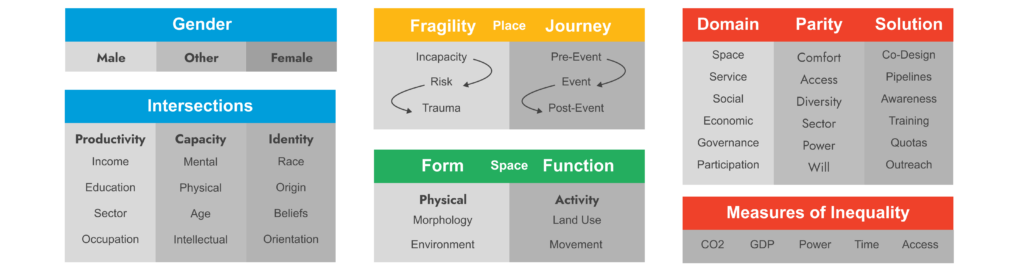

Theory: Outcomes are spatialized by adverse interactions

The project took gendered space as an investigation guided by people, their interactions in space, and resulting outcomes that structure power.

In other words, intersectional socializations are spatialized by experiences throughout places and in spaces that yield unequal outcomes by

- domain, the sphere of power;

- parity, the gradient of power; and

- solutions, the levers to shift power.

A person’s socialization is their identity. Identities are composed of identifiers. The person’s primary identifier, what people are often first recognized by, is their gender. For most people today that is male and female; for some, that includes non-binary and trans people. An intersectional approach considers layers of identifiers of people. People may be identified by their productivity, capacity, or identity group.

A person’s identity is context for other actors in space. This context guides the decision to interact.

- Interaction | Interactions in which an incapacity is exploited and results in an unequal outcome is an event.

- Fragility | When this context is perceived as an incapacity, the fragility of the person is a person is at risk of a traumatic event.

- Journey | Journeys with events can be segmented experience by pre-event, event, and post-event place.

People of different identities prefer and require different conditions of spaces.

- Form | Qualities of space, morphological and environmental, alter the perception of risk and likelihood of an event to occur.

- Function | Activities in space are events: the use of the land and movement through the land.

People are impacted differently by the interactions and qualities of spaces. Their outcomes can be compared by domain and by measure of wealth. Differences in emission of CO2, earnings in GDP, power by status, time in minutes, and acess in meters explain variations in power.

Solutions coordinate the preferences of the powerless. The impact of solutions that bridge to equality is the quantity of shifted power by parity.

In the domain of:

- space, comfort is afforded to the powerless through a co-design process;

- service, access to space is facilitated with pipeline programs;

- society, diversity in people is fostered through awareness programs;

- economy, training programs address gaps across sectors;

- governance, structured gaps in power are bridged with quotas;

- participation, the will to be involved is encouraged through outreach activities.

Layers of identifiers guide the selection criteria for place through mixed-methods filtering. The design structures the improvements that need to be made to improve the outcomes of specific people is grounded in deep research on the challenges and opportunities that encumber places. In this case, we focused on improving the outcomes of recent in-migrant teenage girls in the Kypseli neighborhood of Athens, Greece.

Methodology

The project focuses on locating the selection criteria for a program that acutely impacts a gendered condition in the European context.

Comparative research among European cities is supported by a rich network of data and policy activities that clue into the issues that acutely impact NUTS geographies: countries, regions, and urban areas.

Context: Finding a Gendered Geography

Violence Against Women | Violence against women and girls is rooted in gender inequality and perpetuated by an inequitable balance of power and resources.

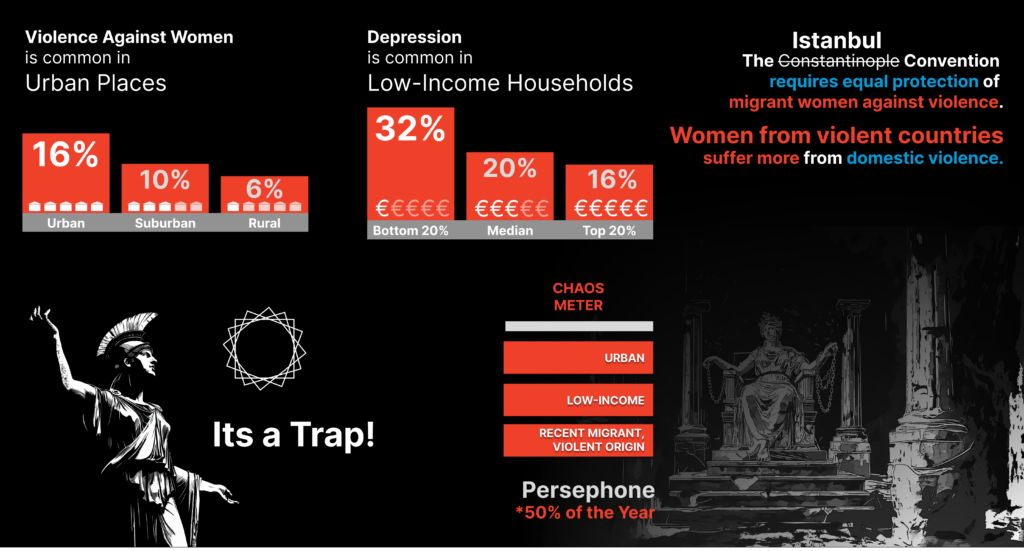

Women who need sport are found to live with turbulence:

- in urban places, with a high density and diversity of people,

- from low-income households, and having

- recently migrated from countries where women believe they deserve violence.

Gender Mainstreaming | Integration of the gender perspective into all other policies

The continental search is guided by the European Union (EU) and United Nations (UN) definitions of gender equality and their resulting efforts. Understanding the EU’s gender equality strategy and focusing on gender mainstreaming efforts funded by URBACT’s Gender-Equal Cities initiative guided the approach to project selection. The European research focused on understanding URBACT’s Gender-Equal Cities efforts as case studies. They revealed that the European Union, European Commission, and their network organize EU funds to support activities for gender mainstreaming. The stages of mainstreaming that receive funding are in discovery through investigation, in education through advocacy, to recognize issues and chart goals through plans, to address experiences through programs, and to require equality by mandating a shift in an unequal practice.

The Olympics and Gender Equality

The Olympics are already working on bridging gender gaps in athlete participation, leadership and coaching, and empowerment. Existing efforts to bridge equality include:

- Equal athlete participation | Paris 2024 is aiming for a historic first: exactly 50% female participation among athletes. Initiatives like the rule change allowing mixed-gender flag bearers at the Opening Ceremony (implemented in Tokyo 2020) aim to increase female athlete visibility. This aligns with SDG 5’s targets of promoting equal access to physical activity and sport for women and girls (SDG 5.1).

- Leadership and coaching | The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has significantly increased female representation in its ranks. As of 2023, women hold 41% of IOC Memberships, which is double the number in 2013. While progress is slower, the IOC is also encouraging National Olympic Committees (NOCs) to include more women in leadership positions which has proven to be more difficult in countries that accept violence against women. The IOC’s push for more women in leadership roles and coaching positions directly addresses SDG 5.5, which seeks to ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in sport.

- Empowerment

- The IOC collaborates with National Olympic Committees (NOCs) to conduct workshops and programs specifically designed to empower girls in sports. These programs can cover topics like leadership training, health education, and overcoming societal barriers that might hinder girls from participating in sports.

- The IOC actively promotes successful female athletes as role models for young girls. By showcasing successful female athletes and promoting gender-balanced sports participation, the Olympics can help challenge traditional gender norms and inspire young girls (SDG 5.1).

The Istanbul Convention

- Enhanced Legal Protection for All Women: The Istanbul Convention ensures equal protection for all women in Athens, regardless of their immigration status. This means migrant women experiencing violence would have the same legal rights and access to support services as Greek citizens.

- In the wake of the convention, Greece plans to improve victim support, provide police and judiciary training, and facilitate collaboration among government agencies and NGOs.

Therefore, the will to support women facing violence, specifically in urban areas, from low-income, recently migrated households is collectively supported by the EU’s comprehensive strategy to bridge gender inequality, Istanbul Convention’s commitment to equal protection of women against gender-based and domestic violence, and IOC’s contribution towards SDG 5 and gender-equal competition.

Context: Finding a Catalyst for Change

A catalyst increases the potential rate of achieving an outcome. In this case, the outcomes are inequalities in sports facilities and in the experience of gender-based violence and the catalyst is the historic gap in funding for men versus women for Olympic Games.

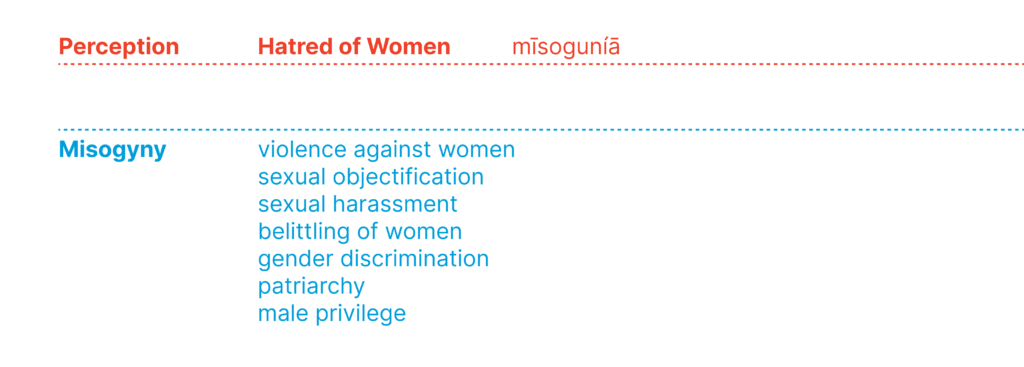

Timeline: Misogyny to Equality

The origin of misogyny in sports is reflected in the intended user of Olympic Games infrastructure.

Misogyny, defined as the hatred of women, is actionized through violence, objectification, harassment, belittling, discrimination, structure power, and privilege.

- 776 BC | The First Ancient Olympics

- Perception: The Ancient Greeks perceived women as incapable of participating in or even watching sports. Women were viewed strictly as caretakers of the home and family, not athletes. The myth of Pandora was commonly referenced, painting women as bearers of misfortune and weakness.

- Misogyny: Violence: Violence against women refers to any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life.

- Discrimination: Women were strictly prohibited from participating in the Olympics. Attendance by married women even as spectators, was punishable by death.

- 1896 | The First Modern Olympics

- Perception: The revival of the Olympics under Pierre de Coubertin’s leadership still reflected traditional views that sport was an endeavor for men, emphasizing masculine virtues of competition and physical strength.

- Misogyny: Discrimination: Discrimination against women refers to any distinction, exclusion, or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment, or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil, or any other field.

- Discrimination: Women were not allowed to compete in the first modern Olympics. Pierre de Coubertin famously said that the inclusion of women would be “impractical, uninteresting, unaesthetic, and incorrect.”

- 1900 | The First Olympics with Female Competitors

- Perception: There was a slight shift in perception as society began to accept the idea of women participating in sports, though mainly in what were considered “ladylike” competitions.

- Misogyny: Patriarchy: Patriarchy is a social system in which men hold primary power and predominate in roles of political leadership, moral authority, social privilege, and control of property. It also involves the subordination of women through various structures and practices.

- Discrimination: Only 22 women, out of a total of 997 athletes, competed in the 1900 Paris Olympics in sports like tennis and golf. They faced significant societal pushback and media criticism. Few attended their competitions and no competition venues held explicitly female events.

- 2024 | The First Olympics with Gender-Equality in Competitors

- Perception: The perception of women in sports has dramatically changed, with a strong emphasis on capability and equality. Women are seen as equally capable as men in athleticism and competitiveness.

- Misogyny: Privilege: Privilege in this context refers to the special rights, advantages, or immunities granted or available only to a particular person or group of people—in this case, men over women.

- Discrimination: While the number of male and female competitors is equal, there remain issues such as unequal media coverage and sponsorship, as well as disparities in coaching and administrative positions in sports organizations.

- 2048 | The First Olympics with Gender-Equality in Infrastructure

- Perception: The society of 2048 views sports as entirely gender-neutral, focusing on the prowess and achievements of athletes regardless of gender. There is a strong institutional and cultural support system that values and promotes diversity in sports.

- Equality: Equality in sports infrastructure means providing equal opportunities and resources for all athletes, regardless of gender. This includes equitable funding, access to training facilities, quality of coaching, medical care, and promotion.

- Discrimination: This future Olympics is envisioned to have no discrimination where equal opportunity, funding, media exposure, medical support, and facilities are provided to all athletes regardless of gender. This also extends to equal pay for coaches, regardless of the gender of the teams they coach.

- The impact of misogyny on sports infrastructure through the lens of the Olympics is reflected today by:

- Violence: harassment by coaches, unequal safety measures in training, or ignoring complaints from female athletes.

- Discrimination: allocation of resources, such as funding or training facilities, or in media representation and wage disparities.

- Patriarchy: male-dominated leadership and decision-making bodies, which may prioritize male sports programs and overlook or underfund women’s sports initiatives.

- Privilege: endorsements, better training times, and more significant media attention, all examples of privilege that reinforce gender disparities in sports.

- Equality: In sports infrastructure, achieving equality means that facilities, funding, coaching, medical care, and media coverage are distributed fairly and equitably, ensuring that female athletes have the same opportunities as male athletes to succeed and excel.

- This gap is calculated by cross-multiplying the participation gap and funding for each Olympics since 1896, then multiplied by 0.71, the average budget allocation for sports facilities. (International Olympic Committee).

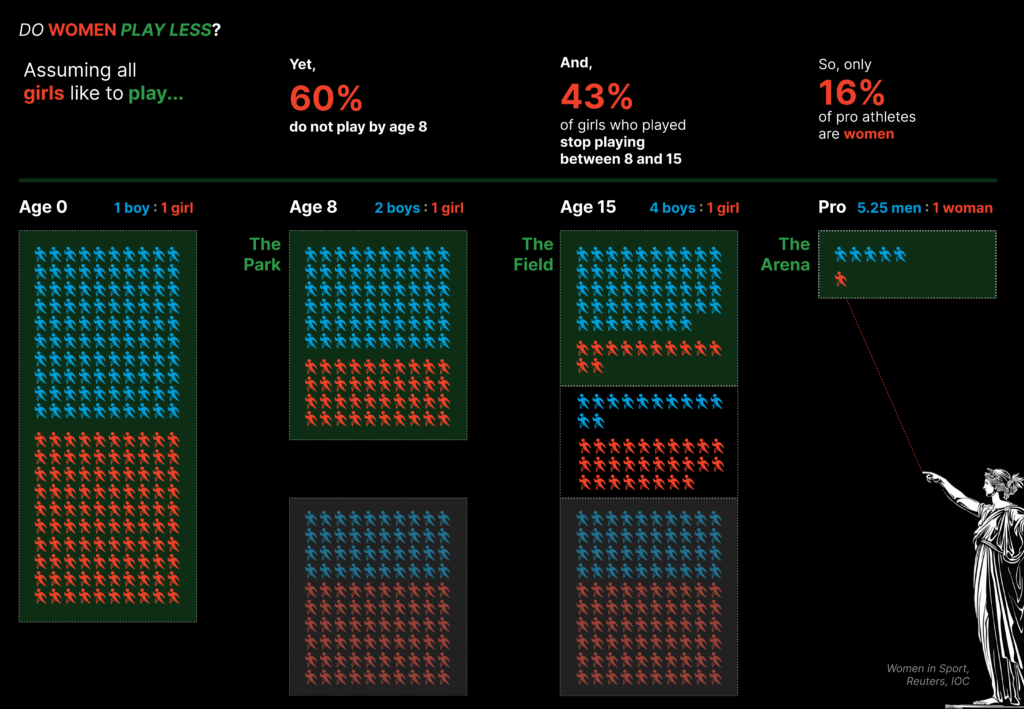

Benchmarking: Need for Sports Facilities for Teen Girls

A series of questions and answers led to the key impediments to the pro-athlete gender gap.

- Charting by age, do women play less?

- Yes, assuming 100% of women like to play.

- By age 8, there are two boys for every girl in parks.

- By age 15, there are four boys for every girl on sports fields. 43% of girls who played and reportedly enjoyed sport at 8 drop out of sport at 15.

- So, only 16% of professional athletes are women.

- Why do women play less?

- Quantity of Space | Sports divide space among genders.

- What is the gap in Olympic sports facilities for men and women?

- What is the gap in youth facilities for boys and girls?

- Quality of Space | Women prefer different sports spaces than men.

- Unsafe training environments: Without safe, supportive environments, the risks can outweigh the benefits of participation, leading women to abandon sports either temporarily or permanently.

- Violence | Women leave sports due to the impact of violence on mental health.

- Women face violence from their coaches, at home, and in public spaces. In Europe, women face violence most acutely from age 15 to 19.

- Of surveyed girls who left sports due to mental health conditions between 8 and 15,

- 61% experienced anxiety,

- 50% experienced doubt,

- 45% experienced eating disorders,

- 41% were overwhelmed by work or study,

- 38% fear the outside.

- Quantity of Space | Sports divide space among genders.

The gender sports infrastructure gap, present from playgrounds to arenas, is identified as the source of the 43% loss in girls who play sports at eight and do not play by 15, translating to a 5.25:1 ratio of male to female professional athletes.

Analysis: Developing Selection Criteria

Selecting a Context

The Gender-Equal Olympics in the European context to address violence against women.

Needs of people

Source: Urban Perceptions Survey

- The Urban Perceptions Survey, part of the Flash Eurobarometer 419 on Quality of Life in European Cities 2015, focuses on evaluating various aspects of urban living in European cities, including Athens. The survey covers numerous domains such as public services, environmental conditions, personal safety, and overall satisfaction with city life. For a detailed analysis, I divided the survey into three key themes: vibe, spaces, and acceptance.

- Spaces examine the quality and accessibility of public infrastructure, including transport, health services, and green spaces. “

- Acceptance investigates the integration and perception of foreigners within the community.

- Vibe encompasses general satisfaction with living in the city, feelings of safety, and trust in fellow citizens.

- Findings specific to Athens reveal significant challenges and areas for improvement.

- The overall satisfaction in Greater Athens has increased by 15% since the last survey, yet it remains relatively low at 71%.

- Public transport satisfaction is notably low, with only 45% expressing contentment. Safety concerns are prominent, with 63% in Greater Athens and 62% in Athens feeling unsafe.

- Dissatisfaction extends to cleanliness and the availability of green spaces, where Athens ranks among the lowest.

- The acceptance and integration of foreigners is a significant challenge for Greater Athens.

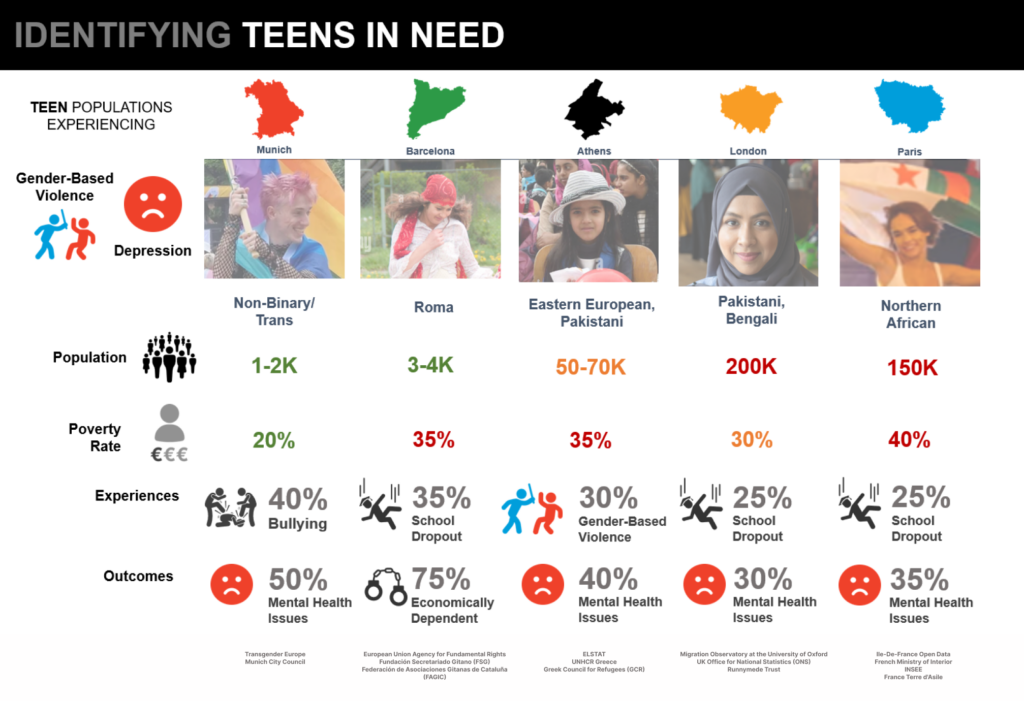

At-Risk Population Analysis

Qualitatively, we reviewed city-wide reports on vulnerable populations to center on intersections in need of recreation infrastructure.

Source: Eurostat, OECD, Eurobarometer, Transgender Europe, Munich City Council, European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Fundación Secretariado Gitano (FSG), Federación de Asociaciones Gitanas de Cataluña (FAGIC), ELSTAT, UNHCR Greece, Greek Council for Refugees (GCR), Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) Runnymede Trust, Ile-De-France Open Data, French Ministry of Interior, INSEE, France Terre d’Asile

Teen populations experiencing gender-based violence were identified from city reports on at-risk people in each post-Olympic city. The population count, poverty rate, discriminatory experiences, and the outcomes of these experiences, we will use data from national statistical offices, Eurostat, and OECD. Population counts and poverty rates will be sourced from these institutions, ensuring we have the most recent and standardized data. Rates of discriminatory experiences are located from Eurobarometer results and commentary on foreign acceptance. The outcomes of these experiences—mental health, physical health, economic status, and educational attainment—were collected from health surveys, education statistics, labor market reports, and academic studies to connect experiences to outcomes. Correlation analysis will help identify the relationships between discriminatory experiences and outcomes in mental health, physical health, economic status, and education. Comparative analysis will highlight patterns and discrepancies across the cities. This approach allows us to contextualize findings within each city’s socio-economic and cultural environment, considering historical, political, and economic influences.

In all cities, poverty level trends with school dropouts. The smallest analyzed group, non-binary and trans people in Munich, are small in number but experience the highest rate of mental health issues.

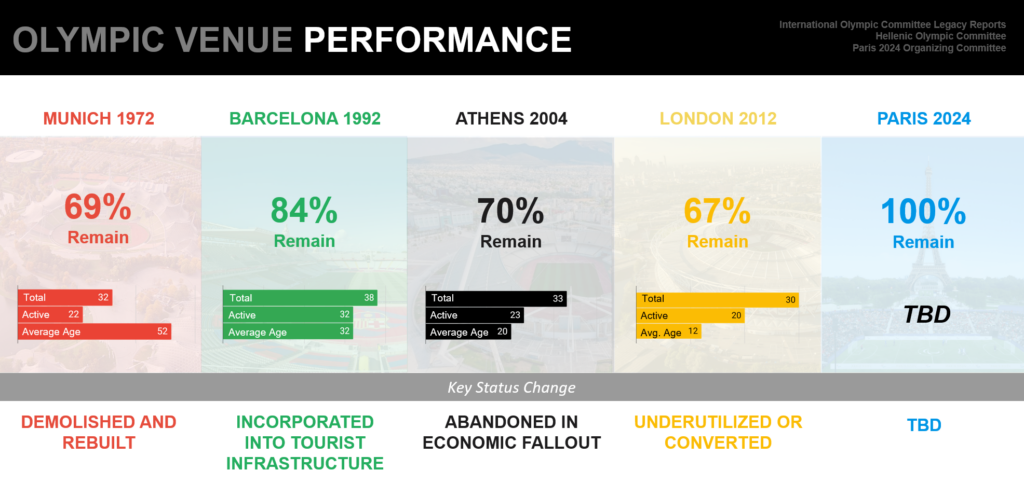

Value of Olympic infrastructure

Current Venue Status

Identifying the use of 153 Olympic venues for European hosting cities (1972 – 2024).

- Temporary vs. Permanent: Understand the intended permanence of the stadium. Many Olympic facilities are temporary. Temporary facilities popularized as the IOC shifted their development strategy to reduce the impact of the Olympics on the host city.

- Active vs. Inactive: Determine the operational status of each stadium.

- Age Analysis: Calculate the age of each stadium from the year built.

- Renovation History: Review renovation dates and costs to assess upkeep.

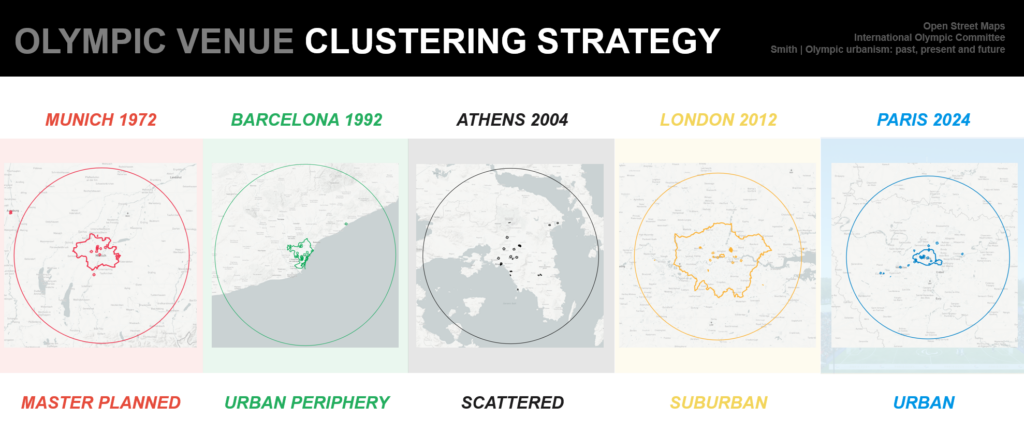

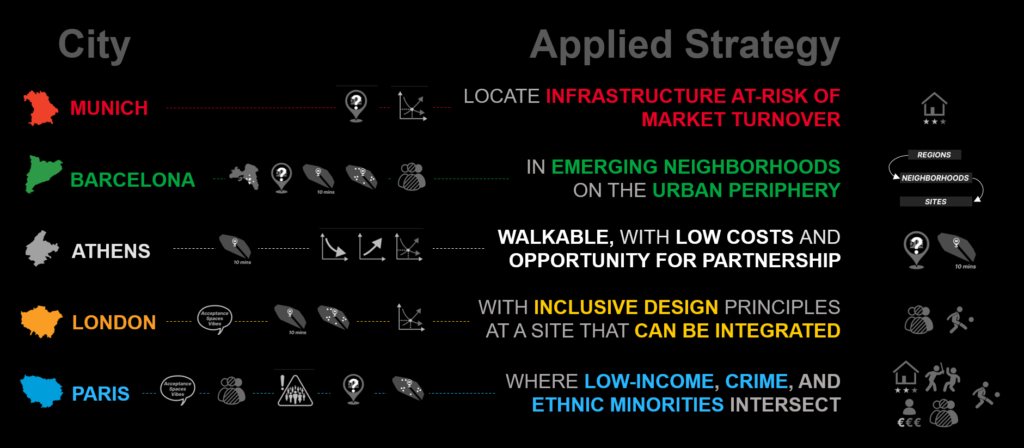

Clustering Strategy

Understanding the theory behind the placement of new Olympic stadiums.

Sources |

- Munich | A masterplanned Olympic clustering strategy involves the intentional design and development of sports facilities and related infrastructure within a defined area, typically a central park just outside of the inner ring.

- Munich’s Olympic Park is the central node of the masterplanned sports cluster. Located on the urban periphery, the park was designed as a comprehensive complex that includes the Olympic Stadium, Olympic Hall, and Olympic Village.

- Key Features: Centralized location of venues, integrated transportation systems (e.g., U-Bahn extensions), and extensive green spaces. The masterplanning facilitated ease of movement for athletes and spectators, creating a lasting legacy as a recreational and event space for the city.

- Barcelona | Barcelona’s Olympic strategy focused on revitalizing and developing the urban periphery. The Olympic Village and facilities were built along the coast, transforming previously underutilized areas and improving connectivity between the city center and peripheral neighborhoods, leading to long-term urban renewal. The focus on revitalizing and cohesively developing the Montjuïc area and at the western edges of the city removed the possibility for stadiums to interrupt the urban flow.

- Athens | Athens aimed to spread the trappings of Olympic infrastructure by scattering stadiums throughout urban and dense suburban areas of the city. Stadiums are largely underutilized and as many as nine have fallen into disrepair since 2004.

- Athens’ stadiums suffered from the fallout of the Greek economy.

- For women: The decentralized Olympic facilities in Athens led to inconsistent improvements in women’s access to services and safety across different parts of the city.

- London | London’s suburban Olympic development promoted economic regeneration in suburban areas, potentially increasing employment opportunities for women and improving suburban infrastructure. That said, the placement of facilities in low-density areas has contributed to their underuse.

- Paris |.Paris has two key priorities: social cohesion through new sports infrastructure and the clean up of the Seine in central Paris. The joint effort intends to alleviate historic conflict among high-income populations in the center and low-income populations in the banlieues.

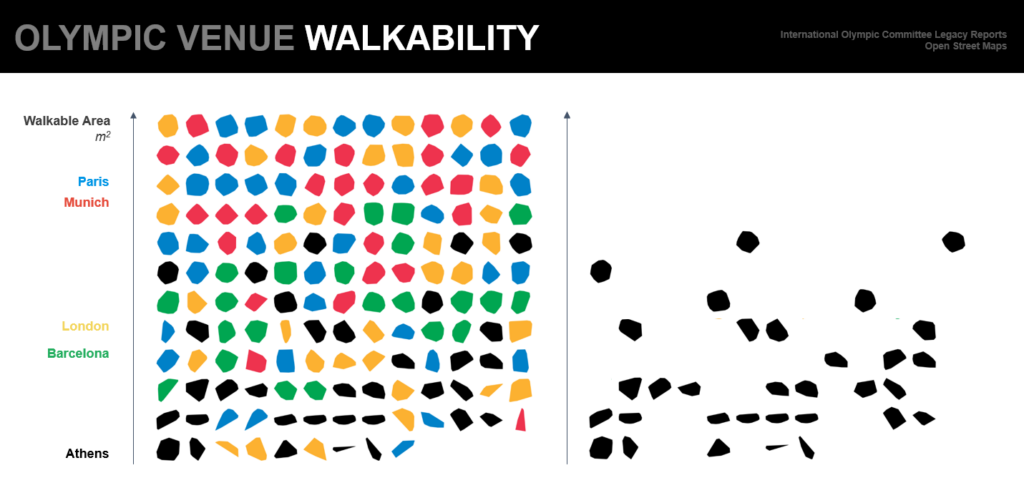

Walkability

Olympic venues were compared by their walkable surrounding area. For each venue, a walking graph was generated from OpenStreetMap data using osmnx within a 2000-meter radius, defining the scope for accessibility by foot. The calculate_isochrone function then computed the maximum walking distance based on a 15-minute walk at 4.8 km/h, used this to extract a subgraph of reachable nodes, and formed a convex hull from these nodes to visualize the walkable area as an isochrone polygon.

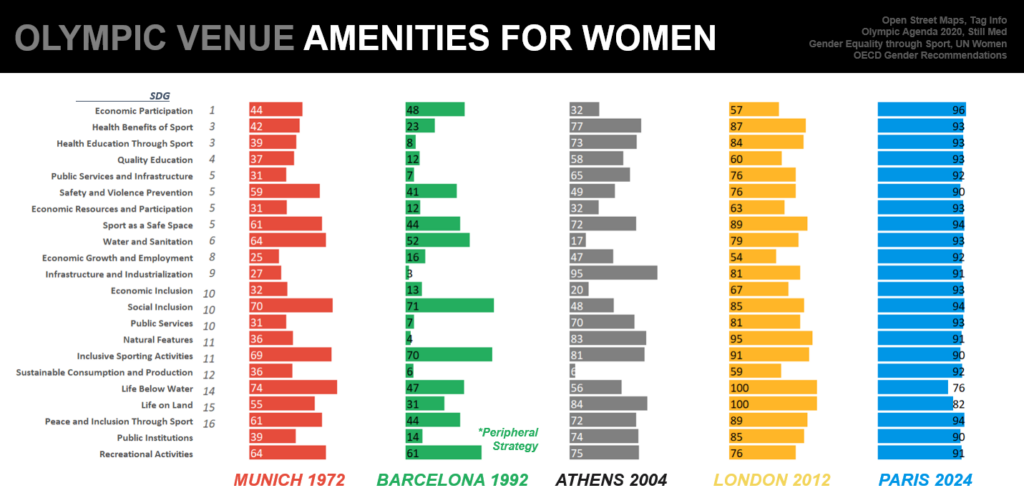

Amenities near Olympic Facilities

In the local context, buildings use, amenities and transportation network were evaluated within a 10 min walk isochrome for all the venues tagged by their relevance to SDG 5 and cross-cutting initiatives.

- To understand if sports facilities serve women’s needs, the amenities supportive of Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG 5), were tabulated by their cross-cutting initiative. To assign amenities, each cross-cut’s relevant amenities were inventoried in a dictionary of relevant OpenStreetMaps tags.

- The isochrone serves as the boundary of relevant features. The features were average across facilities and normalized on a scale from 0 to 100. Facilities of interest, those in neighborhoods with the target population, were analyzed for their provision of amenities.

- A key finding is that the quantity of amenities for women is not indicative of the commercial or gender-based success of the stadium. For example, Barcelona’s stadiums have performed the best in terms of active status and maintenance yet have the least amenities due to the city’s placement of Olympic stadiums on the urban periphery.

Appetite for new sports facilities

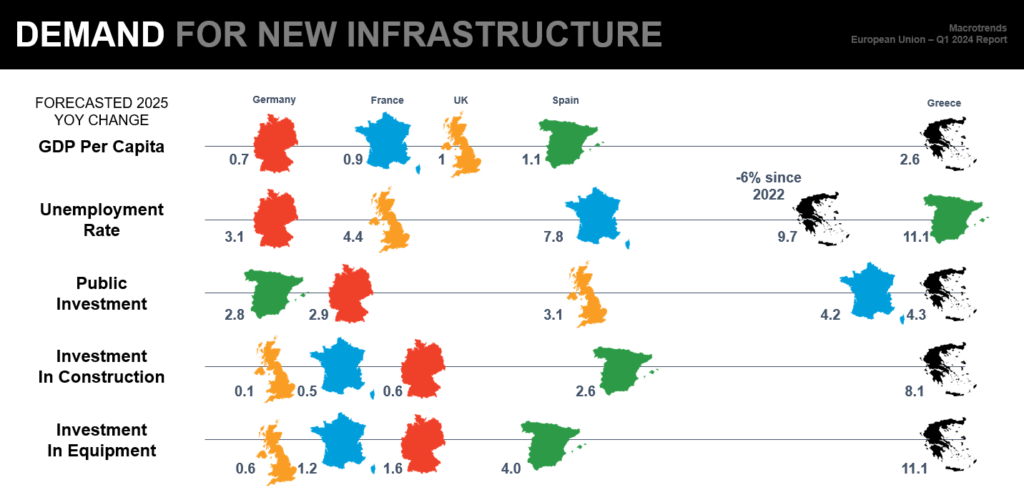

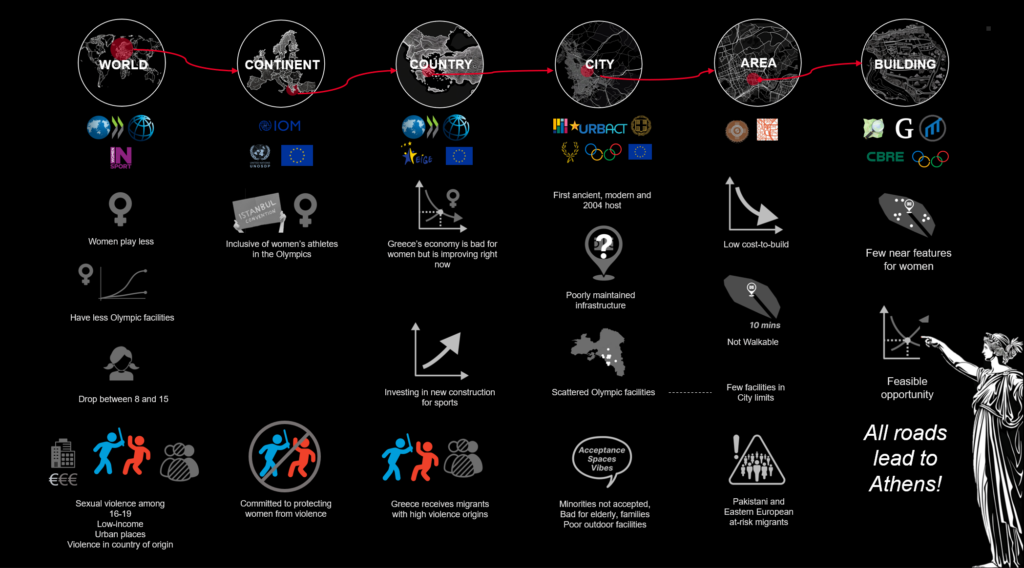

Macroeconomic trends for construction and investment appetite revealed Greece to be the best candidate for new youth sports facilities.

Greece’s economic outlook for new sports infrastructure is particularly positive due to several factors. The anticipated 2.2% GDP growth in 2024 is underpinned by substantial public and private investment in construction, driven by the Recovery and Resilience Plan. This plan allocates significant resources for developing new sports facilities. The projected increase in construction investment to 6.7% in 2024 highlights a strong demand for new infrastructure. Moreover, rising real disposable incomes and decreasing unemployment rates will likely boost public engagement in sports, creating a compelling need for modern and accessible sports facilities across the country.

We reviewed the current conditions of five stadiums in target neighborhoods for opportunities to reprogram their use.

Selecting Athens by Navigating Multiple Scales

City Selection | Understanding Olympic strategies and performance to best select sites for funded improvements

- Needs of People:

- Greece receives a high density of migrants from countries that accept violence against women. Migrant women are proven to be at heightened risk of violence.

- Analyze demographic data to understand population demographics, including age groups and interests in sports and recreation.

- Sports Infrastructure:

- Assess existing sports facilities, including their condition, capacity, and accessibility.

- Evaluate plans for future sports infrastructure developments and their alignment with community needs.

- Market Dynamics:

- Conduct market analysis to understand trends in sports participation and recreational activities within the city.

- Evaluate economic factors such as funding availability, sponsorship opportunities, and public-private partnerships for sports infrastructure projects.

What are programs?

What are outcomes?

Socio-Economic Project Selection Criteria

With the ocean of information available in the European continent, spatial conditions, and existing programs to network. The project began understanding continental challenges, specifically those related to gender-based violence by scale, income, and ethnicity. We understood the Istanbul Convention’s requirement to protect women from gender-based violence regardless of their ethnicity and resulting national plans to be key drivers of change and rationale to meet social goals.

We found that gender-based violence is most common in urban places, against women, by someone close to the victim, in households with low-income, and among recent in-migrants from violent origins. We also found surveys to be unhelpful in comparison because the perceptions of “violence is okay” varies by place. Europe’s first round of surveys to understand gender-based challenges through a survey was a failure due to the lack of granularity of the results. This, therefore, could not be the mechanism to select a place. What is missing and what this project intends to identify are the infrastructural and hotspot conditions for presence of violence against women.

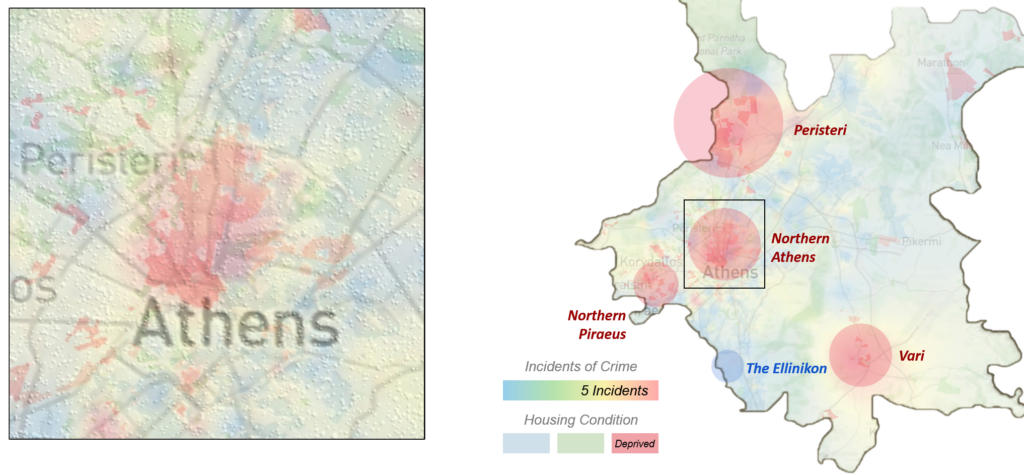

Neighborhood Selection | The Kypseli neighborhood, City of Athens: home to many migrants, low-income households, and crime.

- Density of Deprived Housing: Use census and socio-economic data to identify neighborhoods with higher concentrations of deprived housing.

- Crime Hotspots: Generate heatmaps to identify neighborhoods with higher incidences of crime.

- Ethnicities from Violent Origins (OECD): Connect migration database statistics to survey responses asking women if violence against women is okay.

- Prioritize areas where the overall density of sports facilities is lacking.

Site Selection:

- Hotspots of Play:

- Map areas with high recreational activity, including parks, playgrounds, and informal sports venues.

- Identify opportunities to enhance existing facilities or establish new ones based on community usage patterns.

- Detractors of Sexual Harassment Incidents:

- Review reported incidents and community feedback regarding safety concerns, particularly related to sexual harassment.

- Implement design and security measures to create safe and inclusive environments for all users.

- Spatial Conditions:

- Conduct site surveys to assess terrain, accessibility, and environmental suitability for sports facility development.

- Consider proximity to public transportation, parking availability, and potential for expansion or future enhancements.

- Access:

- Evaluate the site’s accessibility for diverse user groups, including people with disabilities and elderly individuals.

- Ensure connectivity to surrounding neighborhoods and amenities to promote active transportation and community integration.

Site analysis

A site analysis was performed to propose design solutions that would fit the context and the current programming of the site. The analysis revealed several challenges and opportunities that affected the use of the site by teen girls:

- A space syntax network analysis revealed that the site is out of the way, making it less likely to be utilized by teen girls.

- A light and visibility analysis showed that the site is poorly lit compared to the surrounding area and is not visible from the surrounding areas. These factors contribute to a feeling of unsafety and make the site less attractive.

- A spatial-topographical analysis revealed that the site is difficult to access due to a lack of entrances, and has poor connectivity to the nearest bus stop.

- An analysis of the current programs on-site showed that these programs were not designed with the needs of teenage girls in mind, with most programs being tailored for boys.

Design solutions

To address the challenges and opportunities identified in the city and site analyses, we propose two connected approaches to encourage teen girls to practice more sports:

Program

The population in this case was better understood through understanding the likelihood of violence among ethnicities through their origin country’s determination of if violence is okay, the sports that different genders enjoy, the hero of Olympic sport in their origin country and sectoral education and employment opportunities. Understanding these factors for Eastern European and Middle Eastern populations in the Kypseli neighborhood helped select a program relevant to their needs.

The programs are based on the typical practices of the population served by the project.

Increasing Access:

- Sports Facilities Enhancement:

- Recommendation: Expand and diversify sports facilities to cater to a wider range of activities and interests.

- Case Study Finding: Avondale Park in London increased access by offering a multi-use sports field, basketball courts, a skatepark, and outdoor fitness equipment, accommodating various sports and recreational activities for teenagers.

- Programming Diversity:

- Recommendation: Introduce diverse programming that includes organized leagues, tournaments, and skill development clinics.

- Case Study Finding: The St. Anne’s Teen Sports Park in Dublin offers flexible programming such as drop-in sessions and community tournaments, encouraging consistent engagement and skill enhancement among teenagers.

Spaces of Release (Sport):

- Physical Activity Promotion:

- Recommendation: Promote physical activity through accessible and well-maintained sports facilities.

- Case Study Finding: Hackney Marshes in London provides over 80 football pitches, ensuring ample space for sports and physical exercise, which contributes to improved physical health and well-being among users.

- Health and Well-being Initiatives:

- Recommendation: Incorporate outdoor fitness equipment and spaces for activities like yoga and calisthenics.

- Case Study Finding: Oakwood Teen Sports Park in Seattle integrates outdoor fitness equipment and skateboarding ramps, offering opportunities for diverse physical activities and promoting overall health.

Spaces of Support (Discussion, Education):

- Educational Workshops:

- Recommendation: Organize workshops on topics like sportsmanship, health education, and career guidance.

- Case Study Finding: The Roundhouse Community Arts & Recreation Centre in Vancouver hosts educational workshops alongside sports activities, fostering holistic development and life skills among participants.

- Youth Leadership Programs:

- Recommendation: Establish youth leadership programs involving mentoring and skills development.

- Case Study Finding: The Community Sports Hub in Manchester engages teenagers in leadership roles, empowering them to take ownership and initiative in community activities and sports programs.

Spaces of Community (Gathering and Performance):

- Community Events:

- Recommendation: Host community events such as festivals, tournaments, and cultural celebrations.

- Case Study Finding: Avondale Park in London serves as a venue for community events, enhancing social cohesion and community pride through shared experiences and celebrations.

- Performance Spaces:

- Recommendation: Designate spaces for artistic performances, cultural events, and talent showcases.

- Case Study Finding: The Sport Ireland National Indoor Arena in Dublin includes spaces for artistic and cultural performances, promoting cultural diversity and community engagement alongside sports activities.

Key Takeaways from Case Studies:

- Integration of Diverse Activities: Successful community sports sites integrate a variety of sports and recreational activities to appeal to different interests and age groups.

- Community Engagement: Involving the community in the planning and design process fosters ownership and ensures the site meets local needs.

- Inclusive Design: Incorporating accessibility features and promoting inclusivity through diverse programming enhances participation and community cohesion.

Site Redesign and New Programming

The redesign and new programming for the site focus on making the spaces more accessible and safe while also creating new areas where teens can interact. This includes:

- New Safe and Accessible Bike Paths: Proposing well-planned bike paths to improve accessibility.

- Improved Lighting: Enhancing the lighting to ensure the site is well-lit and feels safe.

- Redesigned Common Spaces: Redesigning common areas to encourage interaction among teens.

- New Sport Facilities: Building sports facilities specifically designed for teen girls.

- Supporting Facilities: Adding facilities to support these interventions and ensure their success.

Virtually Connecting to the Site | A rideshare integrated system, and an app complete with rides functionality, program sign-up interface, and social network of local players.

- To ensure that the new site remains utilized, an on-demand integrated transport system for teenage girls in Athens was proposed. This transport system has two distinct elements: the bus stops and the app.

- Bus Stops: The bus stops are designed to be safe spaces for teenage girls. These stops allow for secure entry via the app and also feature a panic button that can be pressed in case of emergency. Their positions and transport routes were calculated with consideration of the most vulnerable neighborhoods.

- On-Demand Transport App: Artemis

- The Artemis app was designed with three main functionalities in mind: Rides, Programs, and Social.

- Rides | The core feature of this approach is to provide safe transport for teens from bus stops to the locations where they want to practice sports, and then from those locations back to their homes. Teens can also view if other teens are waiting for the bus, enhancing safety and encouraging social interaction.

- Programs | This functionality allows teenage girls to sign up for different programs offered on-site. Users can browse through available activities, such as basketball, soccer, yoga, or swimming, and register for their preferred programs directly through the app. This ensures easy access to organized sports and activities, encouraging consistent participation.

- Friends | This feature allows teens to add friends within the app and see which of their friends are using the site and when. It was designed to increase interaction between teens, fostering a supportive community and enhancing the overall experience.

Financing

The financing was calculated by program within each 10×10 meter square of the site.

- The granularity of the assumptions organized the scale of the research.

- The global research revealed that the UN, OECD, and World Bank are able to collectively reduce risk by partnering with public entities and the European Union on innovative projects. The larger the project, the greater the number of seats at the table.

- The LOMIGRAS Project revealed that the public should not take the lead in ensuring the success of the project as their leadership has hindered migrant outcomes. Instead, a subsidiary of the city, PDC Places and the Athens Coordination Center, may serve as experts on migrant needs and integration challenges, led by the requirements of the IASC and Hellenic

The site work within squares consists of hard costs, equipment, and ongoing costs. The strategy relies on eliminating barriers and implementing new points of access.

Buy a Space

Invest in physical sports infrastructure, including community fields, gyms, and stadiums, to foster sports participation and enhance community engagement.

- Benefits:

- Asset Appreciation: Potential for significant long-term growth due to rising demand for sports venues.

- Revenue Generation: Opportunities through facility rentals and hosting events.

- Branding Opportunities: Visibility through naming rights and signage.

- Risks:

- Capital Intensive: High initial investment and maintenance costs.

- Market Fluctuations: Susceptible to changes in community interest and economic downturns.

- Optimal Candidates:

- Real Estate Investors: Looking for long-term asset growth.

- Corporate Sponsors: Seeking branding and community engagement opportunities.

Buy a Program

Fund the development and management of sports programs, including training sessions, camps, and clinics, enhancing athletic skills and community health.

- Benefits:

- Community Impact: Direct engagement with community sports participation.

- Scalability: Ability to expand and replicate programs across multiple locations.

- Partnership Opportunities: Collaborations with local businesses and sports teams.

- Risks:

- Operational Challenges: Requires ongoing management and effective marketing.

- Dependence on Participation: Financial viability reliant on sustained community interest.

- Optimal Candidates:

- Sport and Social Subsidy Providers: Focused on social cohesion and equal opportunities among genders.

- Philanthropic Investors: Focused on community development and health.

- Sports Organizations: Looking to expand their outreach and impact.

Impact

Sources

Context and Data

- European Institute for Gender Equality

- The European Commission

- Eurostat

- The European Union Q1 Macrotrends

- The International Olympic Committee

- European Institute for Gender Equality

- Open Street Maps

- TagInfo

- Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP)

Financing

- The Olympic Movement

- The World Bank

- OECD

- UNOSDP

- Monarch Capital

- Horizon Europe 2020-2025

- New European Bauhaus

- Erasmus+

- The European Regional Development Fund

- IRTS

- Interact+

- EaSI

- National Bank of Greece

- Piraeus Bank

- EEA Bilateral Relations Fund

- European Integration Fund

Organizations

- Baldwin-Edwards, M. (2005). The integration of immigrants in Athens: Developing indicators and statistical measures (Pre-final version). Mediterranean Migration Observatory, UEHR, Panteion University.

- Greece: Migrants have limited access to local social services, study finds

- LOMIGRAS report on the role of local government in migrant integration in Europe and Greece

- UNESCO Tackling Violence Against Women and Girls in Sport