Introduction: Understanding Besòs Beyond the Surface

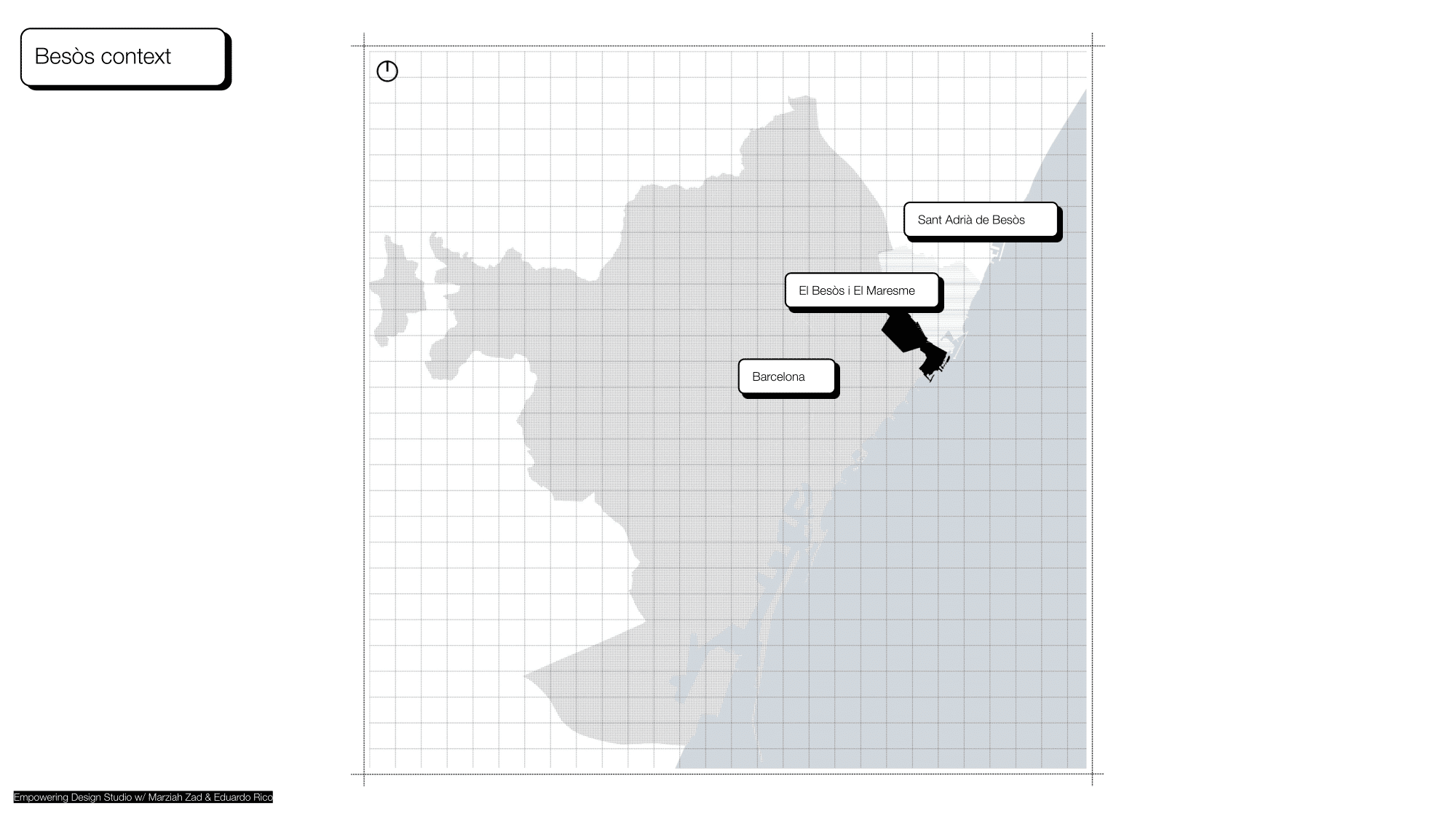

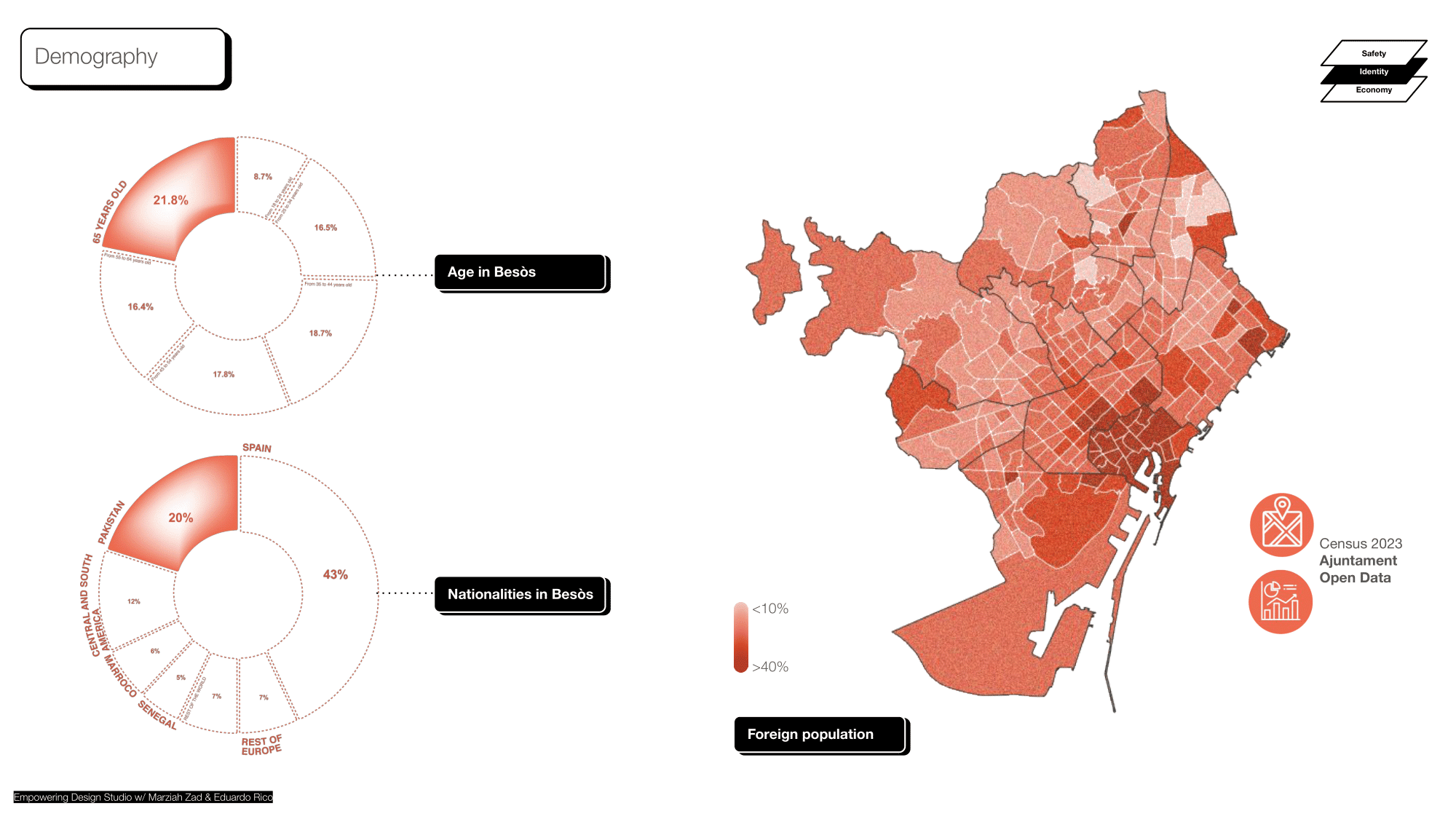

The El Besòs i el Maresme area in Barcelona carries a complex history—one shaped by migration, exclusion, and resilience. Often perceived through the lenses of insecurity and economic struggle, the neighborhood is in fact a vibrant intersection of identities, cultures, and urban transformations. Layers of Besòs is a research-driven project that dives into the multiple narratives that shape this district, questioning how design, participation, and AI-driven insights can contribute to a more inclusive and empowering urban experience.

Context: The Pressures Shaping Besòs

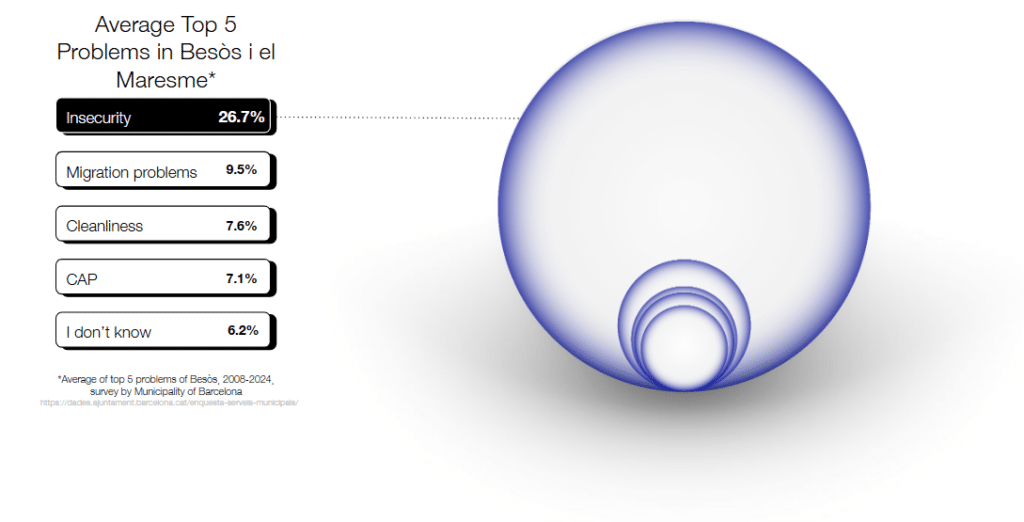

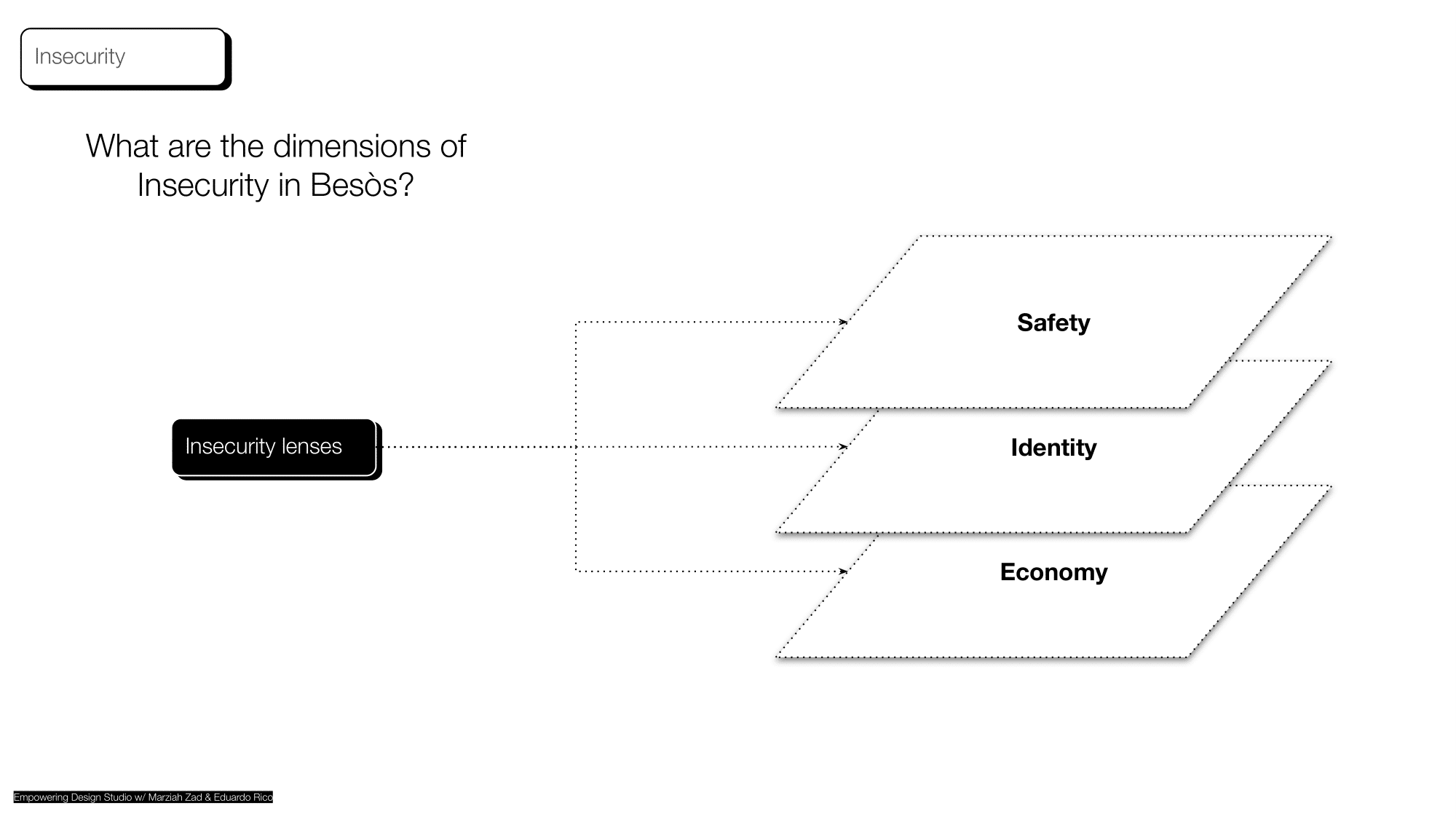

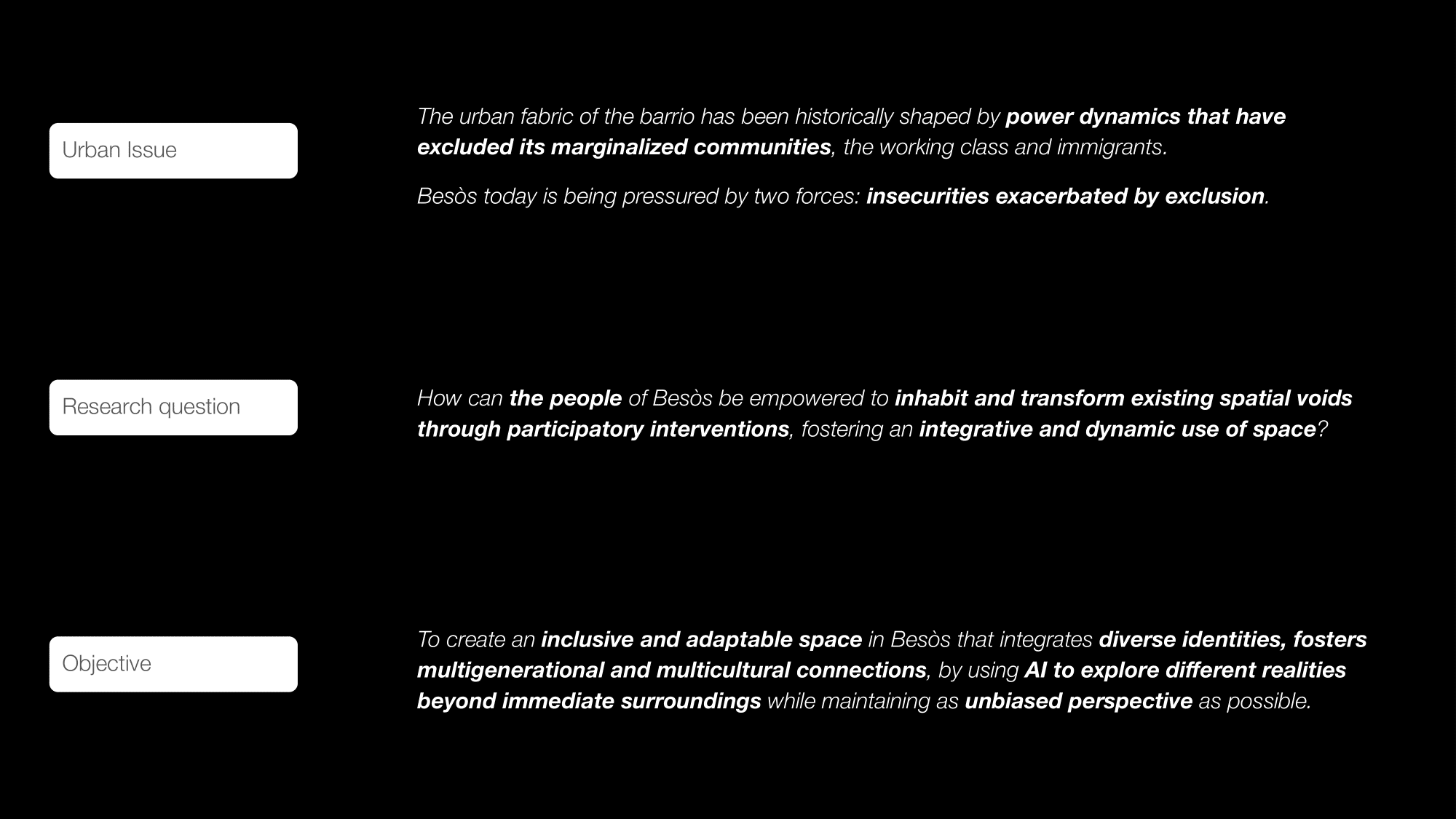

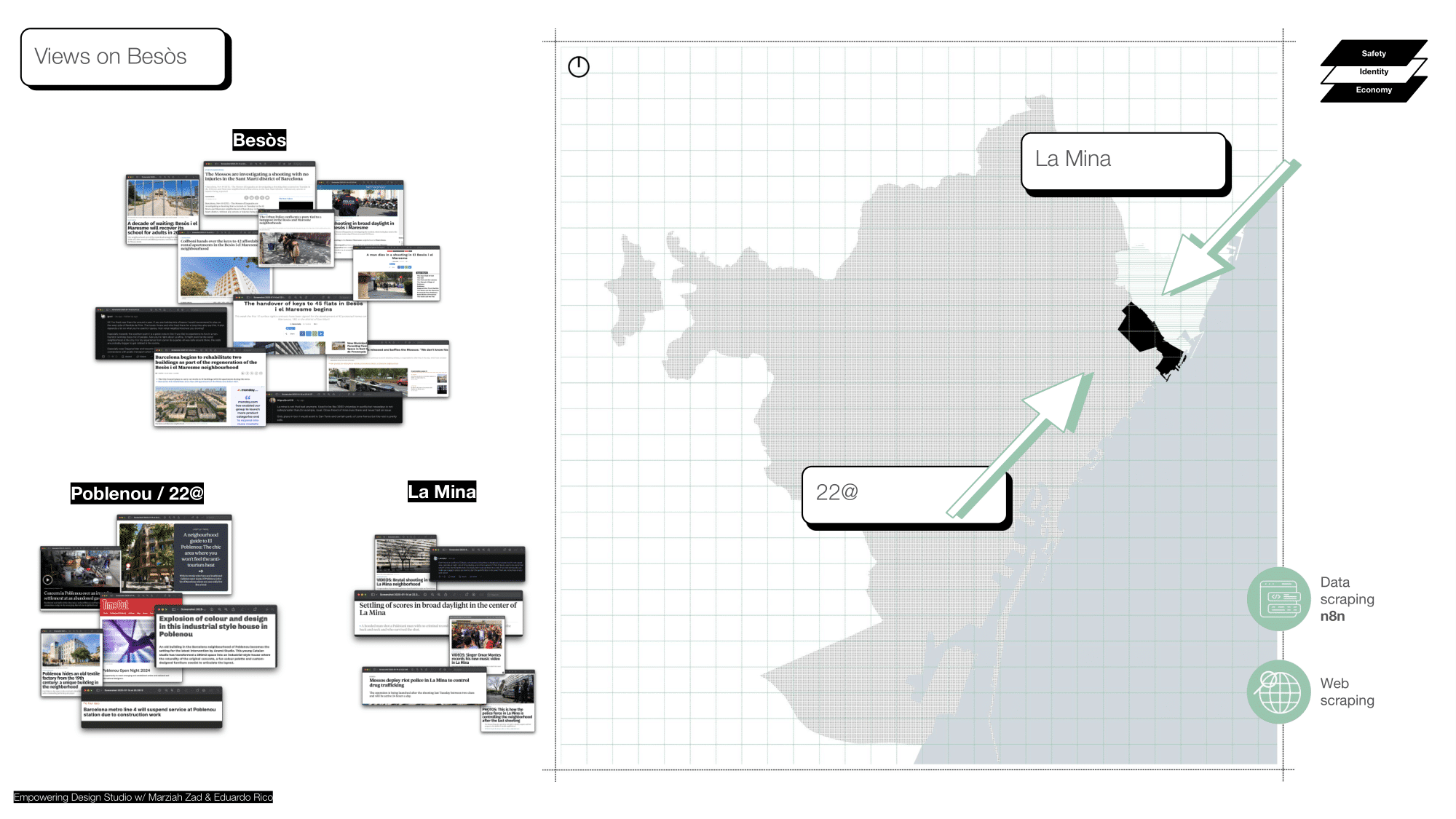

Besòs is historically a working-class and immigrant-dense area, positioned between two contrasting forces—gentrification and systemic neglect. Our research identified that the primary challenge people of Besòs face is “insecurity” – a broad and complex term we decided to unfold further. The first impressions and insights we got from investigating the area hace led us to taking a closer look at three layers of insecurity, that seemed the most relevant for the neighbourhood. We took a closer look at:

- Safety concerns driven by perceptions of insecurity, particularly around certain zones like La Mina.

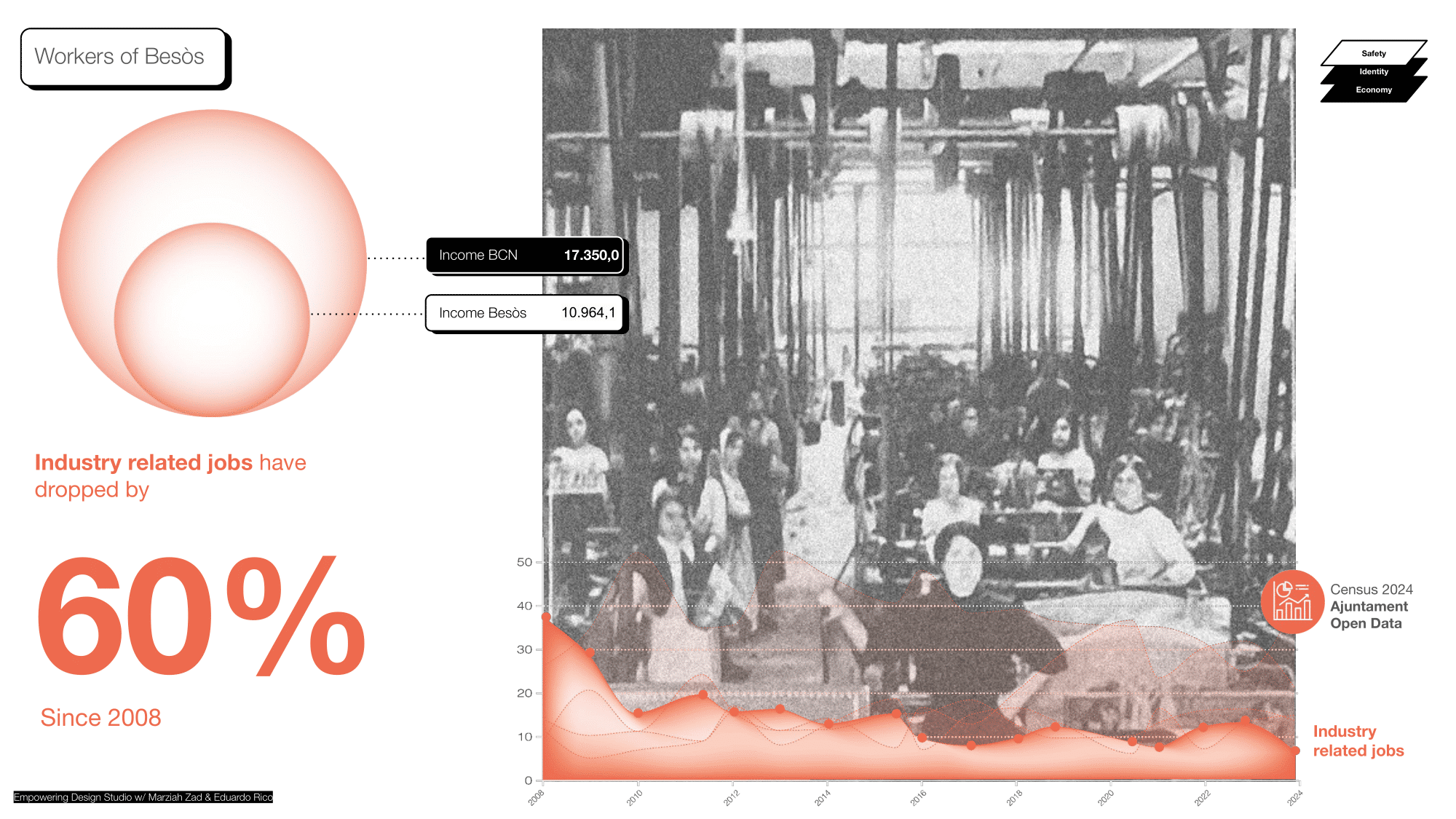

- Economic struggles due to the decline of industrial jobs in the area, leading to increased vulnerability.

- Social exclusion rooted ine historical marginalization, affecting identity and community participation.

By acknowledging these dynamics, Layers of Besòs seeks to move beyond narratives of scarcity and instead focus on opportunities for transformation.

Besòs remains one of Barcelona’s most socioeconomically vulnerable areas, shaped by industrial decline, migration, and spatial segregation. Residents earn 40% less than the city average (Census 2024), a disparity worsened by the 60% loss of industrial jobs since 2008 and the gentrification of neighboring Poblenou. The transition to a knowledge-based economy has left many in low-wage, unstable service jobs, further economic precarity.

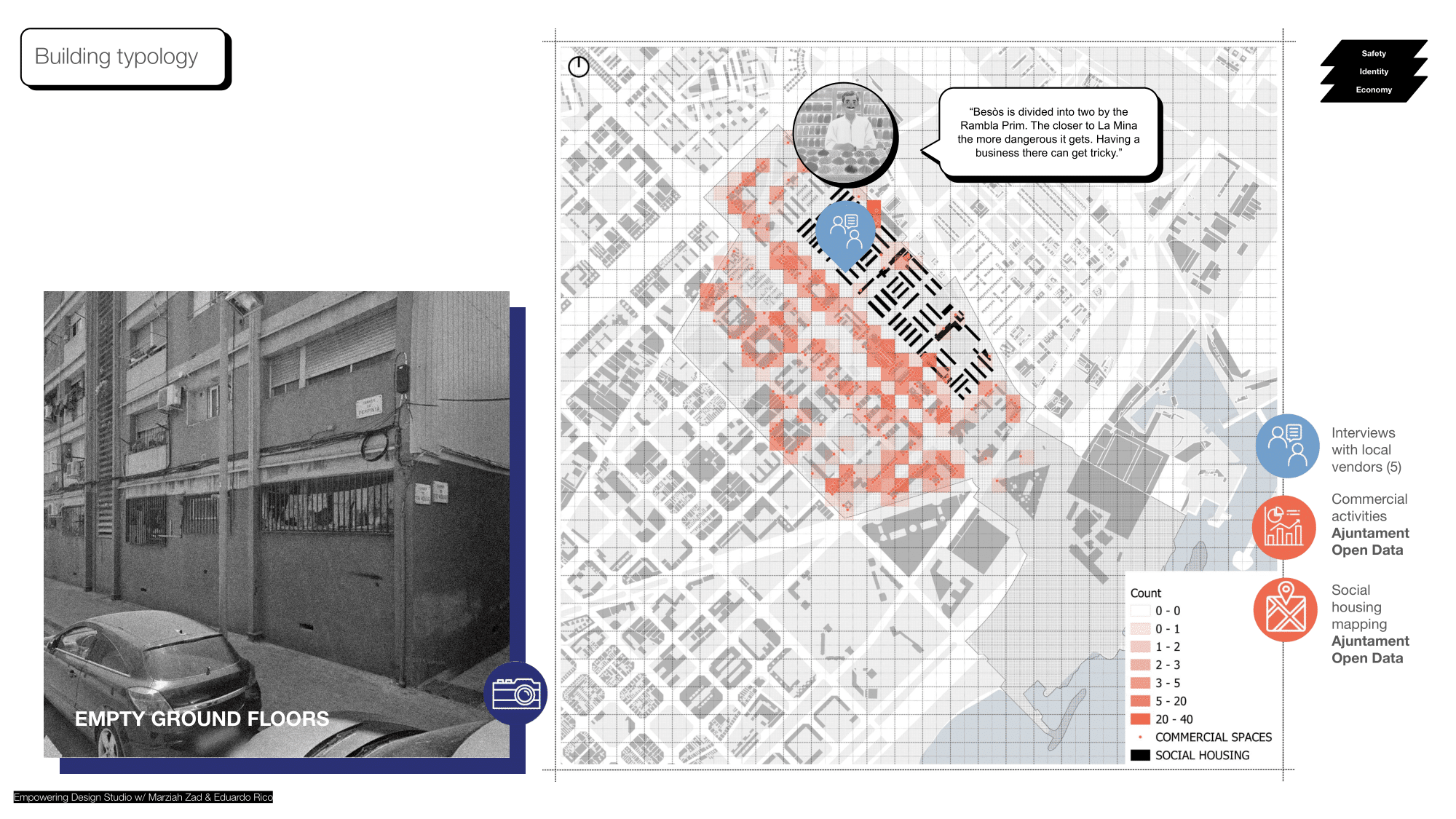

Beyond income disparity, Besòs is physically and socially isolated due to disconnected infrastructure and inactive ground floors in social housing. Insecurity consistently ranks as the area’s top concern (Municipal surveys 2008–2024), deterring investment and reinforcing exclusion. The lack of economic opportunities and vibrant public spaces deepens the cycle of marginalization.

Layers of insecurities: Lenses to data analytics

We acknowledge that insecurity is very complex to define. Although the survey had insecurity as the main issue, it did not provide context on what was meant by it. For this reason, we decided to analyze the situation and develop some insights around it. As a result, in Besòs, we identified three main types of insecurity: Safety, Identity, and Economic. These aspects will be discussed in more detail later in the document, with an explanation of how they affect and can be seen in the neighborhood.

Project objectives

Acknowledging the context of Besòs, we were able to identify and focus on a specific urban issue, come up with a research question as well as create project’s final objective.

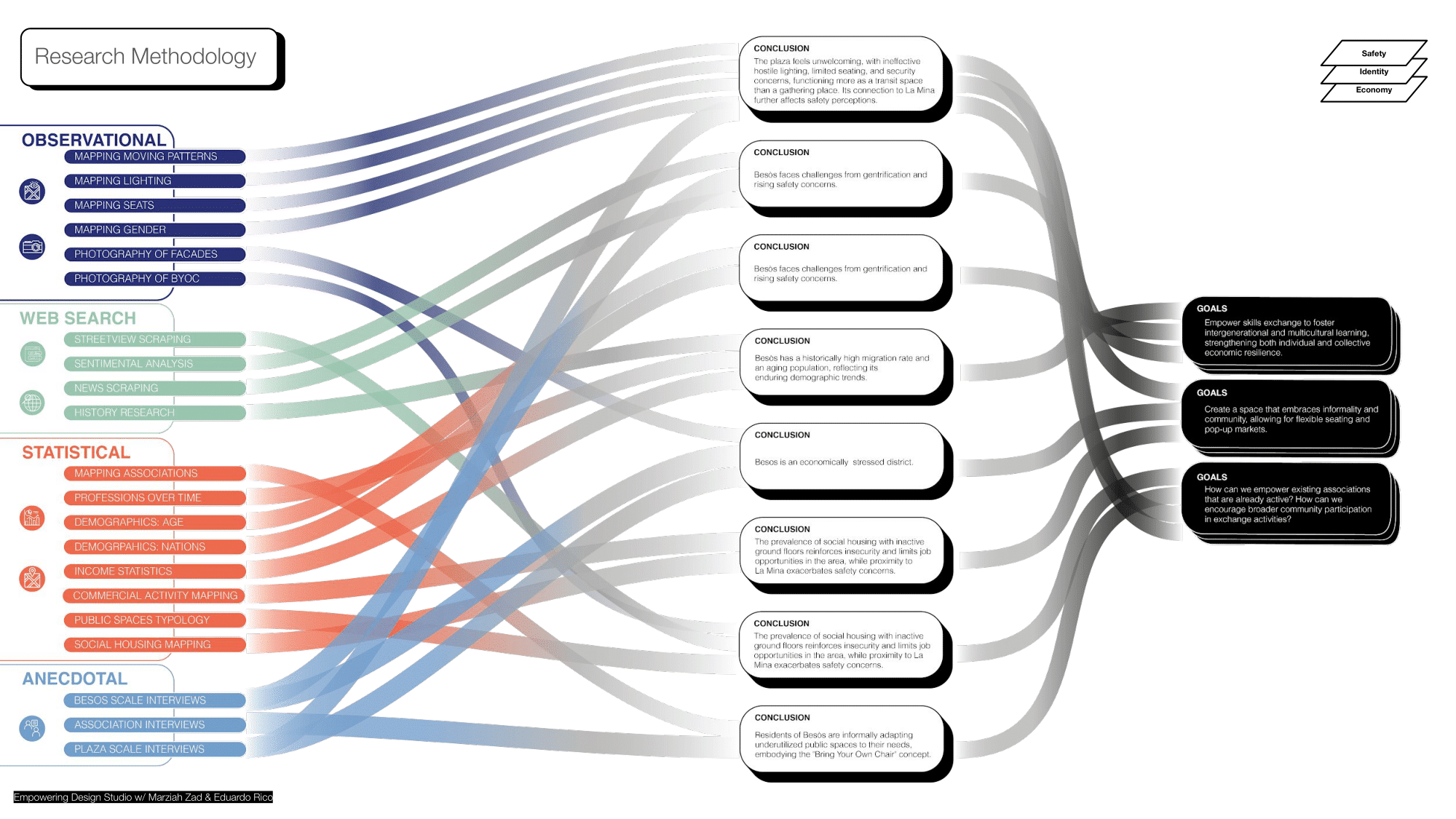

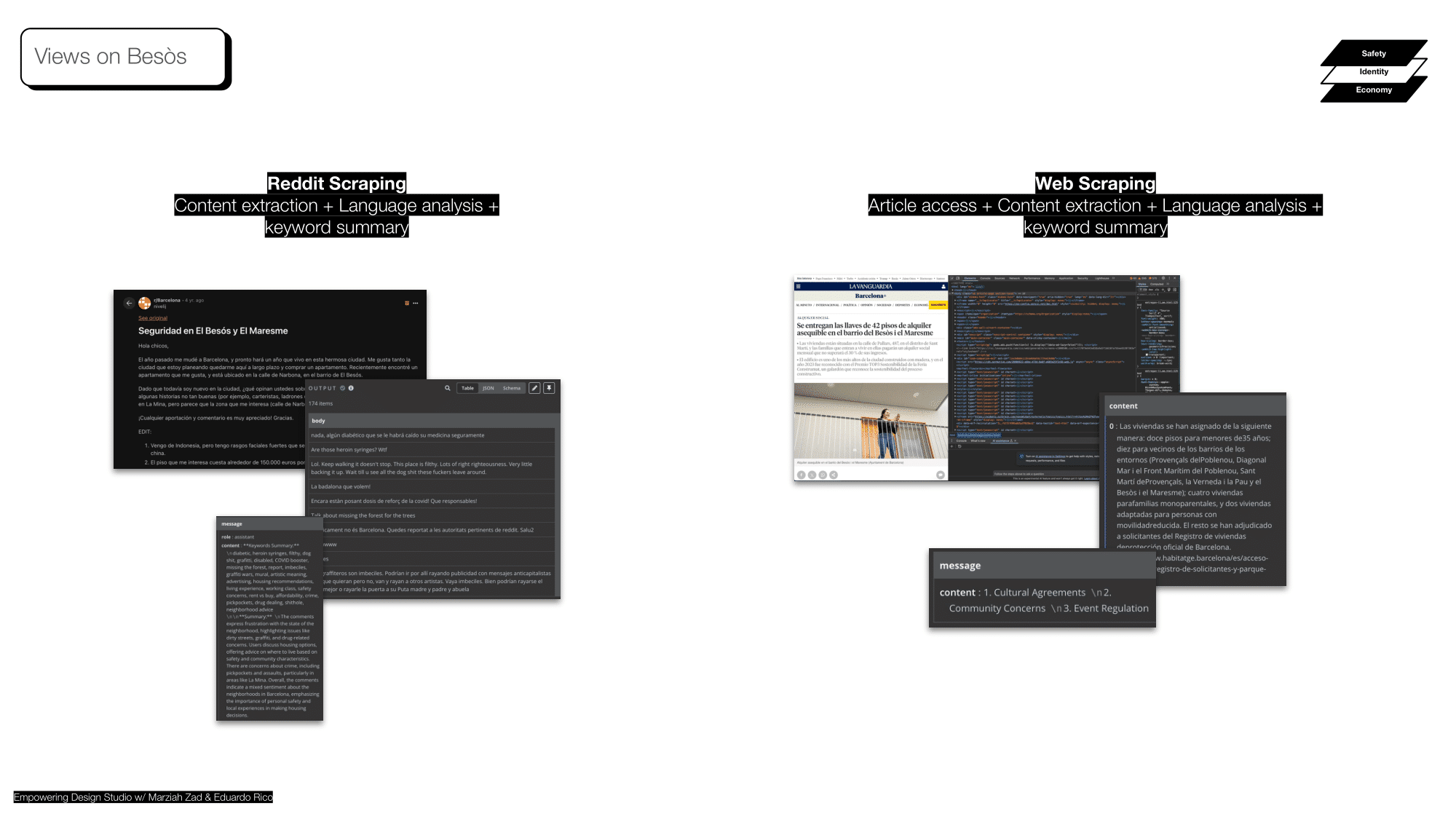

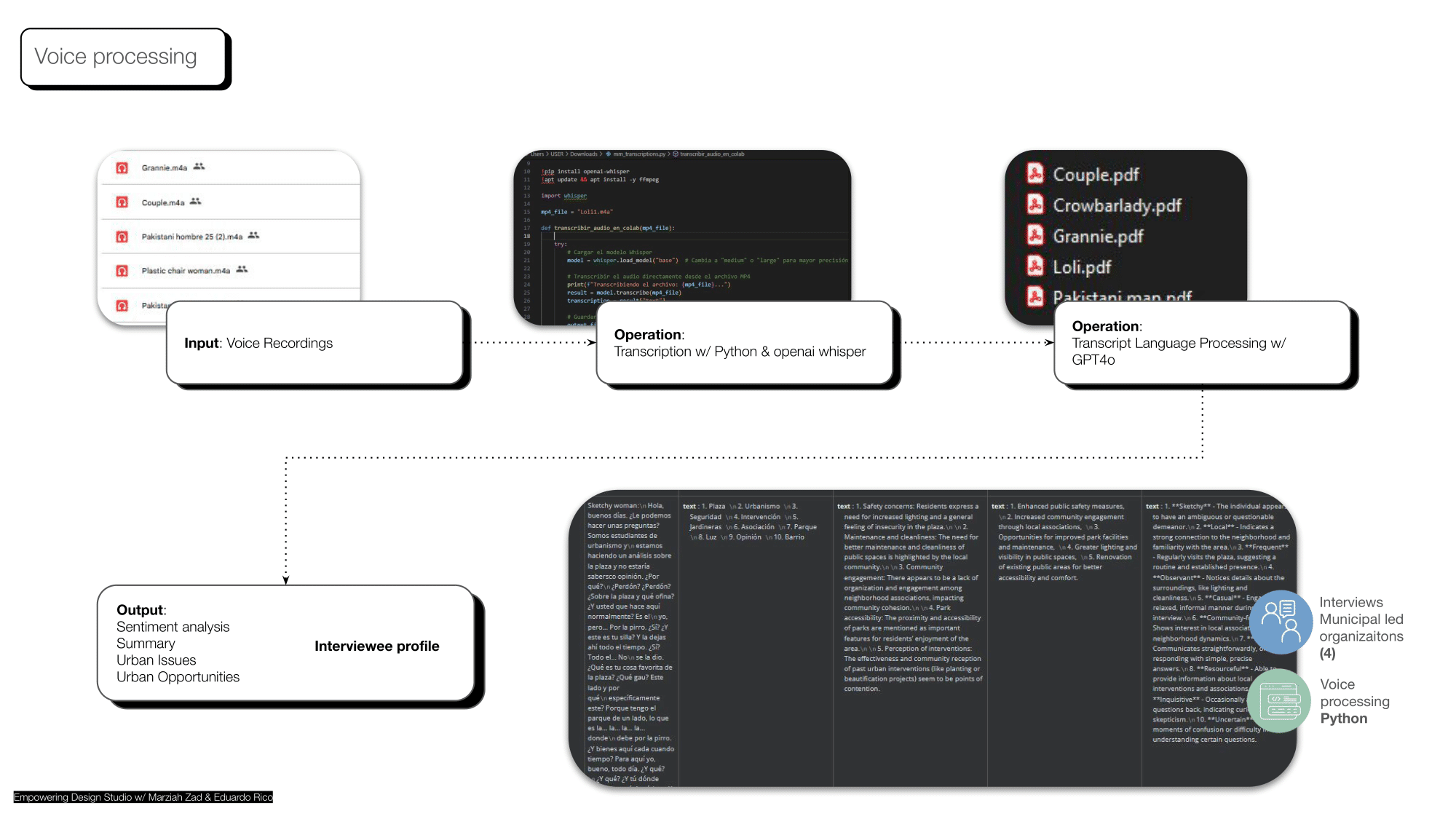

Research Methodology: A Data-Driven Approach to Urban Identity

Our study employed a broad range of data collection techniques to understand the realities of Besòs. We were able to collect observational, web-based, statistical and anectodal data types, which we overlayed together in different compositions which allowed us to understand the area from multiple perspective as well as come up with conclusions and project’s final goals.

Data Analysis

Conclusion 1:

Besòs is being pressured and shaped by two forces: gentrification and unsafety.

Conclusion 2:

History of Besòs is alive through the elderly.

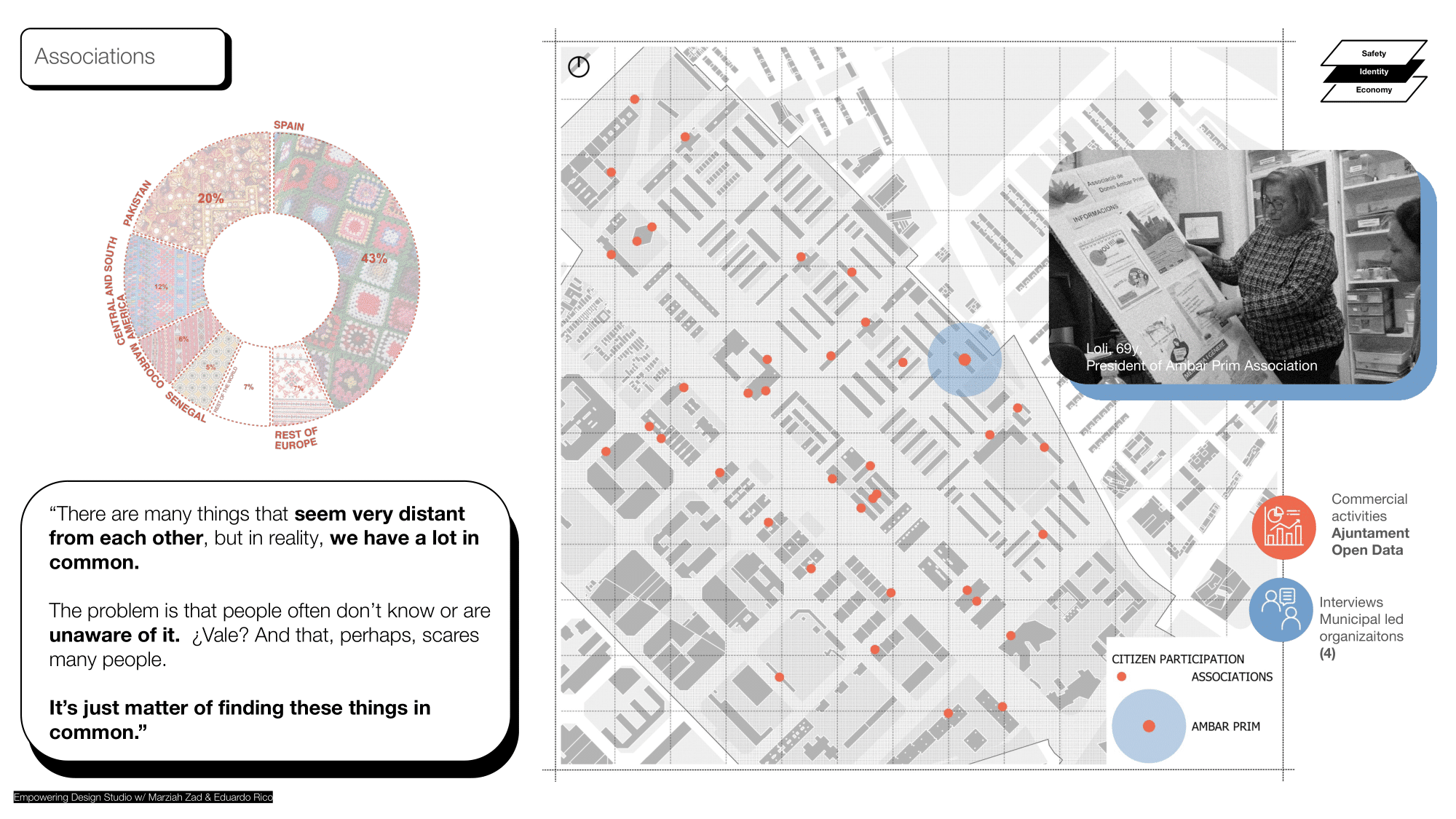

Besòs is shaped by multiple migrant identities.

Conclusion 3:

People of Besòs are suffering an expulsion.

The shift of land use due to 22@ creates a decline of working class jobs, affecting an already economically vulnerable group.

Conclusion 4:

The building typology of social housing with non-active ground floors cements insecurity lacking eyes on the street and exacerbates the economic decay.

Conclusion 5:

People of Besos are reclaiming the public space that has been systemically underserved.

Conclusion 6:

Ambar Prim is already organized. The limitations that they face to engage more people, could be covered by bringing their skills to a public space and linking the people with an element every culture has: textile

Site Analysis

Key Observations & Design Strategy

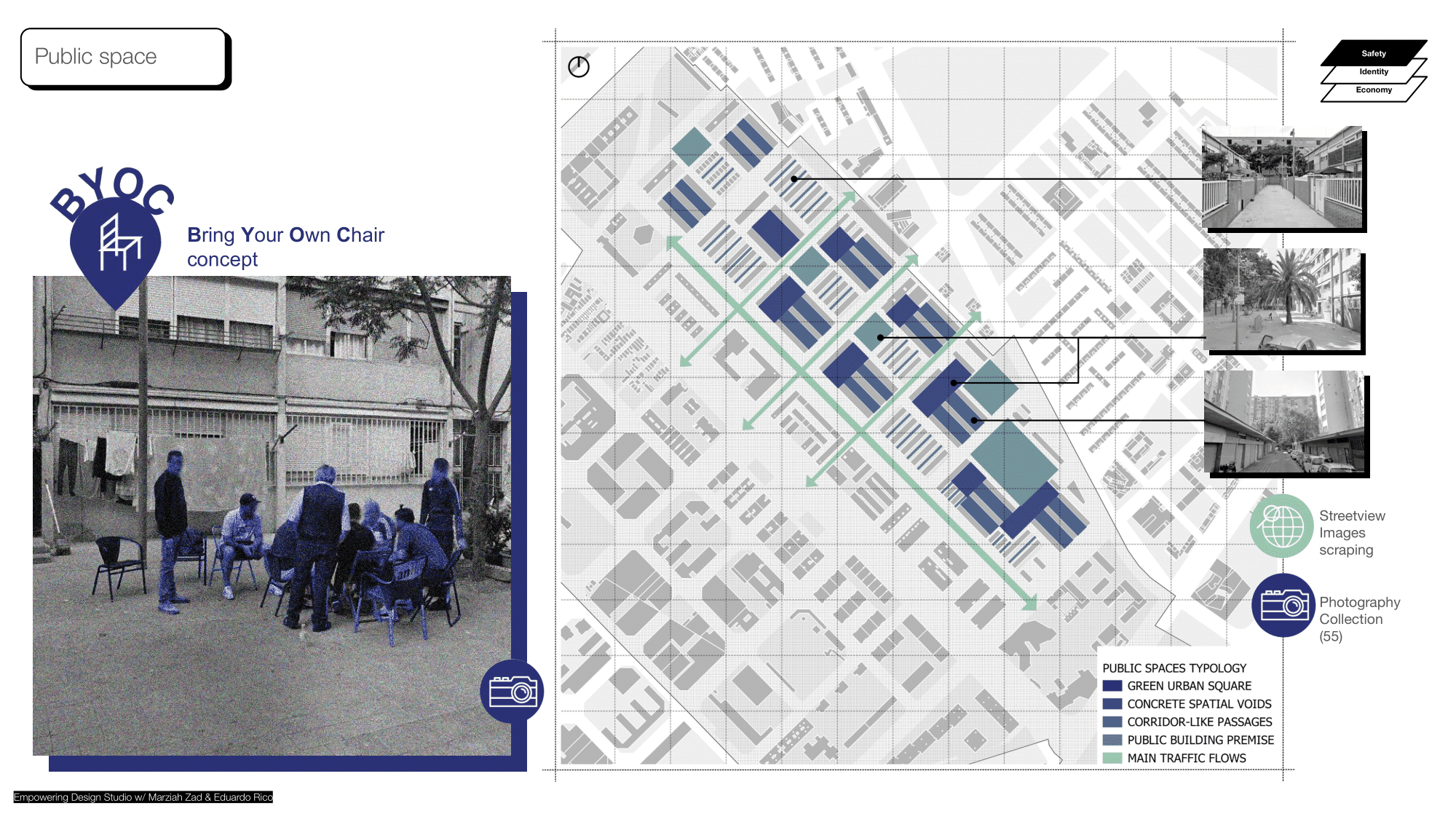

BYOC & Insufficient Infrastructure

The square currently lacks sufficient urban furniture, particularly seating. The shortage of benches has led to a phenomenon we describe as “Bring Your Own Culture” (BYOC)—where users adapt the space by bringing their own seating or improvising gathering spots. This highlights the need for additional infrastructure to support informal and self-organized activities.

Movement Patterns & Lighting

Real-time surveys reveal that lighting significantly influences user movement. People primarily navigate along the paths illuminated by existing light poles, indicating that spatial legibility and nighttime accessibility need to be improved. Strategically placed lighting and circulation pathways can enhance usability and encourage safer, more dynamic movement across the square.

Association & In-Between Spaces

The lack of seating in the central area, combined with movement patterns shaped by lighting conditions, results in a sense of in-betweenness—a large portion of the square remains underutilized. Additionally, the Ambar Prim association, located nearby, has minimal connection to the space. Strengthening these links through infrastructure and programmatic interventions can activate the central square and integrate it more effectively into the urban fabric.

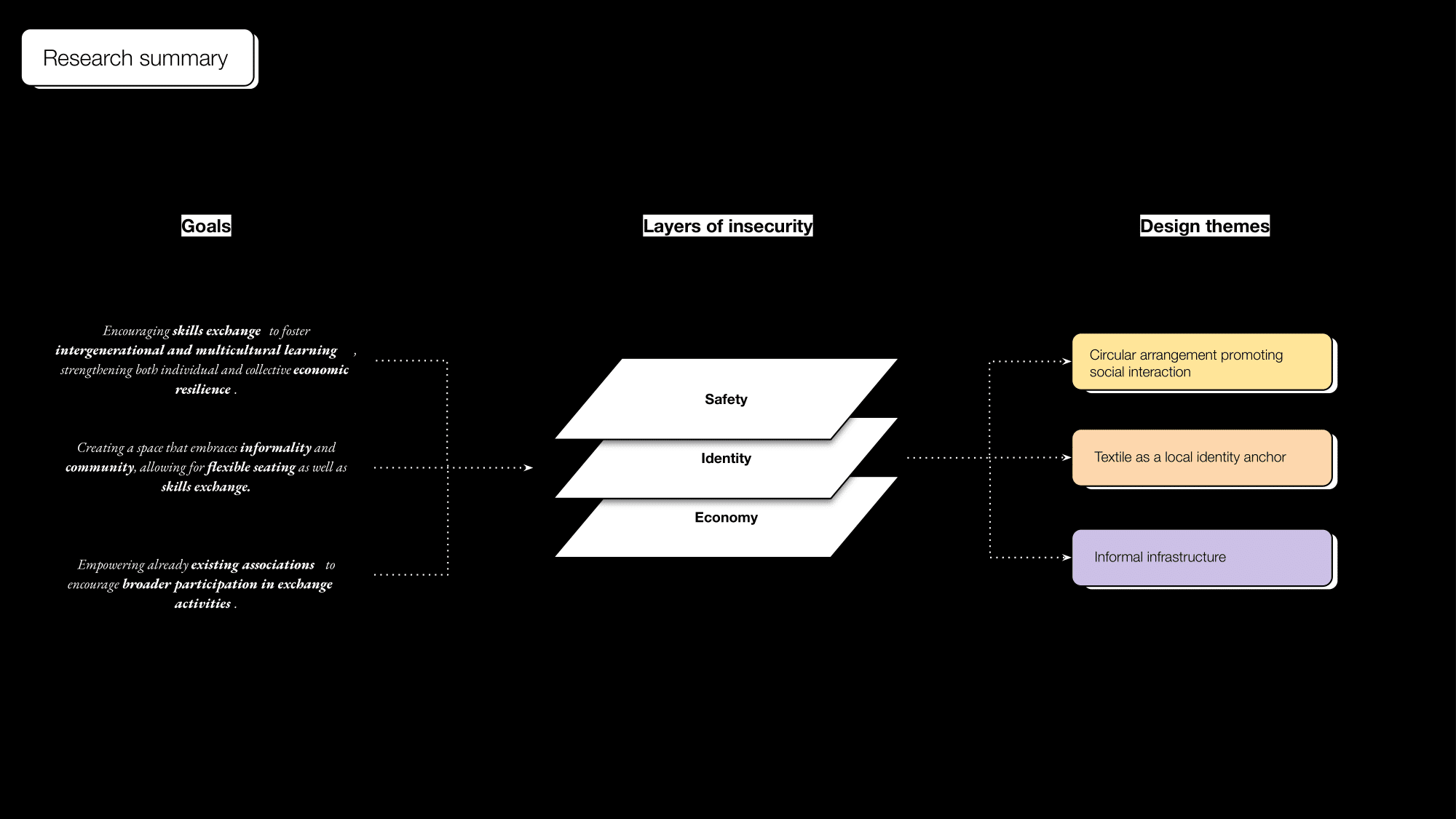

Research summary

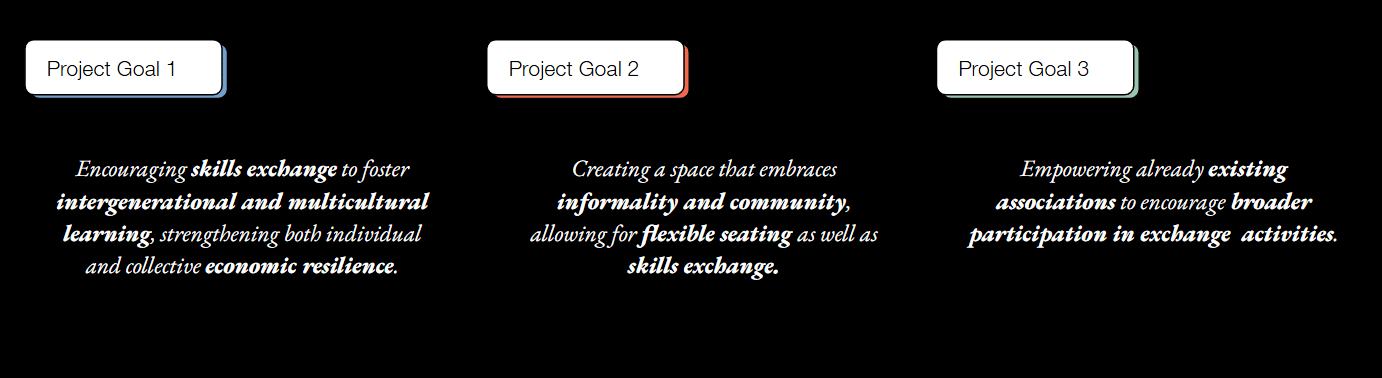

So far, were able to come up with conclusions that led us to project goals. In order to translate them to the language of design, we overlaid project goals with our understanding of insecurity issue and its multiple layers. The combination allowed us to distinguish three design themes for the next, design part of the process. The themes are following:

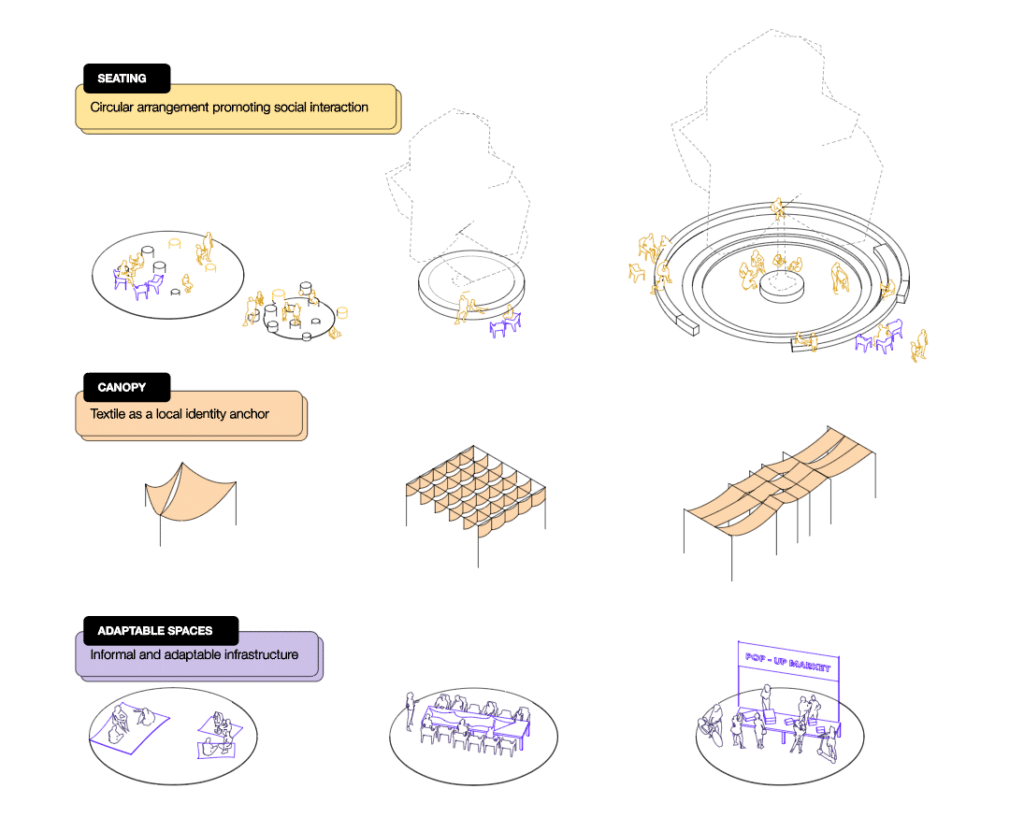

- Circular arrangement promoting social interaction

- Textile as a local identity anchor

- Informal infrastructure

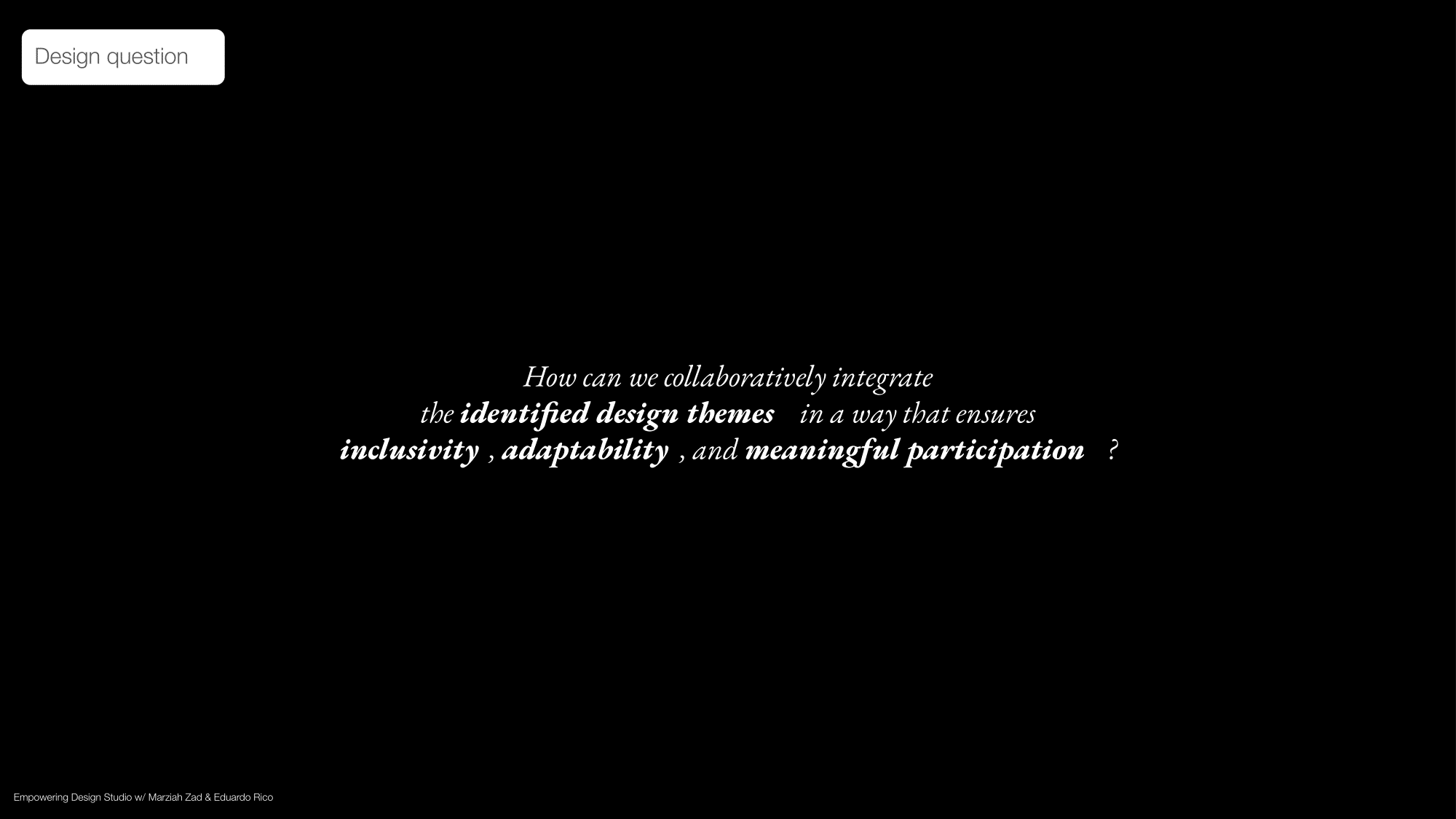

Having the reserch done, we came up with a design question that concisely inputs our research efforts into the final design.

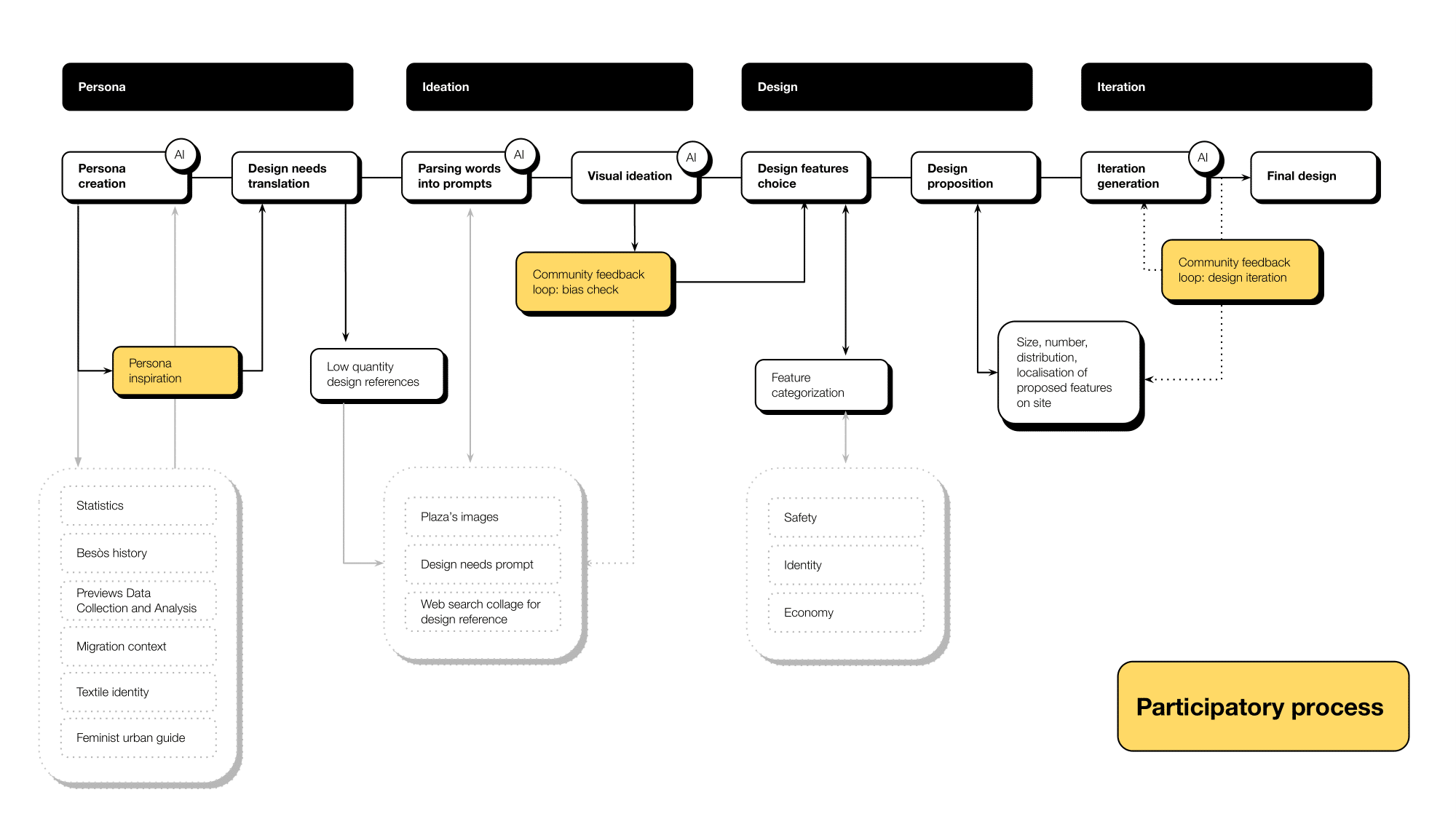

Participatory Design Methodology

The methodology combined three key elements: AI-generated insights, designer-led analysis and decision-making, and community consent.

- AI Contribution: AI was used to generate personas and design inspirations based on demographic, historical, and cultural data.

- Designer Analysis & Decisions: Designers critically assessed AI outputs, using their expertise to identify meaningful intersections, refine design elements, and ensure coherence.

- Community Consent & Validation: A bias-checking process was carried out to ensure inclusivity, and community input was sought to validate and refine design choices.

Consent is crucial because both AI and designers inherently carry biases—especially when creating representations of cultures and places we haven’t directly experienced.

- AI Bias: AI models are trained on existing datasets, which often reflect stereotypes and historical inequalities. This can lead to misrepresentations or oversimplifications of certain cultures.

- Designer Bias: As designers, our perspectives are shaped by our own experiences, cultural backgrounds, and the media we consume. When designing for places we haven’t visited, there’s a higher risk of unintentional bias or misinterpretation.

By incorporating community consent and validation, we ensure that the representations and design choices are more authentic, inclusive, and contextually accurate. This step helps challenge assumptions and refine the project to better reflect the people it aims to serve.

This hybrid approach ensured that the design process was data-informed, human-centered, and socially responsible.

To create a simulation of a participatory process, we generated 10 personas using AI. The approach we followed was:

- First, we provided the AI with statistics and demographic data from Besòs, including age, gender, and nationality.

- Next, we shared our summary of Besòs’ history and cycles of exclusion, along with the sources from which we obtained this information.

- We then provided our full midterm presentation, which included our analysis and the task we aimed to accomplish—simulating the participatory process.

- To enrich the personas, we asked the AI to consider each individual’s cultural and migration background based on their country’s history, migration waves, and trends.

- We instructed the AI to focus specifically on the slides in our presentation related to the textile industry.

- Finally, we provided an additional input: a Feminist Urban Guide, ensuring that the personas could express diverse needs and perspectives.

After multiple iterations in creating the personas, we arrived at something truly interesting—insights that could be translated into tangible design elements.

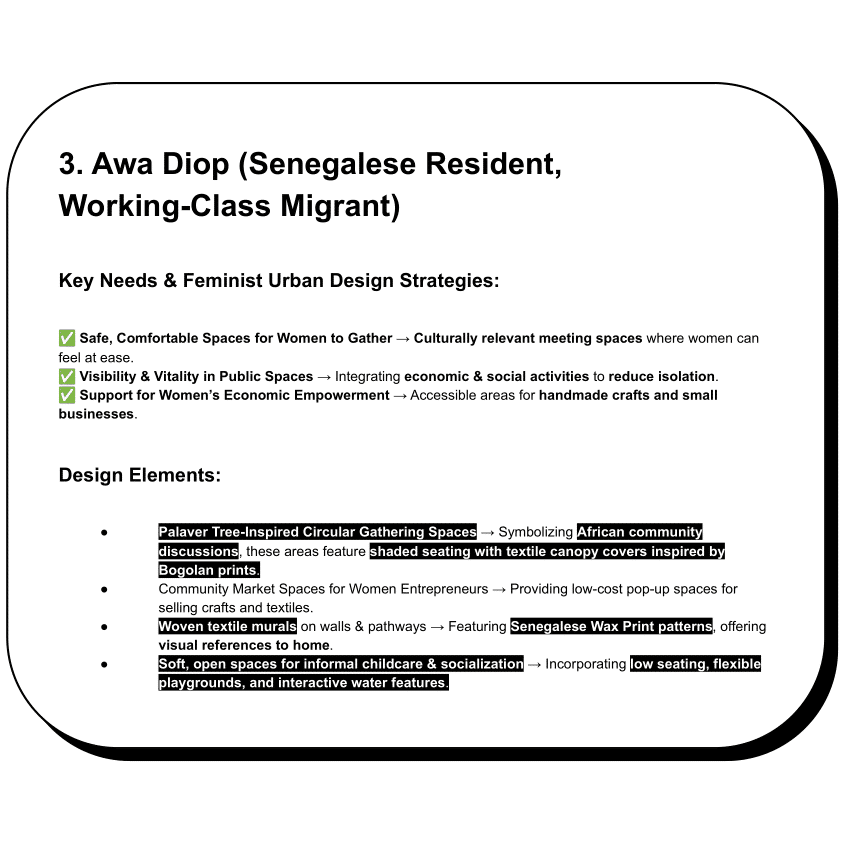

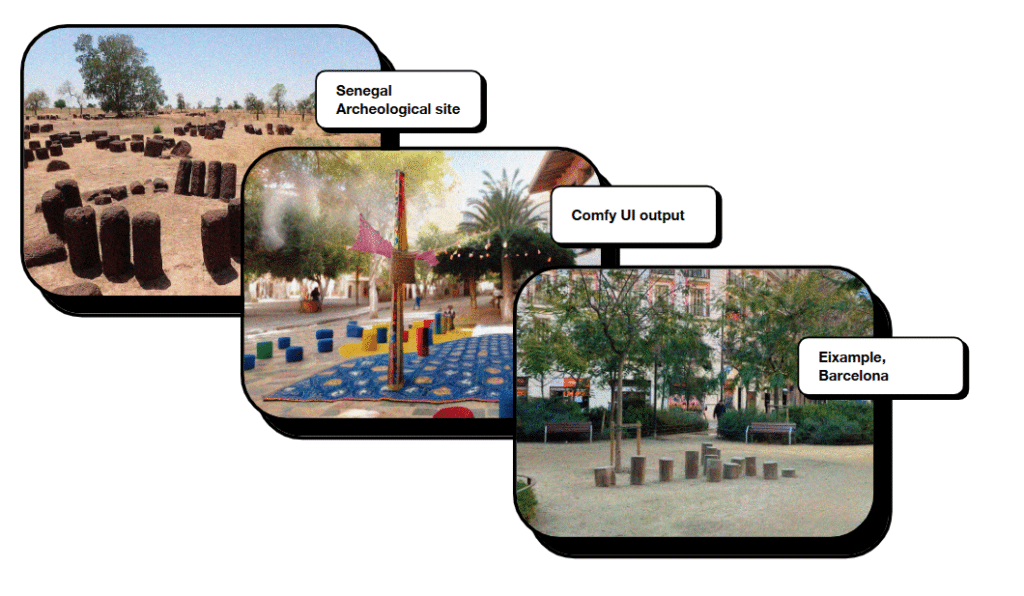

On the right, we can see an example of one such persona. This persona, representing someone from Senegal, inspired ideas like Palaver Tree-Inspired Circular Gathering Spaces, which played a significant role in our design process. Similarly, the seating arrangement used in African community discussions was another key element that highly influenced our approach.

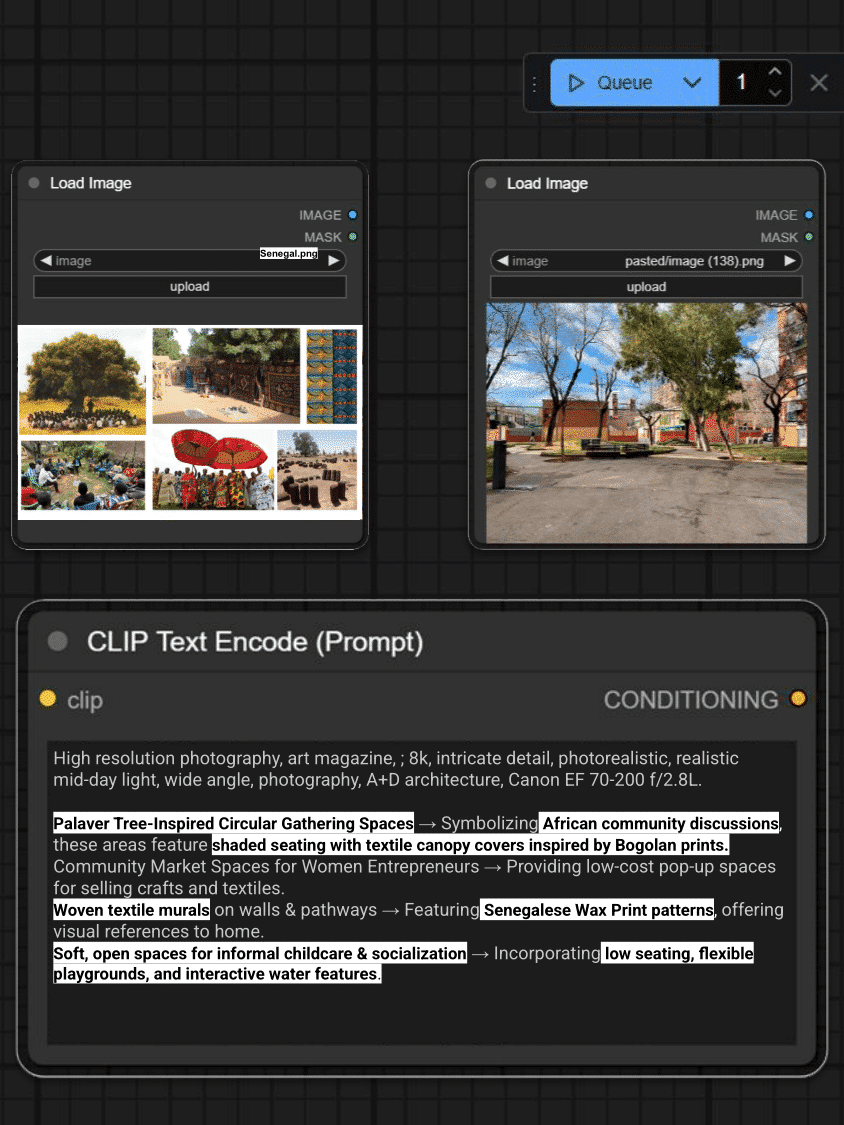

Since these elements are not widely represented on inspiration platforms like Google or Pinterest, we decided to create our own references. To do this, we used ComfyUI and generated visuals based on three key prompts:

- A collage incorporating the elements mentioned in the persona’s output.

- The text describing the design elements suggested by the persona.

- The site as the foundation of the image, from which we derived composition and depth.

This approach allowed us to visually translate abstract concepts into concrete design inspirations.

DESIGN:

DESIGN FEATURE CHOICE

To continue with the results shown on the right, a consent process had to be carried out to check for biases and stereotypes.

After this step, we needed to make decisions about which features to incorporate. To guide this, we applied our insecurities lenses:

- Security: We focused primarily on location, flexibility, and visual permeability to ensure safety and accessibility.

- Identity: Using our human analytical skills (rather than AI), we identified and combined elements from different cultures where meaningful intersections and connections could be found—such as the example below.

- Economiich played a significant role in our design process. Similarly, the seating arrangement used in African community discussions was another key element that highly influenced our approach.

DESIGN:

DESIGN FEATURE CHOICE

This project translates key design features identified during the participatory process into tangible spatial elements across three main categories:

Seating – Fixed seating areas providing comfortable gathering points.

Canopy – Shaded structures enhancing climate resilience and usability.

Adaptable Spaces – Flexible zones that accommodate different activities and seasonal events.

DESIGN:

DESIGN PROPOSITION

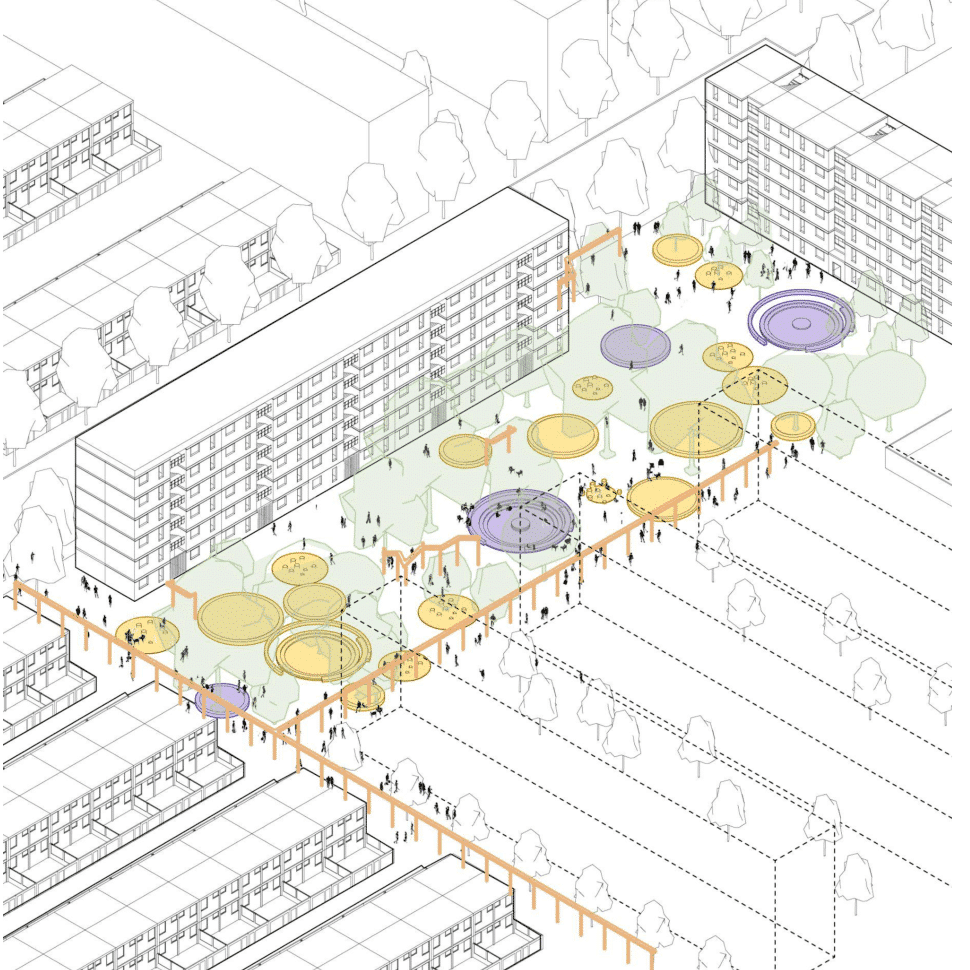

Parametric Design & Community Engagement

A parametric approach is central to this participatory design process, enabling real-time modifications based on community input. Through interactive tools such as sliders, community members and designers collaboratively explore different design variations. While key design variables are initially defined by designers, iterative community feedback helps refine and align the proposal. Designers critically assess the final iterations to ensure optimal spatial configurations for the square.

DESIGN:

FINAL DESIGN

The axonometric representation showcases a potential design outcome shaped by community engagement and spatial analysis. The design remains adaptable, responding to input and contextual needs. In this version:

- Yellow zones represent fixed seating areas.

- Violet zones indicate flexible spaces for dynamic interactions and seasonal events.

These elements are strategically positioned near the Ambar Prim association entrance and the central square to foster engagement and accessibility.

ITERATION VOL 2

PARTICIPATORY PROCESS II

The participatory second process part was dedicated to merging concrete design visualisation with imaginary layer of generative AI.

The 3d software render involved feature qualitites selection in a participatory way. The part where we employed ComfyUI pipeline allowed us for more creativity in terms of deisgning a canopy – element that would involve participation of plaza stakeholders and people who would manually create the woven, textile canopy. That brings in another level of participation – an incredibly tangible one.

The participatory input is crucial for every iteration of proposed design – the involved community would accept or negotiate design features and the final shape and look of the plaza. In the design output of our process we were able to harness generative AI to bring in more imaginative approach for the stakeholders, as well as a tool that lets designers iterate faster on designing with the community involved.

Project’s conclusion

Our project, Layers of Besòs, is not just about designing space—it’s about unfolding identities, revealing hidden narratives, and fostering a more inclusive urban experience. Through the research and design we were able to share our point of view on how today’s participatory process could look like thanks to a variety of new technology and data processing techniques. As cities worldwide face similar challenges of exclusion and displacement, this project stands as a testament to the power of participatory design and data and AI-driven insights in shaping a more equitable future.